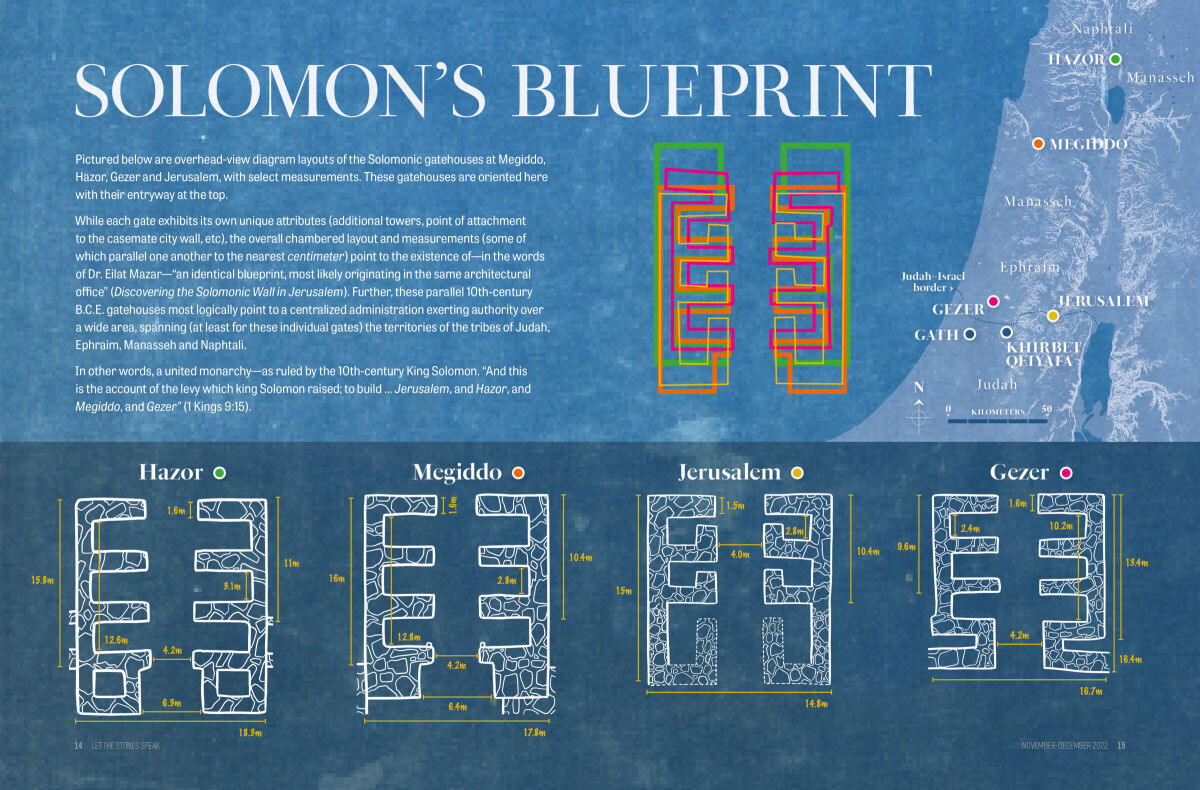

In his detailed analyses of the Gezer, Megiddo and Hazor gatehouses (published in his 1986 article “The Design of the Royal Gates at Megiddo, Hazor and Gezer”), surveyor David Milson deduced that besides the parallel nature of these structures, the engineers who built them used as their standard the Egyptian royal cubit, or “long cubit” (0.524/0.525 meters).

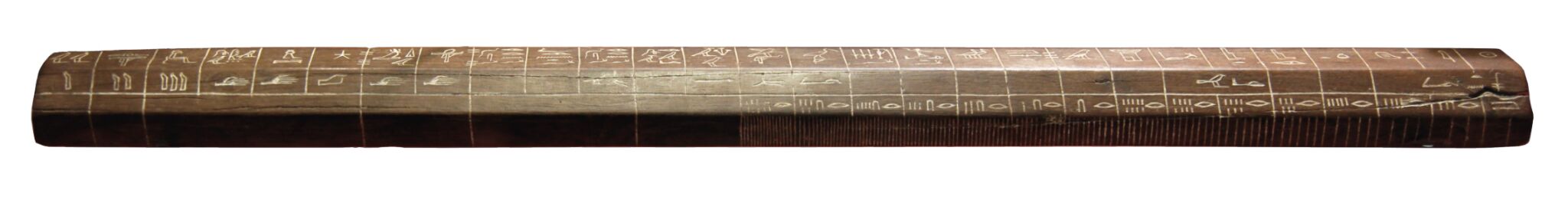

Milson determined this by comparing the width of the entry passages of all three gates. These all measured precisely 4.2 meters. As it turns out, this is exactly eight lengths of an Egyptian royal cubit, which is 0.525 meters. We know the exact length of a long cubit thanks to several archaeological discoveries. The “Ruler of Maya,” an inscribed cubit rod discovered in Saqqara, Memphis, in the early 1800s, is particularly notable. This measuring rod, which dates to Egypt’s 18th Dynasty (14th century b.c.e.), is currently archived at the Louvre Museum in Paris (Louvre N1538). The fact that this Egyptian measure dates to the 18th Dynasty is interesting given that this is the Egyptian dynasty best fitting with the biblical chronology for the Exodus.

Numerous references to cubit measurements are found throughout the Bible. There are two primary cubits: one “long” and one “short.” The “short cubit” is generally explained as the distance from elbow to tip of the middle finger, otherwise defined as six “hands.” As shown by archaeological discoveries, this standardized measurement is 0.44/0.45 meters. The “long cubit,” or Egyptian royal cubit, is defined as a short cubit “plus a hand”—or, seven hands (standardized as 0.524/0.525 meters).

There are several interesting biblical references to such “short” and “long” cubits. The “short” cubit was evidently used primarily during later monarchical periods. A case in point is Hezekiah’s Tunnel (eighth century b.c.e.): The Siloam inscription states that the tunnel length was cut to “1,200 cubits.” Dividing the known length of the tunnel (533.3 meters) by 1,200, we have 0.44—the exact measure of the short cubit. Further, even the size of the Siloam Inscription sign itself (0.66 meters) and other contemporary burial inscriptions (1.32 meters) are precise multiples of this short, 0.44-meter cubit measure.

2 Chronicles 3:3—a late passage traditionally ascribed to the hand of Ezra during the fifth century b.c.e.—describes Solomon’s temple being constructed with “cubits after the ancient measure” (translated as “the first measure” in the King James Version). Ezra is evidently referring to long cubits, as opposed to the standard “short” measure at the time of writing. Likewise, the book of Ezekiel, written in the sixth century b.c.e., clearly denotes that a future temple would be built after the long-cubit measuring reed—“of a cubit and a hand-breadth each,” or the seven-hands-long royal cubit, paralleling that used for Solomon’s temple (Ezekiel 40:5; see also 43:13—“the cubit is a cubit and a handbreadth”).

Clearly, the examples in 2 Chronicles 3 and Ezekiel show that these cubit measures were a departure from the norm at the time of writing, hence the necessary specification. The same is true on the opposite end of the time spectrum, in early Israel. Deuteronomy 3, for example, records the enormous size of the giant Og’s bed. Verse 11 says “nine cubits was the length thereof, and four cubits the breadth of it, after the cubit of a man.” This must have been the short cubit, the length of a man’s arm from elbow to fingertip—a measurement that could be more readily and quickly used for measuring mundane items. It is interesting to note, on the other hand, that in the detailed measurements given for the tabernacle (Exodus 25-31) and later Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 6-7), no specification is given in these earlier accounts for the cubit length (in contrast to the later texts). This must have been because the long cubit was the standard already in use at that time.

Milson’s discovery, then, that the Solomonic gates were built using the “long” cubit, is a remarkable fit with the biblical account. It is evident that this was the very measure used by Solomon during his reign—an “ancient measure” that in its own way attests to the antiquity of these structures.