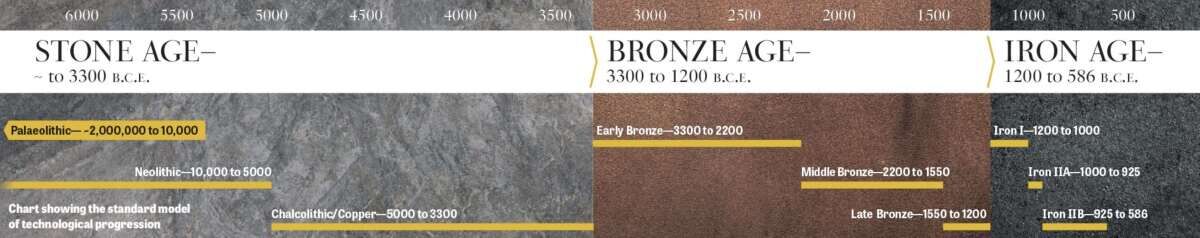

The first three periods of ancient history are divided into unique classifications: Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age. These three archaeological periods are named after the predominant metal used for tools and weapons at that time. But as we explained in our article “Understanding the Archaeological Timescale,” this method of dating, established by Danish archaeologist Christian Jurgensen Thomsen in the early 19th century, isn’t perfect (see “Understanding the Archaeological Timescale” for more information).

We know that the Late Bronze Age (1500–1200 b.c.e.) ushered in the Iron Age i (1200–1000 b.c.e.). Based off Thomsen’s model, one would expect a rise in the use of iron in Iron Age i. However, this was not the case in Israel. According to Hebrew University metallurgy specialist Prof. Naama Yahalom-Mack, iron “was only present in small quantities in the form of prestige items, while bronze continued to be the most prevalent metal for tools and weapons” (“Production Autonomy to Centralization: The Iron I to Iron IIA Transition From a Metallurgical Perspective”).

Iron was used in the Iron Age i period in Israel, but it had more of a decorative function. Even into the Iron Age, bronze had more practical, utilitarian uses and was cheaper to produce, and was, therefore, more widespread. Iron didn’t overtake bronze until Iron Age iia, which began in 1000 b.c.e.

Was there a reason for the timing of this transition from bronze to iron?

Studying the transition from bronze to iron in Israel provides evidence of a strong, authoritative central government beginning around 1000 b.c.e. This was the time period of the united monarchy, mainly kings David and Solomon. Were these two kings responsible for bringing Israel into the more sophisticated Iron Age?

We see evidence of this shift from bronze to iron in the Iron iia period at five sites across Israel: Hazor, Megiddo, Beth Shemesh, Khirbet Qeiyafa and Rehov.

A Survey of Sites

The archaeology of these sites shows that not only is there a transition from the use of bronze to iron in the Iron iia, but the location in which the metal-working took place changes. “Since bronze-working was practiced in domestic contexts during the second millennium b.c.e., we have suggested that the shift to iron production, associated with public architecture, indicates the involvement of a central administration in the transition from bronze to iron production at the site,” wrote Professor Yahalom-Mack (emphasis added throughout).

Generally, bronze was worked in homes; iron, however, was worked in public buildings, which were essentially small metalwork factories. The common people worked bronze as a domestic activity, but in the Iron iia, iron-working was moved to the center of the Israelite city and economy. Some craftsmen seem to have worked iron where they had previously worked bronze, but they were likely “‘attached craftsmen’ under the auspices of the central administration,” wrote Yahalom-Mack.

In 2015, Yahalom-Mack and Dr. Adi Eliyahu-Behar described “attached craftsmen” as “formerly independent metalsmiths who were now attached to the ruling elite at the same time that they shifted from mainly bronze to mainly iron production” (“The Transition From Bronze to Iron in Canaan”). These were individuals who were now working on behalf of the government of Israel.

Let’s first consider Hazor. The Bible describes this as a major city in Israel during the united monarchy. 1 Kings 9:15 says it was one of the cities Solomon fortified. At Tel Hazor, not far from the city’s legendary six-chambered gatehouse, esteemed archaeologist Prof. Amnon Ben-Tor’s team discovered several slag cakes under the floor of Building 9127, indicating iron smelting took place at this building. The stratum in which the structure was found has been dated to the Iron Age iia (early 10th century b.c.e.)

Under this layer, were signs that the site had once been used for bronze-working. “[T]his is significant, as it possibly indicates an official decision to replace bronze-working with iron production,” wrote Yahalom-Mack.

Megiddo was also fortified by King Solomon (1 Kings 9:15) and yields similar finds to Hazor. The southeastern edge of the mound at Tel Megiddo had remains of an iron production facility. The corner of a pillared public building, which dates to the Iron iia, was filled with dark sediment that contained iron hammer scales (flecks of iron debris from the forging process). At another location just east of the pillared building, excavators discovered iron prills (hardened drops of molten iron), hammerscales and over 30 iron slag cakes. This iron production site was proximate to another major public building at Megiddo called Building 1723.

Beth Shemesh was another important site during the reigns of David and Solomon. It was a border town with the Philistines, who, according to 1 Samuel 13:19-22, dominated ironworks during the reign of Saul (circa 1050–1011 b.c.e.).

This city features several layers of iron-working next to public structures dating to the Iron iia. The excavation directors at Beth Shemesh, professors Shlomo Bunimovitz and Zvi Lederman, were among the first to postulate that there was a connection between iron production and an Iron iia central administration: “The finds at Beth-Shemesh hint, therefore, that social and political centralization in Judah during the late 10th and ninth centuries b.c.e. was accompanied by appropriation and control of iron technology, presumably due to its growing economic importance” (“Iron Age Iron: From Invention to Innovation,” 2012).

Khirbet Qeiyafa is interesting because it is a single-layer fortress that carbon-dating of olive pits has shown was used from 1020 to 980 b.c.e., squarely within the reigns of David and Solomon.

Under the direction of Hebrew University professor Yosef Garfinkel, archaeologists found a hearth in Area A of the site in a corner of a large public building. The hearth was filled with dark magnetic sediment and iron chips. This discovery indicates that forging and iron production were performed at the site at the time of David. Sixteen of the 26 tools or weapons discovered at the site were made of iron. “This is an unusually high percentage of iron objects for an Iron i site,” wrote Yahalom-Mack. Both bronze and iron were worked at Khirbet Qeiyafa.

At Tel Rehov, iron slag cakes and debris were found alongside bronze spatter and prills in Stratum v, which is dated to the Iron iia. The discovery of cultic paraphernalia (a bamah and a few matzevot) indicated that this location later functioned as an open-air sanctuary. Though the sanctuary itself can only be dated with certainty back to Stratum iv (end of the 10th century b.c.e), the continuity of activity in surrounding buildings suggests it dates back further. Therefore, cultic activities and iron production presumably were occurring at the site at the same time.

These are not the only sites with significant iron-working remains. Yahalom-Mack also analyzed discoveries at Tel Abel Beth-Maacah, Tel Hammeh and Tel es-Safi/Gath.

Metal-working was a crucial part of ancient economies. It’s apparent that in the Bronze Age and Iron i, the government of Israel had less control over economic factors; for much of this period, there was no centralized government authority. But during the reigns of David and Solomon, this changed. Both the Bible and archaeology indicate that the government played a larger role in Israel’s economy and industry in the time of David. As part of this trend, it is logical that David and Solomon would have moved metal-working to city centers under the auspices of nearby government structures.

The consistency and uniformity with which this occurred at the sites surveyed above suggests that this was a deliberate decision from a central authority. “The presence of iron production venues associated with major public architecture in the urban centers that are characterized by town planning and fortifications in the Iron iia allude to close interaction between the iron industry and the central authority,” wrote Yahalom-Mack. “The introduction of a new metal must have been of great social significance, and thus advantageous for the ruling elites, strengthening, along with building activities and other actions, their legitimacy to rule.”

The Push Toward Iron

Iron was not superior to bronze as it was introduced on a larger scale in the Iron iia. Based on early Iron iia discoveries, ironworkers had not yet learned how to regulate carbon and quench their products, the process which transforms iron into steel. Without this process, iron and bronze are of almost equal hardness. Additionally, iron was more difficult to forge than bronze because it could not be melted in a crucible and poured into molds; it had to be shaped with a hammer. This is accurately described in the Bible: “The smith maketh an axe, And worketh in the coals, and fashioneth it with hammers, And worketh it with his strong arm …” (Isaiah 44:12). Also, copper (the primary ingredient of bronze) would have been in ample supply from the mines of Timna and Faynan (see “Copper Mines of the United Monarchy” for more information).

Why then did a central administration in Israel push the adoption of iron?

Archaeology has yet to answer this question confidently. “[T]he preference for iron over bronze during the Iron iia appeared to be related more to symbolic considerations, as well as economic factors,” Yahalom-Mack concluded.

Unfortunately, the most important economic factor of iron production—the source of the iron—is yet to be discovered. Iron is generally much more accessible than bronze because it can be “quarried superficially i.e. does not require expansive mining operations,” wrote Yahalom-Mack. However, not all iron sources produce iron of high enough quality to be worked. Because of this, Yahalom-Mack concluded, “It is thus more likely that there was a limited amount of quality iron ore sources, which would have been sought by the authorities in each political unit.” Perhaps the location of these sources was a major reason iron was so strongly endorsed. Iron could have been mined in the heartland whereas bronze came from mines hundreds of miles away in barren deserts occupied with warlike nomads.

Yahalom-Mack also cited “symbolic considerations.” Iron had existed for centuries in the Near East, though not in abundance. When iron is collected as an ore from the Earth’s crust, it must be forged to purge its non-metal adulterants. There is one source of iron that is almost pure: meteors.

Meteoric iron is already in its solid metal state. However, it is rare. Because of its rarity, meteoric iron was a prestigious metal in the Bronze Age and was only used for ceremonial items (like Tutankhamen’s knife or even, possibly, Canaanite chariots; see “Iron Chariots: A Biblical Impossibility?”). This prestige long associated with iron may have stirred officials and smiths to seek its mastery. Regardless of the exact reason for the change, we do know that around the Iron iia period, iron went from a decorative metal to a functional one while bronze went from a functional metal to a decorative one.

Silver Regulation

Iron is not the only metal that seems to have been controlled or endorsed by a central administration. In the transition between the Iron i to the Iron iia, silver also became far more common in Israel.

Scientific studies show that silver from the Iron iia is of significantly higher quality than pre-Iron iia iron. “This, among other evidence, suggests that silver quality became regulated during the Iron iia; regulation that was most likely initiated and controlled by the same central administrations that appropriated the use of iron for the production of utilitarian objects,” wrote Yahalom-Mack.

Silver from the Iron iia can also be linked to the Phoenicians’ trading exploits in the Western Mediterranean (for more on these trading efforts, read “Seeking Solomon: United Monarchy on the High Seas”). The Bible also records an important alliance between Israel and Phoenicia in the times of David and Solomon, which included trading silver.

Our Historical Text

It is noteworthy that these trends and discoveries occurred in a period that is described in detail in the biblical text, and the biblical descriptions match beautifully with the archaeology. The Bible describes a strong, authoritative government rising in Israel exactly when archaeologists note the centralization of metallurgical technological progress. The Bible says there was a sovereign government involved in the economy, and archaeological data from Hazor to Khirbet Qeiyafa corroborates that claim.

Iron is mentioned several times in connection with David and Solomon. After conquering the capital of Ammon, David “brought forth the people who were in it, and set them to labor with saws and iron picks and axes” (1 Chronicles 20:3; Revised Standard Version). 1 Kings 6:7 says, “For the house [Solomon’s temple], when it was in building, was built of stone made ready at the quarry; and there was neither hammer nor axe nor any tool of iron heard in the house, while it was in building.” The Bible clearly records that, in the early Iron iia, iron was the preferred material for tools.

1 Chronicles 29 describes an offering made by the people of Israel for the construction of the temple. Verse 7 says that 18,000 talents of bronze were donated, and 100,000 talents of iron. A talent is believed to have weighed around 34 kilograms (based on Exodus 38:26-28), suggesting this was roughly 3.4 million kilograms of iron. The Israelites must have found plenty of iron mines. Though the mines are undiscovered, the bounty of iron artifacts at sites from the Solomonic period matches this well. In 1 Chronicles 22:14-16, David records he had collected both bronze and iron “without weight, for it is in abundance.”

2 Chronicles 2 also records Solomon requesting craftsmen and artisans from Phoenicia who were experts in skills including iron-working. Hiram sent a man “skilful to work in gold, and in silver, in brass [bronze], in iron …” (verse 13). 1 Chronicles 22:3 records that “David prepared iron in abundance for the nails for the doors of the gates, and for the couplings ….” The decorative features of the temple like the lavers or the molten sea were made of bronze. Archaeology likewise shows that at this time bronze was becoming a decorative metal while iron was becoming a utilitarian metal for items such as nails or couplings.

Although the Bible does not specifically mention David and Solomon endorsing iron above bronze as the national utilitarian metal, the archaeology of the transition from iron to bronze does shed light on their kingdom. The Bible portrays it as having a powerful central government with a hands-on involvement in economic and commercial affairs. Based on the discoveries of iron and bronze at sites scattered around Israel, archaeologists have concluded there had to be a central authority in Israel during the transition from the Iron i to the Iron iia—the time of David and Solomon.