The Hebrew Bible is a book primarily about Israel. But it also contains many important historical records of other civilizations as they came into contact with Israel. Some, like Egypt and Assyria, are world famous and left behind great wonders. Others are more obscurely referenced in the biblical account—in some cases, containing the scarcest details about them save their names. But it doesn’t make their history and heritage any less real—or any less interesting.

Such is the case for two enigmatic peoples: Meshech and Tubal. These two nations repeatedly pop up together in the biblical narrative. The biblical authors recorded very few details about them. But comparisons with the archaeological record and other ancient sources give a unique insight into these two polities.

What the Bible Says

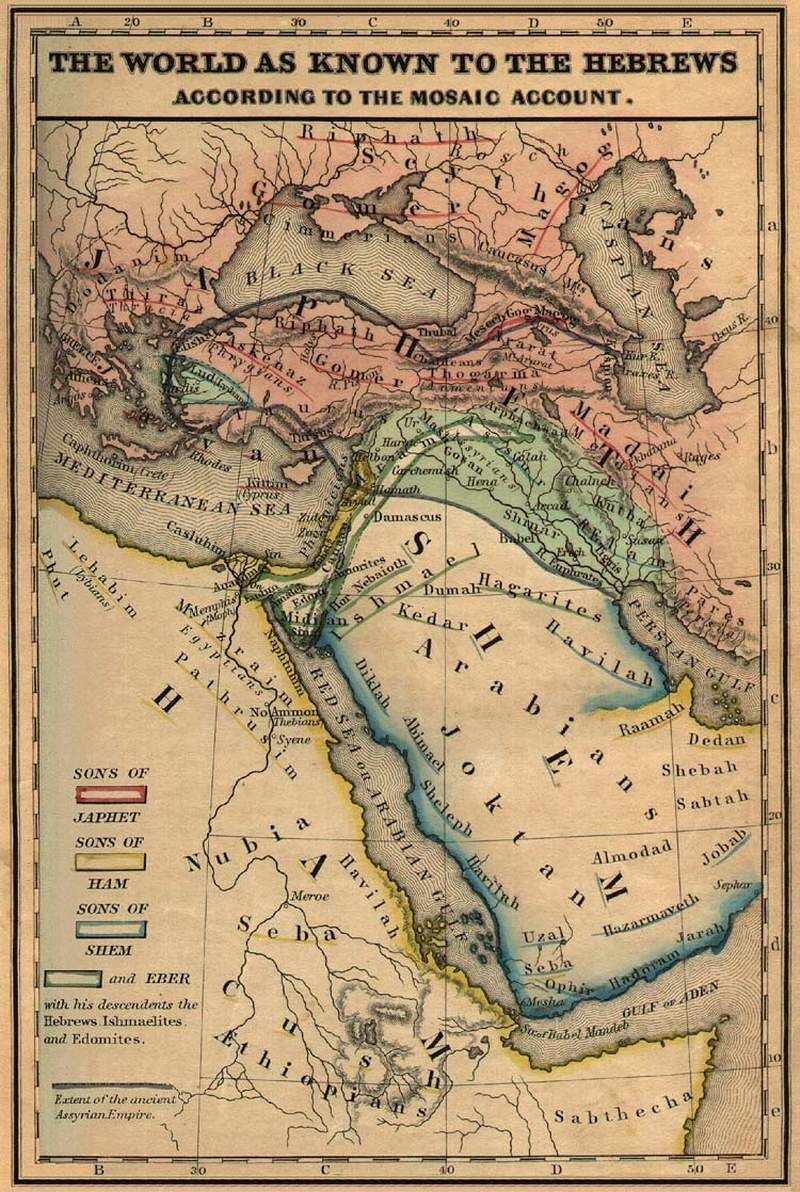

We get our first introduction to Meshech and Tubal in the famed “Table of the Nations” of Genesis 10. Verse 1 introduces the setting: Noah and his three sons—Shem, Ham and Japheth—repopulating Earth with their descendants after the worldwide flood. Verse 2 reads: “The sons of Japheth: Gomer, and Magog, and Madai, and Javan, and Tubal, and Meshech, and Tiras.” 1 Chronicles 1:5 records the same list.

Genesis 10 lists Meshech and Tubal as descendants of Japheth. Shem was the patriarch of the Israelites, as well as other “Semitic” peoples like the Assyrians and Arameans (Genesis 10:22; 11:10-26). Ham’s descendants included the Kushites (sub-Saharan Africans), the Egyptians (under the name Mizraim) and the Canaanites (Genesis 10:6)—many of whom are located to Israel’s south. Japheth, in contrast, is the patriarch of various peoples to Israel’s north. Listed among his descendants is Javan, which to this day is the Hebrew name for Greece. The first-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus noted Javan’s connection to Ionia—the Greek settlements of Anatolia. Genesis 10:2 also lists Madai, the Hebrew word for the Medes. The Medes inhabited northwestern Iran. Logically, the location of the dispersal and descendants of Meshech and Tubal should be in the same direction.

The remainder of the biblical references to Meshech and Tubal are in the book of Ezekiel, a prophet on the scene during the first half of the sixth century b.c.e. Ezekiel 27:13 lists Meshech and Tubal as well as Javan among the clientele of the great trade center Tyre. Specifically, Ezekiel states Meshech and Tubal trading extensively in slaves. Ezekiel 32, meanwhile, lists Meshech and Tubal among a list of aggressive nations cursed by God: “There is Meshech, Tubal, and all her multitude; her graves are round about them; all of them uncircumcised, slain by the sword; because they caused their terror in the land of the living” (verse 26). A similar description is given to Assyria, another warlike people, in verses 22 and 23.

By far the most extensive record of Meshech and Tubal, however, is in Ezekiel 38. The passage records a lengthy prophecy and divine curse issued against these two entities: “And the word of the Lord came unto me, saying: ‘Son of man, set thy face toward Gog, of the land of Magog, the chief prince of Meshech and Tubal, and prophesy against him, and say: Thus saith the Lord God: Behold, I am against thee, O Gog, chief prince of Meshech and Tubal; and I will turn thee about, and put hooks into thy jaws, and I will bring thee forth, and all thine army, horses and horsemen, all of them clothed most gorgeously, a great company with buckler and shield, all of them handling the swords: Persia, Cush, and Put with them, all of them with shield and helmet; Gomer, and all his bands; the house of Togarmah in the uttermost part of the north, and all his bands; even many peoples with thee” (verses 1-6).

Verse 15 confirms Meshech and Tubal’s location as “the uttermost parts of the north.” Verse 15 also states the peoples’ military heavily depends on cavalry and features a notable “princely” ruler.

The chief characteristic of Meshech and Tubal is their militarism. In this case, the people have such a warlike disposition that they receive condemnation from God Himself. (Notice also Meshech and Tubal are put in the company of other descendants of Japheth, like Magog and Gomer.)

Does history have anything to say about such a people?

Introducing Meshech

Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews lists the locations where many Jews of the first century c.e. believed Meshech and Tubal settled. After describing the settlements of the Greeks and Medes, Josephus writes of a patriarch named “Theobel,” or Tubal, who “founded the Theobelians.” After this, Josephus introduces a people called Meschenians, founded by Meschos,” or Meshech. Josephus states the Meschenians “are to-day called Cappadocians, but a clear trace of their ancient designation survives; for they still have a city of the name of Mazaca, indicating to the expert that such was formerly the name of the whole race” (1.6.1).

Cappadocia refers to southeastern Turkey, near the headwaters of the Euphrates River. Geographically, on a west-east axis, Cappadocia is almost halfway between the Greek settlements in eastern Anatolia and the land of the Medes. Mazaca, for its part, still survives as a city in central Turkey; the area surrounding it has been an important settlement since Hittite times. By the time of the Achaemenid Empire, Mazaca was important enough to be the headquarters of a satrapy. In the first century c.e., the Romans made it capital of the Cappadocian province. Apart from Josephus’s testimony, there is sparse evidence linking Mazaca specifically with Meshech. However, it was not uncommon for ancient peoples to be named in relation to their capital city.

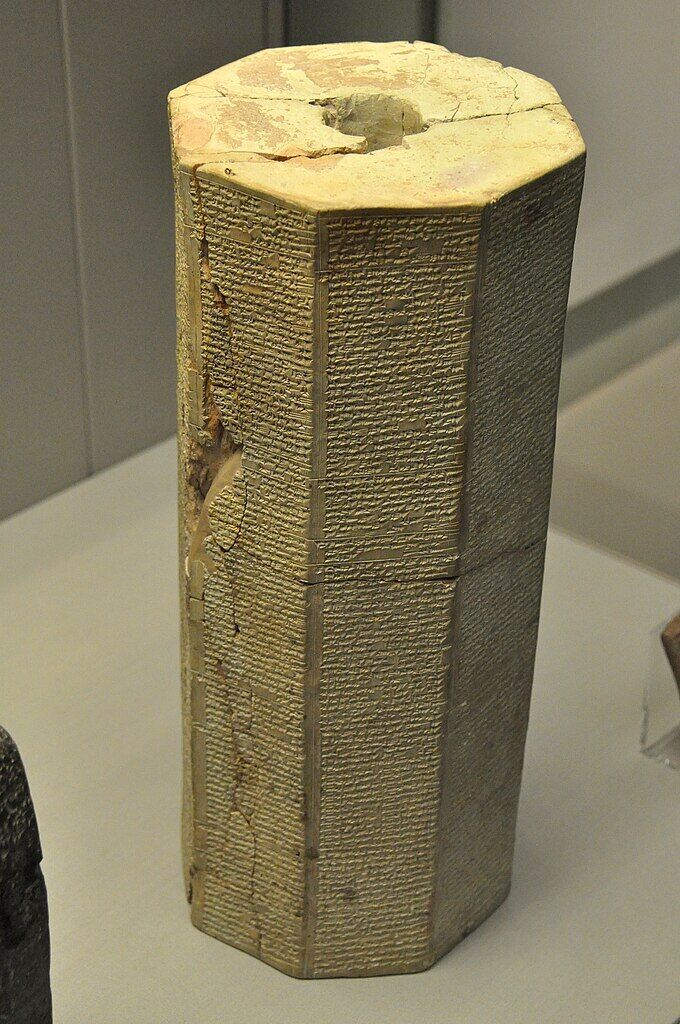

Such is the testimony from the first century c.e. But can archaeology bring us back any closer to the time period of the Hebrew Bible? Mesopotamian records do in fact confirm this region of Turkey to be home to a mysterious people known as the Mushki. Specifically, archaeology reveals them to be a perennial opponent of Assyria.

Our earliest reference comes from the chronicles of Assyria’s King Tiglath-Pileser i (1114–1076 b.c.e.). He recorded the following:

In my accession year, 20,000 Mushki and their five kings, who had held the lands Alzi and Purulumzi for 50 years, who bore tributes and tithe for the god Aššur, my lord, I put my chariotry and army in readiness [and], not waiting for my rear guard, I traversed the rough terrain of Mount Kāšiāru. I fought with their 20,000 men-at-arms and five kings in the land Katmuḫi. I brought about their defeat.

Alzi and Purulumzi are in northern Mesopotamia. Kadmuhi is to the east, toward Anatolia. This account puts the Mushki on the scene in this area right around the time that the Hittite Empire, the main power in Turkey for centuries, was collapsing. Dr. Renaat Meesters, an expert on this period, suspects the Mushki were among the outside peoples taking advantage of the Hittites’ collapse by moving into the area.

Prince of Meshech

Another notable reference to the Mushki comes centuries later, during the reign of Assyria’s King Sargon ii—a little more than a century prior to the references to Meshech in Ezekiel. Sargon ii (722–705 b.c.e.) is mentioned by name in Isaiah 20:1, and Assyrian records show him as the king responsible for deporting the northern tribes of Israel out of the Holy Land, as recorded in 2 Kings 17.

Sargon’s Assyria was a powerful empire stretching over much of the Middle East. But he couldn’t conquer everything. One territory that stayed independent was that of the Mushki, who kept themselves afloat under the leadership of a notable king.

In 717 b.c.e., Sargon was having issues retaining loyalty among his vassal states. Carchemish, an important city on the Euphrates River, was rebelling against Assyrian rule. But Carchemish’s king, Pisiri, had a problem: His small city-state was in no position to rebel against the mighty Assyrian Empire and needed a foreign backer. He found one in the Mushki.

Sargon wrote in his annals: “In my fifth regnal year, Pisiri (of) the city Carchemish sinned against the treaty (sworn) by the great gods and repeatedly sent (messages) hostile to Assyria to Mita, [k]ing of the land Mushku.”

Four hundred years after Tiglath-Pileser i wrote his annals, Mushki society had evidently coalesced. The Mushki were no longer ruled by a confederacy of kings. There was one overarching king, who was evidently a powerful enough king for Carchemish to see the Mushki as a reliable ally.

Circumstances didn’t favor Pisiri. Sargon continued:

I raised my hand(s) (in supplication) to the god Asshur, my lord, and brought him, together with his family, out in bondage. I then carried off as booty gold (and) silver, (along) with the property of his palace and the guilty people of the city Carchemish who (had sided) with him, (along) with their possessions. I brought (them) to Assyria. I conscripted 50 chariots, 200 cavalry (and) 3,000 foot soldiers from among them and added (them) to my royal (military) contingent. I settled people of Assyria in the city Carchemish and imposed the yoke of the god Asshur, my lord, upon them.

Carchemish fell. But Sargon made no record of attacking Mita and the Mushki heartland itself—an indication that Mita was too formidable of a threat. Sargon in his annals wrote that Mita “had not made his submission to (any of) the kings who lived before me,” suggesting both that Mita was too strong for Assyria to conquer and that he ruled during the reigns of multiple Assyrian kings.

Several bouts of conflict occurred between Mita and Sargon; eventually, Mita would accept tributary status in 709 b.c.e., but Sargon would never be able to conquer the Mushki territory outright. While bragging that he subjugated Mita’s land, he would state in his annals he conquered territory “up to the land of Mushki,” implying he still couldn’t take the heartland. After 709, Sargon’s annals would not mention Mita again.

Certainly, Ezekiel’s account of a notable “prince of Meshech” dates over a hundred years after Mita’s reign. But in light of Ezekiel’s description of Meshech being militaristic, led by a strong leader and a natural ally for smaller countries to coalesce around (as did peripheral states with Mushki, including the Syro-Hittites), Mita is an interesting parallel and pattern of comparison.

What About Tubal?

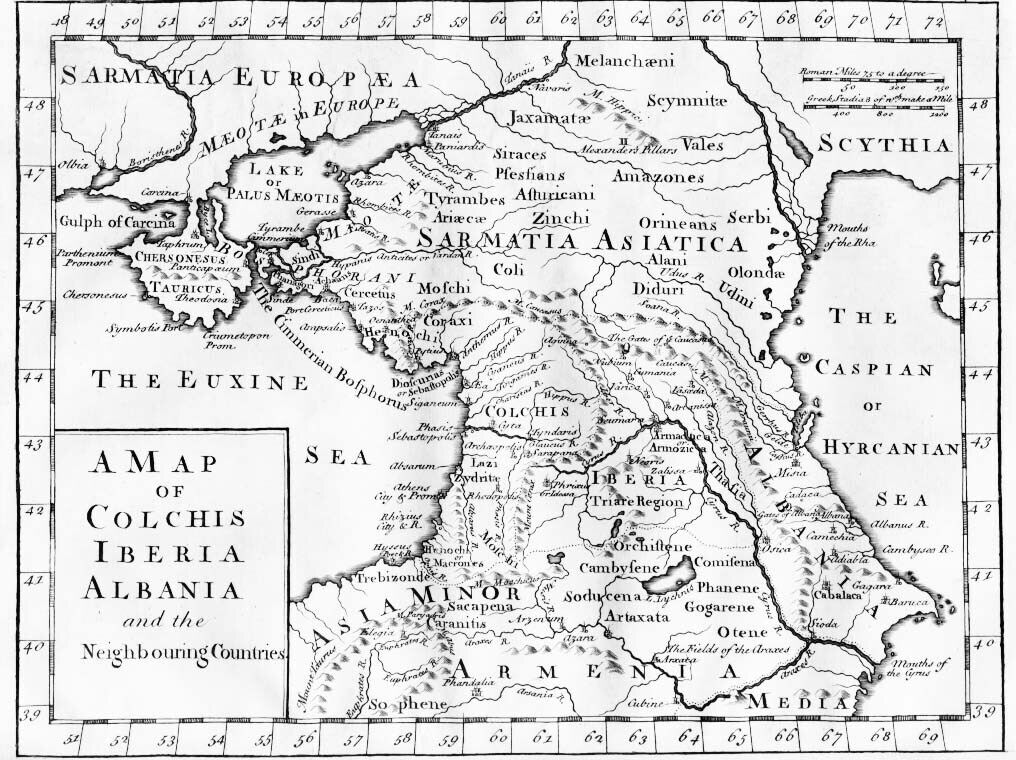

Mushki was not the only Anatolian territory causing Assyria problems. Nearby was a region called Tabal, which scholars associate with the biblical Tubal.

Compared to the Mushki, tracing Tabal’s history is more of a mystery. Like the Mushki, its territory was in eastern Anatolia. Historians track Tabal’s development as one of the Syro-Hittite states, with Tabal as one of the northernmost and largest of these states.

We don’t actually know what the people of Tabal called themselves; “Tabal” is the name given to them by the Assyrians. Furthermore, Assyrian records indicate two uses for the name: one, the actual kingdom with a definite border and government; two, the general region surrounding the kingdom (even if not a part of the kingdom of Tabal proper). This can create some confusion when recreating Tabal historiography.

The clearest picture given to us by the Assyrians is that Tabal included several related states situated next to each other in Anatolia, with the kingdom of “Tabal proper” being the most powerful among them. From Assyrian descriptions, it appears Tabal’s general northern border was at the Halys River (known in Turkish as the Kızılırmak), which flows from central Anatolia into the Black Sea.

The historical record’s first mention of a king of Tabal is Tuwati i. Assyria’s King Shalmaneser iii mentions fighting him in his western campaign of 837 b.c.e. Shalmaneser claims to have pillaged Tuwati’s land, forcing him to hide in his royal city of Artulu. The location of this city remains enigmatic: Trevor Bryce, in The World of The Neo-Hittite Kingdoms: A Political and Military History, speculates Artulu is located near the southernmost bend of the Halys. Tuwati may also be mentioned in an inscription of the Urartian King Argishti i (circa 787–766 b.c.e.) that mentions “the land of the sons of Tuate,” implying Tuwati i founded a dynasty.

The last member of Tuwati’s dynasty was Wasusarma. This king we know a little more about thanks to the Topada Inscription, discovered near the town of Acıgöl in central Turkey. Written in Luwian hieroglyphs on an exposed rock face, the opening section of it reads as follows (as translated by Lorenzo d’Alfonso):

[Great] King Wasusarma, Great King, the Hero … the mighty, proclaimed here: The king of Prizu(wa)nda and eight (rulers) of higher and lesser status were [hostile?] to me. Three kings were supportive of me: Warpalawa, Kyakya, and Ruwanda, the charioteers. I arose with the royal cavalry and set up my border-fort. The Prizu(wa)ndean rushed with the chariots towards the borders against me. (Then) he went with his cavalry and the whole army to impose his own border here, and placed them up on the mountain. I gladdened my soul … thanks to my royal cavalry. It galloped for a second time, and I gladdened my soul again. It then moved with courage into the territory of Prizu(wa)nda. … and it burned the city and its buildings and brought the booty, the women and the children into slavery.

Some points of note from this inscription: Similar to Mushki’s Mita, Wasursama shows himself as the leader of a coalition of peoples. Also of note is the level to which his army relied on horses and cavalry. Centuries earlier, the Bible records King Solomon trading in horses with “all the kings of the Hittites” (1 Kings 10:29), reflecting the Syro-Hittite world’s fragmented nature from that time on. Verse 28 further specifies the land of “Keveh,” or “Que” (see map, above), which was a neighboring Hittite state. The region around Tabal evidently was famous for its horses—Ezekiel 38 attests to this, with verses 4 and 15 noting Meshech and Tubal as a land of horsemen. Verse 15 notes “all” of their army “riding upon horses.”

As powerful as Wasursama portrayed himself to be, Tabal wasn’t strong enough to withstand Assyria. Wasursama ruled as a tributary of Tiglath-Pileser iii and would eventually fall out of favor with him, subsequently being deposed by the Assyrian monarch and replaced with Hulli, a “nobody” (i.e. commoner). Hulli would later be deposed by Sargon ii and replaced with his son, Ambaris. Ambaris seems to have gotten along well with Sargon, who allowed Ambaris to marry his daughter and granted him new territory to the south. Some believe this to be Sargon’s attempt at turning Tabal into a buffer zone between Assyria and Mushki.

Yet despite Sargon’s benefits, Ambaris didn’t want to stay under his rule. It was under Ambaris that Tabal joined an anti-Assyrian coalition Mita and Mushki were assembling.

Unlike Mita, Ambaris wasn’t powerful enough to keep Assyria at bay. Sargon captured Tabal, deported Ambaris and his family to Assyria, settled Tabal with Assyrians and made it a province. Sargon also placed Warpalawas ii, king of the vassal Tuwana, over parts of Tabal proper.

We don’t have much further record of Tabal’s relationship with Mushki at the time. But visual depictions of Warpalawas show him wearing Mushki-associated clothing. This and other clues suggest Tabal was increasingly falling under Mushki cultural influence—under the influence of a single leader of both entities, as hinted at by Ezekiel.

After Sargon’s death, Assyrian records of both Mushki and Tabal are mostly silent.

From here, especially on into the following millennium, speculation abounds as to the identity of the Meshech and Tubal polities, with a key case made that these continued to migrate north and east, eventually becoming the key east and west capitals of Russia—Moscow and Tobolsk (for example, as documented by the 16th-century Sir Walter Raleigh)—and in turn relating to other discourse on the identity of Gog and Magog.

There is still much that remains unknown about these two civilizations. Most of the archaeological evidence for and about them comes from their Assyrian enemies, primarily from a comparatively brief window within the first part of the first millennium b.c.e. But the evidence does paint a strikingly similar picture to that developing in the biblical account: Two entities (Mushki and Tabal) with parallel names (Meshech and Tubal) and prominence given to the former, first-listed; both of them located far to the north of the Holy Land, in the same general direction as peoples including the Greeks and Medes; both with visible military cultures especially prioritizing the use of horses; and, at times, both united in alliance, led by a prominent “exalted one.”