Most are familiar with the biblical account of Noah’s ark—the vessel that saved Noah, his family and pairs of all land-dwelling animals from the Great Flood. Fewer are familiar with the parallel ark/Flood accounts from the ancient world. Accounts such as the more than 4,000-year-old Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, relaying the story of Utnapishtim and his ark, with parallels to the biblical account right down to the species of birds released upon landing. Another example is the Babylonian Epic of Atra-hasis, with parallels including the entrance of animals into the boat two-by-two.

Fewer still are familiar with a 2,700-year-old Babylonian map that actually purports to give directions to the location of Noah’s ark (or rather, Ziusudra’s ark—as he is referred to in the Babylonian account—a name meaning “He of Long Life”). This map is known as the Imago Mundi—otherwise known as the Babylonian Map of the World.

This ancient, rudimentary clay tablet map has been making headlines around the world recently, with its “Noah’s ark” connection framed as being the result of brand-new research. Actually, this research is not “new”—reporting on this piece seems to have stemmed simply from a recent video uploaded to the British Museum’s YouTube channel, with Dr. Irving Finkel summarizing the artifact on Series 9, Episode 5 of Curator’s Corner.

With renewed interest in this item in the public sphere, now is an opportune time to revisit this remarkable artifact and its most intriguing reference to the location of the ark.

Map of the World

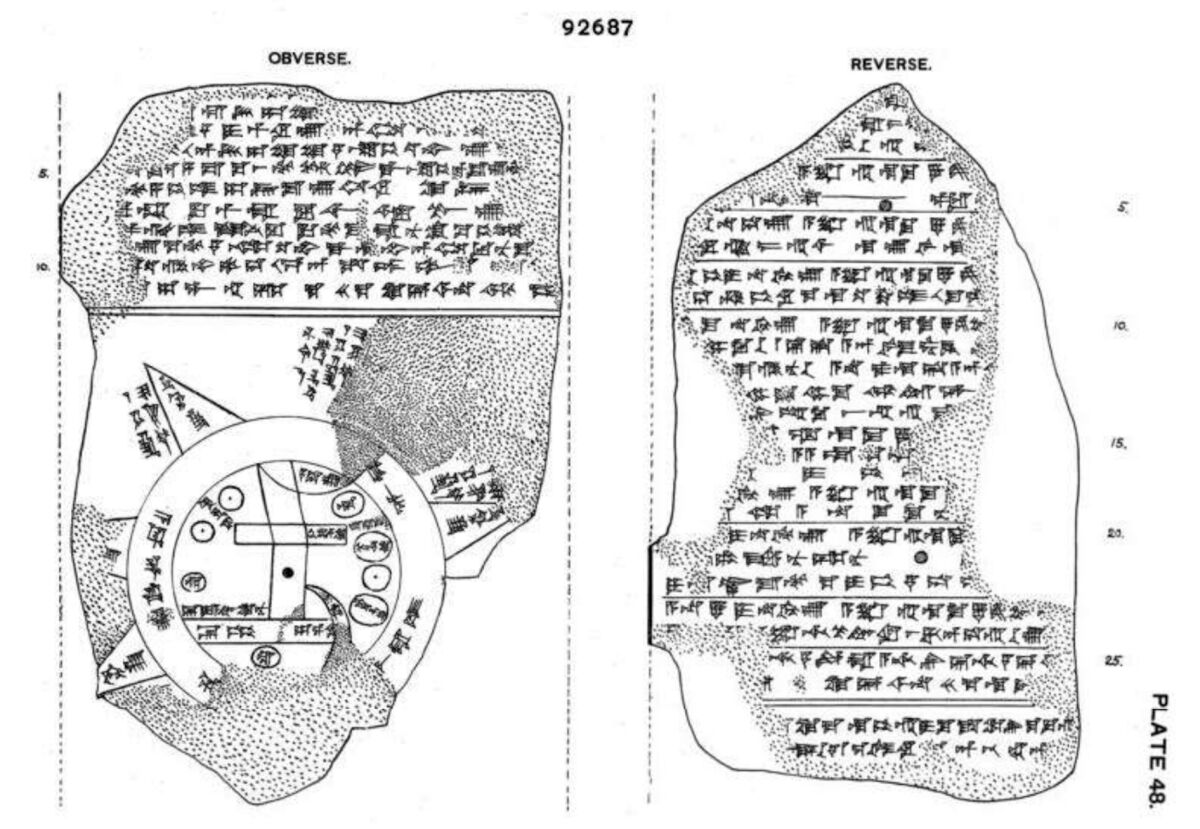

The British Museum contains around 150,000 cuneiform tablets—comparatively few of which are on display; the vast majority are kept in archive and awaiting research. Among its vast collection, the Imago Mundi stands out as one of the most significant and recognizable pieces. The item was acquired by the British Museum in 1882, following the excavations of Assyriologist Hormuzd Rassam at Sippar (central Iraq). The tablet’s obverse (front) bears a circular, rudimentary “map” with several lines of text above, and a reverse bearing additional text explaining the map in more detail. Dating at the earliest to the ninth century b.c.e.—or more likely somewhere closer to the seventh century b.c.e.—the item is famous as being the oldest map of the known world.

The outer circular rim of the map is marked with cuneiform text describing it as the “Bitter River”—essentially surrounding, figuratively, the known Mesopotamian world. Within this circle is a rectangular north-south river, which represents the Euphrates. This river is intersected near the top by a rectangle representing Babylon, a city bisected in antiquity by the river. Around the inner periphery of the circular map are several small circles, each representing cities and tribes. The Persian city of Susa is located at the bottom of the map.

Most interesting, for our purposes, are the triangular extensions protruding from the map. These represent—again, very rudimentarily—mysterious mountainous territories at the limits of the known world. Though most of these triangles are missing, there would have originally been eight of them, and they correspond specifically to divisions of text on the reverse of the tablet, which explain these locations in more detail.

The trouble was, as originally discovered, only three triangles were preserved on the map, and it was next to impossible to try to relate them to the list of explanations on the back of the tablet. That is, until the mid-1990s, when a student of Dr. Finkel’s—Edith Horsley—found a miniature fragment with a triangle on it in the British Museum archive. The fragment slotted perfectly into a gap within the Imago Mundi, and with this triangle’s key words contained within it (the “Great Wall”), it was possible to identify the reverse text block relating specifically to it, and thus the order of the rest of the text relating to the triangles.

Of particular note was a section of text relating to triangle (or “mountain”) 4.

‘Parsiktu-Vessel’

The fragmentary reverse text relating to this triangle reads:

[To the fo]urth, to which you must travel seven lea[gues, …]

[The …] … are as thick as a parsiktu-vessel; 10 fingers [thick its …]

To the casual observer, this may not seem to carry much significance. But to an experienced Assyriologist, it is immediately attention-grabbing. As Dr. Finkel explains in the recent video:

It says you see something … “as thick as a parsiktu-vessel.” This parsiktu measurement is something to an Assyriologist which makes their ears prick. And the fact is, it’s only once otherwise known from cuneiform tablets. And it’s rather an interesting cuneiform tablet, too. Because it is the description of the ark, which was built, theoretically, in about 1800 b.c.e. by the Babylonian version of Noah [as related on the Babylonian “Ark Tablet”]. And in this account, the details are given: the god says, you have to do this, this and this; and then the Babylonian Noah said, I did this, this and this, I’ve done it, and I made these structures as thick as a parsiktu-vessel, he says out of his own mouth, in the original story.

So this word parsiktu is like a kind of alarm noise; it immediately locks into this thing on the map, immediately and incontrovertibly. So what it means, speaking plainly … is that if you went up this mountain all the way … eventually you would see against the night sky, or the dark sky of the outer universe, silhouetted the ribs made of wood, as thick as a parsiktu-vessel, of the wreck of the Babylonian ark, which, like the one in the Bible, came to rest on a mountain.

That’s not all. There is another title of particular interest, engraved on the map next to this mountain. Dr. Finkel continues:

If you come down the mountain and cross over the water, back to the homeland, the first place you’d come to is called Urartu. It’s drawn on the map. Now the interesting thing about that is that, in the Bible, Noah, in his ark, landed on a mountain where the name is Ararat. And Ararat is the Hebrew equivalent of the Assyrian Urartu. …

It shows that the story was the same, and of course, that one led to the other. But also, that from the Babylonian point of view, this was a matter-of-fact thing: That if you did go on this journey, you would see the remnants of this historic boat, which saved all the life of the world … still there in the crags against the dark sky.

Accounts of Visitation

It’s a remarkable archaeological discovery. Yet while the Imago Mundi is unique as an artifact, it is not unique in describing the place of the ark as a specific location in which its remains can still be visited.

The first-century historian Josephus relates the following, in retelling the story of Noah in Antiquities of the Jews: “[T]he Armenians call this place, The Place of Descent; for the ark being saved in that place, its remains are shown there by the inhabitants to this day.” He then quotes the early third-century b.c.e. Babylonian historian Berossus (among others):

Now all the writers of barbarian histories make mention of this flood, and of this ark; among whom is Berossus the Chaldean. For when he is describing the circumstances of the flood, he goes on thus: “It is said there is still some part of this ship in Armenia, at the mountain of the Cordyaeans; and that some people carry off pieces of the bitumen, which they take away, and use chiefly as amulets for the averting of mischiefs.”

Hieronymus the Egyptian also, who wrote the Phoenician Antiquities, and Mnaseas, and a great many more, make mention of the same. Nay, Nicolaus of Damascus, in his ninety-sixth book, hath a particular relation about them; where he speaks thus: “There is a great mountain in Armenia, over Minyas, called Baris, upon which it is reported that many who fled at the time of the Deluge were saved; and that one who was carried in an ark came on shore upon the top of it; and that the remains of the timber were a great while preserved” (Antiquities 1.3.5-6).

Fast-forwarding several centuries later, the Talmud relates another peculiar account, alleging that the Assyrian King Sennacherib himself visited the site of the ark, retrieving a plank from it and fashioning it into an idol called Nisroch:

Sennacherib went and found a beam from Noah’s ark, from which he fashioned a god. … He said: “If that man (referring to himself) goes and succeeds [in battle], he will sacrifice his two sons before you.” His sons heard his commitment and killed him. This is the meaning of that which is written: “And it came to pass as he was worshipping in the house of Nisroch his god that Adrammelech and Sarezer, his sons, smote him with the sword, and they fled to Ararat” (2 Kings 19:37), where Noah’s ark had come to rest (Sanhedrin 96a).

It’s an interesting story in light of the familiar biblical account of Sennacherib’s murder—not least because of the otherwise-unusual biblical reference to Ararat (some translations give “Armenia”; the Hebrew reads, literally, “Ararat,” though the regions are broadly seen as synonymous). Further, “Nisroch” (נסרך) is a deity entirely unknown in the Mesopotamian pantheon. The word has traditionally been related to the Aramaic word neser (נסר), meaning “board” or “plank.”

This unusual story in the Talmud might not be as far-fetched as it seems: Sennacherib’s fifth campaign led him into these regions of Urartu. In fact, one of the mountains in this region—bearing inscriptions carved into the rock faces by Sennacherib’s workmen—just so happens to be a contender for the location of Noah’s ark (Mount Judi). Sennacherib’s own palace contained stone quarried from this mountain.

But perhaps Sennacherib’s visit, and deference to, such a location should not be so unusual. After all, he may well have been following a map not too dissimilar to one dating to the very same period in circulation among his very populace—the Imago Mundi.