Designing a home in Iron Age Israel would have been much easier than it is today. While the sizes of homes varied and construction materials differed, Israelite homes generally followed one standard layout.

Understanding the quintessential Iron Age Israelite home can not only give us a better understanding of biblical stories and the ancient setting, but also confirm some important details of the Hebrew Bible, including the territorial boundaries of the united kingdom under kings David and Solomon.

Archaeologists generally refer to the classic Israelite home as a “four-room house.” Several of these homes have been excavated across Israel. According to Prof. James McLellan, the four-room home “may be the most studied structure within the Southern Levant” (“Formation of Identity Through Material Canonisation in Iron I Israel”).

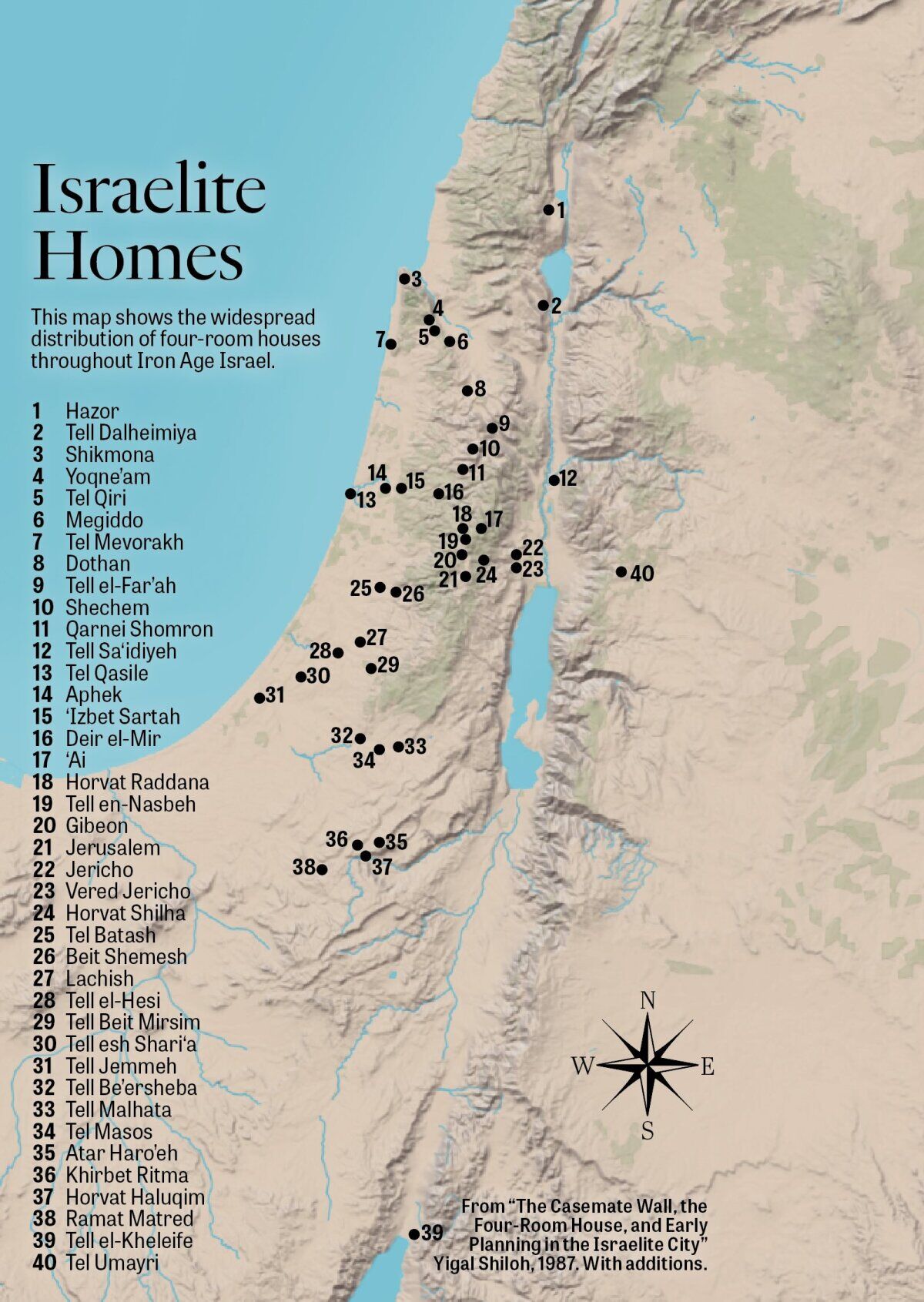

There is clear evidence identifying when these homes became prevalent. “Today we can safely date the beginning of this type to the 12th century b.c.e.,” wrote Prof. Yigal Shiloh (“The Casemate Wall, the Four-Room House, and Early Planning in the Israelite City”). Archaeology reveals the four-room style remaining in use till Judah’s destruction in 586 b.c.e.

McLellan wrote that the four-room house became “canonized” into Israelite society, meaning this design was so ubiquitous that it became an essential part of Israelite culture. “Such a feature holds a special, unalterable character in the same way that canonical books cannot be removed, replaced or edited.” Prof. Avraham Faust wrote that the four-room house was “used by rich and poor, in cities and in villages and farmsteads, and even for public buildings and tombs” (Contextualizing Jewish Temples).

These structures are clearly a key feature of ancient Israel, which means they provide unique insight into its national identity, particularly during the period from the development of the monarchy through to the Babylonian destruction. And they give insight into Israel’s most captivating period: the kingdom of David and Solomon.

The Basic Layout

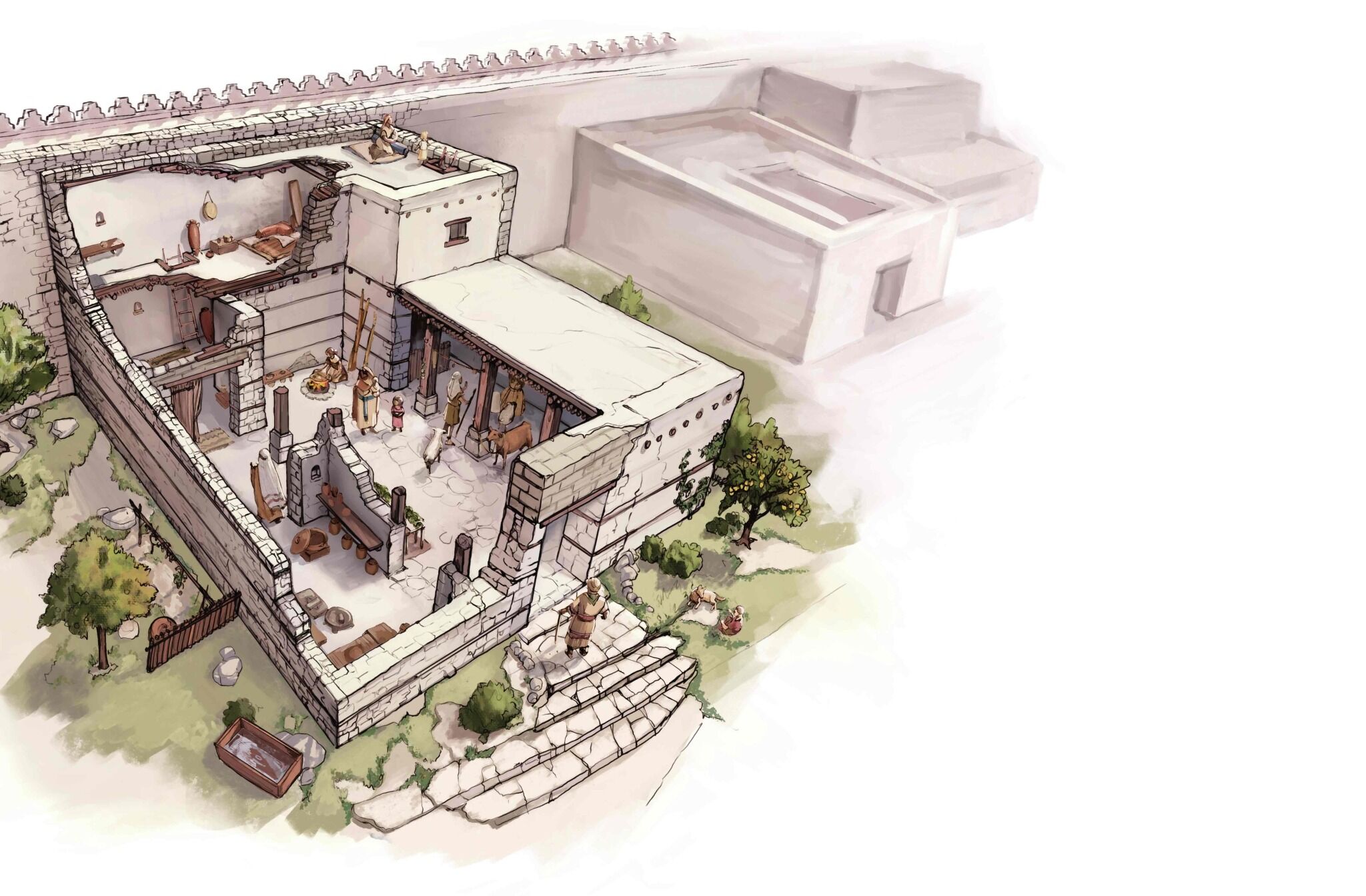

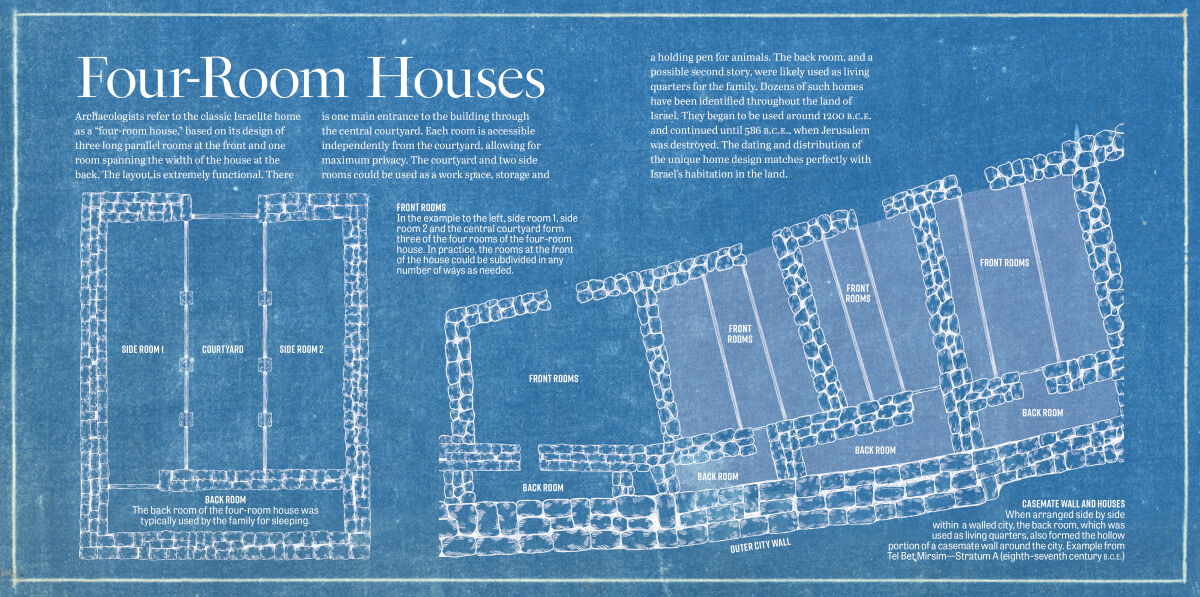

According to Professor Shiloh, “The principal feature of the four-room house and its subtypes is a back room the width of the building, with three long rooms stemming forward from it” (“The Four-Room House: Its Situation and Function in the Israelite City”). Not all of these “rooms” were fully enclosed, however. The front middle room often functioned as a type of courtyard, or gathering space. The two rooms on either side were used for storage or livestock care, and were usually separated by pillars, curtains, or segments of walls. The broad room in the back was generally fully enclosed, and this was where the family members slept. These broad rooms were sometimes two stories, with the second story being accessible by a ladder or stairs.

“The Iron i four-room houses discovered throughout the hill country typically measured 10 to 12 meters long (33 to 40 feet) and 8 to 10 meters (26 to 33 feet) wide,” Prof. Douglas R. Clark wrote. “The broad room extending across the back end of the building may have been 2 meters (6.6 feet) wide …” (“The Human Investment in Constructing a ‘Four-Room’ House”). Without subtracting the width of the walls of these homes, they would be about 80 to 120 square meters, or 850 to 1,300 square feet.

Thanks to archaeological excavation, we know these four-room homes were built as both stand-alone units and in clusters with shared walls. In some cases, they were built to form a belt of broad rooms, producing part of a settlement’s casemate walls. (For more on casemate walls, see ArmstrongInstitute.org/957.)

While the layout generally was the same, in some cases, the four basic rooms were subdivided into distinct spaces and used for different purposes.

There are dozens of mentions in the Bible of Israelite homes. Though they are not described in tremendous detail, the text provides enough detail to allow corroboration between the biblical description and archaeology.

For example, archaeologists have concluded, based on material remains, that Israelite homes had flat roofs. In Jeremiah 32:29, God condemns the houses “upon whose roofs they have offered unto Baal, and poured out drink-offerings unto other gods, to provoke Me” (see also Jeremiah 19:13). 2 Samuel 11:2 indicates that King David spotted Bathsheba bathing on a rooftop. Both activities from these biblical examples would require flat, sturdy roofs.

We know too that many four-room houses were at least partially two stories. The Bible has many indications of two-story homes with an upper chamber. 2 Kings 1:2 records, “And Ahaziah fell down through the lattice in his upper chamber that was in Samaria ….” The Hebrew word for upper chamber is aliya (äéìò) and can be translated as loft, parlor or room on the roof. 2 Kings 4 records the Shunammite woman building a living space for the Prophet Elisha, and the same word for chamber (aliya or äéìò) is used. In verse 21, it says that the Shunammite woman “went up” to lay her son on Elisha’s bed.

The Bible also indicates that timber was used alongside stone in the construction of the roofs and ceilings of ancient homes. Jeremiah 22:14 condemns the man who says, “‘I will build me a wide house And spacious chambers’, And cutteth him out windows, And it is ceiled with cedar, and painted with vermilion.” This too is confirmed by archaeology. Signs of wooden rafters and pillars have been discovered at Tel Qasile, Tel Batash, Lachish and Tel Harasim (Amihai Mazar, “The Iron Age Dwellings at Tel Qasile”).

Construction Materials

Building a home is never an easy task. In Iron Age Israel, it would have been far more labor intensive than it is today. Floors in Israelite homes were often made of rammed earth or flagstone. At the Iron Age site of Tel Umayri, the earthen floor was mixed with clay and ash, making the floor harder and smoother.

Flagstone floors required builders to source large quantities of flat stones. Several stones from a floor at Umayri probably had to be carried by at least two people. Over 8 tons of rocks were gathered to cover less than half of the house.

Constructing walls was also difficult. Professor Clark estimated it would have taken four men and one donkey “approximately one month of concentrated labor to collect stones for and construct the exterior walls of the first story” of a two-story home at Umayri. For homeowners who had other responsibilities (farming, tending livestock or industrial work), the process would have taken longer.

We know too that the walls of Israelite homes were often coated with plaster, which was made primarily of lime. A worker would have to collect large quantities of limestone, heat it until only lime remained, and then mix it with a fine aggregate like sand. “Although the technology involved in the production of lime plaster is relatively simple,” Clark wrote, “the expense in raw materials and manpower is great.”

Homes were also constructed using man-made bricks, made from a mix of straw, clay and water. This too was backbreaking work. According to Prof. David Oates, “Mud-brick was by far the most common building material employed in the ancient Near East, and its use persists in the countryside to the present day” (“Innovations in Mud-Brick: Decorative and Structural Techniques in Ancient Mesopotamia”). Oates estimated that 100 mud-bricks required about 60 kilograms (132 pounds) of straw, requiring almost one third of an acre of cultivation.

Workers had to harvest a substantial amount of lumber for ceilings and roofs. Wooden beams ran across the tops of walls or pillars to hold up the structure’s roof. Rafters also ran between the beams, as shown in a four-room house at Tel Qasile. Atop these beams, brush was layered and then covered by mud, clay or plaster. Roofs required constant maintenance, especially during the rainy season.

A Few Examples

How many of these homes have been uncovered in excavation? According to Professors Faust and Shlomo Bunimovitz, “Hundreds of four-room houses are known today from Iron Age sites mainly concentrated in the highlands (i.e. the Galilee), the Central Hill Country and the Transjordanian Plateau” (“The Four-Room House: Embodying Iron Age Israelite Society”).

Numerous four-room houses have been uncovered at Beersheba, one of Israel’s southernmost towns. In 1996, salvage excavations uncovered an Israelite home that revolved around a 12½-meter-long (41 feet) courtyard. Archaeologists believe “this structure served as a large residential dwelling during Iron iib–iic” (“Be’er Sheva, Ramot Neighborhood, Site 49”). The walls were made of limestone. The pillars separating the rooms were 1 meter apart. Unusually, the house had a staircase that led to a second floor. The first floor was made of ash and tamped chalk, with a slightly higher plaster floor on the western side of the building. Four hearths were discovered inside the building.

At Tel Halif, an archaeological site in the northern Negev, archaeologists uncovered an eighth-century b.c.e. structure called the “K8 House.” This house was clearly built in the four-room configuration. The house is about 7.5 meters by 6.8 meters (25 feet by 22 feet). The three long rooms were separated by pillars. On either side of the courtyard, one of the rooms was divided in half; the other was divided into thirds.

Wall construction methods vary within this single structure. The foundation is made of fieldstones, but the upper half of the structure is mud-brick. The floors are a mixture of cobblestones and beaten earth.

Most of the rooms also revealed evidence of food preparation and food storage (Rooms 2, 3, 4 and 5), containing jars for food, liquids and seeds. The floor of Room 3 was covered by fieldstones and possibly mortar. People would have entered through Room 6, which contained a ladder ascending to the roof. The central courtyard contained storage jars, cookware, a few lamps and a saddle quern (used for grinding grains). Unfortunately, the broad room (Room 1) has eroded. It is unclear which discoveries came from the second floor and fell during the home’s conflagration, but the K8 House at Tel Halif provides a rough understanding of the items within an Israelite home and insight into the activities the families were generally engaged in.

Megiddo has a large public structure built in the four-room style called “Palace 6000.” The walls were built of ashlar stone. Portions of the walls were plastered. Some of the floors utilized ashlars; other areas were packed earth and crushed chalk. Prof. Israel Finkelstein described the structure as a “large, monumentally built, almost square, four-room house” (Megiddo IV). Archaeologists have theorized what this structure was used for: a “residency, palace, citadel and/or tower” (“Palace 6000 at Megiddo in Context”). It is evident that this four-room layout was used for more than just the average Israelite home; in this instance, the design was used in a large public building or royal structure.

At Beth Shean, Prof. Amihai Mazar discovered a four-room house that he called “one of the largest Iron Age ii dwellings excavated in Israel thus far, and probably served as the residence of a high-ranking family” (“Tel Beth-Shean: History and Archaeology”). Each of its rooms was subdivided into two, creating six rooms in total.

The house is about 100 square meters, not including the second story. There is debate over whether the size of a house is related to the size or wealth of the family. Though both surely were factors, Mazar concluded, “Many biblical sources relate to wealth distinctions in Israelite society, and it can be surmised that the size of a house reflects the wealth of the family rather than the social structure of its inhabitants” (Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean 1989–1996).

Professor Mazar discovered signs of domestic industry such as food preparation, weaving and storage. This building is notable because there is no indication that it was used for livestock care, showing this high-ranking family was evidently not engaged in agricultural enterprises like the common Israelite family.

Four-room homes have been discovered as far north as Hazor. Prof. Yigael Yadin described one as “the most beautifully planned and preserved building among the Israelite structures at Hazor.” Unusually, it was a stand-alone home in the middle of the city.

Including both the first and second floor, it is estimated to be about 160 square meters (around 1,720 square feet), making it abnormally large. Professor Faust wrote, “Its size clearly demonstrates that it was inhabited by a large and wealthy family” (“Socioeconomic Stratification in an Israelite City: Hazor VI as a Test Case”). This home is also notable for the quality of its construction.

At least five other four-room houses have been discovered and documented in Hazor, all in the vicinity of this larger home. These homes are only about 70 square meters, and they all tend to share walls. Archaeologists have studied the disparity between these structures and the large structure to better understand the difference in living conditions between the wealthy and the average household.

Of the hundreds of four-room homes that have been discovered, these five cities exemplify the wide geographical distribution of the four-room home throughout Israel. Numerous other four-room houses have been studied at a variety of other sites, including but not limited to the City of David in Jerusalem, Tel Shikmona, Tel Batash, Tel Miqne-Ekron, Khirbet ed-Dawwara, Tel Umayri, Izbet Sartah, Tel Masos, Nahal Yatir, Tel en-Nasbeh, Khirbet Qeiyafa, Shechem, as well as in several excavations among the rural areas of the central highlands. These and other sites represent the Negev, the Shephelah, Sharon, Upper and Lower Galilee, the Transjordan, the central country of Israel and even Philistia.

Addressing the Outliers

Are four-room homes unique to Israel? The discovery of a few four-room homes outside of Israel has led some to question the association with Israel. Two homes discovered in the Philistine site of Tel esh-Sharia led one scholar to conclude that “the ‘four-room house’ originally belonged to the Philistine architectural tradition and was later adopted by the Israelites” (The Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land 1978). Another “four-room house” dating to the early 12th century b.c.e. was discovered in Thebes, Egypt. However, it violates one of the principal features of a four-room house: Its entrance is in the rear broad room. The similarities between it and an Israelite four-room house seems merely coincidental.

The primary arguments against the Philistines inventing the four-room house relate to distribution and dating. While there have been a few four-room homes discovered outside the geographic boundaries of Iron Age Israel, archaeological evidence of the four-room house is much more abundant inside Israel’s borders. Rather than prove that Israel copied another culture, the presence of these houses actually shows Israel’s cultural influence on its neighbors.

There has not yet been any evidence of four-room homes from the Canaanite period. This domestic architectural style seems to be a unique Israelite invention. Professor Faust concluded, “Thus, even if some other people used it occasionally, the Israelites used it extensively, and it is legitimate to label it as the Israelite house.”

Why So Popular?

There are several theories that explain why the four-room house, which originated in the central highlands, become a distinct cultural feature of the Israelites.

Professor Shiloh said it seems “eminently reasonable” that the four-room house design evolved out of Israel’s tents, “however, the proof for this theory still comes from the ethnographic-sociological sphere rather than from archaeological data.”

Several archaeologists have suggested that the four-room house became so widespread because of its functionality. Since each room was accessible by the central courtyard, certain rooms in an Israelite home could be made private. You didn’t have to pass through one room to enter another—unlike many Canaanite and Philistine homes. Biblical scholar Moshe Weinfeld believes this architectural feature was a function of the Torah, which required separation or quarantine for people at certain times, such as a man’s avoidance of a woman during menstruation or if a family member became sick.

The Israelite home was also functional from an agricultural perspective. One of the front rooms was often used for the care of domesticated animals; in fact, many of the homes had stalls. The Passover lamb, for instance, would be accommodated in the Israelite home for four days of every year. The Bible refers to a “fatted calf” many times, which could also be translated “stall-fed calf.” The front three spaces of the home were also utilized for other domestic production efforts, like making pottery, weaving clothes, pressing oil, grinding grain, and preparing food.

Though functional, the four-room house fell out of use at the beginning of the sixth century b.c.e. “Its disappearance from the archaeological record in the sixth century b.c.e. is quite sudden,” Faust and Bunimovitz wrote. “No functional explanation can account for the house’s sudden loss of popularity. If the house was so suitable for ‘peasant life’ in the Iron Age, why did the peasants living in the Neo-Babylonian and Persian periods stop using it?” (op cit).

Consider also: The four-room house was utilized by both the rich and the poor, who lived vastly different lifestyles. It was also used in public buildings for entirely different purposes. These factors seem to indicate that the four-room house was adopted for cultural and ethnic reasons.

Professor Faust writes that the four-room house can be defined by an “ethos” of “egalitarianism and simplicity,” which he says are features of Israelite society attested to both archaeologically and biblically.

“We believe that the four-room house embodied Israelite society and values and can be seen as a microcosm of the Israelite world,” Faust and Bunimovitz concluded. They focus that statement primarily on the importance of the Israelite family unit in Israelite culture. In ancient Hebrew, the word for “house” (úéá) is almost synonymous with family or dynasty, as is reflected in the Bible and in discoveries like the Tel Dan Stele, which describes the Davidic dynasty as ãåã úéá.

Prof. Shimon Dar believes that some of the large four-room houses discovered in rural settlements of Israel housed an extended Israelite family. The term “father’s house” is used throughout the biblical account from this period. In Judges 6:15, for instance, Gideon says, “Oh, my Lord, wherewith shall I save Israel? behold, my family is the poorest in Manasseh, and I am the least in my father’s house.” Jepthah was similarly cast out of his “father’s house.” It is unclear how literally the term “house” should be taken, but the strong association between these two words shows how essential the Israelite home was to the Israelite family and, thus, to Israelite culture.

‘An Architecture of Power’

Though four-room houses were in use prior to the 10th century b.c.e., they were located in the central hill country of Israel and Judah and were not the primary architectural style. Notably, it is exactly in the time period of kings David and Solomon that the four-room home design became common throughout Israel.

Professor Faust wrote, “[T]hese ‘formally’ designed houses, which are often large and nicely built, are now (in Iron iia) found over a much larger area, including the Shephelah, the Sharon, the northern valleys, the Negev highlands and the Aravah” (“The ‘United Monarchy’ on the Ground”). This is further evidence of a kingdom united under one monarch and central administration that exported order and culture.

Faust suggested that the growth in popularity of the Israelite-style house was actually a purposeful decision by a central Israelite administration. He said its growth in unanimity across an expanded territory “shows that the form was rather abruptly selected at the very beginning of the Iron Age ii to transmit a certain message—an architecture of power; hence its formal plan, nice execution … and very wide geographical distribution” (emphasis added).

The Israelite administration from Jerusalem would have commissioned the construction of public buildings, like the one at Megiddo, to be done in the blueprint of a four-room house. It’s clear that the campaign to establish four-room homes throughout the kingdom was successful. Archaeology shows that both the southern kingdom of Judah and the northern tribes of Israel continued constructing Israelite-style homes long after the split.

Archaeology has given us unique insight into the domestic sphere of the ancient Israelites. Many biblical accounts feature an Israelite home. Understanding the layout of those homes helps us understand the environs that shaped biblical characters and events. As Sir Winston Churchill said, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

The Israelite home was an outgrowth of ancient Israel’s unique culture, and it undoubtedly continued to shape the Bible’s foremost nation at its most fundamental level.