Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Hazor was one of the most significant sites in the Holy Land. Its power was widely felt before the arrival of the Israelites, and it would have been one of the main lynchpin cities for them to conquer, “for Hazor beforetime was the head of all those kingdoms” (Joshua 11:10). Hazor would also later become a powerful Solomonic fortress. Yet for all the important finds made at this historical site, a debate rages here as to how they match up with the biblical record, especially of Joshua and his conquests. We’ll examine this dispute, as well as the wider history of this once-formidable city-fortress, the largest site in all biblical Israel.

Canaanite Hazor

Like cities throughout the rest of Canaan before the Israelite arrival, Hazor was subservient to the Egyptian empire, though preserving a degree of autonomy. This was a chief city of Canaan, and was the biggest in the region for its time period, with a population of around 20,000. It is no wonder then that it was called the “head of all those [Canaanite] kingdoms.” Canaanite Hazor, as it functioned within the several hundred years before the Israelites arrived, was found to contain many cultic objects, a large altar, rock-cut tombs, and infant jar-burials. The plethora of finds from this period include Egyptian items, attesting to the strong Egyptian influence of the site. Additionally, the strong presence of the pre-Israelite site is witnessed by a number of ancient inscriptional references to it by neighboring kingdoms.

When we look for evidence pointing to the arrival of Joshua and the Israelites, or perhaps the intervening years during the judges period, we run into the major Hazor dispute. What immediately takes center stage is a noticeably thick layer of burning and destruction discovered throughout the city and dated to around 1233 b.c.e. This is where the debate begins regarding the historical accuracy of biblical Hazor and Joshua’s conquests.

https://soundcloud.com/watchjerusalem/digging-ancient-shiloh

Those who take the full biblical record literally know that the Israelites would have entered the Promised Land just before the start of the 14th century b.c.e.—specifically around 1407-1406 (based on verses such as 1 Kings 6:1 and Judges 11:26). Thus, many of the original Israelite conquests would have to be dated to the turn of that century. The conquest of Hazor by Joshua is well documented in the Bible. The city was utterly wasted and destroyed by fire. Yet the destruction revealed archaeologically at Hazor dated to nearly 200 years later than the Bible’s account. Thus, some hold up Hazor as one of the strongest evidences that the Israelites must have entered the Promised Land at a later date, pushing the Exodus around 150 years or more later. Those taking a “late Exodus” position thus dismiss biblical passages such as 1 Kings 6 and Judges 11 as being inaccurate, with the judges period being highly compressed into a short period. What really happened?

Deborah and Hazor

Let’s do some detective work. If the destruction layer at Hazor dates to the late 13th century b.c.e., and biblical account of Joshua’s takeover of Hazor took place around 1400 b.c.e. (the start of the 14th century), the question begs asking: Does the biblical record say that Hazor faced any further conquests after Joshua’s time? Perhaps in a period fitting the scientific dating of Hazor’s thick destruction layer? The Bible indicates that it did.

During the period of the judges, Deborah was a prophetess when Israel was subjected to the reign of King Jabin of Canaan as punishment for rebellion. Where in Israel did Jabin decide to settle? Wisely, it was the very same location that had been, for Canaan, “the head of all those kingdoms.”

“And the Lord sold them into the hand of Jabin king of Canaan, that reigned in Hazor; the captain of whose host was Sisera, which dwelt in Harosheth of the Gentiles” (Judges 4:2).

God delivered the eventually repentant Israelites from this oppression after a major battle at Mount Tabor between Jabin’s captain, Sisera, and the Israelite commander Barak. The Canaanites were vanquished, and Sisera was killed by an Israelite woman, Jael, to whom he had fled for safety.

But what of Hazor? The Bible is silent in direct reference to the city itself. King Jabin’s forces had been overcome at Mount Tabor. But we have a clue about what must have happened to Hazor at the end of Judges 4:

“So on that day God subdued Jabin king of Canaan in the presence of the children of Israel. And the hand of the children of Israel grew stronger and stronger against Jabin king of Canaan, until they had destroyed Jabin king of Canaan” (verses 23-24; New King James Version).

Jabin, king of Canaan, who was based at Hazor, was “destroyed.” This was plainly in a later, non-described battle than the initial one against Sisera. These verses make this plain—that after the initial battle (verse 23), the Israelites grew stronger and stronger until they finally had overthrown Jabin. And where would they have overthrown him? Of course, where Jabin was based—Hazor! Jabin had established a strong Canaanite presence there for 20 years (verse 3). In order to utterly defeat Jabin himself, as verse 24 describes, an assault on Hazor must have been necessary. This only makes sense. And the utter destruction described in verse 24 matches the nature of the destruction found at Hazor. Thus, we have a link between the 13th-century destruction layer discovered at Hazor and the time period of Judges 4.

But it is not as simple as that.

Jabin and Jabin

The name of the Canaanite king during the time of Deborah was Jabin. But interestingly, the name of the king of Hazor when Joshua conquered it was also Jabin (Joshua 11:1). Thus, some hold out that these kings must have been the same person—that the Bible account is confused, and that Joshua 11 and Judges 4 are two descriptions of the same historical event, one that took place after a late Exodus and late conquest of the Promised Land. Could this be true? Is the biblical account somewhat corrupted relating to the historical fate of Hazor under Joshua and under Deborah?

Archaeologist Douglas Petrovich has written a thorough response to this question and the broader subject of Hazor’s early destruction. His article can be found here. In it, he writes (emphasis added throughout):

The tension [with regard to the “Jabin” question] dissipates, however, once the reader understands that the term “jabin” is not the name of the king, but rather is a royal, dynastic title. … [T]he use of this ancient name dates back to the Mari archives of the 18th century b.c.e., where Yabni-Adad is mentioned as the king of Hazor [“Yabni” being a form of the biblical word “Yabin,” which is then anglicized to “Jabin”]. The proposal of a dynastic use of “jabin” for the king of Hazor in both Joshua and Judges thus has sufficient merit ….

So we see a “Jabin” as king over Hazor during the 18th century b.c.e., based on the Mari archives; a “Jabin” as king over Hazor during the 15th century b.c.e., based on Joshua 11; and a “Jabin” as king over Hazor likely during the late 13th century b.c.e., based on Judges 4. Thus, the name “Jabin” fits well as a common title, similar to that of “pharaoh.”

Joshua’s Conquest

Finally then, if Hazor’s thick destruction/burn layer is attributed to the time of Deborah, and if a number of dynastic “Jabin” kings ruled over Hazor, what of Joshua’s destruction? Again, the Bible is very clear about the destruction of Hazor under Joshua.

“And Joshua at that time turned back, and took Hazor, and smote the king thereof with the sword: for Hazor beforetime was the head of all those kingdoms. And they smote all the souls that were therein with the edge of the sword, utterly destroying them: there was not any left to breathe: and he burnt Hazor with fire” (Joshua 11:10-11).

Based on this passage, are we therefore to conclude that this simply cannot have happened—that the Bible was in error? Archaeological finds at Hazor have more to say.

Excavations have uncovered remnants of an earlier destruction layer at Hazor, dating to this Late Bronze period—around 1455-1400 b.c.e. A destroyed temple, or high place, was found dating to this time. Furthermore, a large pit was found dug through an ancient Hazor pavement, the sides of which cut through a visible early destruction layer containing ash and fallen bricks—also evidencing this earlier violent demolition! Petrovich continues, in his article:

[T]he Hazor of Joshua’s day clearly was destroyed by a massive conflagration as well. … Various sections of the burnline and residual burned areas, which measure half of a meter in some places, have been preserved …. This burnline, visible throughout the excavated area, reveals the unmistakable signs of a great conflagration. … Admittedly, the scope of this conflagration has yet to be determined fully, due to the relatively few spots on the site that were excavated down to the level of Late Bronze I.

So we see that a violent attack also occurred toward the end of the 15th century b.c.e.—fitting squarely into Joshua’s time period. This destruction is perhaps unfairly overlooked, thanks to the significant later 13th-century destruction layer that has been more widely revealed. Yet its existence cannot be denied.

It is regarded scientifically as simply “unclear” who was responsible for this earlier attack on Hazor. Yet the archaeological record does square up with what the Bible says, despite any confusion. Describing the specifics of this earlier destruction, archaeologist Bryant Wood writes in his article “Let the Evidence Speak”: “Significantly, cultic centers seemed to have been singled out for especially harsh treatment by the conquerors.” Such “especially harsh treatment” of Hazor’s pagan cultic areas would constitute very typical evidence of an Israelite attack.

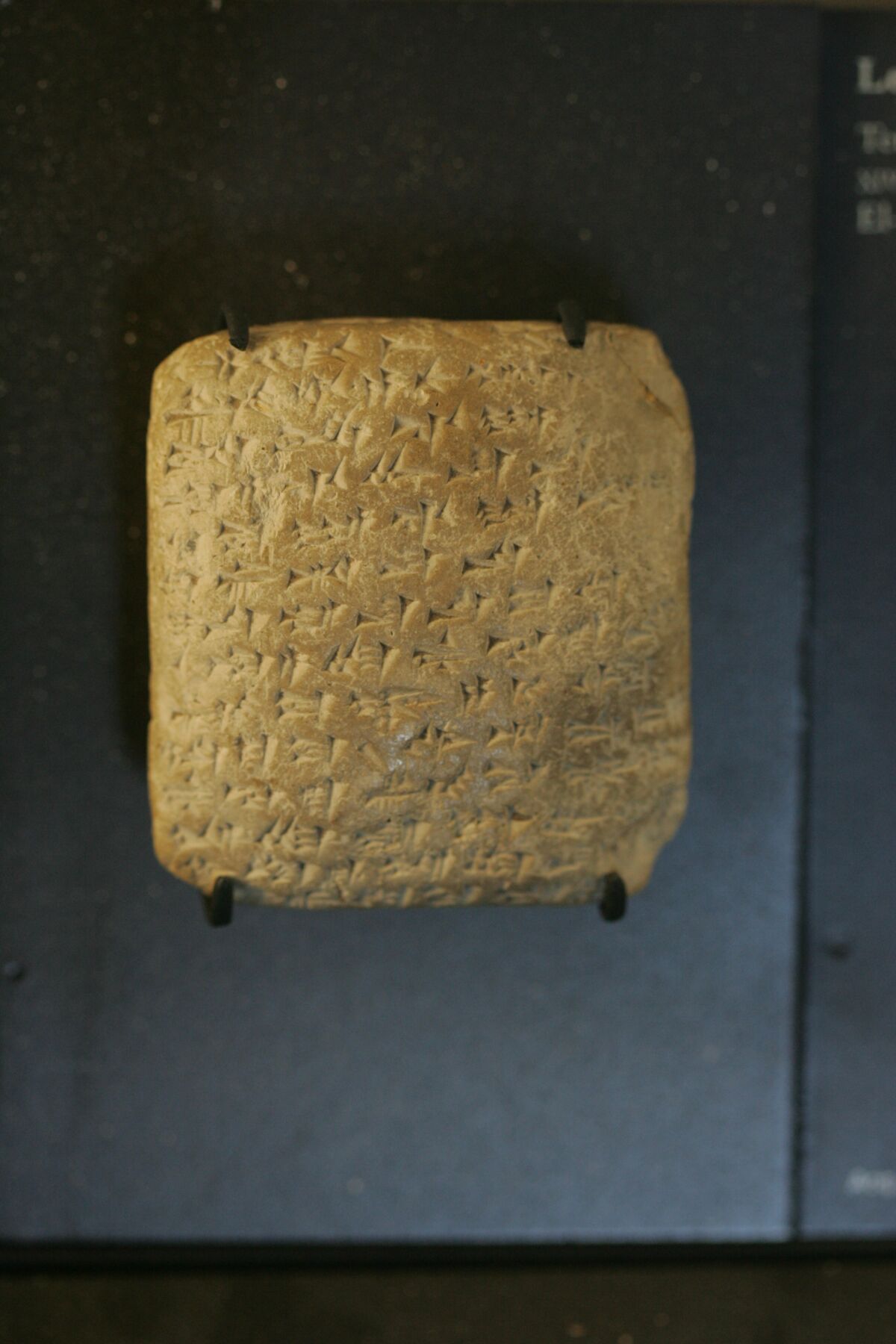

Amarna Letters

In spite of the archaeological ambiguity of the attackers of late-15th-century Hazor, we can glean a potential extra-biblical clue as to who they were from the Amarna Letters. These letters—a trove of clay documents found in Egypt, dating to around the end of the 15th century—have been discussed previously in this series. The letters were sent from Canaanite kings desperately calling on Egypt for help against the invading nomadic Habiru people. The linguistic similarities between the names Habiru [also “Hapiru” or “Apiru”] and Hebrew are unmistakable, and the Habiru invasions have been dated to the same time period as the Israelites’ entrance into the Promised Land.

Hazor is only briefly mentioned in this archive, here noted in a message from the king of Tyre:

To the king [the Pharaoh], my lord, [m]y god, my sun … The king of Ḫaṣura [Hazor] has abandoned his house and has aligned himself with the Apiru [or Habiru]. May the king be concerned about the palace attendants. These are treacherous fellows. He has taken over the land of the king for the Apiru. May the king ask his commissioner, who is familiar with Canaan.

Thus this letter provides support for the Habiru as those responsible for taking over Hazor—the time frames of the earlier destruction at Hazor, the Amarna letter, and the Israelites’ arrival into Canaan all match.

As more evidence comes to light, theories and ideas will change. Certain established dates may fluctuate. Yet the Bible’s account continues to stand validated—the evidence thus far accumulated, though sometimes piecemeal, continues to prove the entire biblical account of Hazor, rather than disproving any of it!

Solomonic Construction

After the Canaanite rule at Hazor was again subdued, Israelites settled the city. Once King Solomon came on the scene, Hazor experienced massive rebuilding.

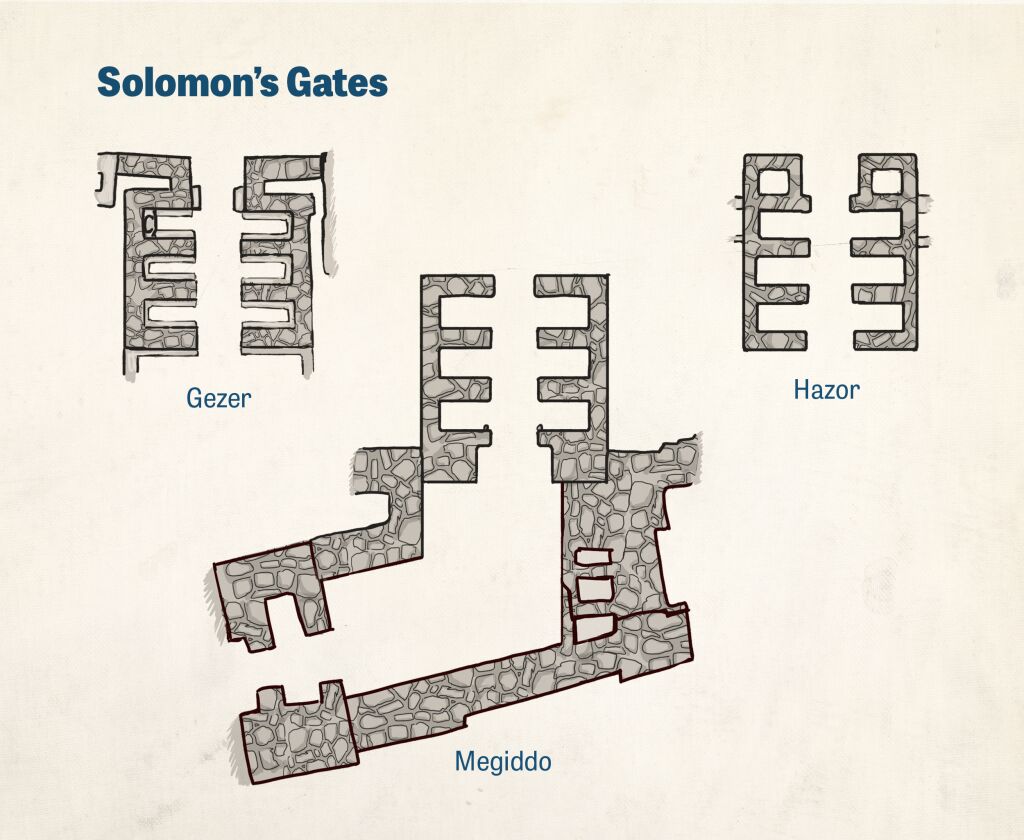

“And this is the reason of the levy which king Solomon raised; for to build the house of the Lord, and his own house, and Millo, and the wall of Jerusalem, and Hazor, and Megiddo, and Gezer” (1 Kings 9:15).

This verse also has been explained earlier in this series regarding the cities of Megiddo and Gezer. As should be expected, related architectural features dating to Solomon’s time have been found in all three of these cities—these are the six-chambered gates. These gate patterns show proof of a strong united kingdom of Israel during the Solomonic period, exerting a regulation of building standards over a wide area of land. This goes against a popular school of modern thought that considers Israel to have been a fragmented, uncontrolled spread of nomads during the time of David and Solomon—and that David and Solomon themselves, if they existed at all, were merely small-time tribal chieftains.

Hazor saw further building under the reign of King Ahab. (As one of the northernmost cities in Israel, Hazor went along with the northern kingdom of Israel after the rebellion against King Rehoboam.)

Destruction

Hazor would be hammered repeatedly throughout the ensuing years. Asa, king of Judah, stripped the temple of its treasures to pay the Syrian King Ben-hadad to attack the belligerent northern kingdom of Israel. Ben-hadad obliged, and Hazor was one of the cities that faced destruction from his armies (1 Kings 15:20; “all the land of Naphtali” includes Hazor—see Joshua 19:32, 36). Hazor also weathered attacks by Assyrian King Shalmaneser III and then Syrian King Hazael (2 Kings 11:32-33).

And destruction from enemy kings was not all that Hazor faced. Amos 1:1 describes a major earthquake that occurred in Israel around 750 b.c.e. According to modern research, Hazor was one of the closer Israelite cities to the probable epicenter. One of Hazor’s excavators, Yigal Yadin, found tilted walls and collapsed floors attributed to this earthquake. Other related earthquake-evidence of the same period was found at five other archaeological sites—a witness to the powerful event described in biblical and extra-biblical sources.

Hazor eventually fell to the Assyrians during the campaigns of King Tiglath-Pileser III in 732 b.c.e.

“In the days of Pekah king of Israel came Tiglath-pileser king of Assyria, and took … Hazor, and Gilead, and Galilee, all the land of Naphtali, and carried them captive to Assyria” (2 Kings 15:29).

The archaeological finds from Hazor corresponded with this destruction. And after this point in the city’s history, it would never rise again to its prior, mighty status.

Hazor would see small settlement, though, from the seventh to second centuries b.c.e. Evidence of this has been found at the site. And again, this evidence should be expected; Nehemiah tells us that the “children of Benjamin” who returned to the land after their captivity during the Persian period dwelt in Hazor (Nehemiah 11:31-33).

Hazor Today

There was an interesting future prophecy made by Jeremiah against Hazor specifically:

“Flee, get you far off, dwell deep, O ye inhabitants of Hazor, saith the Lord; for Nebuchadrezzar king of Babylon hath taken counsel against you … And Hazor shall be a dwelling for dragons [jackals], and a desolation for ever: there shall no man abide there, nor any son of man dwell in it” (Jeremiah 49:30, 33).

And so to this day, no one lives at Tel Hazor. It is possible that this has been the case for the past 2,200 years, from the time that the small second-century b.c.e. Hellenistic settlement ended. Hazor is now a national park and ongoing excavation site that continues to yield up fascinating clues verifying the biblical account of this important city—the old ancient “head of all those kingdoms.”

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer