In the July-August issue of Let the Stones Speak, we interviewed Hebrew University archaeologist Prof. Yosef Garfinkel. The interview focused on a paper published in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology in which Professor Garfinkel demonstrated similarities in the design, construction and material presence of five fortified 10th-century b.c.e. Judahite sites.

In his paper, Professor Garfinkel suggested that the construction of five urban centers during the same time period and using essentially the same blueprint demonstrates the presence of a centralized government in Jerusalem.

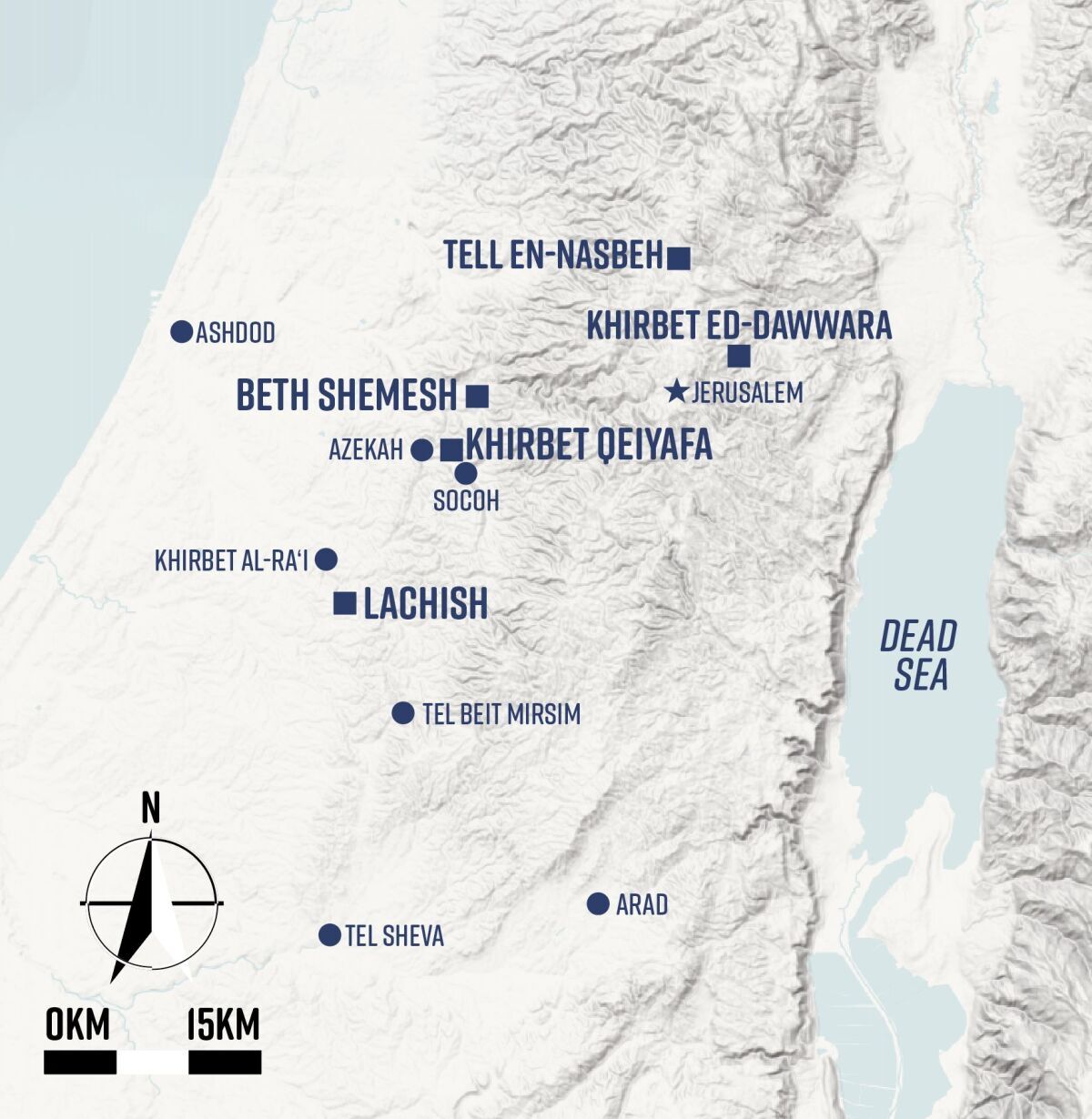

This is a novel and fascinating approach to the study of the kingdom of Judah during the time of King David. In researching his paper, Professor Garfinkel focused on five separate archaeological sites: Khirbet Qeiyafa, Beth Shemesh, Tell en-Nasbeh, Khirbet ed-Dawwara and Lachish. He observed similarities in urban planning between all five sites.

The title of Professor Garfinkel’s article is “Early City Planning in the Kingdom of Judah: Khirbet Qeiyafa, Beth Shemesh 4, Tell en-Nasbeh, Khirbet ed-Dawwara and Lachish V.” The full article, with its tables and references, is available to read at Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology.

The following is a simplified, popular-format version of Professor Garfinkel’s article, edited and published with the permission of Professor Garfinkel and the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology.

Abstract

The earliest fortified sites in the kingdom of Judah in the early 10th century b.c.e. feature a casemate city wall lined with an abutting belt of houses, which incorporate the casemates as rear rooms. [See our article “What Is a Casemate Wall?” for an explanation.] This urban plan is clearly recognized in the sites of Khirbet Qeiyafa, Tell en-Naṣbeh, Khirbet ed-Dawwara and, as discussed in detail, Beth Shemesh. Recently, excavations at Lachish, Level v, uncovered a similar pattern comprising a peripheral belt of structures abutting the city wall. This city wall was solid with no casemates. These sites have far-reaching implications for understanding the urbanization process, urban planning and borders of the earliest phase of the kingdom of Judah.

Introduction

The Shephelah region, southwest of Jerusalem, was the kingdom of Judah’s most favorable ecological zone. In the Judean and Hebron hills, which constituted the kingdom’s geographical core, the slopes are steep, and the landscape’s suitability for agriculture is limited.

To the east and south, the arid and hilly Judean and Negev deserts can support a pastoral economy but not large-scale agriculture. Hence, the Shephelah, with its low rolling topography, fertile soil and comparatively substantial annual precipitation, is the only part of the kingdom where large-scale agriculture was possible, constituting it as the domain’s breadbasket and the sole part of which that could support a large population. Therefore, the kingdom’s takeover of the Shephelah and its agricultural resources was an important stage in its development.

The kingdom’s expansion in the hill country and, from there, further south and west has been the subject of several discussions in the last decade, most of which sought to defend the claim that this process took place only in the late ninth or eighth century b.c.e. However, since these articles’ publication, new data have been uncovered, suggesting that the kingdom had begun expanding in the hill country and the northern Shephelah as early as the 10th century b.c.e. and that it expanded into the southern Shephelah about two generations later.

In this paper, I examine the kingdom of Judah’s early urbanization as manifested in its known fortified settlements, five sites altogether. Three are located in the Shephelah—Khirbet Qeiyafa, Beth Shemesh and Lachish—and two are located in the hill country: Tell en-Naṣbeh and Khirbet ed-Dawwara.

Khirbet Qeiyafa IV

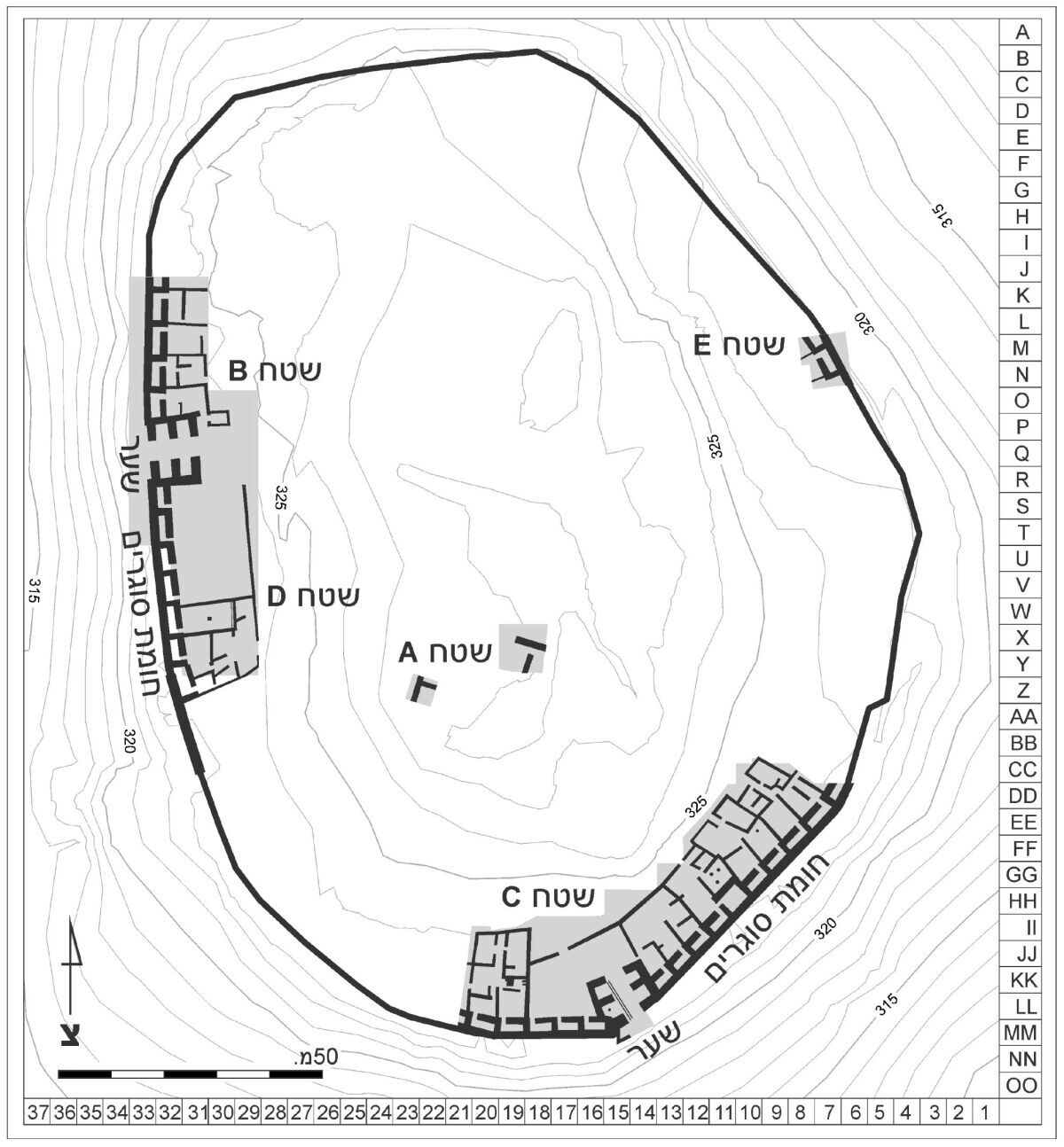

Khirbet Qeiyafa iv was a 2.3-hectare fortified city. It was located on a prominent hill overlooking the Valley of Elah, between the sites of Socoh and Azekah, and about a day’s walk from Jerusalem. The city was destroyed shortly after its construction.

In the excavated structures, hundreds of well-preserved finds were recovered, including pottery, stone tools, metal tools, ritual objects, scarabs and seals, inscriptions, botanical remains and animal bones. We excavated the site in 2007–2013. The shallow accumulations allowed us to uncover a considerable part of the city (around 20 percent), including two gates, two piazzas, a casemate city wall, a peripheral belt of buildings abutting the city wall, a large pillared building (Area F), and a major public building occupying the highest point of the site (Area A).

While the excavation results have been published in detail, three points are worth rehearsing. Firstly, the casemates are oriented away from the gates. Secondly, a peripheral belt of buildings abuts the city wall and incorporates the casemates as rear rooms. Thirdly, two inscriptions in (proto-)Canaanite script were recovered. Carbon-14 dates assign the fortified city to the first quarter of the 10th century b.c.e.

The excavation of Khirbet Qeiyafa prompted an animated debate on whether this site should be assigned to the late Iron Age i or the early Iron Age iia. The pottery supports an early Iron Age iia attribution. It includes black juglets and Cypriot black-on-white ware, barrel-shaped juglets, but lacks Philistine pottery typical of the Iron Age i. Furthermore, a detailed analysis of the site’s pottery assemblage suggests close parallels with other early Iron Age iia sites in the region, including Tel Sheva viii, Arad xii, Beth Shemesh 4, Khirbet ed-Dawwara and Khirbet al-Ra’i.

The site’s expedition conducted a comparative analysis of Khirbet Qeiyafa’s material culture against the various ethnic entities in the region: Philistine, Judahite, Canaanite and Israelite. The various aspects analyzed included urban planning, faunal assemblage compositions, stamped jar handles and female clay figurines. The observed patterns indicate that Khirbet Qeiyafa’s material culture is closest to that of sites in Judah, like Tel Sheva vii and Arad xii.

Beth Shemesh

The site of Beth Shemesh is located in the northern Shephelah, roughly a day’s walk from Jerusalem. It has been extensively excavated since 1911. The first expedition worked in 1911–1912. A second large-scale excavation project at the site was conducted in 1928–1933. It recognized that the early Iron Age ii (Stratum iia) city was enclosed by a casemate wall. A photograph of this city wall depicts two casemates built of massive stones, as would be expected for a city’s fortification. The excavation report pointed out this wall’s similarity to the well-known casemate city wall found at Tel Beit Mirsim. The existence of a casemate city wall in early Iron Age ii Beth Shemesh was accepted by numerous notable scholars.

[Yigal] Shiloh studied the layout and fortifications of Beth Shemesh. Although faced with plans that lumped together several Iron Age phases, he managed to produce a convincing blueprint of a segment of the casemate city wall and abutting houses. Indeed, close observation of the plan published for the Iron Age cities of Beth Shemesh reveals a rounded arrangement of houses in an orientation different from the other buildings and fortifications of the later cities. Striving to distinguish the early level from the otherwise undifferentiated plan, we may observe three principal components: a casemate city wall, a belt of houses that abut the city wall, and a peripheral road. From 1990 until recently, Bunimovitz and Lederman led a third excavation project at Beth Shemesh.

These excavations have significantly refined the site’s stratigraphy and provided a new numerical system for its historical sequence. This sequence comprises a Late Bronze Age Canaanite city (Levels 8–7), an Iron Age i Canaanite village (Levels 6–4), an Iron Age iia–b city affiliated with the kingdom of Judah (Levels 3–2), and, finally, an Iron Age iic horizon of ephemeral activities (Level 1). This expedition overlooked the casemate city wall addressed by Grant, Avigad, Albright, Wright, and Shiloh.

Bunimovitz and Lederman’s expedition understands Level 4 as a Canaanite village, which continues the simple social organization of the Iron Age i. They dated this village to 1050–950 b.c.e. and assigned it to the late Iron Age i. However, in their concluding remarks, they stated that “the Level 4 assemblage gives the impression of a pottery horizon belonging to the very end of Iron i–beginning of Iron ii.” Indeed, notwithstanding some differences—e.g. the absence of black juglets and Ashdod ware—the Beth Shemesh 4 pottery assemblage is almost identical to the early Iron Age iia Judahite Khirbet Qeiyafa assemblage.

Furthermore, the slight difference observed may be accounted for by the difference in scales of exposure: While around 5,000 square meters of Khirbet Qeiyafa were uncovered, only around 100 square meters of Beth Shemesh 4 were excavated. Bunimovitz and Lederman’s Level 3 marked a major change in the site’s layout, manifesting features of state organization: large public buildings, an impressive underground rock-cut water reservoir, a commercial area, a storehouse and an enormous grain silo. It was dated to 950–790 b.c.e. on historical grounds. However, its proposed foundation in the 10th century b.c.e. was heavily criticized for being based on two sherds from a fill and should probably be pushed back. Notably, the radiometric dates are not wholly consistent with the expedition’s chronological framework. They provide lower determinations for most levels, and experts called the statistical analysis underlying them into question, especially regarding Level 4.

According to these critical accounts, the Beth Shemesh 4 carbon dates fall in the middle of the 10th century b.c.e. Why did Bunimovitz and Lederman fail to recognize the urban character of Level 4? Most likely, this is because they did not excavate the Level 4 casemate wall. The spatial distribution of the excavation areas dictates, to a large extent, the understanding of the nature of Level 4. A similar issue arose regarding the site’s seventh-century b.c.e. phase. Bunimovitz and Lederman thought the site to be mostly abandoned at this time because their fieldwork concentrated on the western side of the site and missed the intensive Level 1 activities east of the mound.

Tell en-Naṣbeh

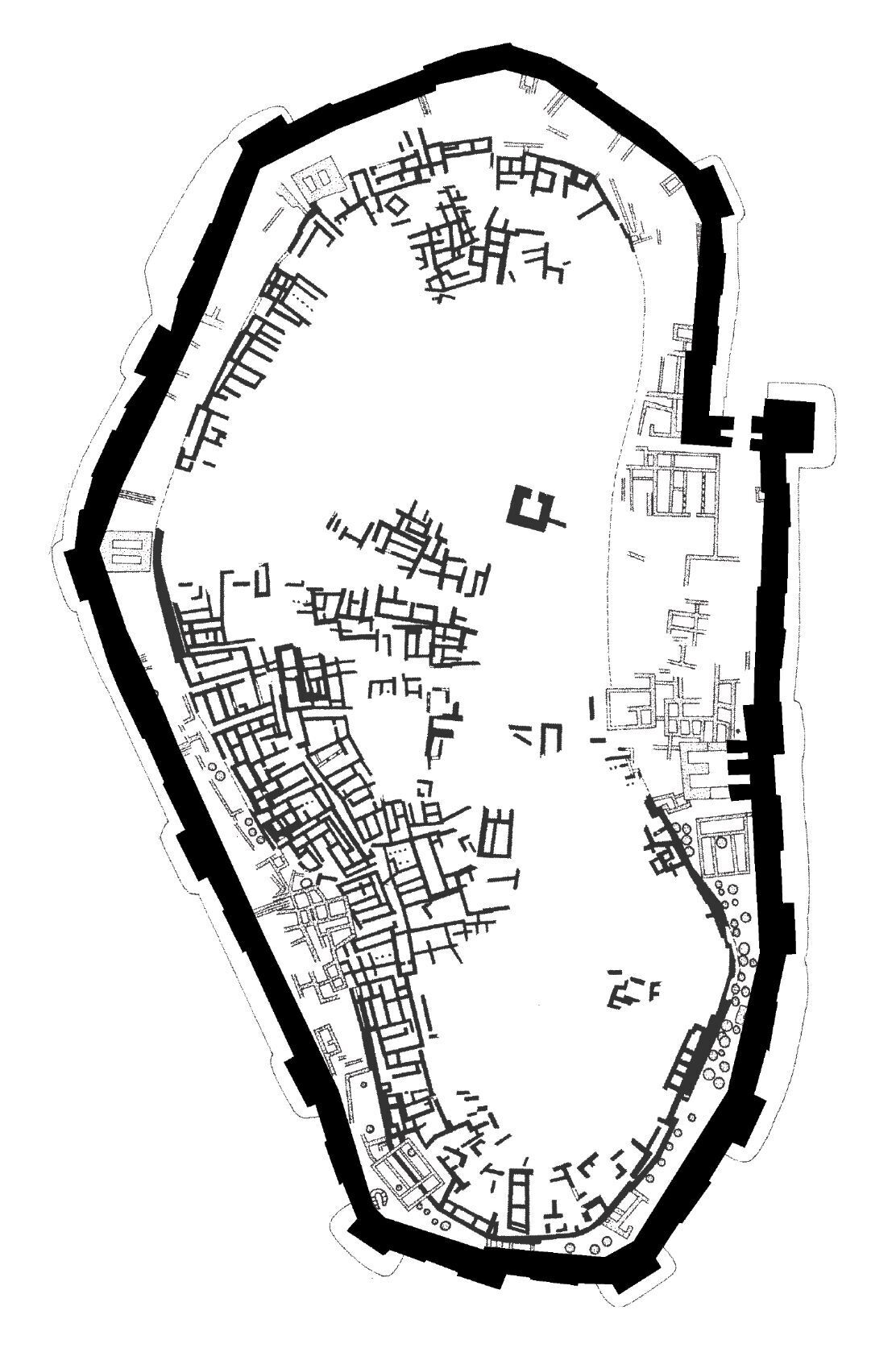

Tell en-Naṣbeh is located about half a day’s walk from Jerusalem. Badè excavated the entire site in five seasons between 1926 and 1935. The final report was published some 10 years later, and Zorn provided an updated analysis of the site [in 1993]. Among other remains, two Iron Age ii cities were uncovered. The earlier city was encircled by a casemate wall, which was lined by a belt of houses incorporating the casemates as rear rooms; on the other end, these houses opened onto a peripheral road. Additional constructions were found inside the city. About two centuries later, sometime in the late ninth century b.c.e., a second fortification system was constructed. It encircled a larger city and consisted of a massive solid offset-inset city wall dubbed the Great Wall. The dating of these two cities is not supported by radiometric dates. However, based on stratigraphic considerations and plan, it seems that the earlier city with its casemate city wall was built during the early 10th century b.c.e.

Khirbet ed-Dawwara

Khirbet ed-Dawwara is a small fortified site, only 0.5 hectare in size. It is located on the desert fringe of the Benjamite hill country, about half a day’s walk from Jerusalem. The arid environmental conditions implicated that the site could not support a large population, but its topographical position provided it with an excellent view in every direction, especially of the Dead Sea and the Transjordanian plateau to the east and the Judean desert to the east and south. Undoubtedly, it was strategically significant. Finkelstein conducted two seasons of excavations at the site in 1985–1986. He found a poorly preserved, short-lived site built on bedrock and featuring shallow accumulations. It comprised a single phase of settlement with remnants of four-room houses and a casemate fortification.

The excavator suggested that the site was occupied for two centuries and discussed it within the chronological and cultural framework of the Iron Age i. However, it featured pottery vessels similar to those of Khirbet Qeiyafa, suggesting that the site might be more suitably dated to the early 10th century b.c.e. and the Iron Age iia.

Lachish

Tel Lachish is located in the southern Shephelah, approximately two days’ walking distance from Jerusalem. The site has been extensively excavated by seven different expeditions from 1932 until today. The earliest Iron Age fortification identified by the first and third expeditions was a 6-meter-wide brick construction that encircled the entire 7.5-hectare site and is assigned to Levels iv–iii. A wide range of proposals was made concerning the dating of the early Iron Age levels at Lachish: the early 10th century b.c.e. during the time of David and Solomon, the late 10th century b.c.e. during the time of Rehoboam, the early–mid-ninth century b.c.e., and sometime after the destruction of the large Philistine city of Gath, Tell es-Safi. None of these proposals were based on radiometric dates. A recent field project conducted in 2013–2017 sought to resolve this controversy by closely exploring the city’s fortifications on the northern slope. A previously unknown 3-meter-wide city wall built of medium-sized stones was uncovered. In Area CC, a drainage channel for runoff water was recorded, and in Area BC, where the wall is poorly preserved, pillar buildings abutted its inner face. The subsequent mudbrick city wall of Levels iv–iii was built on top of these buildings, putting them out of use.

The floor running up to the city wall in Area CC produced olive pits for radiometric dating. Stratigraphically, this floor was located above the last Canaanite city of Level vi and below the mudbrick city wall of Levels iv– iii. Its ceramic assemblage included red-slipped and irregularly hand-burnished sherds. The radiometric dates, most of which represent the last years of Level v, cover the second half of the 10th century b.c.e. and the first half of the ninth century b.c.e. These results were challenged by Ussishkin, the site’s former excavator. He argued that the recently uncovered wall was a revetment of the Level iv–iii city wall, not a city wall proper. However, as discussed elsewhere, this claim disregards some critical factors and cannot be accepted.

Early Iron Age Fortifications in the Kingdom of Judah

In 1978, Shiloh recognized a particular plan that characterized early Iron Age cities. It consisted of a peripheral belt with three components: a casemate city wall, residential houses abutting the city wall, and a street. This urban pattern has been observed in at least four early 10th-century b.c.e. sites: Khirbet Qeiyafa, Beth Shemesh, Tell en-Naṣbeh and Khirbet ed-Dawwara. As Khirbet ed-Dawwara was built in an arid zone that could not support a large population, it comprised a smaller settlement. In addition, Tel Sheva and Tel Beit Mirsim applied the same urban plan in the eighth century b.c.e. The accumulation of data supports a tripartite division of the Iron Age iia:

1. The early Iron Age iia (circa 1000–930 b.c.e.) is characterized by the low quantities of red-slipped and irregularly hand-burnished pottery decoration, Cypriot white-painted vessels, early Ashdod ware and archaic (Canaanite) script. Khirbet Qeiyafa iv, Khirbet al-Ra’i, Khirbet ed-Dawwara, Beth Shemesh 4, Arad xii, and Tel Sheva vii are dated to this phase.

2. The middle Iron Age iia (circa 930–860 b.c.e.) is characterized by abundant irregularly and geometrically hand-burnished bowls, Cypriot black-on-red vessels, and early Phoenician-Hebrew script. Beth Shemesh 3 and Lachish v are assigned to this phase.

3. The late Iron Age iia (circa 860–800 b.c.e.) is characterized by red-slipped pottery, irregularly hand-burnished ceramics, and late Ashdod ware. Tell eṣ-ṣafi iv, Lachish iv, and Beth Shemesh 3 belong to this phase.

The available radiometric dates for early Iron Age iia come from Khirbet al-Ra’i vii, Khirbet Qeiyafa iv, and Beth Shemesh 4. Tenth-century b.c.e. radiometric dates have also been produced for Tel ‘Eton, but the nature of the architecture and pottery assemblage associated with them is still unclear. The dates for the middle and Iron Age iia derive from Lachish v–iv.

Most of the dates produce an orderly chronological sequence. Khirbet al-Ra’i vii is the earliest, followed by Khirbet Qeiyafa iv and Beth Shemesh 4. Although all of these sites produced a few earlier radiometric dates falling in the early–mid-11th century b.c.e., they did not include Iron Age i Philistine pottery typical of this time. Therefore, Khirbet al-Ra’i vii, Khirbet Qeiyafa iv and Beth Shemesh 4 ought to be assigned to the 10th century b.c.e. The radiometric dates from Lachish v are the latest in the sequence, falling in the second half of the 10th century b.c.e. and the first half of the ninth century b.c.e. Above, I reviewed some patterns characteristic of the two earliest phases in the development of the kingdom of Judah. Here, I offer a summary and some conclusions.

During the early Iron Age iia, the kingdom of Judah encompassed at least three cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa, Beth Shemesh and Tell en-Naṣbeh. They featured the same underlying urban plan comprised of an outer casemate city wall and a belt of houses abutting the casemates, on the one side, and facing a peripheral road, on the other. Furthermore, none was more than a day’s walk from Jerusalem and, thus, may be considered as marking the kingdom’s geographical core. They were calculably positioned to guard strategic roads leading into the kingdom: Khirbet Qeiyafa controlled the Elah Valley, Beth Shemesh controlled the Soreq Valley, and Tell en-Naṣbeh controlled the northern road to Jerusalem.

As Beth Shemesh 4 and Khirbet Qeiyafa feature the same material culture, they illuminate various aspects of the earliest phase of the Iron Age iia in Judah. Particularly notable are the (proto-)Canaanite inscriptions found in both sites. The spread of writing indicated by these inscriptions is a sign of increasing demand for communication and a marker of centralized authority.

In the middle Iron Age iia, a fortified city was founded at Lachish (Level v), occupying only the northeastern side of the mound. Unlike the earlier cities mentioned above, Lachish’s city wall was solid, reflecting its importance as a regional center as early as the second half of the 10th century b.c.e. Some scholars have argued that the kingdom of Judah’s expansion into the Shephelah occurred in the mid- or late-ninth century b.c.e. However, Khirbet Qeiyafa iv and Beth Shemesh 4 show that this process was already on its way in the early 10th century b.c.e. at sites located one day’s walk from Jerusalem. Along with the casemate walled city of Tell en-Naṣbeh, these sites mark the earliest borders of the kingdom of Judah. Toward the end of the 10th century b.c.e., the kingdom expanded its territory to a two-day walking distance from Jerusalem, primarily manifested by Lachish Level v.