The book of Daniel is probably the key book in the debate about the authenticity of the Bible. This book purports to forecast multiple world-shaking events, including the emergence of specific kings and the rise and fall of empires.

Because of its prophetic nature, many believers consider the book of Daniel evidence that a divine Being inspired the Bible. Many critics, however, dismiss this book entirely. They say it must have been written after the fulfillment of its many “prophecies” and that it is simply a clever retelling of history. To the cynics, it is impossible that such incredibly accurate prophecies could have been made in advance.

Amid this debate, one thing is certain: The historical events documented in the book of Daniel occurred. Many figures and events in this book, from the breathtaking splendor of King Nebuchadnezzar ii and the Neo-Babylonian Empire, to Alexander’s blitzkrieg destruction of the Medo-Persian empire, are powerfully corroborated by ancient texts and archaeological evidence. So the crucial question is: On which side of those events was Daniel written? Is the book of Daniel evidence of divine revelation, or is it an outright fake? How can we know which is true?

Bible believers accept that Daniel wrote during the sixth century b.c.e., the chronological period described in the text. Critics say the book was written as late as the second century b.c.e., after many of the prophecies—especially related to the Persian and Greek empires—had come to pass.

The skeptics use several arguments to make their point. For example, they claim that since Daniel used Greek words, his book must have been written during the later, deeply Hellenistic time period in Judea. They also note that there are details in Daniel that have not been corroborated by ancient history or archaeology. As such, these unconfirmed events must be the product of a late writer’s imagination.

Let’s examine these arguments.

Language

The book of Daniel is written in Hebrew (chapters 1-2:4 and chapters 8-12) and Aramaic (Daniel 2:4 through chapter 7). A number of words transliterated into the Hebrew and Aramaic are of foreign origin.

The book does contain Greek words—a sum total of three. All three words refer to musical instruments, and they are all listed together, repeated four times throughout the same chapter: Daniel 3:5, 7, 10 and 15. (For additional information, read “The Instruments of the Bible”) Does the presence of a handful of Greek words prove that Daniel was written much later than the sixth century b.c.e.?

The first Greek word is kitharis. This probably refers to a lyre or lute, known to have been in use as early as the eighth century b.c.e.—some 200 years before the traditional dating of the book of Daniel. The transliteration of this word into Daniel’s Aramaic—as kitharos—actually matches more closely with the most ancient Greek form of the word, as used by Homer in the eighth century. (The Greek kitharis had long changed to kithara by the second century b.c.e.)

The second Greek word is symphonia. Pythagoras used this word in the sixth century b.c.e. A form of this word also appears in Hymni Homerici from the early sixth century b.c.e.

Finally, the Prophet Daniel used the word psanterin, linked to the Greek word psalterion. This word probably refers to a harp. It has not yet been found in ancient Greek texts, which means there is no tangible proof it was in use in the sixth century b.c.e. Consider, however, the estimation that less than 10 percent of classical Greek writings have survived to this day. Is it rational to use one Greek word as evidence that Daniel did not write this book?

Consider also: Would it really be unusual for a handful of Greek technical terms for specialty instruments to have been used in sixth-century b.c.e. Babylonian courts? Ancient texts show there was a measure of cultural interaction between the Greeks and the Babylonians. Musical instruments are easily transportable symbols of specific cultures. It wouldn’t be unusual for Greek instruments (and even Greek artists) to feature in the Babylonian court. Nor would it be unusual for an official like Daniel, who served in both the Babylonian and Persian courts, to record their presence in a book.

What would be unusual is for a second-century b.c.e. book to be so devoid of Greek terminology. If Daniel had been written during the second century b.c.e., when Greek language and culture were saturating the region, surely it would contain more than three different Greek words.

Some scholars point to the use of Persian words in Daniel as evidence for a later date. This argument, too, is hard to substantiate. The 18 Persian words used in the book mostly refer to administrative positions. Daniel himself is clearly described as living and writing during the Persian period of rule. And six of these Persian words are not found in use after the fourth century b.c.e. All the Persian words in the book are considered “Old Persian,” indicating that the book was assembled in Persian history.

As stated above, the main body of Daniel was written in Aramaic, and bookended in Hebrew. The Hebrew is difficult to date for the periods in question, but evidence suggests that Daniel was first written entirely in Aramaic before being partially translated into Hebrew. Initially, critics believed Daniel’s Aramaic was of a late, Western Aramaic style. This belief bolstered the view that Daniel was authored at a later date. But this assumption had to be revised following the discovery of the Elephantine Papyri and Dead Sea Scrolls.

As it turns out, the Aramaic style of writing in the book of Daniel fits with the early Imperial style, a style used in the sixth-century b.c.e. period. Desperate to place authorship of this book in the second century b.c.e., some argued that the authors of Daniel must have faked an early-style Aramaic.

The book of Daniel contains about 20 native Assyrian and Babylonian words. If the book of Daniel was written in the second century, this would be unusual, considering the Babylonian Empire fell 400 years earlier.

Additionally, the book of Daniel contains specific phraseology that points to an early date of writing. For example, the phrase “Lord of heaven” was not used during the Maccabean period because at that time it was associated with the pagan god Zeus.

Analyzing it word for word, the book of Daniel as a whole was written in a somewhat older linguistic style, with more archaic terms than the books of Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah and Esther—books that are widely accepted as dating to the fifth century b.c.e. This fits, then, with the traditional dating of Daniel: the sixth century b.c.e. (For more detail on these points of language, see Craig Davis’s book Dating the Old Testament, pages 404-428.)

Historicity

It is true that certain events of the book of Daniel have not been fully verified by archaeology. Does this prove that these events must have been the invention of second-century b.c.e. ghostwriters?

Archaeological discoveries are constantly confirming Daniel’s description of life in Babylon and Persia as remarkably accurate. For example, Daniel’s descriptions of Nebuchadnezzar’s building programs, boastfulness, hasty threats and possibly even a love for cedar trees (Daniel 4) have all been confirmed archaeologically.

Numerous ancient sources, including the annals of Cyrus the Great, corroborate Daniel’s account of the fall of Babylon in 539 b.c.e. Many other historical details have also been verified, such as the binding nature of the laws of the Medes and Persians. In Persia, even a king couldn’t take back his own laws (Daniel 6; Esther 8:8). This was not the case in Babylon, where kings could haphazardly change laws (e.g. Daniel 3:28).

Archaeology has revealed an event similar to that recorded in Daniel 6, in which a Persian king decreed that a man be executed, then the man was found to be innocent—yet executed anyway. Even upon discovering the error, the king himself could not reverse his command—such was the binding nature of Medo-Persian law. According to historian John C. Whitcomb: “Ancient history substantiates this difference between Babylon, where the law was subject to the king, and Medo-Persia, where the king was subject to the law.”

As confirmed by the archaeological and historical record, the Babylonians used fire as punishment, just as Daniel 3 describes. The Persians, however, considered fire holy and thus wouldn’t have used it for such a purpose—but they did keep caged lions.

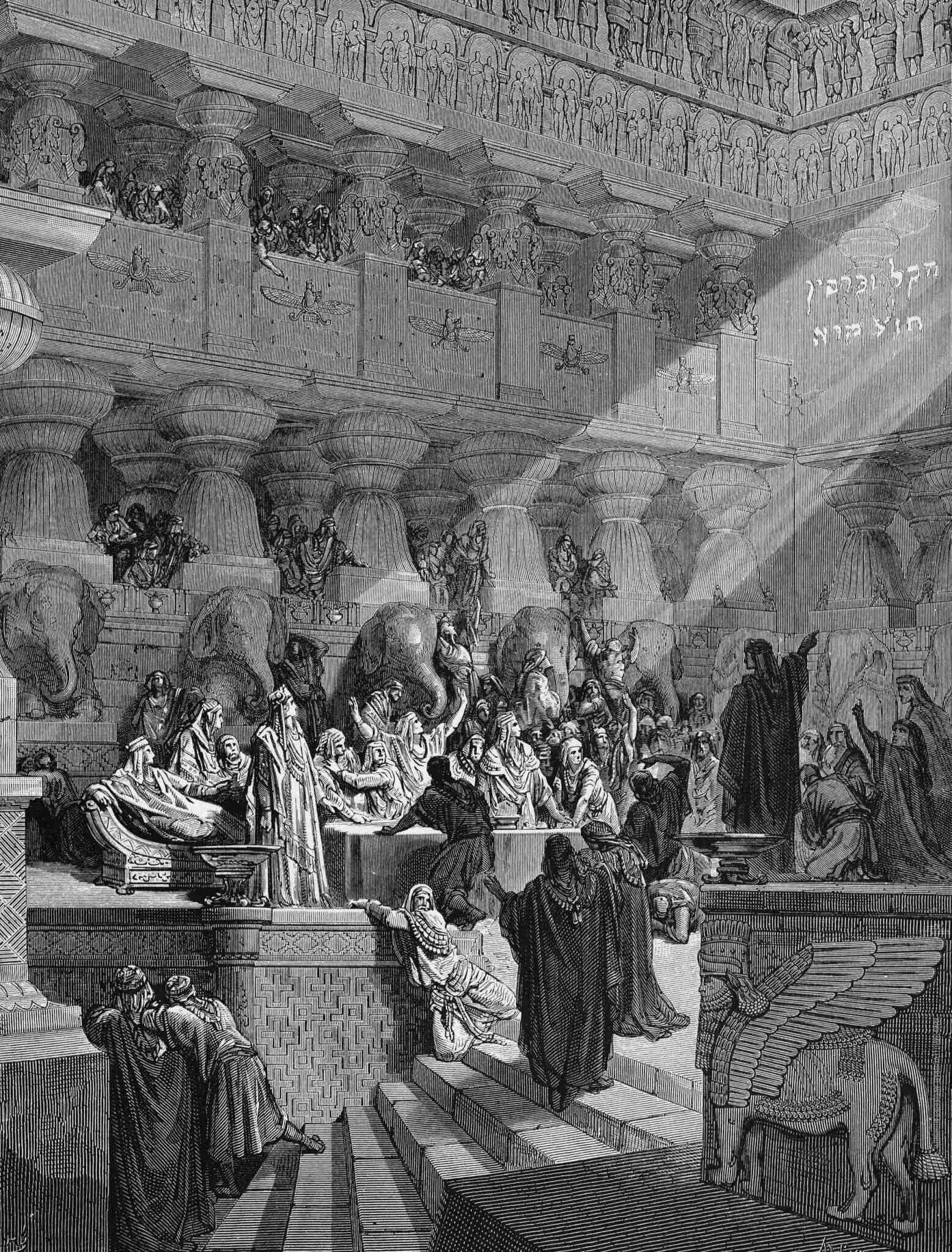

Daniel accurately detailed governmental bureaucracy—leaders and officers of the Babylonian and Persian empires—from kings to magicians to the “chief officer” (Daniel 1:3). He recorded the reign of Belshazzar, a coregent king considered fictional by the skeptics until he was proved through archaeology with a reference on the Nabonidus Cylinder. Even the famous fifth-century b.c.e. historian Herodotus does not mention this man—but Daniel does. The accuracy of Daniel’s account has been proved time and again through archaeology—even down to such minutia as the fact that the Babylonian palace walls were plastered (Daniel 5:5).

Considering the highly accurate, verifiable details in the book of Daniel, it is hard to imagine a Maccabean-period author, writing more than 300 years later and living over a thousand miles away in Judea, composing such an account.

Of course, archaeology has not confirmed and cannot confirm every word of Daniel. There remains some ambiguity over the identity of Darius the Mede, just as there was with Belshazzar until his existence was proved. But there is far more evidence attesting Daniel’s authorship than there is evidence proving it was written by someone else. And the golden rule of archaeology is that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence—it is not proof that something did not happen.

The biggest and most overlooked proof for a traditional date of Daniel, though, is the very thing that motivates a late dating: prophecy.

Prophecy

The first-century c.e. historian Josephus wrote that when Alexander the Great swept into Judea (circa 329 b.c.e.), he was met by a procession of Jewish priests. When the high priest came before the famed conqueror, he showed him from the book of Daniel where his conquests were directly prophesied. This amazed Alexander. He was moved by the revelation and gave the Jews tremendous favor (Antiquities of the Jews, 11.8.4-5). This is also recounted in the later Jewish Talmud (circa 500 c.e.).

If this account is accurate, it means the book of Daniel was written before Alexander’s time (333 b.c.e.). Naturally, the skeptics reject the record of Josephus as fiction. Yet his narrative of this wider period has been corroborated by other historical records and archaeology. Since Josephus lived 2,000 years closer to the actual events than we do, and had access to a far larger archive of since-destroyed historical material, isn’t it reasonable that he would know more about what transpired between the Jews and Alexander the Great?

The critics do not redate Daniel because science demands it. They redate it because they struggle to accept that the events it describes were written long before they were fulfilled. The only explanation they can accept for the accuracy of Daniel’s prophecies is that they were written after the events they foretold.

There is one major problem with this rationale. Dating this book to the second century b.c.e. still puts its authorship far earlier than many of the figures and events it forecasts!

If they could, the critics would claim this book was written even later—preferably in the fifth century c.e. or later. But they can’t. Why? For one, copies of the book of Daniel were discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls, which means the text was already in existence by the second century b.c.e.—thus, that is the latest date that can be assigned.

If this book was authored in the second century, this would mean its remarkable “prophecies” about the Greek Empire and Antiochus vi were written after the events they portended. But what about the events Daniel prophesied that occurred after the second century?

Daniel, in fact, prophesies primarily about the Roman Empire. He clearly described four successive world-ruling empires of man (Daniel 2, 7): first, the Babylonian; second, the Medo-Persian; third, the Greco-Macedonian; and finally, the Roman. Scholars try to make Daniel’s four empires fit before the second century b.c.e. by separating the Medes and Persians as the second and third empires, and thus making the Greek Empire the fourth. The book of Daniel, though, explicitly identifies Medo-Persia as one empire—the second—and the Greco-Macedonians as the third.

The accuracy of the prophecies about the Roman Empire is incredible. Daniel forecast that it would bring about the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple (Daniel 9:25-26)—a prophecy fulfilled in 70 c.e. He not only foretold the founding of the empire, he also described the divide between Rome and Constantinople (symbolized by the two legs of the statue in Daniel 2:33, 40-41; fulfilled in 395 c.e.), as well as 10 “resurrections” of the empire (described in symbol as “ten horns” in Daniel 7:7, 19-20, 24). Daniel also prophesied about the takeover of Rome by three barbarian tribes (verses 8, 20, 24; fulfilled in the fifth and sixth centuries c.e. by the Vandals, Heruli and Ostrogoths), followed by the emergence of the Roman Catholic Church as the spiritual head of the empire (the “little horn” of verses 8, 20-21, 25; fulfilled 554 c.e. onward).

Even if we accept a late date of authorship, the book of Daniel is still a powerfully prophetic book!

Despite all the effort to assign the book of Daniel a later date, no date is late enough to escape his prophetic timeline. This book wasn’t written for his day. The prophet himself admitted how confused he was with the prophecies. “And I heard, but I understood not; then said I: ‘O my Lord, what shall be the latter end of these things?’ And he said: ‘Go thy way, Daniel; for the words are shut up and sealed till the time of the end’” (Daniel 12:8-9).

As this concluding passage reveals, this book could not have been wholly understood, in its full prophetic context, at any other point in history—until the very “time of the end.”

God’s Word to the Skeptics

Our predecessor, the late Herbert W. Armstrong, once wrote the following: “Most highly educated people, and men of science, assume that the Bible is not the infallible revelation of a supernatural God, and they assume this without the scientific proof that they demand on material questions” (The Proof of the Bible). Such is the case with the book of Daniel. But this is not the only problematic approach. He further wrote, “Most fundamentalist believers assume, on sheer faith, never having seen proof, that the Holy Bible is the very Word of God.”

Both approaches are wrong. Science should be based on fact and firm evidence. And likewise faith, as is brought out in several Bible passages, should be educated (Isaiah 1:18; Malachi 3:10). It is right and necessary to question, to prove. And when it comes to holding a purported prophet, like Daniel, to account, God Himself instructs in Deuteronomy 18: “And if thou say in thy heart: ‘How shall we know the word which the Lord hath not spoken?’ When a prophet speaketh in the name of the Lord, if the thing follow not, nor come to pass, that is the thing which the Lord hath not spoken; the prophet hath spoken it presumptuously, thou shalt not be afraid of him” (verses 21-22).

The Bible says we must test the prophets. If they pass the test, then we must believe them.