It was a trade secret that its harvesters protected heavily. God commissioned Moses to use it in the most holy structure in ancient Israel. The Romans esteemed its value more than that of gold. What was it? Dye from a sea snail—specifically, the murex.

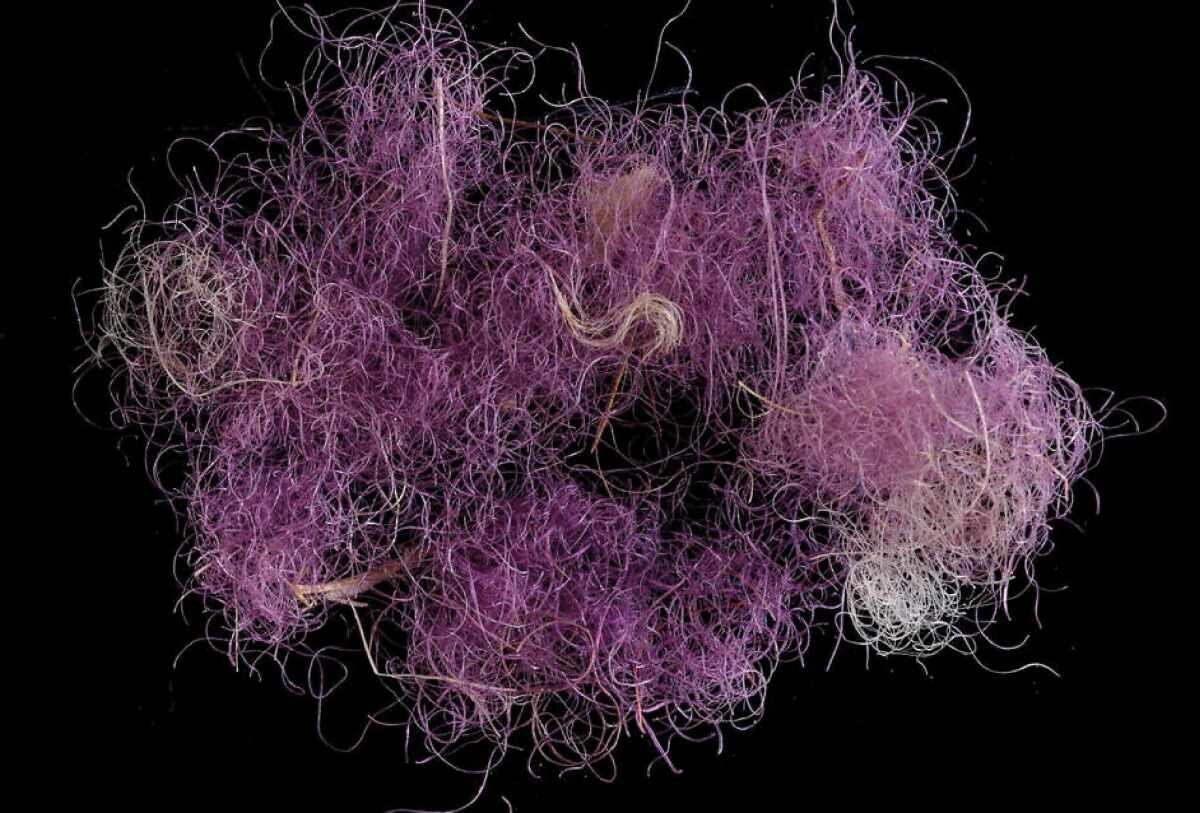

Murexes were harvested for the production of argaman, a purple dye highly prized as a luxury commodity. During the Iron Age (1200–586 b.c.e.), the Phoenicians, a seafaring people based in what is today Lebanon, had a near-monopoly on the production of this dye, also known as “Tyrian purple.” But where did they produce it?

The first ever argaman factory was discovered in Israel—at Tel Shikmona.

A Peculiar Location

Tel Shikmona is an archaeological site on Israel’s northern coast, near the modern-day city of Haifa. Originally excavated during the 1960s and ’70s, archaeologists didn’t know what to make of it. It’s not on an easily accessible harbor, making it a curious choice for a maritime settlement. It is fortified despite not being on any apparent strategic territory.

Starting in 2016, when the University of Haifa began the “Shikmona Early Periods Project,” scholars started piecing together what made Tel Shikmona so significant.

Large quantities of pottery fragments with Phoenician designs suggested a Phoenician, rather than Israelite, settlement. Analysis of purple-stained clay vats and other tools helped clarify Tel Shikmona’s purpose: It was a mass production facility for Tyrian purple. And it is the first one from the biblical era to be discovered.

Tyrian purple was a prized commodity in the ancient world. The fourth-century c.e. Roman Emperor Diocletian, in his Edict of Maximum Prices, lists 1 pound of the dye as costing 150,000 denarii—three times the value of gold.

Tyrian purple was used in the construction of the biblical tabernacle. According to Exodus 26:1, the curtains of the tabernacle were dyed “blue, and purple, and scarlet.” Exodus 39:1 shows the garments of the high priest were also dyed purple. In 2 Chronicles 2:13, the Phoenician King Hiram sent an artisan “skilful to work … in purple” for Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem. The purple dye for these projects may have come from Shikmona.

This explains some of the peculiarities of Shikmona’s location. It lacks a harbor and is close to a rocky reef, which according to Prof. Ayelet Gilboa and Dr. Golan Shalvi, two of the main scholars affiliated with the excavations, “endangered any boat approaching the shore.” Tel Shikmona’s fortifications were designed to protect its valuable cargo. Additionally, its “maritime environment is one of the best [murex] habitats along the coast of the Southern Levant,” wrote Gilboa and Shalvi.

Shikmona’s strata date from between the 11th to the sixth centuries b.c.e. in 10 different layers. The vats date to all 10 different Iron Age strata, showing both the longevity of the site and the value of its commodity. The fact that Tyrian purple stains have survived on the vats up to now shows how long-lasting the luxury dye is.

We also have an idea of who the workers at Tel Shikmona were trading with. Archaeologists have discovered large quantities of Cypriot “Black-on-Red ware” at the site. This pottery style originated in Cyprus but has been found elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean. Cyprus was evidently a major trade partner. Meanwhile, Isaiah 23 verses 1 and 12 show Cyprus (under the archaic name Kittim) as a significant area associated with both Tyre and Sidon, Phoenicia’s two leading city-states.

But in these early findings, the mysteries of Tel Shikmona were only just beginning to be solved.

A Peculiar Influence

Much of the pottery found at the site was Phoenician style. This is unsurprising as Shikmona is in northern Israel, near Phoenicia’s heartland in Lebanon. But some of the site’s other aspects suggested influence from a different group of people.

Tel Shikmona contains a casemate city wall, a primarily Israelite construction made up of two parallel stone walls with a cavity between them. In times of siege, the cavity would be filled with sand and other debris, adding an extra layer of defense. Other tels that exhibit this feature include Megiddo and Hazor. Tel Shikmona also has Israelite-style three-room houses. Both architectural elements are normally found at inland sites.

What could account for Tel Shikmona having evidence of both Phoenician and Israelite occupation? Gilboa and Shalvi believe they may have an answer. They published their findings in June in an article for the Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University.

The factory seems to have been rebuilt following destruction at the time of King Ahab. It is during this period (early-to-mid ninth century b.c.e.) when this composite Phoenician-Israelite material culture becomes especially apparent. Gilboa and Shalvi suspect that sometime during Ahab’s reign, the northern kingdom of Israel conquered Tel Shikmona for its economic value.

“The Israelite kingdom recognized the amazing economic potential of the luxury trade in argaman, and they wanted a piece of the cake,” Shalvi told Haaretz. But producing the dye “is a very traditional industry that requires deep knowledge of chemistry. Plus, it’s very stinky work, and not everyone is willing to do it.” While Israel maintained control of the site, it employed Phoenician workers.

Phoenician sites containing Israelite architectural influence are not unheard of. Phoenician colonies in Spain and North Africa show this. But the level of cultural overlap in Tel Shikmona, according to Shalvi, is unique.

There is, however, a wrinkle to this hypothesis.

A Strategic Alliance

According to the Bible, during Ahab’s reign, Israel and Phoenicia weren’t warring, but rather allied. This is best represented by Ahab’s choice of queen: the infamous Jezebel, “the daughter of Ethbaal king of the Zidonians” (1 Kings 16:31).

“Zidonian” is an early modern English designation of the people of Sidon, one of the most powerful Phoenician city-states. The first-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus calls Ethbaal “king of the Tyrians and Sidonians.” This implies that “Zidonian” was a name used for Phoenicians in general, beyond the inhabitants of the single city of Sidon.

It seems unlikely that Ahab would go to war with a realm he was allying with through diplomatic marriage. It may be possible that the city was conquered by Ahab’s immediate predecessor, King Omri. The Bible doesn’t have many details on Omri. But 1 Kings 16:16-22 show that Omri was one of Israel’s prominent generals and attained power following a civil war. Verse 27 says his reign was illustrated by “might.” He may have expressed some of this might in some coastal conquests.

Another piece of biblical evidence is found in 1 Kings 5. King Hiram of Tyre was a friend and ally of King David. This strategic alliance continued into King Solomon’s reign. Solomon took advantage of Tyre’s trade connections and skilled labor force. He asked of Hiram: “[C]ommand thou that [your servants] hew me cedar-trees out of Lebanon; and my servants shall be with thy servants” (1 Kings 5:20).

According to 2 Chronicles 2, one of Hiram’s most valued craftsmen was of mixed Phoenician-Israelite heritage, suggesting a normalized population exchange (verses 12-13). 1 Kings 9:10-13 show Solomon giving Hiram control of 20 cities in Galilee.

Meanwhile, Solomon married the daughter of Egypt’s pharaoh. Pharaoh gave Solomon the city of Gezer as a gift (1 Kings 9:16-17).

While this history predates Ahab, the precedent for Phoenician-Israelite exchanges and rulers gifting cities in the context of diplomatic marriages does exist. There is no concrete proof that the site at Tel Shikmona was a similar gift to Ahab. If this were the case, this would raise the follow-up questions of who destroyed Tel Shikmona at the time of Ahab and why. But considering Ahab’s links to the Phoenicians through his wife Jezebel, the “gift from the father-in-law” theory is intriguing. That Josephus calls Jezebel’s father king of both Tyre and Sidon may suggest he was an expansionist and could have conquered Tel Shikmona from a rival Phoenician city-state.

Gilboa and Shalvi date Tel Shikmona’s final destruction layer to the second half of the eighth century b.c.e., which would roughly correspond to when Israel was defeated and taken captive by the rising Assyrian Empire at around 721–718 b.c.e. (see 2 Kings 17).

In Isaiah 10:5-6, God poetically describes Assyria as a power charged “to take the spoil, and to take the prey, and to tread them down like the mire of the streets.” Tel Shikmona was “tread down,” but the sands of time couldn’t erase its story from historical memory. It still survives in the tel’s ruins. And like the Bible that illuminates its historical context, Tel Shikmona’s secrets are there for anybody to examine.