Hebrew University archaeologist Prof. Yosef Garfinkel recently published a paper presenting evidence that the kingdom of Judah was established by a centralized government at the time of King David. In June, Professor Garfinkel spoke with Let the Stones Speak assistant managing editor Brent Nagtegaal about his paper and the ongoing debate over King David and 10th-century b.c.e. Judah. The following interview has been edited for clarity.

Brent Nagtegaal (BN): Professor Garfinkel, welcome to Let the Stones Speak. Your latest academic paper was published in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology and is titled, “Early City Planning in the Kingdom of Judah: Khirbet Qeiyafa, Beth Shemesh 4, Tell en-Nasbeh, Khirbet ed-Dawwara and Lachish V.” It’s quite an academic title, but the evidence you present has significant implications on our understanding of the time period of kings David, Solomon and Rehoboam. In the paper, you explain how some scholars claim that Judah’s expansion—contrary to what the biblical record says—began in the ninth century, or even as late as the eighth century b.c.e. But as you explained, the data you have uncovered presents a different picture.

Prof. Yosef Garfinkel (YG): It’s a big question of how you make theories and prove theories in archaeology. Many scholars like to believe the theories that King David never existed, or that there was no kingdom at the time of David. These theories are wasteful and totally without evidence. As an archaeologist, my job is to go to the field and collect data at important archaeological sites, data that will illuminate what really happened in the 10th century b.c.e.

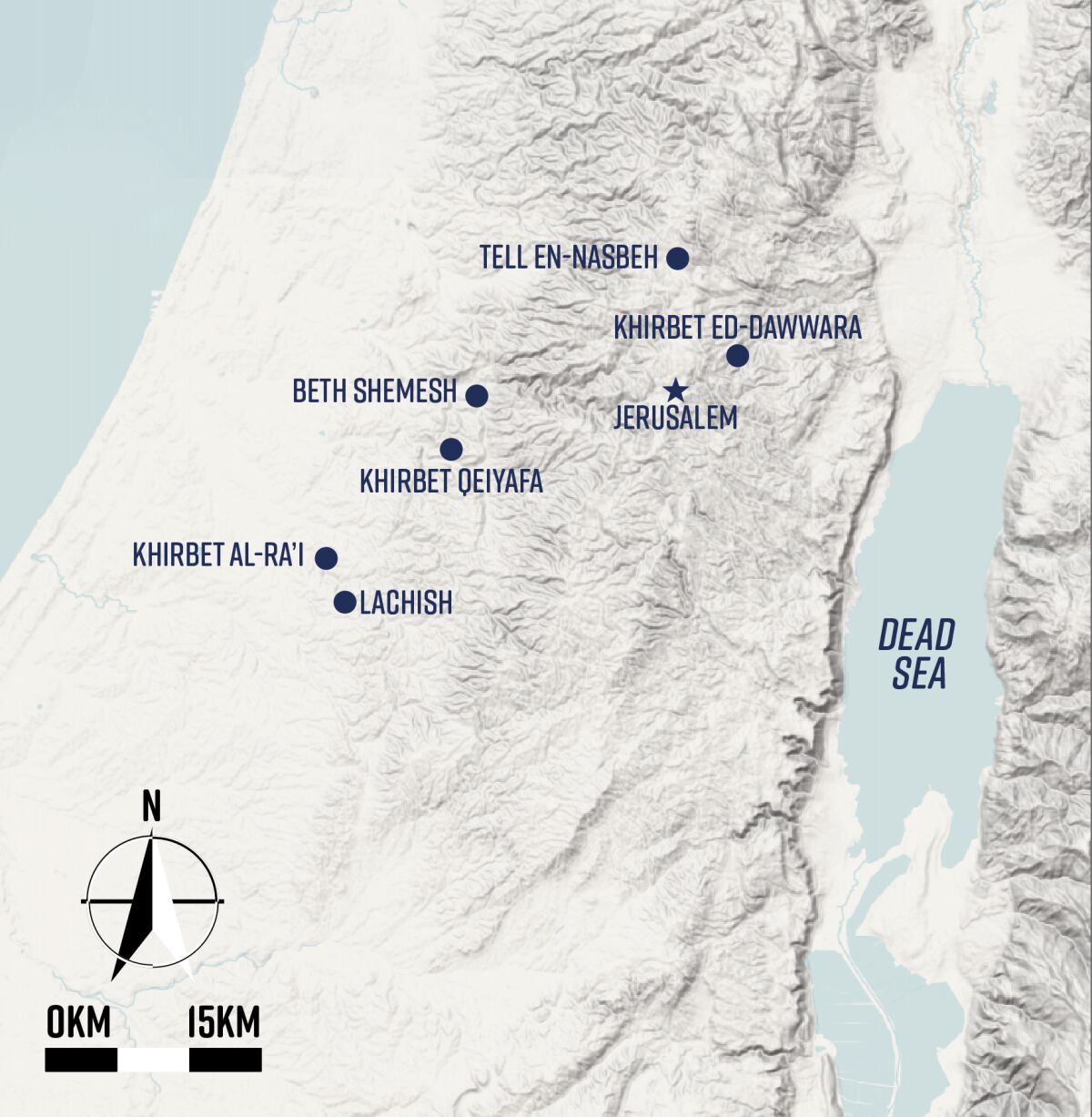

So far, I have excavated three sites that relate to the 10th century b.c.e. The first two sites are Khirbet Qeiyafa and Khirbet al-Ra’i [see map]. Our excavation at Khirbet Qeiyafa shows that it was a big fortified city. We’ve discovered inscriptions, public buildings, metal objects and other material that prove it’s really a very large and important city. Our dig at Khirbet al-Ra’i, on the other hand, has revealed a small village. We have only six rooms from the time of King David. So together we have a city and a village from the time of David [10th century b.c.e.].

What are the implications of what we have found at Khirbet Qeiyafa? First, Khirbet Qeiyafa was built with specific urban planning. We have a casemate city wall. This is a city wall that has two parallel walls. There’s an outer wall, an inner wall, and in between we have rooms. It is in a way a hollow city wall. It is not as strong as a solid city wall. But on the other hand, it’s cheaper and you can build it faster. So, there are advantages and disadvantages to this type of casemate city wall. But this is clearly what we have at Khirbet Qeiyafa. After doing further research, I discovered that we have similar urban planning in level four at Beth Shemesh.

BN: The excavation at Qeiyafa is important because you were able to use olive pits for radiometric dating to date the site to the early 10th century b.c.e., which is clearly the time period of King David. In your paper, you explain that the similarities between Beth Shemesh and Qeiyafa indicate that Beth Shemesh should also be dated to the 10th century b.c.e. So now we have two significant cities dated to the early 10th century b.c.e.?

YG: Beth Shemesh is a very important site and has been excavated a number of times. There was an early excavation between 1911–1912 by Duncan Mackenzie in the Turkish period. And then Elihu Grant excavated it during the British time (1928–1933). And from the 1990s onward, another expedition, led by Israeli archaeologists from Tel Aviv University Shlomo Bunimovitz and Tzvi Lederman, took place over 20 or more seasons.

During the British expedition, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, a casemate city wall was found. At the time, Grant and G. Ernest Wright wrote in their final reports that they found a casemate city wall like in Tel Beth Mirsim and Tell ed-Nasbeh. So here we have two other sites with the same pattern. In the 1950s and 1960s, archaeologists such as Nahman Avigad and W. F. Albright also wrote about accepting the presence of the casemate city wall at Beth Shemesh.

More recently, the site was excavated by archeologists who have a minimalistic view. Unfortunately, they completely ignored the earlier archaeology. Instead, they claimed that level four was a village, and even said it was a Canaanite village. But the pottery and the carbon dating of level four is exactly like Khirbet Qeiyafa. But they ignored the casemate city wall. Yet when you add the city wall to the pottery and the other carbon dating, what do you get? Another city like Khirbet Qeiyafa.

BN: The geography of Beth Shemesh and Qeiyafa is important too, right?

YG: Both of them are situated on the western border of the kingdom of Judah and on a main route leading from west to east.

BN: And valleys?

YG: Yes, you have the Valley of Elah, where Khirbet Qeiyafa is located, and the Valley of Sorek, where Beth Shemesh is located. So, both sites are on the border, where you have a main route, and both of them have the same urban planning.

We have two more sites that are in the northern part of Judah. First, there’s Tell en-Nasbeh. Some people identify this site with biblical Mizpeh, which is where the Prophet Samuel stayed. At Tell en-Nasbeh we also have a casemate city wall, which means the same urban planning. And where is this site? It is in Benjamin, in the northern border of the kingdom of Judah, on the main road leaving from the hill country, from Shechem and Samaria, into Jerusalem. So, it is the same pattern again, the same urban planning and the same location on the border. This is the third site.

The fourth site is Khirbet ed-Dawwara. This site was excavated more than 30 years ago. And again, it was published that this site was dated to the 12th to 10th century b.c.e. This would be the time period of the judges or maybe the first kings of Judah. Khirbet ed-Dawwara is a one-layer site. It is a small site, but there is urban planning and again you have casemate city walls and pottery just like that in Khirbet Qeiyafa. Remember, this site was excavated more than 30 years ago, before the dig at Qeiyafa, so the excavator didn’t fully understand what he was excavating. But here we have another stronghold, and this one is also on the border, on a route leading into the kingdom of Judah.

BN: In your paper you combine two important observations. You combine the dating of certain structures and layers with the urban planning that is associated with that specific dating. Why weren’t the earlier archaeologists stronger in dating these sites to the 10th century b.c.e.? Is it because they didn’t have the understanding of pottery that we now have?

YG: I think the main lack was Khirbet Qeiyafa, which was built and destroyed after 20 or 30 years [thus enabling the dating window to tighten].

BN: And when did you excavate [Qeiyafa]?

YG: We excavated from 2007 to 2013.

BN: So this is relatively recent in terms of excavation history.

YG: Yes, Khirbet Qeiyafa is like a biblical Pompeii from the time of David. It was built and destroyed within 20 or 30 years, so everything inside it is from the time of David. This is the first time we have a kind of fingerprint of what the material culture from the time of David looked like: how the pottery looked, how the metal objects looked, what was the religion, what were the animal bones, what was the economy, what was the international connection. This was not known before. When you excavate a site that existed for 300 or 400 years, it is very hard to find 25 or 30 years. So, it was a kind of luck. In antiquity, it was a big catastrophe that Khirbet Qeiyafa was destroyed so shortly after it was built. But from an archaeological point of view, it creates that biblical Pompeii from the time of David.

BN: We have a snapshot from 3,000 years ago. And what you have done is you have taken the finds from Khirbet Qeiyafa, which we know for certain are Davidic, and you have set them alongside these other cities. Then based on the similarities, you conclude that these other cities can also be dated to the 10th century b.c.e.

What about the urban planning? You mentioned casemate city walls. This is where two walls are parallel and perhaps rooms attached to them as well. Is the use of casemate walls Judean, Israelite or Philistine?

YG: There are no casemate city walls at any Philistine or Canaanite sites. Archaeology shows that casemate walls only existed in this period in Israel in sites that belong to the kingdom of Judah, and later to the kingdom of Israel. But there is one big difference between casemate walls in Judean cities and Israelite cities. In Judah, you have the casemate city wall, and you have the private houses abutting the city wall, and the casemate is part of the house. So, it means that the city wall is public, the houses are private and you combine public and private together. But when you study ancient cities in the kingdom of Israel, you have casemate city walls, but then you have a street and the houses starting after the street. So, the city wall is standing for itself. The urban planning between early Judah and the northern kingdom of Israel is clearly distinct, and this is important.

BN: Does the casemate wall style, architecture or urban planning go back before Iron iia, before 1000 bc.e.?

YG: Here in Israel, in the four sites I mentioned in my article, the casemate walls all date to around 1000 b.c.e. But we have casemate walls in Jordan that date a bit earlier. This too is quite interesting because tradition says that the Davidic family originated from Moab. So, maybe there was some influence from the area of Moab? Perhaps the casemate wall was not invented in Judah, but adopted from the Moabite people?

BN: Looking at these four cities, all of which can be dated to the 10th century b.c.e., you believe it is impossible to conclude that Judah expanded as late as the ninth century? What was happening in Judah in the 10th century? We’ve discussed that this was the time of David. Does the situation of these four distinct cities on the frontiers of Judah and the level of urban planning suggest the presence of a significant kingdom with a centralized government?

YG: Before David, in the time of the judges, we have only small villages. These were about 1,000 to 2,000 square meters, 1 dunam to 2 dunams (0.1 to .2 hectares). But now look at the new cities, these are 2 to 2.5 hectares. These urban centers are 20 to 25 times larger than the judges-era sites. It’s a real revolution. People at this time aren’t dwelling in small, tribal communities or extended families. They now live in a city. And in one city you can have four, five or 10 extended families. So it is a totally different way of social organization.

BN: Were these cities, in your opinion, created by a central authority or a merely a tribal authority?

YG: The fact that all of them have the same urban concept and that they are all sitting on the borders of the kingdom where a main route leads into Jerusalem, means it was a planned operation. You don’t build a city here, a city here, a city here, and then suddenly you have the border of the kingdom. I think before they put the first stone, there was a concept about how this thing should be organized.

BN: You discuss a fifth city in your paper, the city of Lachish. Where does Lachish fit? This city is dated a bit later than the others?

YG: As my understanding about the early 10th century b.c.e. grew, I decided to start investigating the latter part of the 10th century b.c.e. The biblical text says that King Rehoboam fortified 15 cities in Judah. One of these cities is Lachish. So, I decided to go to Lachish and see if we can find a city wall or what happened in Lachish in the latter part of the 10th century.

Lachish was first a big Canaanite city. It was destroyed in the time of the judges. Then the city was not inhabited for about 200 years, and some people believe it was more like 300 years. So, Lachish wasn’t inhabited during the second half of the 12th century, the 11th century and the first part of the 10th century. The last Canaanite city was level six, and after 200 years or so, they built a new level, which is level five. There is a big debate about level five. Is it a fortified city or merely a village? And what time period is it dated to exactly?

BN: Level five had been discovered before you started excavating Lachish, but the consensus was that it was not fortified. Is that right?

YG: There was debate about it, yes. The first excavator said it was built by kings David and Solomon and destroyed by Pharoah Shishak; and then level four was built by Rehoboam. This was one of the ideas of the first expedition. But if you look at all the different opinions, they vary from the early 10th century b.c.e. to the middle of the eighth century b.c.e.—250 years between the highest and lowest dating for level five at Lachish.

BN: This is the way archaeology was 30 years ago. But carbon dating has helped us get more accurate with our dating, right?

YG: I am not making new speculations. I said, “OK, let’s go and see what has happened.” We were the fourth expedition to Lachish. The three earlier expeditions worked in the southern, eastern and center regions of the site. Almost nobody examined the northeast side of Tel Lachish. But I thought that this was the most important part of the city. Why? It’s near the river. And the river is important because it gives you water and fertile land in the valley. This is also the main route leading from Ashkelon, the port city, to Hebron, in the hill country. Lachish is halfway between Ashkelon and Hebron. Caravans leaving the port city of Ashkelon could walk one day, stay in Lachish, do economic transactions, and then walk another day to Hebron. For this reason, I believed that this point close to the river would be the most important part of the city.

I wondered, “Maybe in the beginning, in the Iron Age, they built a smaller city” because the whole tel of Lachish is about 7½ hectares, which is rather big. I think it is logical that when they built the first Iron Age city, in the times of the kings of Judah, the first city was maybe three hectares or four hectares. And indeed, we excavated the northeast corner, and we found a new city wall that was not known before. Then we found houses abutting the city wall. We also found olive pits that we sent to be carbon-dated. These were dated to the latter part of the 10th century and the first part of the ninth century b.c.e.

Now we know that Lachish was not built by David and Solomon. It was built and used by Rehoboam. This fits the biblical tradition that Rehoboam fortified 15 cities in Judah, including Lachish.

If you look at the earlier fortified cities with casemate city walls, they are located up to a one-day walk from Jerusalem. Khirbet Qeiyafa and Beth Shemesh are a one-day walk. Tell en-Nasbeh and Khirbet ed-Dawwara are a half-a-day walk. But Lachish is much further away; it’s a two-day walk from Jerusalem. Under Rehoboam, the territory was expanded.

It’s also interesting to consider sites further to the south in the Be’er-Sheva valley, like Arad and Be’er-Sheva. In the 10th century, these sites were unfortified villages. But later in the middle part of the ninth century, they became fortified. The kingdom of Judah expanded over time. It didn’t happen suddenly.

BN: You come to these conclusions separate from the Bible. However, the Bible shows that David initially ruled from Hebron. This indicates that Judah was already established 30 kilometers south of Jerusalem at the start of the 10th century. So, according to your model of expansion, would you expect to find similar 10th-century construction in ancient Hebron.

YG: I am trying to build a scenario on archaeological data. It is independent. I look at the facts, a city wall, a city situated on a geographical border, the main routes leading into the kingdom. These are fixed and incontestable. And it’s evident that they all belonged to the same wave of urbanism.

According to the carbon dating from Khirbet Qeiyafa and Beth Shemesh, they are from the earlier part of the 10th century b.c.e. The other sites where we don’t have carbon dating because they were excavated much earlier, have the same pottery or the same urban planning. And then Lachish is different. When we were excavating level five at Lachish, the pottery is not like Qeiyafa. It is different. And not only the local pottery, also imported pottery from Cyprus. In Khirbet Qeiyafa, we have an earlier type of Cypriot vessel, which is decorated with “black on white.” And then later in Lachish, in level five, we have “black on red.” So the Cypriot pottery is earlier in Qeiyafa according to Cypriot archaeology, and later in Lachish.

The same happened with the local pottery because what we have in Khirbet Qeiyafa is the beginning of a new tradition, which is where you have red slip and irregular hand burnishing. In Khirbet Qeiyafa, it is very rare, but it is already there. When you go to Lachish level five, it is very common. So, you can see the development over time in the local pottery and the exported pottery from Cyprus.

BN: Have you studied any other tels or mounds? You have obviously gone back to see what they found at Beth Shemesh and these other sites after they were excavated. You didn’t excavate them. You looked through their discoveries, their pottery. Are there any other cities with this 10th-century pottery on the periphery of Judah?

YG: I heard that they have an excavation now at Tel Burna, which is between Qeiyafa and Lachish; it also has early 10th-century b.c.e. pottery. But I don’t know if it was fortified or not fortified. I haven’t yet seen a meaningful report about these discoveries. But I am sure that there will be more sites.

Personally, I don’t believe in exceptional discoveries because people behave in a pattern. The goal of archaeology is to find the pattern. When you find the first city, you don’t have a pattern yet because it is just one. But after 10, 20 or 30 years, you can have the second example. And after another 10 or 20 years, you might have the third, the fourth and the fifth. And I think today we have enough examples that are pointing to a pattern. And this is what I think is so important in this article.

So far, I have published all the results of Khirbet Qeiyafa, but it was only one site. From one site, you don’t have a kingdom. And now because it was possible to see the pattern also in four other sites, you really get a nice picture.

BN: I think it is just amazing because people know that archaeology has gone on for a long time. A lot of digging has gone on over the past 100 years here in the land of Israel. And yet here we are in 2023, and we have this dramatic discovery of a pattern, a model that shows Judah was established in the 10th century b.c.e. Do you feel like there is going to be pushback from some archaeologists?

YG: No, I’ve never worried about what other scholars might say. I am always saying, “We have fresh data. They have a collapsed theory.” That’s what has happened time and again. But I also think that sometimes people don’t understand how archaeology works. Do you think it is possible for me to go to Washington, D.C., excavate and find the man Abraham Lincoln? It’s not possible. So in a way, it is not possible to find David. But what do we see? We see the transition from a tribal community into a state, and we can see that it happened around 1000 b.c.e., the time of David. But we cannot have David himself. It is not possible in archaeology to find one person. And the same, by the way, with Solomon. You cannot find Solomon. But we have traditions that in the time of Solomon there were intensive royal activities—building activities in Jerusalem, like a palace and a temple. And in Khirbet Qeiyafa, we have a building model, an elaborate model, which has the same architectural features that appear in the Bible in relating to the building activities of Solomon. So, you can see that this type of royal building was known in Jerusalem at the time of David and Solomon.

BN: So you might not have found the individuals themselves, but you have found evidence that the state existed at the same time that the biblical record puts David and Solomon on the scene. Thanks very much for explaining this to us.

YG: You’re most welcome.