“As the music is, so are the people of the country,” says a Turkish proverb. Confucius said, “If one should desire to know whether a kingdom is well governed, … the quality of its music will furnish the answer.”

One of the clearest lenses into any civilization is through an exploration of its musical culture. The ancient Hebrews—called by some “born musicians”—are no exception. Yet few give this real consideration.

Because music is an aurally based art form, and much evaporates from consciousness if those sounds are not codified or recorded in any detailed way, we can resign to the fact that we’ll never know much about ancient music.

Putting what the actual music sounded like aside, however, we see that music was highly valued by ancient Israel, from religious to secular spheres. It was not considered some diversion to merely gratify the senses but was believed to contain spiritual properties that elevated mankind to a higher plane and offered insight into physical and spiritual realms like nothing else could.

The art form was especially cherished by its biblical authors, many of whom possessed musical prowess and wrote of it intelligently—from Moses to Ezra. Its mention in the royal histories reinforces the commendation given righteous kings, and the sheer square footage and resources dedicated to the art form inside the temple is an obvious testament to its significance.

In terms of helping us understand ancient Israel through a musical perspective, two characteristics from the biblical record stand out. These reinforce the same virtues the nation as a whole possessed: Its music was both highly advanced and had a profound impact on surrounding nations.

Challenging Evolutionary Theory

We tend to view ancient music as “primitive,” but this is a fundamentally evolutionary view. I’m reminded of my college music-history professor, who consistently challenged any student who wrote or said that music “advanced” throughout modern history—in the sense that Ludwig Beethoven was more advanced than G. F. Handel or that Richard Strauss was more advanced than Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Change and development did not necessarily mean better or more sophisticated. After all, who could argue that a Johann Sebastian Bach cantata is somehow more primitive than a Gustav Mahler symphony?

Yes, instrumental craftsmanship improved over time, mainly in the sense that instruments had more range dynamically and pitch-wise. But the harmonic order of a composition 300 years ago would not necessarily be more primitive than one of our day—just as the prime numbers in mathematics back then are the same numbers today. An evolutionary view of music history leads us to believe that music originated clumsily and serendipitously from prehistoric brutes—vocal music coming from prolonged grunts of early human-like beings and instrumental music developing accidentally from a hunter becoming fascinated with how his bow twanged after an arrow was unleashed.

Even many professed Bible scholars, though they may reject evolutionists’ happy-accident theory, believe music originated with a descendant of Cain named Jubal (Genesis 4:21), that humanity lived several centuries before we finally stumbled onto music, and that the Creator Himself didn’t give the first humans any understanding of it. (In fact, what Jubal was doing was a clear misuse of music, per the original Hebrew.)

Man did not start with a one-, three- or five-note scale and slowly decide that seven tones work better mathematically. Same with, say, the strings on a harp.

Excavations in the 1920s at Megiddo lent support to this when 20 floor stones dating from 3300 to 3000 b.c.e. were uncovered. The carvings on one of them depicted a female harpist with a triangular-shaped instrument having eight or nine strings—quite an advanced instrument. Archaeologically, this harp appears out of nowhere, especially if it merely “evolved” from a one-stringed instrument.

Could something this advanced have existed in Eden? Isaiah 51:3 implies “the voice of melody” was in Eden, and the Hebrew word for melody comes from the root meaning “to pluck.” Were there stringed instruments there? Psalm 92 is inscribed “A Psalm, a Song. For the sabbath day.” The Targum reads: “A psalm and song which Adam uttered on the Sabbath day.” This doesn’t necessarily ascribe authorship to Adam, just the performance. This psalm also mentions stringed instruments.

Highly Advanced

Traveling chronologically through the Bible, we soon arrive at the nation of Israel. Moses said God had given them special wisdom, by virtue of them having His laws (Deuteronomy 4:5-8). The author of Psalm 119 uttered a similar sentiment (verses 98-100).

In the Anchor Bible, Hebrew poetry expert Mitchell Dahood discussed the “highly sophisticated” nature of the psalms and concluded, “The poets’ consistency of metaphor and subtlety of wordplay bespeak a literary skill surprising in a people recently arrived from the desert and supposedly possessing only a rudimentary culture” (emphasis added throughout).

Truly, when we explore Israel’s music in the biblical record, we find evidence that it was highly advanced melodically and harmonically.

One indication is found in the Hebrew word sheminith—a word that remained untranslated in both the Jewish Publication Society (jps) Tanakh and the Authorized Version of the Bible. It is found in two of the musically enigmatic psalm inscriptions (Psalm 6 and 12). Some suggest sheminith was an eight-stringed instrument, but an instrument of this kind is noticeably absent from other passages of the Bible that list instruments of the Hebrew orchestra. Many scholars agree that this is a reference to the musically universal interval known as the octave.

In English, the word itself implies an interval (distance between two pitches) of an eighth. On a modern piano, if you find a C and call that “one,” then white-key number “eight” (either higher or lower) is also a C—and played together, they sound a lot alike. The reason is that the frequency of the higher note’s vibration is exactly twice as fast as the lower one.

The use of this interval in music is common and transcends all cultures. If a father and his young son sing the same melody in unison, the father is probably singing the same notes in a lower register whether they call it an octave or not.

1 Chronicles 15:21 uses this word to describe men who played “with harps on the Sheminith, to lead.” The Hebrew likely implies that these men played their harps or sang the melody an octave higher or lower to make their pitches stand out among the other instruments in the ensemble—composers and arrangers know the power of doubling things with the octave. Their eighth would be the “lead” part of the aural texture.

What is interesting about the word sheminith is that it indicates something about the Hebrews’ scale system: The fact that the first note and the eighth note were that perfect and common interval indicates that there were seven notes leading from the lower to the upper frequency. The Hebrews were using a seven-tone, or a heptatonic, scale.

Evolutionists would have us believe that mankind started as savages with a more primitive scale system—perhaps the pentatonic scale (a series of five pitches). But many credible musicological sources contradict this idea. One of them, the New Oxford History of Music, states that the pentatonic scale cannot be considered older than the six- or seven-degree diatonic scale

commonly used in Western music.

In his 1893 book Primitive Music, Richard Wallaschek wrote: “[A] succession of tones exactly corresponding to our diatonic scale (or part of it) occurs in instruments in the Stone Age, and … we have no reason to conclude that a period of pentatonic scales necessarily preceded the period of heptatonic ones.”

In her argument that the Hebrews used a heptatonic scale, Suzanne Haïk-Vantoura established first how in 1968, Babylonian cuneiform was discovered that “unequivocally” attested to the “total similarity between the Babylonian scale … and our own C-major scale.” The facts “witness to a system (graphically confirmed) based upon diatonic modes of seven degrees …” (The Music of the Bible Revealed).

In his book This Is Your Brain on Music, neuroscientist Daniel J. Levitin discusses experiments that have “shown that young children, as well as adults, are better able to learn and memorize melodies that are drawn from scales that contain unequal distances such as this” (i.e. the seven-tone scale based on its system of whole steps and half steps).

An innate feature of this scale system is something akin to a gravitational pull to one of the seven notes—what musicians call the “tonic,” or “home” (or, as Julie Andrews sang in The Sound of Music, something that “brings us back to ‘do’”).

What about the simultaneous use of more than one pitch—i.e. harmony? Evolutionary and primitivist theories would have us suppose that man stumbled around for thousands of years playing or singing one note at a time, and not until the “organum” of the Middle Ages were we to discover the richness that comes from the complex layering of pitches.

Though the Bible makes no explicit mention of “harmony,” it must have existed in the Hebrew musical culture. The biblical record shows groups of people—men and women (different vocal ranges)—singing together. It discusses assorted musical instruments playing together at the same time. That these musicians would play or sing together and never consider doing something different yet complementary to the melodic line is absurd. That a culture so exceptional in stringed instruments would never think to pluck more than one string at a time (a different, complementary string) is ludicrous.

2 Chronicles 5:12-14 describe the scene at the dedication of the first temple under King Solomon—Levites “with cymbals and psalteries and harps” plus “a hundred and twenty priests sounding with trumpets.” The chronicler records that “the trumpeters and singers were as one, to make one sound to be heard in praising and thanking the Lord; and … they lifted up their voice with the trumpets and cymbals and instruments of music ….”

Are we to believe that all those instrumentalists were playing the same notes at the same time? That everything was in unison? That the trumpeters, capable of producing a series of pitches based on lip tension, all decided to play identical notes? Some may argue that “as one, to make one sound” implies monophony, but objective study shows that this is not a comment on the musical texture but high praise of its performance. The ensembles were truly together. Their performance was rhythmically precise and in tune. We would say the same about a fine symphony orchestra today: They were as one—despite all the different notes and parts, they played perfectly together and in tune!

One of the most pleasing harmonies to the human ear, and one upon which the majority of standard repertoire is based, is the third. On the piano, if you play a white note and call that “one,” then count up or down to three, and you play note “one” along with note “three,” that is an interval of a third.

Carl Engel wrote in 1864: “Harmony is not so artificial an invention as has often been asserted. The susceptibility for it is innate in man, and soon becomes manifest wherever music has been developed to any extent. Children of the tenderest age have been known to evince delight in hearing thirds and other consonant intervals struck on the pianoforte; and it is a well-ascertained fact that with several savage nations the occasional employment of similar intervals combined did not originate … with European music, but was entirely their own invention” (The Music of the Most Ancient Nations, Particularly of the Assyrians).

If more primitive cultures were using the third, then certainly the musically adept Hebrews would have been too. Curt Sachs believed that secular music was using thirds and harmony throughout history, and that is why West European music flourished so rapidly after the yoke of plainchant was broken.

In Music in Western Civilization, Paul Henry Lang documented how Giraldus Cambrensis (1147–1220) discussed the harmonic practices of the British Isles. Harmony, he said, was so common that “even the children sang in the same fashion, and it was quite unusual to hear a single melody sung by one voice. … The Anglo-Saxon Bishop Aldhelm, at the end of the seventh century, and Johannes Scotus Erigena (ninth century), seem to allude to ‘harmony’ as the simultaneous sounding of tones. Finally, the first records of actual music for more than one voice also come from England.”

How fascinating that there exists a linguistic link between Britain and the Hebrews in this regard. The third letter of the Hebrew alphabet (and the numeral three) is gimel, or gymel. This word was actually the term used in England to describe singing in parts (the most common interval in such layering being the third).

Haïk-Vantoura masterfully summed up the highly advanced nature of Hebrew music by saying that it was “just as solid,” if not more so, than “that of the great and powerful neighboring peoples who were Israel’s contemporaries; its musical resources effectively served the authentic and eminently human faith which made use of them.” She wrote, “All this persuades us that there is no reason to imagine an ultra-primitive kind of music. … The texts of the Psalms of David and the inspired singers have always been unanimously admired. Why then would the music to which they were sung not have been stirring and beautiful, and accessible, just as the text of the Psalms have remained?”

Impactful

A testament to the advanced and rich nature of ancient Hebrew music is seen in the impact it had on surrounding peoples. This is particularly evident in Scripture and secular sources when showing how attractive Hebrew music was to neighboring nations.

Moses’s words of Deuteronomy 4:6 rang true: “[T]his is your wisdom and your understanding in the sight of the peoples, that, when they hear all these statutes, shall say: ‘Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people.’”

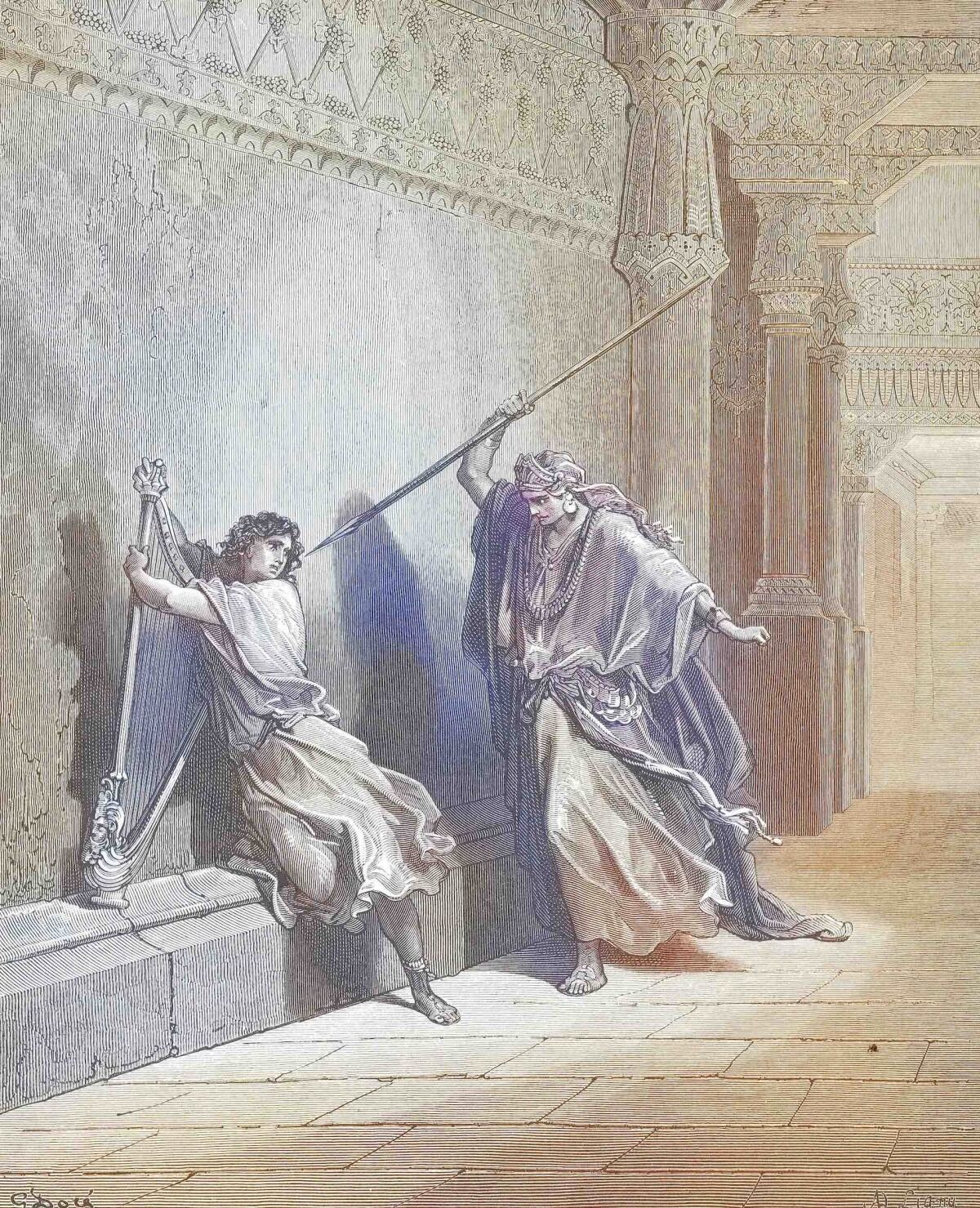

During the reign of King Saul, while David was on the run for his life, we see an interesting exchange in Philistine territory. Before we read this, consider the song uttered by “the women” in 1 Samuel 18. Not only was David a musician himself, he was the subject of a song honoring his triumph over Goliath: “And the women sang one to another in their play, and said: Saul hath slain his thousands, And David his ten thousands” (verse 7).

So when David “went to Achish the king of Gath,” the chronicler records that “the servants of Achish said unto him: ‘Is not this David the king of the land? Did they not sing one to another of him in dances, saying: Saul hath slain his thousands, And David his ten thousands?’” (1 Samuel 21:11-12).

The king of Gath knew the lyrics of the song, how it was sung (“one to another”), and how it was performed (“in dances”—compare 1 Samuel 18:6). The same question was asked later by the Philistines (1 Samuel 29:5). Part of David’s renown to the neighboring peoples was a popular song about him! In our 21st-century world, it is difficult to appreciate how extraordinary this is, for a song to be known miles away in neighboring lands in a time without mass media. Music from Israel was somehow being exported to neighboring lands.

It stands to reason Israel’s musical fame would have only increased when David was king, one known as the “sweet singer of Israel” (2 Samuel 23:1). Music played a prominent role in his reign, a time when he had the respect of neighboring rulers like Hiram of Tyre. For his procession to return the ark of the covenant to Jerusalem, 1 Chronicles 15 numbers 870 priests and Levites in the tuneful parade. By the end of his life, he proclaimed that 4,000 Levites played instruments he had made (1 Chronicles 23:5). He composed the majority of the book of Psalms: 75 psalms have his name in the inscription, and by considering other passages (even some in the New Testament), it’s clear he wrote at least a dozen more.

Like his father, Solomon was a composer-king whose influence was far-reaching. His coronation inspired a musical celebration recorded as having a seismic impact on the land (1 Kings 1:39-40). We already read about the unmatched musical performance at the dedication of the first temple. 1 Kings 5:12 (1 Kings 4:32 in the King James Version) says Solomon wrote 1,005 songs. In modern musicological terms, no music historian would ignore that prolific a composer: We study Antonio Vivaldi’s 500 concerti, Domenico Scarlatti’s 550 keyboard sonatas and Franz Schubert’s 600 lieder. Not only did Solomon write the “song of songs” (Song of Solomon 1:1)—implying “the most beautiful song”—music is a common topic throughout his proverbs and an ever more frequent subject in his reflective book of Ecclesiastes (e.g. Ecclesiastes 2:8; 3:4; 7:5; 10:11; 12:4). His vast trade networks brought many goods from Egypt (2 Chronicles 9:21-28); secular sources say this included over 1,000 musical instruments.

It was through the temple complex, however, that Solomon’s culture had its greatest impact regionally. It fulfilled his father’s desire that it be “of fame and of glory throughout all countries” (1 Chronicles 22:5).

The visit of the Queen of Sheba is a vivid illustration of how rulers of that day responded. 1 Kings 10:1-10 show her reaction was to not just the edifice itself but also its cultural activities. The result of this visit was a donation to the tune of roughly $130 million by today’s standards, plus spices and precious stones.

The verses that follow show another trade affiliation related to the musical culture: “And the king made of the sandal-wood pillars for the house of the Lord, and for the king’s house, harps also and psalteries for the singers; there came no such sandal-wood, nor was seen, unto this day” (verse 12). He had instruments crafted out of this precious wood of his day. 2 Chronicles 9:11, in speaking about these instruments, adds, “and there were none such seen before in the land of Judah.”

Another example of Israel’s musical impact on surrounding cultures can be found by harmonizing secular and biblical history in the time of King Hezekiah. When this king feared an invasion by Sennacherib, he sent the Assyrian king treasures from the temple and treasures from the king’s palace (see 2 Kings 18:14-16). Sennacherib’s relief shows that this included some of his own court musicians as part of the tribute. Musicians were indeed considered “treasures” of the king’s house!

In Music in Ancient Israel, Alfred Sendrey wrote that the “artistry of these singers” must have been exquisite “if Sennacherib valued them higher than the pillage and plundering of the enemy’s conquered capital city.”

Later, after Jerusalem had been plundered and taken to Babylon, we read an interesting demand on the Jewish captives. A psalmist recounted this history “[b]y the rivers of Babylon” (Psalm 137:1), where they hung their harps on willows (verse 2). Verse 3 states: “For there they that led us captive asked of us words of song, And our tormentors asked of us mirth: ‘Sing us one of the songs of Zion.’” These were a remarkable people. Not only did they claim to have “the Lord’s song” (verse 4), the Babylonian captors wanted the Jews to sing Zion’s songs. This nation was renowned for its musical achievements, and their music was an enviable commodity!

Resilient Traditions

Under the light of biblical music history, we see an incredible civilization. The ancient Hebrews not only valued music, the biblical record (corroborated by secular sources) shows they cultivated it for centuries in an incomparable way. It was so ensconced in Hebrew society that it survived through the darkest of periods—even the 70-year hanging-harps-on-the-willow hiatus in Babylon, as the books of Ezra and Nehemiah bear out.

Before that, rich musical instruction emerged in the days of Samuel after the dark centuries under the judges. There was David’s rather prolific output while on the run from Saul. Later, the temple musical traditions thrived despite the six-year tyranny under the usurper Athaliah. Truly, the Hebrews were a people who reflected the characteristics of their great Creator and Artist. As Psalm 22:4 states, it was as though God Himself was “enthroned upon the praises of Israel.”