A study published in October 2022 by The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology has concluded that previously discovered Egyptian branding irons were likely used for human slaves instead of livestock.

A series of 10 branding irons, as well as ancient Egyptian texts, carvings and paintings discussing slavery, were analyzed, and it was determined that such tools were used for marking human skin, rather than animals. These particular bronze branding irons date between 1292 and 656 b.c.e., used during Egypt’s 19th to 25th dynasties.

Branding cattle and horses requires a branding iron that is about 4 inches (10.6 centimeters) long, so that as the calf grows, the scar will remain legible. The branding irons analyzed were a third of this size, hence far too small for large cattle.

The paper’s author, Egyptologist Ella Karev, told Live Science, “They are so small that it precludes them from being used on cattle or horses.” She continued, “I’m not excluding the possibility, but we have no evidence of small animals like goats being branded, and there is so much other evidence of humans being branded.”

Slavery in Egypt is undisputed, both in the biblical and secular accounts. Some claim, however, that slavery in Egypt was not overly oppressive and that the Bible exaggerates the account of the Israelites in bondage. However, what studies like this reveal is the extreme harshness of slavery in Egyptian society, as well as how slaves were viewed by the population.

Karev continued, “The identification of these marks as brands emphasizes the dehumanization of these enslaved persons and implies that their status was on par with other property such as cattle.”

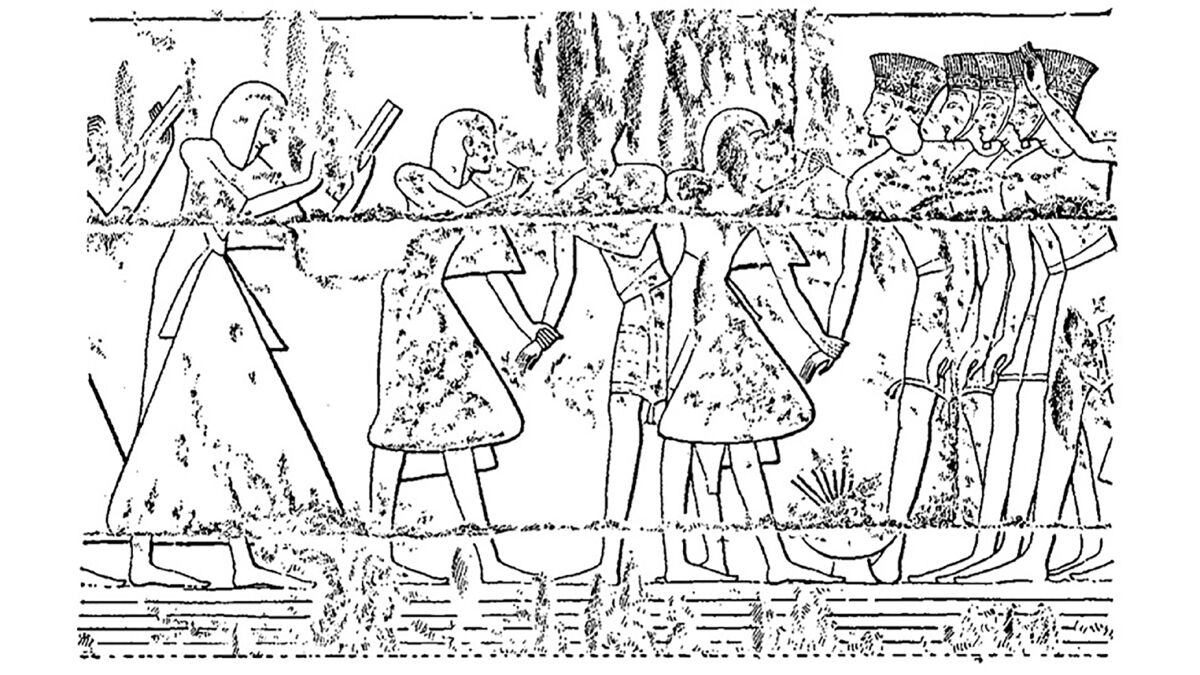

Researchers formerly assumed that Egyptian writings and depictions of slaves with markings were solely referencing tattoos, as this was also a common practice at the time. (You can read more about that here.) Tattoos had more of a religious and decorative purpose in ancient Egypt, whereas branding slaves provided a clear, distinguishable mark that placed humans on the level of animals in the eyes of Egyptians.

But tattooing slaves en masse would have been time-consuming and tedious.

Karev states, “Practically speaking, ‘hand-poking’ a tattoo [without a modern tattoo machine] takes quite a lot of time and skill—and if you’re doing that on a large scale, it’s not easily replicable. It would make much more sense for this to be branding.”

It isn’t a stretch to believe that Egypt applied this branding practice to the Israelites during their captivity. (Read more about the archaeological evidence for that here). Massive groups of slaves were likely branded, subjugated and traded harshly. Perhaps they were branded based on their role or their “owners.”

Exodus 1:12-14 reads, “But the more they afflicted them, the more they multiplied and the more they spread abroad. And they were adread because of the children of Israel. And the Egyptians made the children of Israel to serve with rigour. And they made their lives bitter with hard service, in mortar and in brick, and in all manner of service in the field; in all their service, wherein they made them serve with rigour.” Indeed, the Egyptian kingdom was literally built upon the backs of slaves.

But tragically, this brutal practice of branding or tattooing slaves is not such a distant memory—even in our modern, so-called “enlightened” age.