Here in Israel, the book of Esther is on people’s minds at this time of year as they celebrate Purim, the holiday marking the saving of the Persian Jews from a genocide led by the wicked Haman (Esther 9:26-32).

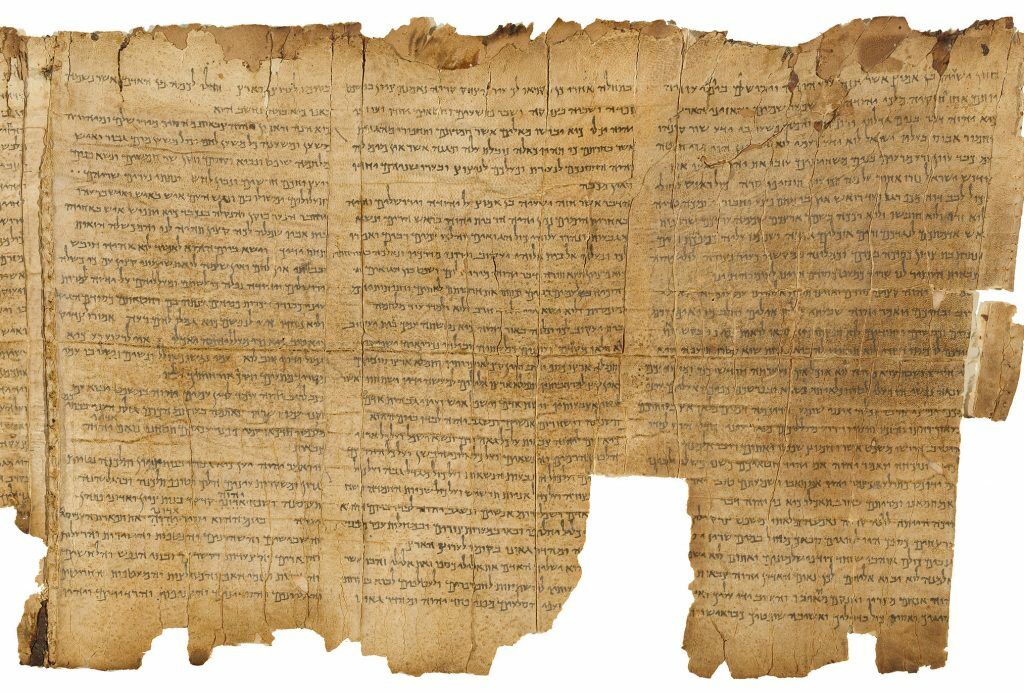

The book of Esther is notable among the biblical canon in that it was one of the last books to be written and the last to be canonized. There are numerous peculiarities about this book of the Bible—and it is common knowledge that among the Dead Sea Scrolls (a trove of fragmentary manuscripts dating variously from the third century b.c.e. to the first century c.e.), this is the only biblical book entirely missing.

This has, in part, led to various speculations about the authenticity of the Esther account, including perceived “difficulties” for its original inclusion into the biblical canon. Bible.org’s “Introduction to Esther” highlights four such points of “contention” about the book of Esther:

1) Probably because it does not mention (a.) any name of God, (b.) the temple, (c.) the Law of Moses, (d.) sacrifice (the cultus of Israel), (e.) Jerusalem, (f.) prayer (although it is implied).

2) The Dead Sea Scrolls have copies (in whole or part) of every book of the Hebrew Bible except Esther.

3) The book of Esther, like Ruth, is not quoted in the New Testament.

4) It has gotten mixed reviews from [early Bible] commentators.

Most of these points are moot. The reason for nearly all of point 1 is obvious: The book of Esther takes place in a Persian community, centered particularly around Susa. The Jewish people had been deported from Judah and Jerusalem some 100 years earlier after the destruction of the city and temple. For point 3, the logic should also disqualify the book of Ruth (as well as Ecclesiastes and Song of Solomon, works likewise not quoted in the New Testament). This assertion about Esther is debatable, though—and there is even significant opinion that John 5:1 refers to “no other than the Feast of Purim”! (Note also that the Jewish historian Josephus, of the same first century c.e., describes the Esther account at length in Antiquities 11.6.)

And regarding point 4, “mixed reviews” can be found on anything. Regarding the book of Esther, for example, the central figure of the Protestant Reformation—Martin Luther—believed it should be “excluded from the canon because it was too Judaistic” (note that he also rejected certain New Testament books, like the Book of Revelation); on the other hand, the famous Jewish medieval commentator Maimonides believed Esther was “next to the Law of Moses in importance.”

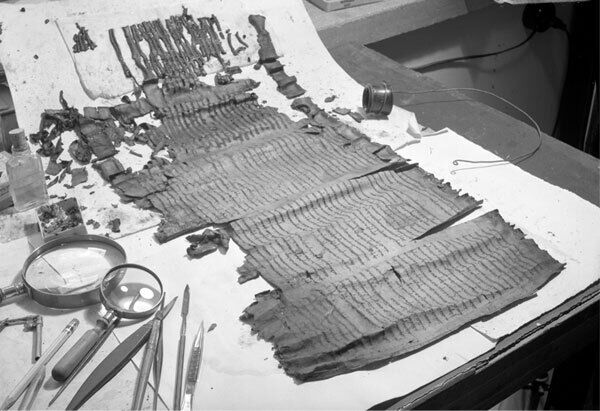

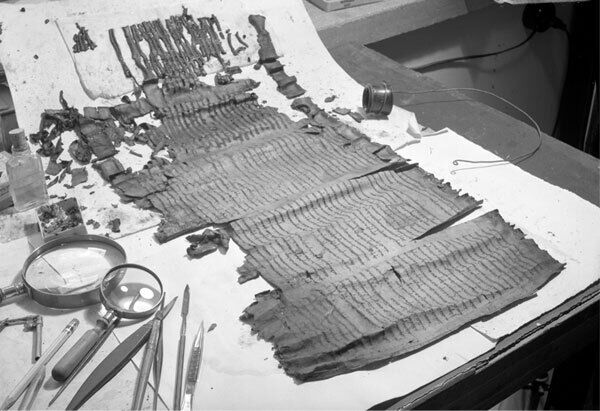

But what about point 2? “The Dead Sea Scrolls have copies (in whole or part) of every book of the Hebrew Bible except Esther.” This is an often-cited “fact.” The Dead Sea Scrolls, an enormous trove of preserved and partially-preserved works, contains a total of some 800 scrolls; roughly 30 percent constitute to biblical texts. As Stephen Curto wrote in “Should She Stay or Should She Go? The Canonicity of Esther”:

[This] objection, that Esther is absent from the Dead Sea Scrolls, is a more worthwhile argument for those who oppose canonicity. The Dead Sea Scrolls is easily the most significant archaeological discovery of the past century, and possibly millennium. It is the most comprehensive collection of Old Testament manuscripts discovered to date. … There were fragments from every single Old Testament book found at Qumran, the location of the discovery, except Esther.

Thus, a theory has prevailed that Esther had not yet, at this late turn-of-the-millennium period (and centuries after the events it describes), officially entered the biblical canon, due in large part to a lack of trust in its authenticity.

One recourse of explanation in defense of Esther, however, is that numerous Dead Sea Scroll fragments—charred, disintegrated and faded—are entirely unreadable, and thus may have contained Esther material after all. There is also the inferiority of the argument of silence, as Curto noted: Just because something hasn’t been discovered, doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. (The same position has been held for the likes of biblical kings David and Belshazzar and, rather embarrassingly, even for the existence of the Hittite empire—until they were later discovered by archaeologists.)

Another explanation is that the book of Esther is in itself a small work, which would leave less of a “footprint” among the Dead Sea Scrolls. (Technically, the same could be said of the book of Nehemiah, a work of similar length also not found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. However, the reason this book is not similarly counted is because Ezra and Nehemiah originally were combined as a single text, and fragments of text within the Ezra portion have been found.) Another explanation is that, since the book of Esther does not contain the name of God, it did not need to be ritually preserved or buried (a traditional Jewish practice derived from Deuteronomy 12:3-4, to prevent damage to the “name of God”).

Finally, there is an “elephant in the room”—the Qumran community were themselves designated as a group of “religious wackos,” monastic desert pariahs from the central Jewish communities and sects, with numerous fringe beliefs (including an entirely different solar calendar); thus, they should not be seen as representative, consequential preservers of scripture or doctrine.

These are all valid points—but what if none of them are necessary? For despite the lack of direct evidence of an Esther scroll itself, certain other manuscript discoveries from Qumran do indicate that the community was not only aware of, but was entirely conversant with, the book of Esther.

1QapGen

The rather mundanely-named Dead Sea Scroll fragments 1QapGen and 4QprEsth ar constitute apocryphal, late Aramaic fragments among the Dead Sea Scrolls. 1QapGen (the “Genesis Apocryphon”) expounds on an incident at Pharaoh’s court involving Abraham and Sarah, using remarkably similar language to the account of Esther and Mordecai in the court of Ahaseurus. And 4QprEsth ar constitutes six fragment clusters relating to some relatively obscure apocryphal story set in the Persian period, with like linguistic similarities to the Book of Esther.

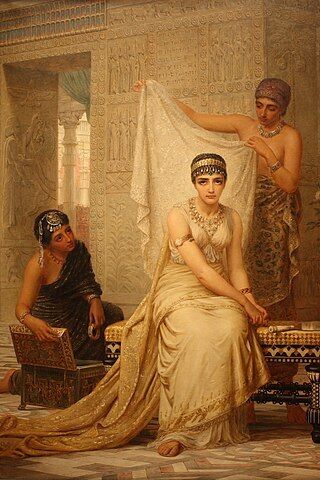

1QapGen was proposed by its researcher, J. Finkel, to be evidence of the pre-existence of, and the author’s dependence on, the book of Esther (published in his article “The Author of the Genesis Apocryphon Knew the Book of Esther (in Hebrew)”). For example, 1QapGen 20:6-7 describe Sarah’s beauty, as follows: “[A]nd all maidens and all brides that enter under the wedding canopy are not fairer than she. And above all women is she lovely and higher in her beauty than that of them all.” This is a parallel to Esther 2: “[T]hus came every maiden unto the king …. And the king loved Esther above all the women, and she obtained grace and favour in his sight more than all the virgins” (verses 13, 17; King James Version).

Further on in 1QapGen 20:30, we read: “[A]nd the king swore to me with an oath that cannot be changed.” This parallels Esther 8:8: “[F]or the writing which is written in the king’s name, and sealed with the king’s ring, may no man reverse.”

The similarities compound. In the Aramaic 1QapGen, “בוץ וארגנואן” is mentioned; properly, this is a very specific term referring to a fine linen of purple (as explained in Shemarayahu Talmon’s 1995 article “Was the Book of Esther Known at Qumran?”). The Aramaic account records this material was given by the ruler to Abraham when he was sent forth from the court. This word combination is only found, among the books of the Bible, in the book of Esther, and in two places—Esther 1:6 and 8:15—describing royal apparel specifically bequeathed by the king to Mordecai when he was sent forth from the court (with the exact Hebrew equivalent “בוץ וארגמן”)! What’s more, in the veritable ocean of rabbinic literature, this word combination is again only found in commentaries relating to Esther!

Individually, each of these parallels make for interesting speculation. Collectively, however, they speak to Finkel’s only logical conclusion, that the author of the apocryphal Dead Sea scroll Qumran 1QapGen must have had a knowledge of and drew from the existing book of Esther.

4QprEsth ar

Research of the small Aramaic 4QprEsth ar fragments was conducted by J. T. Milik and published in 1992. Likewise, similarities were noted between the biblical text of Esther and this enigmatic work, indicating a connection or understanding between the two.

4QprEsth ard ii 6 reads: “[H]is wickedness will return on his own [head …].” This parallels Esther 9:25: “[H]is wicked device, which he had devised against the Jews, should return upon his own head.”

4QprEsth ard ii 3 describes honor being given to a queen, in the form of a “[royal …] crown of go[ld upon] her [he]ad.” This parallels Esther 2:17: “[H]e set the royal crown upon her head.”

4QprEsth ara 3-5 reads, in part: “At that same hour the temper of the king was stretched [… the bo]oks of his father should be read to him and among the books was found a scroll … it was found written within ….” This parallels Esther 6:1-2: “On that night could not the king sleep; and he commanded to bring the book of records of the chronicles, and they were read before the king. And it was found written …”

4QprEsth ard I iv 2-3 describe: “A man of Judah, one of the nobles of Benjam[in …] an exile ….” This parallels Esther 2:5-6: “[A] certain Jew … a Benjamite, who had been carried away from Jerusalem with the captives.” And in a line of text near this reference, Milik proposes the following reconstruction: “[אנה אס[תר” “[… as for] me, Es[ther].”

But Wait—There’s More

Besides the parallels in 1QapGen and 4QprEsth ar, Shemarayahu Talmon (in his aforementioned article) offers numerous additional examples to show the Qumran community’s familiarity with the book of Esther. He writes that “hapax legomena [terms that are only found once] in the Hebrew Bible, which are extant exclusively in the book of Esther and are quoted verbatim in Qumran texts, which were unquestionably authored by members of the יחד [Qumran community], evince the dependence of the latter on the former” (emphasis added throughout). These include:

- Specific vocalization of words in “conjunctive structure with the definite article,” a “distinctive linguistic characteristic of the book of Esther.” For example, Esther 1:8—“אִישׁ־וָאִֽישׁ” and 8:9 “עַם וָעָם”—among numerous other conjunctive examples—the use of which Talmon believes influenced the Qumran community’s adoption of this linguistic element seen throughout other of their writings. (One extreme example of repetitive conjunctive structure is from 4Q416 1 6-7: “לממלכה וממלכה למדינה ומדינה לאיש ואיש”—“for all kingdoms and for all provinces and for all men.”)

- The use of the word “תר” in order of succession, in “waiting one’s turn,” is found only in such manner in Esther 2:12 and 15 and is used repeatedly in the same manner by the Qumran community.

- The pairing of the Hebrew words “light and happiness” (אורה ושמחה) occurs only in Esther; this pairing, while not absolutely certain, can be found on two Qumran texts.

- The expression of “my wish … and my request,” found nowhere else in the Bible, is present six times in the book of Esther. The same form is found in another apocryphal Qumran text.

- The stringing together of the words הפך ,שמח ,יגון ,אבל is found in Esther 9:22—and a similar line of text is found in 4QpHos. Talmon explained: “While in Esther the phrase is used in a positive sense, in 4QpHos it is given a negative turn. The literary transformation supports the supposition that the author deliberately quoted the expression in Esther with a pointed inversion of content.”

These examples are just a selection of Talmon’s evidence. He summarizes: “[The] employment of these phrases, which had no general currency in post-biblical (rabbinic) Hebrew, evinces the Yahad [Qumran community] author’s familiarity with them, buttressing the supposition that he knew the book of Esther.” Further, “[t]he linguistic-contentual parallels with Esther … [in the Qumran community] indeed support the claim that the authors of those texts were conversant with the tale of Esther and Mordecai.”

Textual Salvation

Considering this, is it accurate to say the book of Esther is not found among the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Qumran community? For now, the answer remains technically affirmative (for any of the manifold reasons described in the first part of this article). Yet that affirmation can also be misleading because, as the remarkable parallels from the late Qumran apocryphal texts show, there was a level of awareness and knowledge of this remarkable biblical work—and an apparently significant familiarity with it, at that.

As for the overall historicity of the book—despite widespread dismissal from skeptics—there is likewise a remarkable body of evidence for it, including the historical identity of Queen Esther herself. For more on this, read a thorough investigation by Gerard Gertoux here.

As such, in the spirit of the Purim celebration of a historic moment of Jewish salvation described in the book of Esther, it appears that the very scriptural text itself may be “rescued,” in its own right, from the clutches of desert destruction and obscurity at Qumran.