In a recent interview series hosted by the W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research, one of Israel’s most prominent archaeologists made some bold remarks about the Bible and its role in archaeology in Israel.

This man explained that David and Solomon were simple, hill-country chieftains, certainly not the towering monarchs recorded in the Bible. He theorized that the story of David and Goliath was invented during the time of King Josiah, and was crafted to reflect his upcoming clash with Egypt’s pharaoh Necho (Josiah was King David, Egypt was Goliath). He claimed that the account of Joshua’s conquest of Canaan was likewise invented during the seventh-century reign of Josiah. He also said King Solomon’s glorious reign was probably modeled by late biblical writers after an Assyrian king, maybe Sennacherib, and then perhaps blended with authentic aspects of the later kings Jeroboam ii and Manasseh.

This individual also shared some bold and controversial views about biblical Jerusalem. He claimed that Judah and Jerusalem only turned from a “godforsaken” place to an important kingdom in the late eighth century b.c.e., when they were incorporated into the Assyrian economy. And he claimed that Judah only became a truly literate state—allowing for the composition of the Bible—when educated Israelites from the north fled into Judah from their own Assyrian destruction during the same century.

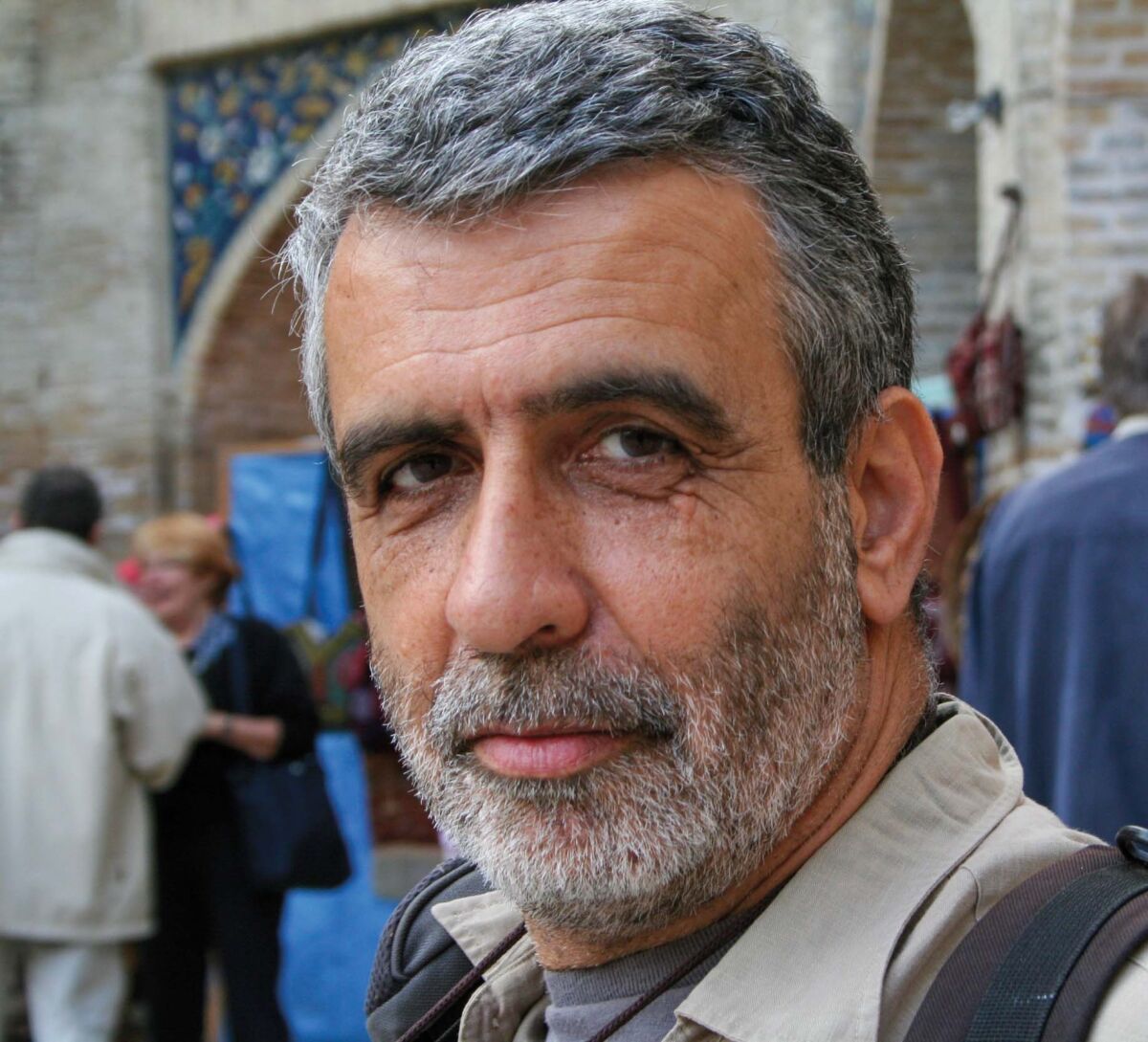

Many Jews, Christians, even Muslims would disagree with the views of Prof. Israel Finkelstein. It is easy to get upset by these claims. But the more important question is, what does the evidence say?

In the first interview of the series, Professor Finkelstein emphasized how important it is to “speak facts and data” when talking about ancient Israel and Jerusalem. And he is absolutely right! But here’s the context of that statement: “First and foremost, … the Bible does not mean to speak history. The Bible is all about theology, about ideology … and we scholars, researchers, need to speak facts and data” (emphasis added throughout).

Finkelstein clearly rejects the Bible as a historical source. But on what grounds? Where are the facts and data, the hard evidence—the science—proving that the Bible does not “speak history”?

Let’s examine Finkelstein’s claims specifically about biblical Jerusalem (Episode 15 of the series). Was Jerusalem a “godforsaken” place until the late eighth century b.c.e.? Is understanding Jerusalem of the united monarchy “a lost case,” as his interviewer concluded following Finkelstein’s comments? Is it correct for his interviewer to assert that “[e]xtensive archaeology has revealed nothing” about it?

This black-and-white view of Jerusalem is diametrically opposite to what the Bible records. What side does archaeology come down on?

Where Was Original Jerusalem?

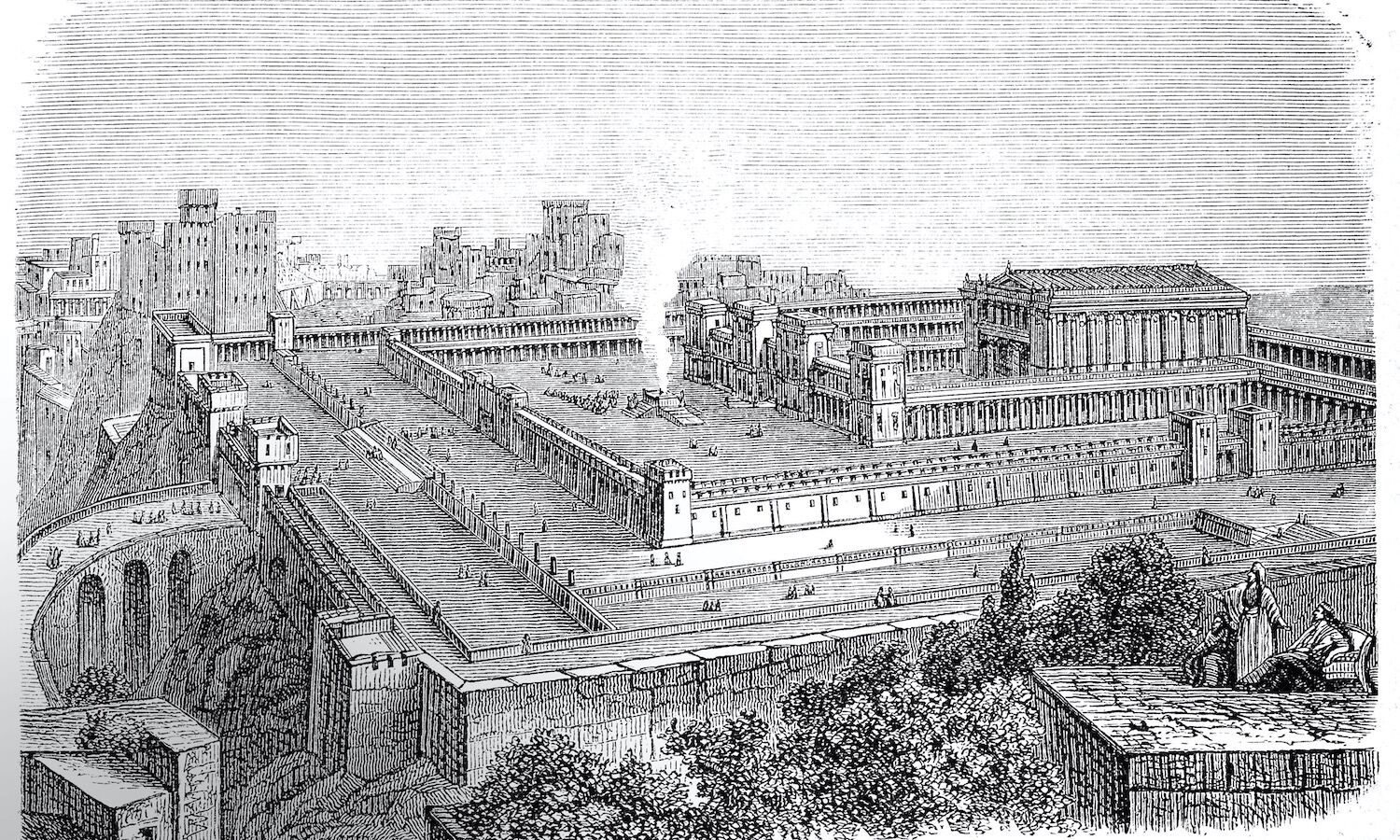

The interview begins with a discussion about the original location of Jerusalem. The majority opinion of scholars, archaeologists and historians is that early Jerusalem was situated in the area known today as the City of David, the ridge located south of the Temple Mount. According to the biblical text, David conquered this original city site ruled by the Canaanite Jebusites and made it his capital—and Solomon later expanded northward to include the temple.

According to Finkelstein, this understanding is flawed and there is “no way to clarify” where the ancient City of David really was. “We don’t really know what [these names] mean. We don’t really know what the Bible means when the Bible speaks about the City of David. There’s no place we can really pinpoint on the ridge to the south of the Temple Mount.”

Finkelstein believes the original city of Jerusalem was situated at the top of the Temple Mount hill, and that the city expanded southward down the ridge. He gave several reasons for this theory. First, he said, the City of David does not look like a typical “tel” mound as found at other cities around Israel. Second, he pointed out the lack of Bronze Age remains in the area, particularly the southern part of the City of David. And third, he explained that city mounds are usually situated at the top of the highest ground. “The City of David ridge,” he explained, “is completely dominated on three sides by higher grounds,” and this would have given enemies a tactical advantage.

Because of these reasons, Finkelstein believes that the original city of Jerusalem must have constituted a large tel mound located within the area today known as the Temple Mount. It’s an interesting theory. But how much of it is “facts and data”?

Consider his claim that we cannot know what the Bible means when it speaks about the City of David. The Bible is actually quite specific in describing the location of the original Canaanite city, Jebus. First, it says explicitly that the original Jebusite fortress in Jerusalem, captured by David, was renamed the City of David. 2 Samuel 5:7 tells us “the same is the city of David.” Furthermore, this passage states that this fortress (metzudah in Hebrew) was located in a lower ridge location—“down” from the highest geographical features (verse 17).

The Bible also indicates that the site was atypically small and extremely well-defensed geographically. In verses 6 and 8, the Canaanites boast that the city’s defense is so strong, even “the blind and the lame” could defend it. Finally, the Bible also reveals that the upper site of the future temple was part of an agricultural area outside and above the original city (1 Chronicles 21:18-19; 22:1).

Professor Finkelstein suggests that a settlement on the lower ridge would have been a strategic liability, but this view is not borne out historically. Jerusalem has been conquered numerous times. While the northern Temple Mount area is technically the highest point, this area is also a more-gradually sloped, broader area. Historically, this is the point where the city has typically been breached. When the Romans invaded in 70 c.e., they attacked the city from north of the Temple Mount. The Babylonians attacked the same point when they conquered Jerusalem in 586 b.c.e. This was the point where Assyria’s King Sennacherib threatened Judah with his armies in the late eighth century b.c.e. (although an attack did not take place). This was also the location where part of the city wall was torn down by the attacking kingdom of Israel (2 Kings 14:13).

The ridge and small summit on which the City of David sits is actually an extremely difficult area to penetrate. The bedrock on the east and west sides of the ridge falls away sharply, creating narrow valleys that become a kill-zone for large forces.

The fact that the City of David doesn’t fit the mold of a large “tel” mound, and that it has a comparatively lower elevation, may not accord with Mr. Finkelstein’s conceptualization of early Jerusalem—but it does fit with the historical accounts.

Now what about the purported lack of Bronze Age remains?

Where Is Bronze Age Jerusalem?

Archaeology in Israel and the ancient Near East is divided into several periods. The Bronze Age spans the third and second millenniums b.c.e. (put simply, Early Bronze, circa 3000–2000; Middle Bronze, circa 2000–1500; Late Bronze, 1500–1200 b.c.e.). Where are the remains of Jerusalem from the middle of the second millennium b.c.e.?

It is clear from Egyptian inscriptions, as Finkelstein highlighted, that Jerusalem was occupied in the Bronze Age—both the Middle and Late. Where, then, are these remains on the City of David ridge? After all, as Finkelstein notes, in areas of the southern ridge there is bedrock under Iron Age remains, and we have “only a [Bronze Age] sherd here or a sherd there … we don’t have at all evidence, or almost none, for architecture, houses, any construction activity.” Due to the lack of Bronze Age remains in the City of David, Finkelstein concludes that Bronze Age Jerusalem “must have been located on the Temple Mount” (although, as he admits, this theory cannot be put to the test by excavation due to the religious and political situation).

Before getting into what has been found, consider what has not been found.

While the City of David isn’t as politically or religiously sensitive as the Temple Mount, it is still incredibly sensitive. Much of the area is situated in the densely populated Arab neighborhood of Silwan. This makes it difficult to conduct large-scale excavations that would expose large swathes of territory. Instead, archaeologists have to excavate smaller areas, building their picture slowly over time, in fits and spurts.

Next, recall that Jerusalem has been destroyed and rebuilt several times over the centuries. The Bible describes the Judahites destroying Jerusalem during the Canaanite Late Bronze Age period (Judges 1:8). It describes the Israelites tearing down Jerusalem’s walls c. 800 b.c.e. (2 Kings 14:13). It describes the Babylonians destroying the city, even tearing down walls, during their sixth-century conquest (2 Kings 25:10). The first-century historian Josephus recorded the Jews during the Hasmonean period cutting down the ridge hilltop itself in order to prevent it being used to build another “Acra” tower to dominate the city (Antiquities of the Jews, 13.6.7). Josephus also gave an eye-witness account of the Romans of his day uprooting even the foundations of Jerusalem’s walls (Wars of the Jews, 7.1.1).

Ancient Jerusalem has been bulldozed multiple times over. According to Eric Cline’s book Jerusalem Besieged, the city has been “besieged 23 times, attacked an additional 52 times, and captured and recaptured 44 times.” This, too, explains the lack of Bronze Age evidence—much of it was destroyed in these attacks.

Finally, despite the relatively small area that has been excavated, and all of the destructions that have occurred, there is dramatic archaeological evidence for Bronze Age occupation in the City of David.

Archaeological excavations around the Gihon Spring—situated in the lower, northeastern corner of the City of David—have revealed part of a truly massive fortification, one that dates to the Middle Bronze period (circa 2000–1500 b.c.e.). This fortification wrapped around and protected the vital Gihon Spring. Its walls are massive, up to 7 meters wide at their foundations—the widest walls of any Bronze Age site in all Israel.

The Gihon Spring is Jerusalem’s only water source, something imperative to the survival of the population in a parched climate. And the spring is located on the lower ridge of the City of David, partway down into the eastern Kidron Valley. The location of this spring, and the tunnels that link it to the City of David (not the Temple Mount), are some of the greatest proofs of the location of the original site of Jerusalem—built deliberately around and protecting the vital spring.

Prof. Finkelstein recognizes this massive Middle Bronze age fortification in the lower City of David. However, to reconcile it with his theory, he suggests that this giant structure was simply a stand-alone building, an outlying tower from the Temple Mount city-hub, built to protect the distant spring. (He also postulates that the underground network of ancient tunnels beneath the City of David, leading to the Gihon Spring, simply gave late writers the idea to craft a story about David conquering Jerusalem using them.)

Consider the facts—what is the most rational explanation? Why do these Bronze Age tunnels connected to the Gihon Spring lead into the City of David, and not north, into the Temple Mount? This suggests the City of David was the central habitation at this time, not the Temple Mount.

Consider too: Is it difficult to believe that Middle Bronze Age structures such as these continued to be used in the Late Bronze Age period? And what about other Canaanite-era walls discovered on the lower eastern slopes of the City of David, better sheltered from exposure and destruction?

It is worth noting that the man who interviewed Professor Finkelstein questioned his theory of a Bronze Age Jerusalem centered on the Temple Mount. The interviewer identified certain difficulties with the theory, such as the exposed bedrock at the center of the Temple Mount site. In response, Finkelstein noted that erosion down to bedrock at an elevated point of the site is not unusual (again, structures are usually better-preserved in lower, more sheltered areas of a site). He also pointed out that we shouldn’t expect to find much on the Temple Mount anyway, given Herod’s clearing and rebuilding of the site for his temple.

How ironic. These are the same explanations for a lack of Bronze Age remains in much of the City of David—the exposed, eroded bedrock along the upper, southern part of the ridge, as well as repeat events of destruction and rebuilding. Here’s the key difference though: The only remnants we have of Bronze Age Jerusalem are in the City of David, not on the Temple Mount. Because something can be said to the question of Bronze Age remains on the Temple Mount: Sifting and various analyses have been done on the many tons of earth illegally bulldozed out of the Temple Mount foundations by the Islamic Waqf, along with other underground surveys of the Temple Mount (including various areas that extend down to bedrock). As affirmed by Dr. Hillel Geva and Dr. Alon De Groot, there is no evidence of tel stratification, and only 1 percent of the material remains discovered date prior to the Iron Age (most belonging to the eighth century b.c.e. onwards)—rather damning evidence against this site as the location of a strong Bronze Age city tel.

The United Monarchy

Finkelstein’s strongest broadsides were aimed at David and Solomon. As his interviewer concluded, “Jerusalem seems to be a lost case. Extensive archaeology has revealed nothing” about the united monarchy. In the interviews, Finkelstein discusses two main archaeological features related to this period: the Stepped Stone Structure and the Large Stone Structure (better known informally as “King David’s Palace”).

Both structures were excavated from 2005 to 2008 by the late Dr. Eilat Mazar, who famously identified the monumental remains as a singular, palatial structure dating to the 10th century b.c.e. (fitting with the biblical account of David’s palace-building in 2 Samuel 5).

The Stepped Stone Structure served as a massive supporting revetment against the precarious and narrow northern slope of the City of David ridge, allowing support for a large public building above and the continuation of a city wall. Dr. Mazar showed that the Large Stone Structure (David’s palace) was the building for which the Stepped Stone Structure was built (excavation revealed that the two actually interlocked, indicating they were part of the same supreme structure).

Professor Finkelstein, of course, disagrees. He claims the Stepped Stone Structure was built at a time “when the city starts expanding south from the Temple Mount,” and “in my opinion, we are dealing with support of the slope in different periods.” But what about the pottery retrieved from between the courses of stones proving the building was built in the late 11th or early 10th centuries? Finkelstein says this pottery dates to the ninth century b.c.e., not the 10th century. “This structure should be dated to the ninth century, or to the even beginning of the eighth century b.c.e.,” he claims.

Indeed, there is some debate among scholars as to the dating of the Stepped Stone Structure. However, Finkelstein’s proposition that it dates as late as the eighth century is rejected by most Jerusalem archaeologists.

As for the Large Stone Structure, or King David’s palace, Finkelstein explains: “I don’t think that we are dealing there with a single building. There are several walls, remains there; they do not all come from the same moment, from the same period. And I think that the earliest construction there should be put also in the ninth century b.c.e. Perhaps together with the revetment on the slope, perhaps they were connected … but we are not dealing with monuments from the 10th century. So there is no escape, in my opinion, from stating, from saying, from asserting, that the city of the time of David and Solomon was located on the Temple Mount.”

It is worth noting that in the first interview of the series, Finkelstein admits that he is not a pottery specialist. “Sometimes people ask me about my profession …. I don’t see myself, you know, as a specialist of the rim of the cooking pot or the storage jar, or the base, or whatever,” he says. Dr. Mazar, on the other hand, did specialize in pottery analysis, notably Iron Age pottery, and particularly that of the 10th century b.c.e.

But Dr. Mazar did not rely solely on pottery to prove the Large Stone Structure and the associated artifacts were dated to the 10th century. She also used carbon dating—a method of dating that is wholeheartedly endorsed by Finkelstein. (“Radiocarbon is not influenced by the Bible,” he stated in Episode Nine). Dr. Mazar’s radiocarbon samples backed up her pottery dating—dating the building to sometime between the late 11th and early 10th centuries b.c.e.

And what about his theory that the walls of the Large Stone Structure do not relate to a single building? This is peculiar, given that there are very few walls making up the palatial structure. There are only two primary, gigantic walls forming a right angle that make up the main northern outline of this building. Are these two massive walls—exposed up to 30 meters long, and 6 meters wide, forming a palatial enclosure—meant to be from separate buildings?

There is also the obvious question: If the massive Large Stone Structure isn’t a palace, then what is it? “In my opinion … I understand this structure as some sort of a fort protecting the water that was built in the ninth century when the city expanded,” Finkelstein stated. But what about the Spring Tower? If the Spring Tower alone was sufficient to guard the Gihon Spring far outside of Finkelstein’s original Jerusalem walls, why would an expanded Jerusalem border southward around the spring require another enormous secondary tower to defend it?

Consider too: What about the many 10th-century remains discovered by Dr. Mazar on the Ophel, which Mazar identified with the biblical account of King Solomon’s northward expansion of the city toward the Temple Mount? What about the 70-meter-long, up to 6-meter-tall “Straight Wall”? What about the Solomonic gatehouse, dated to the 10th century, its measurements paralleling similar gatehouses around Israel to the nearest centimeter (indicating a singular, governing authority over the land at the time)? What about the directly associated Large Tower, which lies buried under the Ophel Road, with only its outline revealed (thanks to the tunneling efforts of Sir Charles Warren)—a tower which, if uncovered, would be the largest single Iron Age structure in all Israel? Are these 10th-century remains evidence of a so-called “godforsaken” city and civilization at this time?

With a casual remark or two, Mr. Finkelstein simply dates all these to the ninth century. He believes that “Jerusalem [of the united monarchy] seems to be a lost case—[that] extensive archaeology has revealed nothing.” The truth is, the science—actual pottery, some carbon dating and direct corroboration of the literary text to the 10th century—disproves Professor Finkelstein’s claims.

Persian-Period Jerusalem

One would think that the closer we get to the present, the easier it would be to find evidence of biblical events in Jerusalem. This isn’t the case for Finkelstein, certainly in regard to Persian-period Jerusalem. “In the Persian period, there is no indication of fortification. And this is against the idea of Nehemiah’s city wall,” Finkelstein claims. “In Jerusalem, there is not even a single place where you can point to a piece of fortification from the Persian period.”

This is a dramatic, unequivocal statement. Not a single piece of evidence of Persian-period fortification in Jerusalem—nothing remotely related to the story of Nehemiah’s wall?

What about Dr. Mazar’s highly publicized discovery in 2008 of a middle-Persian-period wall and tower in the City of David? Mazar was able to not only date this partial fortification line to the Persian period, but using both pottery and animal bone remains, she was able to date this wall to the middle of the Persian period (circa 450 b.c.e.). With this information, Mazar identified the wall as the one built by Nehemiah (in 444 b.c.e., according to biblical chronology). Once again, Dr. Mazar documented and published her science.

Professor Finkelstein can disagree with Mazar’s identification of the wall as Nehemiah’s. But it is egregiously wrong to say, without qualification, that “there is not even a single place where you can point to a piece of fortification from the Persian period.” Where is the emphasis on “facts and data”?

It is also fact that several finds have been discovered relating to Jerusalem in the Persian period. In addition to Mazar’s wall and fortification, archaeologists have uncovered Persian-period pottery vessels and administrative material.

Archaeology and the Bible

One of the most central topics discussed in this interview series was the ongoing debate about the Bible and archaeology, and the role of the Bible in archaeology in Israel. Mr. Finkelstein explains some of the history of this debate, tracing it all the way back to the 18th and 19th centuries and the emergence of the scientific rationalists in Germany.

He explains how that, ever since archaeology emerged as a field of study in the 19th century, there have been two camps, or schools of thought. “One camp, the camp of the more conservative approach, [the] more conservative scholars … basically walk[ed] in line of the biblical texts.” Advocates of this approach accept the Bible as a historical source and consider it a valuable resource in archaeology.

The other camp is critical of the Bible and the value it provides to archaeology. Adherents of this view are often referred to as biblical minimalists. The roots of this view, as Finkelstein explains, extend all the way back into the 17th and 18th centuries, the age of German rationalism, when scientists became critical of the Bible.

For almost two centuries now, the pendulum has swung between these two camps. Since the 1980s, the advantage lay with the biblical minimalists, figures like Israel Finkelstein. Today, however, Finkelstein hints that the pendulum is moving in the other direction. “In my opinion, now we are in a new phase of attempts to show that archaeology can strike back at the critical approach ….”

Setting aside his view that these are mere “attempts,” his remark does recognize a certain scientific reality. Over the past two or three decades, archaeological excavations across Israel have furnished a bounty of evidence—including pottery inscriptions, bullae, ancient walls and complexes, and other tangible artifacts—that clearly support the biblical text.

Check it out for yourself. Take a look at the work of Dr. Scott Stripling in Shiloh, or the work of Tel Aviv University’s Dr. Erez Ben-Yosef at Timnah, or Prof. Yosef Garfinkel in Khirbet Qeiyafa. Our website has shined the spotlight on the lifelong efforts of Dr. Eilat Mazar in the City of David and the Ophel in Jerusalem. All four of these respected archaeologists, and many others too, have uncovered archaeological evidence across Israel that establishes the credibility of the Bible as a book of history.

To his credit, Finkelstein appears to accept that archaeology, in his words, is striking back at the biblical minimalists. Dr. Mazar always said that we must “let the stones speak”—and they are!

The stones tell us that ancient Jerusalem, just as the Bible reveals, was indeed situated on the City of David ridge, right beside the Gihon Spring. The stones tell us that Jerusalem during the 10th-century united monarchy, just as the Bible relates, also was a large and impressive civilization. The stones tell us, just as the Bible reveals, that Jerusalem in the 10th century was anything but “godforsaken.”

Finally, and most importantly, the stones tell us that the Bible is both a credible and indispensable resource in archaeology in Israel.