Prof. Yosef Garfinkel is the Head of the Institute of Archaeology at Hebrew University. He has directed excavations in the Judean lowlands at the sites of Khirbet Qeiyafa, Tel Lachish and, most recently, Khirbet al-Ra’i. In August, Professor Garfinkel sat down with amiba correspondent Brent Nagtegaal to discuss his excavation at Khirbet Qeiyafa and its impact on the ongoing debate over the united monarchy.

Brent Nagtegaal (BN): I recently finished reading your 2016 book, Debating Khirbet Qeiyafa, A Fortified City in Judah From the Time of King David. This book addresses two important topics. First, it explains what you found at the Khirbet Qeiyafa excavation. But it also provides a compelling look at the current state of biblical archaeology in Israel. I’d like to discuss both these topics today.

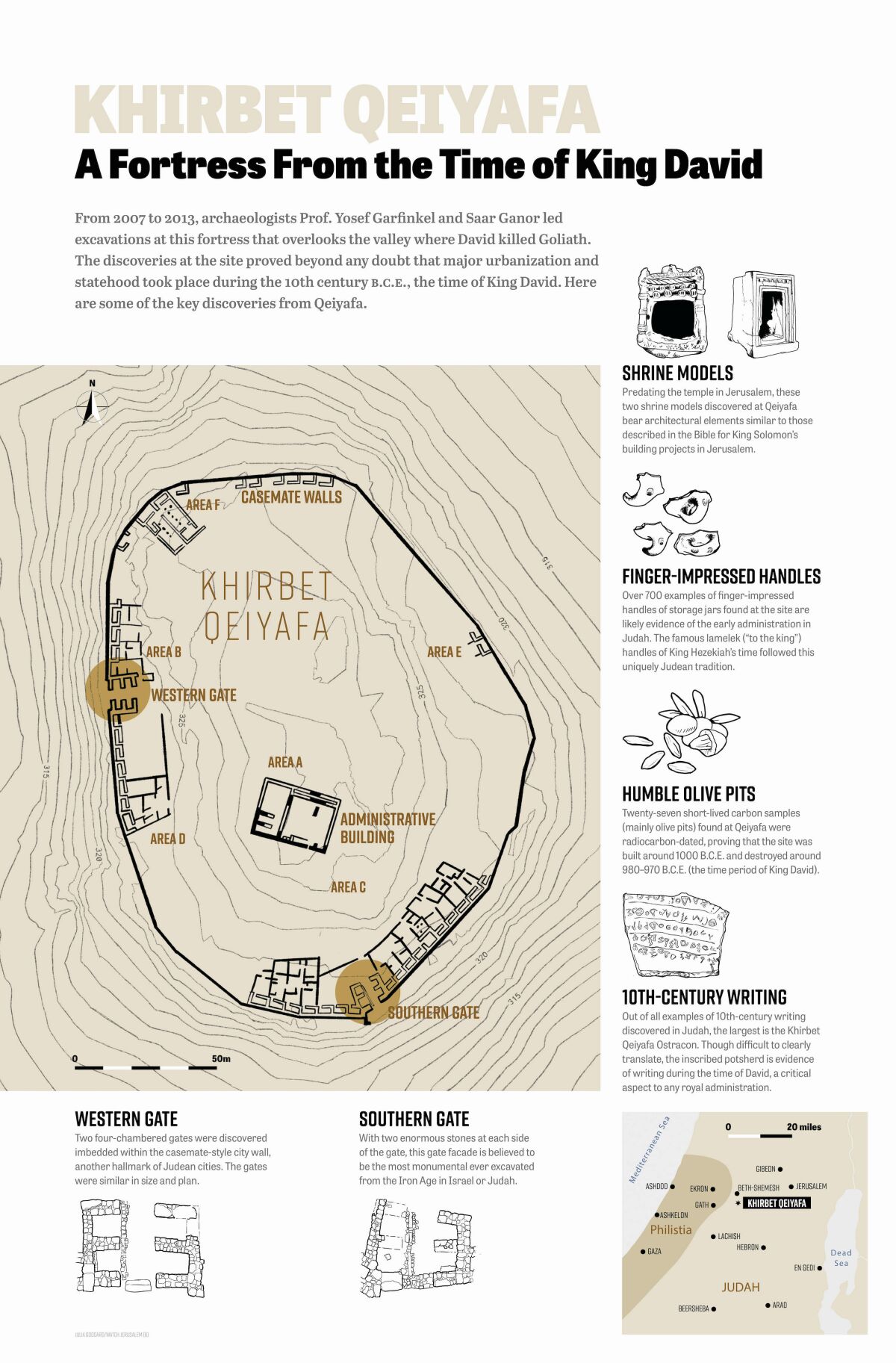

First, could you summarize Khirbet Qeiyafa for us—where it is, when it was excavated, the time period you are uncovering, and what you and your team have found?

Yosef Garfinkel (YG): Khirbet Qeiyafa is a small site. [It’s] not even a tel, like Tel Lachish or Tel Hazor. “Khirbeh” means small site. When you visit Khirbet Qeiyafa, you can see the bedrock on a large part of the site. [This] means the occupation [layer] is not thick, but rather shallow.

When I came to Khirbet Qeiyafa, I was amazed by the location. The site overlooks the valley of Elah, the main route leading from the coastal plain into the hill country. It’s also on the border between Judah and Philistia, and it was very clear to me that the location is very important.

BN: When did you start excavations?

YG: In 2005, I visited the site with Sa’ar Ganor, my student. We then excavated the site together for seven years, from 2007 to 2013.

BN: Tell us about the main occupation layer, and some of your discoveries.

YG: When we started excavating, typically we found remains from the Hellenistic [Greek] period. We discovered a lot of coins, including a silver coin of Alexander the Great; this was very nice. But then, when you go down [below the Hellenistic layer], there is a thick layer from the early 10th century b.c.e.—the time of King David.

BN: Is this why you excavated Khirbet Qeiyafa—to find evidence of King David?

YG: Not at all. When we [first] came to the site, we didn’t find much pottery on the surface. I was attracted to the site for two reasons. The first is the location; and second, there is a very heavily fortified city wall encircling the whole site, with bedrock exposed. Together, these were both indications that the site was not occupied for a long period. I didn’t know what would be the period of occupation during the Iron Age.

BN: What were you expecting to find exactly?

YG: I didn’t expect anything. I [believed] it would be a beautiful city, close to the surface, and [that it would] be possible in a short time to excavate a large part of the city. But I had no idea whether the city would be from the 10th century, ninth century or eighth century b.c.e.

In the first season, we only excavated for about 10 days, and with only a small number of people. But after [only] 10 days, it was very clear that we discovered a gate, city wall and houses. Underneath the Hellenistic level, we had the Iron Age [material]. On the floors, which were on bedrock, we discovered a rich assemblage of a destruction level. This was fascinating—we had found an Iron Age city that was suddenly destroyed.

The dating of the pottery from this first season … was not clear. I showed it to experts like Prof. Amihai Mazar and Alon de Groot. They looked at it and said that it looked earlier than the Sennacherib campaign around 701 b.c.e. So, earlier could be early eighth century, maybe late ninth. Nobody was dreaming about the 10th century.

In the second season, we excavated a larger area and found nice assemblages of pottery. I looked at the pottery and it was similar to the pottery found in Level vii at Beersheva and Level iv at Tel Batash. These levels at these sites are from early Iron iia, which is the early 10th century b.c.e. Yet these two sites were unfortified villages. But we found this same pottery in Khirbet Qeiyafa, which was clearly a fortified city. This was very exciting—I had this feeling in my fingers that I was going to have important discoveries.

The big breakthrough came only after we sent olive pits for radiocarbon dating. The radiocarbon dating gave us the date of 1000 b.c.e. This was a shocking moment: [We had discovered] a fortified city in Judah from the time of King David!

BN: Why was this so special and important?

YG: There is a whole debate about whether King David was a historical figure or a mythological figure. And if he was an actual historical figure, was he just a Bedouin Sheikh living in a tent, or did he have a well-established kingdom? A kingdom is not abstract. [A kingdom] has fortified cities on its borders, it has trade routes and writing. You have the collection taxes, and an administration. This is the big question: Did such an administration exist in the early 10th century b.c.e.?

[At Khirbet Qeiyafa], we have a fortified city on the border of Judah, opposite the Philistine city of Gath. We discovered hundreds of jars with a finger impression, which is typical to Judah. We discovered public buildings; we discovered two inscriptions. Khirbet Qeiyafa completely changed the picture [of King David].

BN: Can you explain what you call the “David in a tent” paradigm? The scientific term is “low chronology.” What does this mean?

YG: Up until the beginning of the 1980s, people accepted the biblical tradition as preserving accurate historical memories. Then a big change happened. It started at the Copenhagen School and later Sheffield, and now this thinking is all over the world. [Many] people question how many historical memories are really imbedded in the Old Testament. Some people say zero. Until this time [early 1980s], people thought it was 100 percent. So a big debate began about how much [true] history is embedded in the biblical text.

Since then, the [biblical] minimalists went through an evolution. This can be broken down into three phases. [At first], they believed everything was mythological, that David never existed, that Solomon never existed, that there was never a temple in Jerusalem.

But in 1993, Prof. Avraham Biran excavated at Tel Dan and he found the Aramaic Stele, probably written by King Hazael. On the inscription, the Aramaic king said, “I killed 70 kings. I killed a king from Israel and a king from the house of David.” [The phrase] “the house of David” means a dynasty created by a David. This is about 100 to 120 years after David. After this was discovered, no one could claim that David was a mythological figure. [Here he was], mentioned in a historical source outside of the biblical tradition. So this mythological paradigm of King David collapsed.

Three years later, the low-chronology paradigm emerged. This view accepts that there was somebody called David, but [suggests that] he did not have a kingdom as the Bible describes.

Here we have a sociological process. First, there is a tribal community at the time of Judges. This is what archaeologists call Iron i. Then you have the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. This is the time of the monarchy where you have fortified cities, administrations and kingdoms. The big question is, when did this sociological process take place? If it took place at 1000 b.c.e. as the biblical tradition says, then this is the time of David.

But low chronology says that it didn’t happen during David’s time, but rather it happened 100 to 200 years later, first in the kingdom of Israel, and about 300 years later in Judah.

BN: So essentially, low chronology puts King David into the Judges scenario where there are unwalled villages rather than the material culture associated with monumental structures. But your excavation at Khirbet Qeiyafa proves that is not the case?

YG: Exactly. There is a big debate about when urbanism started in Israel and Judah. At the start, nobody was talking about the 10th century. People were saying it began in the ninth century, or eighth century, or late-eighth century in Judah. At first, thousands of scholars already believed in low chronology. There was even a project in Hebrew University’s Institute of Archaeology by one of the archaeologists where they checked about 400 examples of radiocarbon dating. Most of them gave the date for the move toward urbanism in the ninth century b.c.e. These archaeologists even wrote an article saying that radiocarbon supports low chronology.

This is when I entered the picture. Before I excavated Qeiyafa, I excavated prehistoric sites from the Neolithic period, the beginning of agriculture. I was never involved in this debate surrounding David.

Then in 2007 we came to Khirbet Qeiyafa. In 2008, we discovered a city with houses, a casemate city wall, a gate and an inscription—the [famous] Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon. And then we sent olive pits for radiocarbon dating. And the big surprise that nobody expected—it was really shocking in a way—was that site dated to 1000 b.c.e., the time of King David.

This means that we have a fortified city in Judah from the time of David. So you cannot argue anymore that urbanism started in this region in the ninth or eighth century, because Khirbet Qeiyafa really shows that it started in the early 10th century b.c.e.

Only 10 days later, an article was printed in an Internet journal that claimed that Khirbet Qeiyafa was a Philistine site and didn’t belong to King David.

BN: This takes us to your 2017 paper, “The Ethnic Identification of Khirbet Qeiyafa: Why It Matters?” You wrote: “These scholars have already held, for 10 to 20 years, the position that the kingdom of Judah was established only in the late ninth or eighth centuries b.c.e. In other words, Khirbet Qeiyafa’s new data challenged their earlier conclusions. In this case, they have two options in front of them: either to alter their older approaches, or to hold on to them and suggest a new interpretation for the ethnic identification of Khirbet Qeiyafa’s population.” Can you elaborate on this?

YG: It is a kind of patchwork. If you look at the minimalist, the earliest minimalist has a very good methodology. They said: “OK, the Bible is not history, it is all mythological, so we cannot write the history of ancient Israel.” This is a complete approach. A person can either agree or disagree with it, but it is logical.

But when the Tel Dan stele was discovered which mentions David, this paradigm collapsed. The low chronology paradigm was developed to explain the Tel Stele. But then came Khirbet Qeiyafa, which proves that the low chronology dating is not correct. So they had to introduce another patch, this time about the ethnic identification.

First, they claimed that Qeiyafa was a Philistine site. Then some said it was a Canaanite site. Others said it was Israelite and was built by King Saul. And others said it was Judean. So you have four different suggestions about who lived in Khirbet Qeiyafa. The question is: How do you decide? What is the methodology?

The methodology is comparative analysis. We took various aspects that were found at the site of Khirbet Qeiyafa and we compared it with Canaanite sites. We compared it with sites in Philistia. We compared it with sites in the northern kingdom of Israel. And we compared it to sites in Judah.

First, we looked at urban planning. At Khirbet Qeiyafa there is a casemate city wall and houses abutting the casemate. There are five examples [we can compare]: Tel Nasbeh, near Ramallah; Beth Shemesh; Beersheva; Tel Bet Mirsim; and Khirbet Qeiyafa. All of them are in Judah. There is not one Philistine, Canaanite, or Israelite site that has this urban planning.

Then, we took the animal bones. We have 100,000 animal bones at Qeiyafa, and not one of them is a pig bone. At Canaanite sites, 4 to 5 percent of the animal bones are from pigs. At Philistine sites, up to 20 percent of the animal bones are pigs. So our site is not Canaanite nor Philistine, according to the animal bones.

BN: Just to recap: The first paradigm collapsed when the Tel Dan Stele was found; the second paradigm—low chronology—collapsed when you found urban planning from 3,000 years ago, from the time of King David. So at this point, the critics said, “OK, you’re right, you did find urbanization, but it’s not King David—this site doesn’t belong to Judah.” But this is wrong too, because these different parameters match Judah more than any other ethnic group or material culture of any other ethnicity.

YG: Yes, and the same scholar that said it was Philistine also said four years later that it was Canaanite. [But] these scholars that said it was Philistine or Canaanite or Israelite didn’t give arguments. They didn’t say it is Philistine because of reason A, B or C. They didn’t say it belonged to the kingdom of Israel because of reason A, B or C. They just wrote it because they wanted it to be Israelite, or Canaanite, or Philistine.

BN: In your 2017 article, you wrote: “Placing the current debate in its accurate place within the history of research clearly indicates that the subject was dealt with in a polemical way, rather than using a balanced, scientific view.” What does this mean?

YG: It means the idea of biblical minimalism has become a religion. If something is written in the Bible, [the truth] must be opposite. You can see this in article after article. They are debating the biblical tradition, whether their arguments fit or don’t fit the data. People should be aware that sometimes the archaeology and the biblical tradition don’t match 100 percent, because every historical narrative sometimes has its own view, etc. However, the minimalists are trying to destroy 100 percent of the biblical tradition. This methodologically is incorrect. If you said white, [these people would say] black. But if you said black, they would say white.

The question is, how do you build scientific theories? The way I understand it, you take [facts] A and B and C and D, and then you build a theory. But what the minimalist school is doing is saying that we can [ignore facts] A, B and C, and just build a theory. But once you find A or B or C, their theories immediately collapse. You cannot build your theories on the lack of data. You should build your theories on what you have—not on what you don’t have.

BN: Can you give an example?

YG: [Take the Hebrew University] radiocarbon project which took 400 samples and found that most came from the ninth century b.c.e. How come Khirbet Qeiyafa changed the picture? [It was] because these 400 samples were taken from the kingdom of Israel. The samples were taken from Dor, Hazor, Megiddo, Bethshan, Rehov and other sites. They [considered samples from] sites in the kingdom of Israel, which even in the biblical text the kingdom of Israel is established in the late 10th century. So most of the sites that were built and fortified were in the ninth century, so of course you get ninth century from sites in Israel.

But they took it to [try to] prove that the Bible is wrong. They didn’t look at the geography and consider regionality. Judah started in the 10th century and Israel in the ninth century. … You need to date every region by its own area. You cannot predict from one area to the other.

BN: Here’s one of my favorite quotes from your book. “Since so much detailed research in biblical archaeology has already been done on almost every aspect, it is hard to contribute a new paradigm. Some scholars have found a way to overcome this situation by constructing alternative hypotheses that are based on lack of data on the one hand, and rejection of existing data on the other. In this way, ‘original’ paradigms can be offered and the sky, or the authors audacity, is the limit. Such works would not have been published a generation ago, when scientific standards were more stringent. Today, however, in the postmodern intellectual atmosphere, there is much more room for original ideas, even if they are not well founded. Thus in our era there is no clear-cut boundary between science, science fiction and wishful thinking.”

Are you saying that the study of archaeology is actually becoming less scientific than what it was a generation ago?

YG: I think you take it too far. Scientifically, we are working better. We are collecting the animal bones. We are sending pottery for residue analysis. We are using radiocarbon dating. Our scientific method becomes stronger and stronger, and the involvement of archaeology and sciences (biology and botany, etc) is stronger and stronger all the time.

But what became crazy is not the archaeology, but the interpretations—[today] you can say whatever you want.

BN: So you believe we are seeing more archaeological theories based on ideas rather than evidence?

YG: One of the main problems in [archaeology] today is that I cannot write an article that agrees with [biblical archaeologist William] Albright, or that agrees with [biblical archaeologist] Yigal Yadin. But you can write an article that says, “I don’t agree with Albright,” or “I don’t agree with Yigal Yadin.” And this is what [is happening]. People are taking new data and old data and [they] are creating new hypotheses and are saying, “I don’t agree with this and I’m suggesting something new.”

The question is: What is the value of these new ideas? Do they have roots or [facts]? If not, it’s all hot air.

BN: We recently discussed the postmodern concept that there is no such thing as truth, and the impact of this on archaeology. Can you talk about that?

YG: Look at all the field of humanities, including literature and history and archaeology and biblical studies and other aspects of the humanities: If you don’t have a truth, then you can do whatever you want to do. But of course there is truth. The question is: How close can we get to the truth?

I think that by having more investigation and more accurate radiocarbon dating and excavating larger parts of a site, and having more inscriptions and more metal objects, we can know more and more about how people lived, and then we can have better understanding.

This is one of the things that I did. In Khirbet Qeiyafa, we excavated about one quarter of the city. In Lachish, we found a new city wall from the time of Rehoboam. According to biblical text, Rehoboam fortified Lachish. Yet without excavation, you cannot find the data. So I think that archaeology is the main source of new data for understanding the biblical tradition.

BN: Were you surprised by the accuracy of the biblical text from David’s time onwards, through Rehoboam? In Khirbet Qeiyafa, you waded right into the middle of the debate about David and Solomon. Were you surprised that Khirbet Qeiyafa proved the biblical narrative?

YG: It didn’t surprise me because I didn’t come with any biased thoughts, whether the Bible is 100 percent history or the Bible is all fiction. I see myself more as a scientist. Personally, I’m not a religious person, so the Bible is not holy for me. I know for billions of people in the world the Bible is a holy text. And I understand that. For me, it’s a historic text.

I’m not trying to prove the Bible or disprove the Bible. I want to know for myself what really happened. It’s really a scientific curiosity, a personal curiosity. I don’t care about low chronology/high chronology, maximalist/minimalist—I want to know the truth. This is my motivation. I, Yossi Garfinkel, I want to know what really happened. This is my motivation.

BN: From your scientific point of view, what is your summation so far of the 10th century b.c.e.?

YG: What I know is that we were working in Khirbet Qeiyafa and we found a beautiful city from the time of King David with two inscriptions indicating an administration. It was a wonderful discovery.

Then I went to Lachish, because I want to know more about the 10th century b.c.e. In Lachish, there is the biblical tradition about King Rehoboam fortifying the city. I wondered: If there is indeed fortification in Lachish from the time of Rehoboam, this would be late 10th century b.c.e. And indeed, in the excavation we found a new city wall which was not known before. Radiocarbon dating that we received from Oxford University shows us that the fortification is from the end of the 10th century, and the first half of the ninth century b.c.e. So this city was really built by King Rehoboam.

And then we have the shrine models found at Qeiyafa; a nice model made from stone about 30 cm tall where you can see near the roof the beams organized together, and the door is decorated with recessed entrance. And if you read the biblical description of Solomon’s palace and Solomon’s temple, you can see the same architectural features appearing in the biblical text.

So in this way, I contributed to [our understanding of] David, Solomon and Rehoboam— the first three kings of Jerusalem. [And all three] cover the whole 10th century b.c.e. David in the beginning, Solomon in the middle and Rehoboam in the end, last part of the 10th century.

BN: Do you believe what you have done over the past 15 years has moved the needle back toward accepting the Bible as being more accurate from the 10th century? Are there others in the archaeology field that are coming back to that premise?

YG: I see that even scholars that have supported the low chronology and said that everything was built in the eighth century b.c.e. are moving it back to the ninth century b.c.e. So instead of a 300-year gap, there is now a 200-year gap. And I think that we still need to have a large-scale archaeological project in the kingdom of Judah to find more data about the 10th–9th centuries b.c.e. This is what I hope to do.

BN: Thank you very much for your time!

YG: Sure, it’s my pleasure.