The ancient region of Ophir—a place of wealth and gold—has captivated the imagination of men for centuries. You might recall the book by Henry Rider Haggard titled King Solomon’s Mines—or maybe the 1950 movie of a similar name, or perhaps the tv miniseries. The location has been a common quest for ancient explorers: A Portuguese explorer of the 15th century claimed it was in the Shona lands of Zimbabwe. Christopher Columbus thought he had found Ophir in Haiti; Sir Walter Raleigh thought it was in the jungles of Surinam. A Spanish captain in 1568 discovered an archipelago and, believing it to be Ophir, named them the Solomon Islands.

All this search with no concrete discovery can lead one to question: Is this place real?

An article published in 2017 by the Independent stated, “King Solomon’s gold mines, which the Bible says helped him store wealth amounting to more that £2.3 trillion, are a complete myth, historians believe.” The article quoted British historian and author Ralph Ellis, who said finding the lost mines was “about as likely as taking a dip in the Fountain of Youth,” concluding, “There comes a point when we either have to accept that the biblical account is entirely fictional, or that we may be looking in the wrong location and for the wrong things.” The author of that 2017 article wrote, “[E]xperts now say the pot of wealth is unlikely to have ever existed.”

Not so fast.

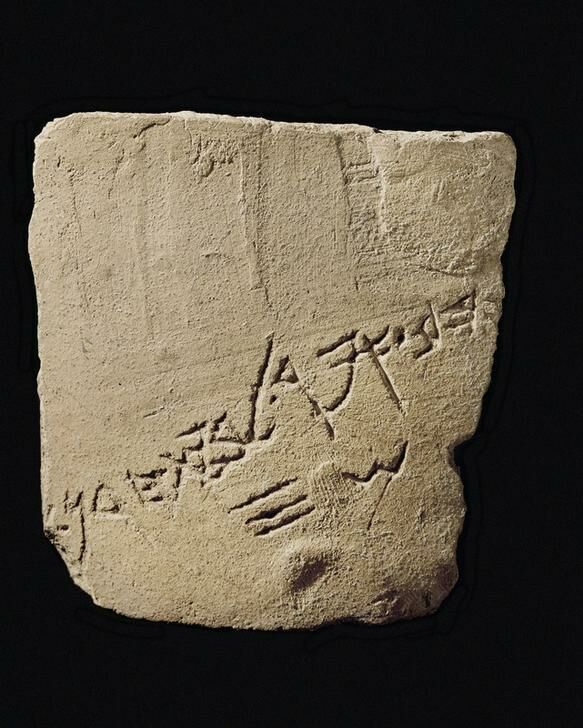

An ostracon (a pottery shard containing an inscription) found during the 1946 archaeological excavations of Tell Qasile (a site in Tel Aviv) validates the existence of that “pot of wealth”—Ophir. This ostracon, along with another discovered with it, served as an invoice and testifies to the importance of this settlement in the eighth century b.c.e. as a center for imports and exports. One of these ostraca, likely from an Israelite official in charge of the royal exports from Tell Qasile, describes 1,100 measures of oil for the king. The other reads as follows:

Ophir gold to Bet Horon – 30 shekels.

Renowned Israeli archaeologist Prof. Benjamin Mazar (who at the time went by his original surname “Maisler”) wrote in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies that “Bet Horon” is “apparently the twin-city, Upper and Lower Beth Horon, known as the city of the Levites (administrative center) in the district of Ephraim, a store-city in the period of Solomon, an important fortress on the road leading from the plain up to the mountains and situated on the border of Israel and Judea.” He postulated that the name referred to a temple of the Canaanite god Hauron.

Either way, this ostracon confirms the veracity of the Bible in its reference to Ophir in the ancient world. Professor Mazar wrote, “The Ophir gold … so called after the country of its origin, is apparently of an especially fine quality.” The Bible repeatedly describes the gold of Ophir as precious: Job 28:16 says that wisdom does not have a price, and “It cannot be valued with the gold of Ophir, With the precious onyx, or the sapphire.” Isaiah 13:12 says that in the Day of the Lord, a man will be “more rare than fine gold, Even man than the pure gold of Ophir.”

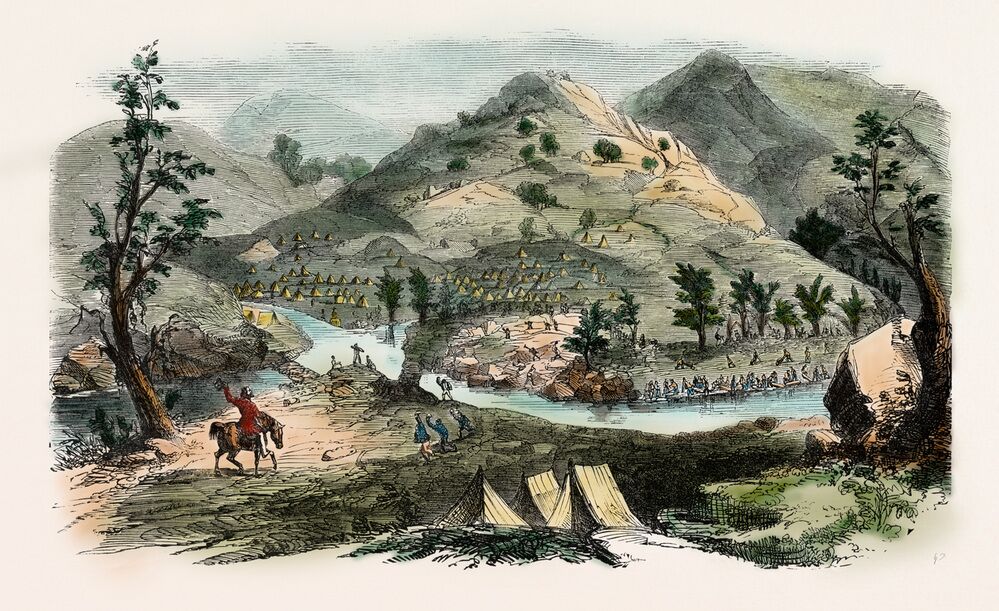

Solomon, with the help of the Phoenician king Hiram, built ships and sent servants who had knowledge of the sea to Ophir to bring back the greatly desired gold (1 Kings 9:26-28). Solomon had two navies: one based on the Mediterranean and one in Eilat. Sending servants who had “knowledge of the sea” shows that these ships were not taking short expeditions. They traveled extensively.

But where exactly did they travel? Theories abound. Some believe Ophir is in Sri Lanka or India; others think it is in Pakistan at the mouth of the Indus River or in Saudi Arabia; others believe it is in South America; and some theorize that Ophir was located in Australia—with India and other places as possible transit stops between the Red Sea and Australia.

2 Chronicles 9:21 tells us that the king’s ships were gone for three years at a time, and when they came back, they brought gold, silver, ivory, apes and peacocks. The port from which the king’s ships left to gather gold of Ophir is described in 1 Kings 9, referring to the one in the south—near Eilat, located in the Gulf of Aqaba, which connects to the Red Sea. Considering this port opened out to the Indian Ocean, it wouldn’t make sense for this fleet to go to South America for the gold, and Saudi Arabia would be too close for such a long trip. In addition, Saudi Arabia does not have many of these exotic items. It’s possible the fleet went to Australia or even east Africa, but it appears the gold of Ophir most likely came from the area of India, or perhaps Sri Lanka.

The Hebrew words translated as “ivory,” “apes” and “peacocks” in 2 Chronicles 9:21 are all of a foreign origin, relating commonly to India. Gensenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon says the word used for ape is “a word of Indian origin.” It’s likely that travelers from the land of Israel would have learned the foreign names for these exotic items, calling them by their foreign names when they returned to Israel. Considering India’s plenteous supply of all these commodities, it seems highly likely Ophir might be in or around India.

With all of this trade, Solomon’s accumulated wealth rose to almost unfathomable heights. His drinking cups were made of gold. He had 300 shields beaten from gold. His throne was made of ivory and overlaid with the best of gold. The steps leading up to the throne had 12 golden lions facing 12 golden eagles. Additionally, the temple in Jerusalem was adorned with 3,000 talents of gold (with a low-end valuation of $4.2 billion).

Other than the name, the Bible doesn’t give much detail about Ophir. And with so many unfruitful expeditions, it appears elusive. But the ostracon found near Tel Aviv does confirm its existence and the veracity of the Bible.