“Caged like a bird”—that’s how King Sennacherib described King Hezekiah during the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem in the eighth century b.c.e. The city was locked down and surrounded, with no one permitted to leave or enter. We know how the biblical story ends. Sennacherib’s army was dramatically and miraculously overthrown, and Jerusalem went on to enjoy a renaissance of rebuilding and prosperity.

Although it’s been a summer of lockdown for us too, that hasn’t stopped the flow of new archaeological discoveries. Over the past few months, two dramatic new finds from King Hezekiah’s “post-lockdown” Jerusalem were unveiled.

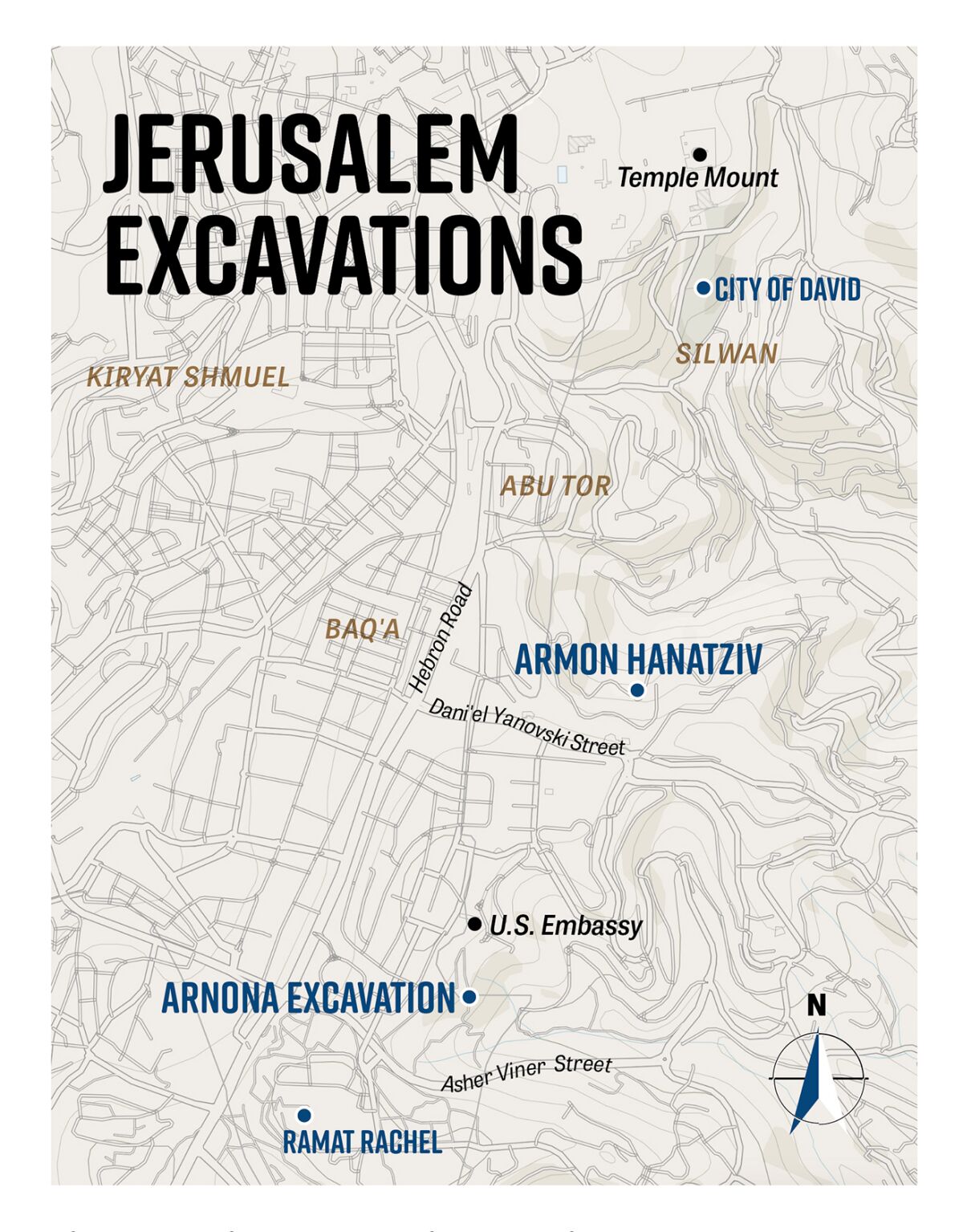

These entirely separate discoveries, uncovered by separate teams, share some striking similarities. Both are royal buildings. Both fit with the period of biblical resurgence and rebuilding following the Assyrian siege. Both were discovered within the area of outer, southern Jerusalem.

In the grim and frankly depressing world of coronavirus lockdown, archaeology has brought a ray of hope from King Hezekiah’s own “post-lockdown” renaissance.

Agriculture Administration Center

In late July, archaeologists working in the southern Jerusalem neighborhood of Arnona revealed a large, 2,700-year-old administration center established by King Hezekiah and used through the seventh century b.c.e. Inside the large storage center, they discovered one of the “largest and most important” seal collections in Israel: more than 120 administrative seals, alongside other discoveries.

The building itself was unusually large and impressive, constructed out of hefty ashlar stones. Peculiar was the fact that such an administrative facility would be needed so close to the capital, Jerusalem. This indicates that Hezekiah’s Judah was perhaps more powerful and prosperous than realized, and required a strong, closely interconnected network of administrative buildings. The building dominated what was then an agricultural area, made up of olive orchards, vineyards and wineries.

This building would have been used by the Judahite administration to collect and process tithes and taxes from the owners of the surrounding fields. This is shown, in part, by the seals discovered at the site.

Most of the seals were of the “lmlk” variety. This seal type began to be used during King Hezekiah’s reign, with the text commonly stamped onto the handles of storage vessels. There are five main types of lmlk seals, all of which bear the motifs of either a winged scarab beetle or winged sun. The Arnona seals mostly consist of the latter, a symbol that apparently took over toward the latter part of Hezekiah’s reign. The word lmlk means “to the king.” Many of the seals included the name of one of four Judahite cities: Hebron, Socoh, Ziph or Mmst (debate is open as to the meaning of this word).

Scientists agree that these seals, and the containers upon which they were stamped, served some kind of administrative, taxation or tithing purpose.

Besides the official lmlk seals, many pottery handles were also stamped with the personal seals of individuals. The names include “Naham [son of] Abdi,” “Naham [son of] Hazliah,” “Meshullam [son of] Elnathan,” “Zaphan [son of] Abmez,” “Shaniah [son of] Azariah,” “Shalem [son of] Acha,” and “Shebna [son of] Shachar.”

Evidently, these were prominent individuals, probably wealthy landowners or perhaps representatives of economic areas, who sent taxes or tithes to this administration facility. Several of these names have also been found on storage vessels at other sites, attesting to their prominent standing in Judah.

Most of these names parallel biblical names used during this late kingdom period. The names of two of the father figures, Abdi and Azariah, are mentioned together in 2 Chronicles 29:12 (a passage describing Hezekiah’s righteous reforms).

It is likely they represent the same administrative officials, but unfortunately there is insufficient genealogical information on the seals to be certain. Even if these individuals are not the same as those listed in the Bible, the use of these names helps verify the accuracy of the biblical account, given that names regularly fall in and out of use (as they do today).

Among the small finds at the site were a number of small pagan idols, including fertility figurines. The Bible notes Hezekiah for his generally righteous reign but identifies his son, Manasseh, as perhaps the most egregiously evil of all the Judahite kings, even leading the nation in child sacrifice. Perhaps these pagan items were used during the open hedonism of Manasseh’s reign.

It is interesting that most of these fertility idols discovered in Jerusalem—in the City of David, as well as at Arnona—have had their heads, legs, pedestals or breasts snapped off. 2 Kings 23:24 states that the righteous Josiah (who reigned at the end of the seventh century b.c.e.) destroyed “the idols” in Jerusalem. This would certainly have been done to large items. The condition of these gods and goddesses supplies evidence this was also done to the small.

Strangely, evidence shows that sometime during the seventh century b.c.e., the Arnona administration building was covered over by a massive pile of flint stones that rose some 20 meters high and spanned over seven dunams (two acres). The pile of partially excavated stones, within which the administration building was discovered, is still visible from a great distance. Archaeologists remain bewildered about its original use.

Stone piles such as this have been found at several other sites in Jerusalem—the Arnona pile is the largest. Were they related to the Assyrian or Babylonian invasions? Were they some kind of territorial marker? Or perhaps some sort of a memorial covering following the death of an important individual? Perhaps a demolition of a once-paganized site? Theories abound. One biblical passage may reference them. Jeremiah 31:21 reads, “Set thee up waymarks, make thee high heaps: set thine heart toward the highway, even the way which thou wentest: turn again, O virgin of Israel, turn again to these thy cities” (King James Version).

The Arnona site was destroyed at the start of the sixth century b.c.e. during the Babylonian invasion. It was resettled decades later, during the Jewish return, and continued to be used for another five centuries. Today, it is somewhat “famous” as the current site of the United States Embassy, having been relocated from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

The excavation of the Arnona administrative building was led by Nathan Ben-Ari and Neria Sapir of the Israel Antiquities Authority. “This is one of the most significant discoveries from the period of the kings in Jerusalem made in recent years,” they wrote in the July 22 press release.

Barely more than a month later, we learned of another one.

The Promenade ‘Palace’

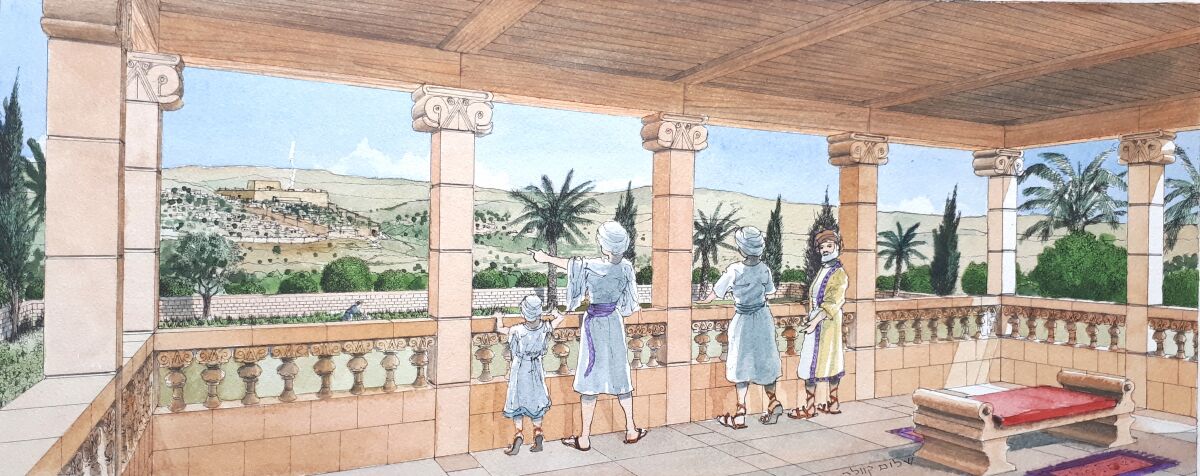

In early September, archaeologists excavating at Armon HaNatziv revealed the discovery of a trove of ornately carved architectural elements from a grand royal building dating to the seventh century b.c.e. The trove included several dozen stone pieces, including the best-preserved proto-Aeolic capitals ever discovered and items from “lavish” window frames, including balustrades of ornate columns.

Armon HaNatziv is a promenade area directly overlooking the City of David hill from the south. The modern name of the location is fitting. It means “Commissioner’s Palace” and was built by the British Mandatory administration 100 years ago. The British, it seems, had a similar idea to the early kings of Judah; they wanted an official building overlooking Jerusalem.

This structure dates to around 700 b.c.e., the time following Assyria’s siege during the days of King Hezekiah, and directly parallels the construction of another palatial structure at nearby Ramat Rachel (southwest Jerusalem). It also fits alongside the construction of the Arnona administration building. The excavators believe this royal promenade building was part of what they call an “exit from the walls” strategy instituted by King Hezekiah. When the threat of the Assyrian siege ended, Hezekiah began constructing royal administration buildings, storehouses and grand palatial buildings outside of Jerusalem’s fortress walls.

The most notable discoveries made at the Armon HaNatziv site are the proto-Aeolic capitals. A capital is the stylized uppermost part of a column. Capitals were highly decorative and made the pillar more stable. Proto-Aeolic capitals are famous architectural features from First Temple Period Israel; they feature two palm volutes. (The palm is a common motif in ancient Israel, featured most notably in the temple.) Dozens have been found around the country, dating from throughout the First Temple Period. Today they are depicted on the five shekel coin.

In the last issue, we published an article about the “finest proto-Aeolic capital” ever discovered from Kathleen Kenyon’s 1963 excavation in the City of David. Apparently we spoke too soon! The immaculate preservation of these newly discovered capitals far exceeds even that example. Of the three large capitals discovered at the site, two had been deliberately buried, one carefully placed atop the other, before the rest of the palatial building was destroyed during the sixth-century Babylonian conquest.

“This is one of the mysteries at this unique site, to which we will try to offer a solution,” noted excavation director Yaakov Billig. Perhaps the royal owner of the site—a nobleman, or maybe even the king of Judah himself—had wanted to ensure that the building’s finery was preserved for when the Jews would return, as had been prophesied (Jeremiah 29:10).

Together with the three large capitals, miniature “capitals” were also discovered at the site, serving as the caps of balustrade columns. This was the first time such a feature has been discovered (although they are known from ancient artistic depictions of window ledges). Together, the especially ornate capitals and balustrades adorned this palatial promenade.

At a September 3 event celebrating the discovery, Hili Tropper, the Israeli minister of culture, said the following words (which also sum up the discovery at Arnona):”I am happy and excited with the revelation of the remains from the period of the kings of Judah. The uncovering of the remains of the building reflects the glorious roots of the Jewish people and our rich past here in the capital city Jerusalem. I see great importance in the work of the Israel Antiquities Authority and in the work of the City of David in their discoveries over the years, which reveal parts of the illustrious Jewish past. This is an opportunity to thank the Ir David Foundation [Elad] that funded this important excavation. The past is the cornerstone of a nation, and the cornerstone of culture, and its discovery also affects the present as well as the future.”

A Biblical ‘Renaissance’

Taken together, the two Jerusalemite buildings at Arnona and Armon HaNatziv reveal a period of rebuilding, growth and prosperity following a time of deep depression, despair and destruction. It is a hopeful story, and one we all can benefit from right now. Most importantly, the archaeological picture fits precisely with the biblical account.

When Jerusalem was under threat from the Assyrians, and Hezekiah cried out to God in prayer, Isaiah prophesied the freedom of the nation. He foretold a miraculous agricultural resurgence, one in which no sowing would even be necessary for the first two years (Isaiah 37:30). Perhaps the reason the Arnona center was required so close to the City of David was to cope with these large harvests.

The Bible describes the ensuing magnificence and riches of Hezekiah’s reign. Its grandeur attracted even the faraway Babylonians, whose ambassadors he toured through the land (Isaiah 39, perhaps taking them up to the Armon HaNatziv promenade). This is how 2 Chronicles 32 summarizes Hezekiah’s reign following the failed Assyrian siege: “And Hezekiah had exceeding much riches and honour; and he provided him treasuries for silver, and for gold, and for precious stones, and for spices, and for shields, and for all manner of goodly vessels; store-houses also for the increase of corn, and wine, and oil [like Arnona]; and stalls for all manner of beasts, and flocks in folds. Moreover he provided him cities, and possessions of flocks and herds in abundance; for God had given him very much substance” (verses 27-29).

The biblical story—and now the discoveries—teach a powerful lesson and theme of the Bible: blessings for obedience, curses for disobedience. Disobedience to God brings persecution and suffering. It did throughout biblical times, and it does to this day. But when we listen to God and obey Him, when we turn to Him in repentance, He will deliver us from any trial—and bless us with more than our “Arnona” storehouses can handle.