A new, first-of-its-kind study has revealed evidence that ancient Judah was a much more literate society than scientists assumed.

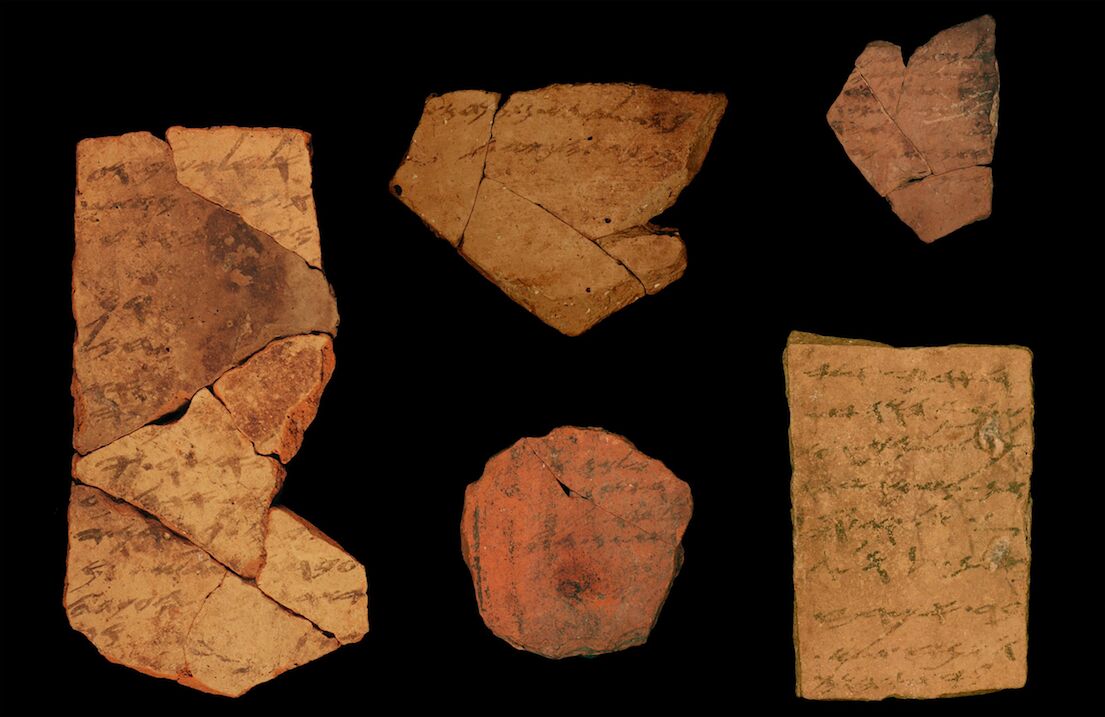

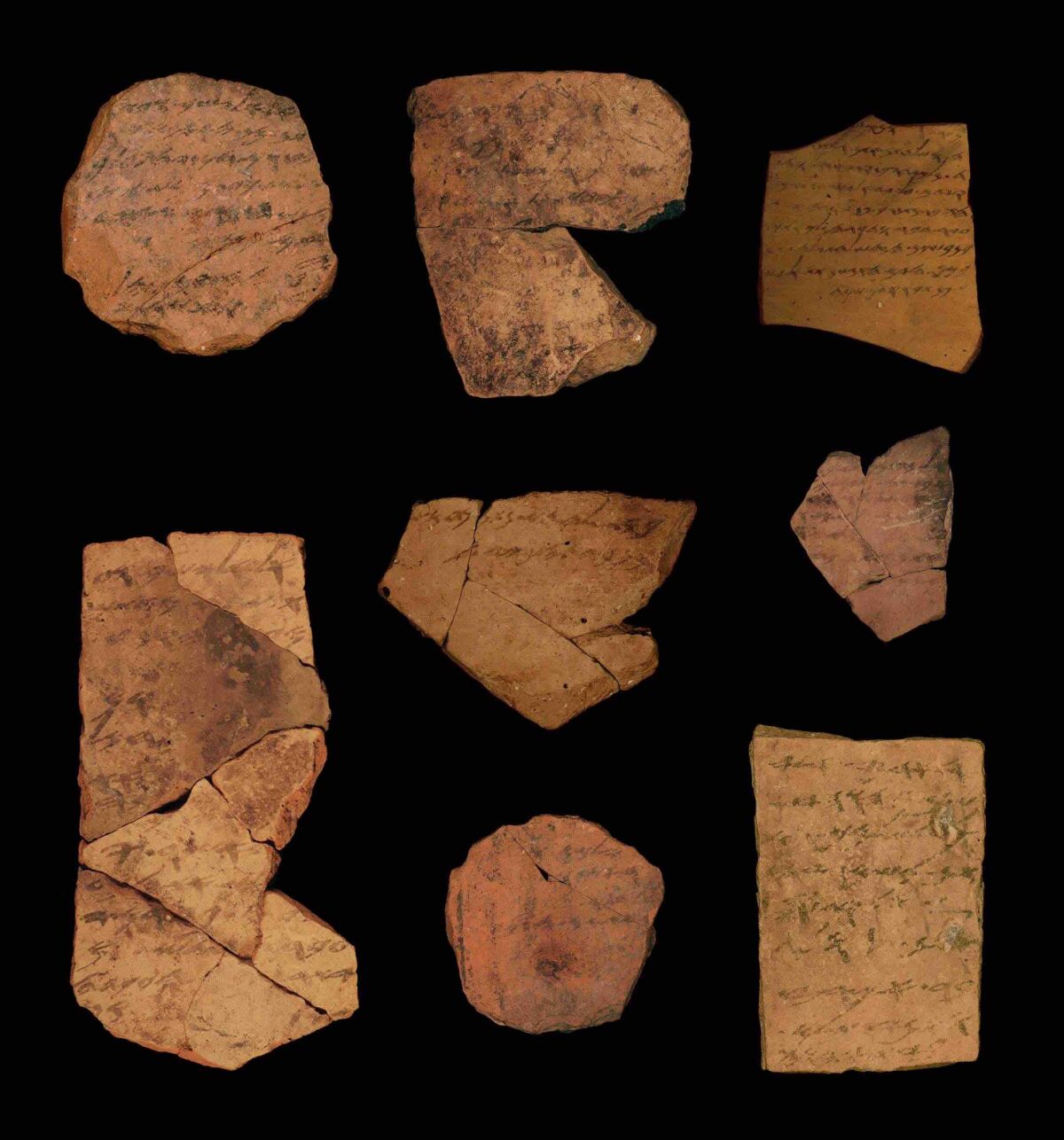

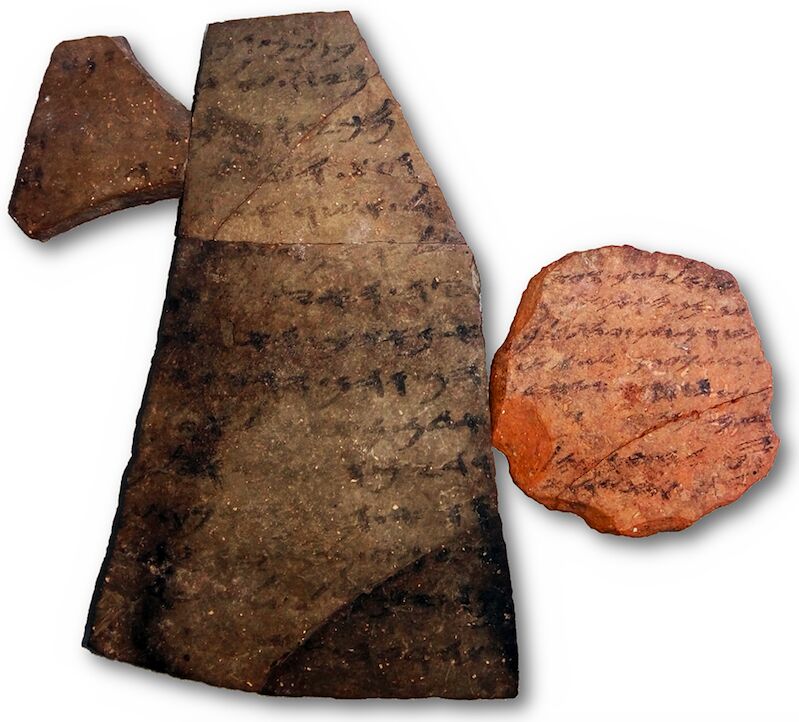

The study, conducted by Tel Aviv University (tau), used a sampling of 18 ostraca (inked pottery fragments) discovered at the Judahite military fortress Tel Arad, dating around 600 b.c.e. Two computer algorithms were used to analyze the ancient Hebrew ostraca to determine how many different hands had “penned” them. And in a unique step, the research team also drafted a forensic handwriting specialist: a 27-year veteran of the Israeli Police Force’s Forged Documents Laboratory and Crime Investigations Unit, Yana Gerber.

The results were surprising: The 18 inscriptions had been written by at least 12 different individuals.

Two Algorithms Vs. Two Eyes

Tel Arad is a small military fortress located in the Negev desert, some 10 kilometers southwest of the Dead Sea. Archaeologists believe it probably only housed some two dozen soldiers. During excavations in the 1960s, a hoard of ostraca, containing various military correspondence, was discovered.

In 2016, the ostraca were analyzed by two computer algorithms, which concluded that they were written by four to six different individuals. This year, the tau team set about to reanalyze the inscriptions with refined algorithms—and compare the computer results to the human touch, with the employ of a forensics expert.

The computers returned similar results, determining between four to seven authors with high probability. Yana Gerber, however, was able to determine at least 12 different authors.

Her expert eye was just what the team was looking for. The computer algorithms, after all, had been based on the most cautious of parameters, only taking into account the most obvious of writing changes, and in some cases refraining from definite conclusions. Gerber, on the other hand, was able to parse out much more minute details. “This study was very exciting, perhaps the most exciting in my professional career,” she stated.

The conclusion surprised the experts. Twelve different authors—among only 18 ostraca—and at such a small isolated outpost? “Since we found at least 12 different authors out of 18 texts in total, we can conclude that there was a high level of literacy throughout the entire kingdom,” stated Dr. Barak Sober, a mathematics expert on the tau team. He went on to explain the significance of the discovery:

The commanding ranks and liaison officers at the outpost, and even the quartermaster Eliashib and his deputy, Nahum [individuals mentioned in the ostraca], were literate. Someone had to teach them how to read and write, so we must assume the existence of an appropriate educational system in Judah at the end of the First Temple period. This, of course, does not mean that there was almost universal literacy as there is today, but it seems that significant portions of the residents of the kingdom of Judah were literate. This is important to the discussion on the composition of biblical texts. If there were only two or three people in the whole kingdom who could read and write, then it is unlikely that complex texts would have been composed.

The tau findings were met with some surprise among the academic community. (Indeed, their findings in 2016 were met with the same reaction—when only four to six different authors had been identified!) Ancient Judah—evidently not some backwater territory—but a generally literate kingdom?

But should the conclusions really have been so surprising? Not for those who know their Bible history.

Reading and Writing in the Bible

The Bible, of course, has much to say about writing and reading. But let’s zero in on the general timeframe at hand—around the seventh to early sixth centuries b.c.e., during the operation of the Tel Arad fortress. Does the Bible say anything about literacy during this period?

The Bible describes prophets reading and writing (2 Chronicles 26:22; Jeremiah 51:60; Daniel 5:25; etc). It describes kings and princes reading (2 Kings 19:14; 2 Chronicles 34:30; Jeremiah 51:61). It describes priests with the ability to read (Jeremiah 29:29). It refers to the “house of Israel,” and Israelites in general, as having a capacity to read (Ezekiel 43:11; Habakkuk 2:2). And it describes children having a basic ability for writing and mathematics (Isaiah 10:19). In fact, captive Israelite children were specifically sought out by the king of Babylon for their “wisdom,” “knowledge” and “understanding [of] science” (Daniel 1:4; King James Version).

Of course, that does not mean everyone, at all stages of Israelite history, had the ability to read and write. Evidently, there was an educational system but not all were fully educated—Isaiah 29:11-12 attest to certain “unlearned.” But it is apparent from the above scriptures that there was a general, widespread literacy among the people of Judah and Israel.

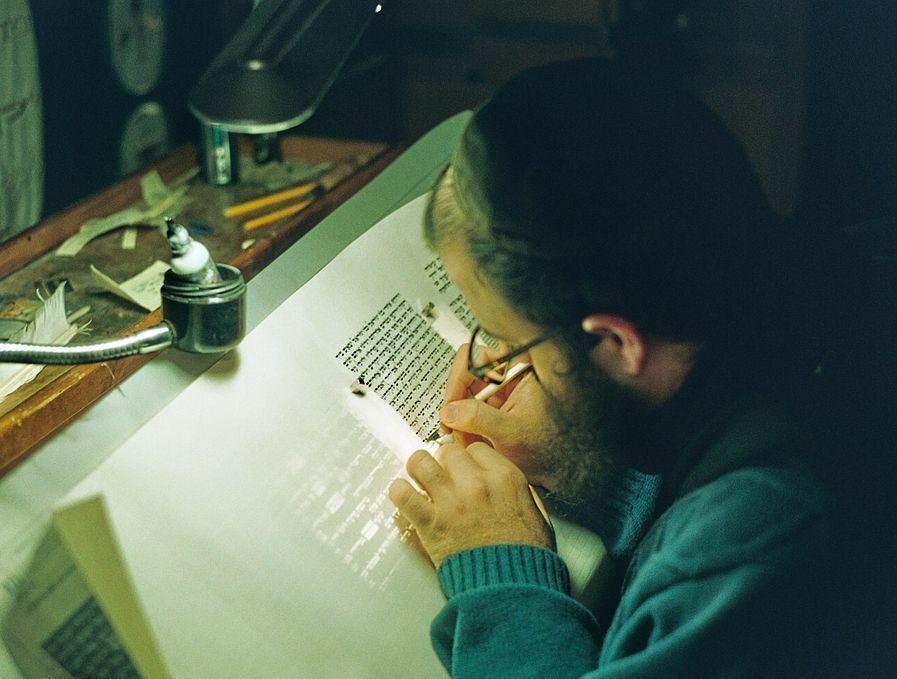

And should ancient Jewish literacy be surprising? After all, the Jews are known as the “people of the Book.” Even the New Testament describes the Jews as specially chosen in relation to literacy—to carefully preserve the Scripture of the Old Testament (Romans 3:1-2; kjv). And it is certainly a task that has been carried out with incredible precision to this day, with “sofers” agonizing over every letter stroke—and the unchanged nature of the Scriptures over the course of thousands of years is a historical marvel.

Of course, this work has been carried out by specially educated scribes—modern “sofers” must be properly trained in order to properly write out by hand, unblemished, all 304,805 letters of the Torah onto an animal skin parchment with simple quill and ink. (A single Torah scroll takes roughly a year to finish—small wonder, then, that they cost around $30,000 each—and some even double that!) Likewise, anciently, scribes were employed in the kingdom of Judah to write and process official correspondence. But the existence of biblical Judahite scribes in no way meant a lack of literacy. (Sir Winston Churchill had a secretary type up his thoughts—it doesn’t mean he was illiterate.) Such scribes were particularly skilled in writing, administrative work and even translation (e.g. 2 Kings 18:26). But skills such as these—and so heavily emphasized in Jewish culture and history—do not happen in a vacuum of illiteracy. As the Scriptures make clear, and as the archaeology now reveals, there was a general emphasis on the importance of literacy in ancient Judah.

Why?

‘That It May Be for the Time to Come …’

Archaeologist Israel Finkelstein, who helped direct the tau research team, stated the following about their findings in relation to the composition of the Bible:

There are different opinions regarding the date of the composition of biblical texts. Some scholars suggest that many of the historical texts in the Bible—from Joshua to 2 Kings—were written at the end of the seventh century b.c.e., that is, very close to the period of the Arad ostraca. It is important to ask who these texts were written for. According to one view, there were events in which the few people who could read and write stood before the illiterate public and read texts out to them. A high literacy rate in Judah puts things into a different light.

Evidently, the biblical texts weren’t intended to be merely spoken to an illiterate public. Instead, according to Professor Finkelstein, they were meant to indoctrinate a literate public: “Whoever wrote the biblical works did not do so for us, so that we could read them after 2,600 years, they did so in order to promote the ideological messages of the time” (emphasis added).

But this theory is diametrically opposite numerous biblical assertions—and is at the heart of the importance of ancient Jewish literacy.

The Prophet Isaiah was commanded to “write it [his prophecies] before them on a tablet, and inscribe it in a book”—why?—“That it may be for the time to come for ever and ever” (Isaiah 30:8). God gave the same instructions to the Prophet Jeremiah, to write down the prophecies to preserve them for future generations. “Write thee all the words that I have spoken unto thee in a book”—again, why?—“For, lo, the days come …. In the end of days ye shall consider it” (Jeremiah 30:1-3, 24).

The Prophet Daniel didn’t have a clue what he was writing about—he said as much (Daniel 8:27; 12:8)—but he wrote it down nonetheless, under the instruction that “the words are shut up and sealed till the time of the end” (verse 9). The Prophet Ezekiel was told to address his message to the “house of Israel,” but Ezekiel had been taken captive and Israel had already been conquered, deported and scattered by the Assyrians. Was his message intended merely to “promote the ideological messages of the time”? Certainly not. His book was also addressed to end-time Israel.

The future-focused nature of the Scriptures was recognized centuries later at the time of the writing of the New Testament: Paul wrote that the events of the Torah were “written for our admonition, upon whom the ends of world are come” (1 Corinthians 10:11; kjv).

As the very scriptures of the seventh to sixth century b.c.e. period bring out, writing is the reliable way to preserve knowledge for the future. Why is it that we know virtually nothing about the thousands of years of human history across Africa, Oceania or much of the Americas? Because of a lack of written material, a lack of literacy, a reliance on patchy oral transmission. No dates. No genealogies. No certainty of events. And no future road map.

The significance of literacy in ancient Judah cannot be underestimated. After all, our Western world was built upon it—upon a Judeo-Christian foundation—with the Hebrew Scriptures as the foundational text. And is it just coincidence that the Western nations are the most wealthy, developed, advanced, prosperous nations in the world? Other civilizations have been tried, based on their own “holy” foundational texts. How about the “experiment” of the last century—the Communist “civilizations” based on “holy writings” like Das Kapital, The Communist Manifesto, Mao’s “Little Red Book”? In the 100-year period from 1917 to 2017, Communism is estimated to have caused the deaths of up to 120 million people. That’s more than the number killed in all the wars of the 20th century—including World Wars i and ii—combined.

It makes you wonder what our world today would be like were it not for our foundational Scriptures—were it not for the literacy of the ancient Judahites. Were it not for the available education received by Tel Arad quartermaster Eliashib and his deputy, Nahum.