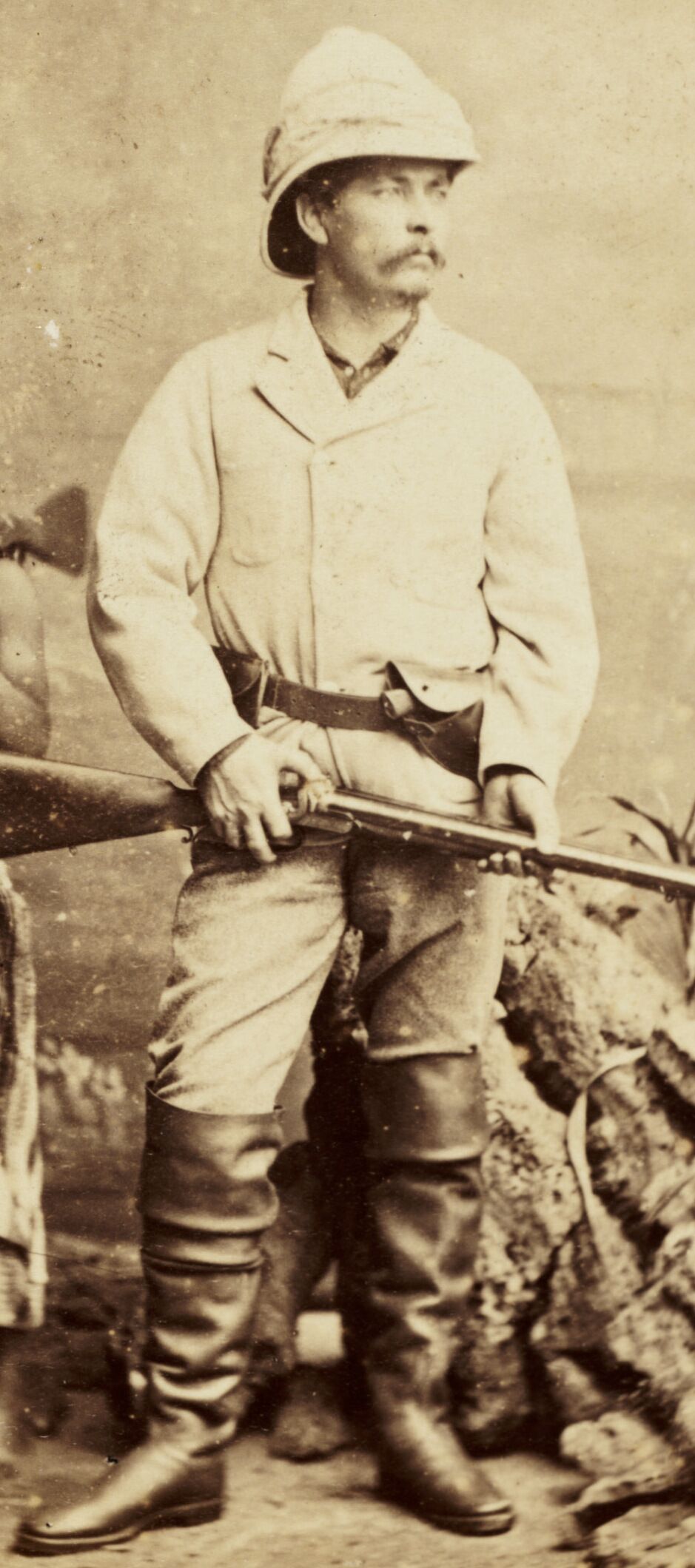

Sir Henry Morton Stanley was one of history’s greatest explorers. The 19th-century adventurer is best known for his expedition into Tanzania to find Dr. David Livingstone—an odyssey that culminated in his famously reported words upon their meeting: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” Stanley’s successful search for the isolated doctor was the first big break of his remarkable career, instantly catapulting him to fame. But upon returning from this outstanding success in the African wilds, he was met with a frosty reception by the British scientific establishment.

Having recently read of this account in a biography on Stanley, I was stunned by the similarities with another extremely successful scientist and a very good friend of mine: Dr. Eilat Mazar. Both individuals have accomplished outstanding feats in the realm of their respective sciences—yet have been met, in many ways, with the same surprising reception from their academic peers. Their stories reveal a lot about academic jealousy and conceit, and are a warning against presumptuously dismissive, scholarly naysaying.

A Life-Threatening Mission

Tim Jeal’s biography Stanley—The Impossible Life of Africa’s Greatest Explorer is an exhaustive new reassessment of the life of this famous, yet much-misunderstood, Victorian explorer. He paints a vivid picture of Stanley’s first mission to the African interior.

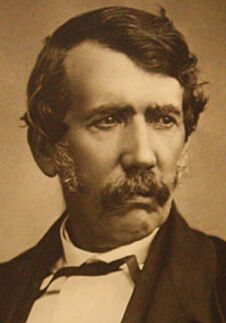

Dr. David Livingstone was a world-renowned African explorer working for the British Royal Geographic Society (rgs). He spent much of his life attempting to find the source of the Nile River (among other endeavors), deep within uncharted Central Africa. The exploits of this pioneering white explorer in hostile territory gripped the Western world. However, by 1871, nothing had been heard from the man in nearly two years, and next-to-nothing in six. He was believed to have crossed into cannibal territory, and no one knew where he was or even if he was still alive.

Henry Morton Stanley, a Welsh-born journalist for the New York Herald, had been an ardent follower of Livingstone. He persuaded his employer to fund an expedition to find and provide relief for the doctor—a mission that, if successful, would become a newspaper scoop without parallel. The editor agreed and Stanley, 30 years old (having traveled the Middle East but a complete novice to Africa), set out in March 1871 with over 100 men (mostly native porters) into the African heartland.

The journey to find Livingstone would take eight months of grueling travel. The expedition was plagued by desertions, malaria, dysentery, smallpox, fever, delirium, hostile tribal encounters and the death of many pack animals. Some few of Stanley’s men perished along the way. As if that weren’t enough, the convoy got caught up in a large regional conflict, joining the fight alongside an Arab trading army attempting to repel a warlord and his large force of cannibal mercenaries.

Finally, the expedition arrived at the small, remote village of Ujiji where to their jubilation, they found Livingstone. The relief effort had come just in time—the 58-year-old was deathly ill. He had narrowly escaped being murdered, his supplies had been pillaged, and he had hardly any food. His rgs supplier had willfully neglected to deliver his designated supplies to Ujiji (instead, spending significant time “holidaying”). Livingstone had been let down, to the point of death, by the rgs.

Stanley’s team stayed with the doctor for about four months, nursing him back to health and carrying out a small expedition with him. Unable to persuade Livingstone to return with them, Stanley finally returned to the Tanzania coast with his men, ensuring that Livingstone was well supplied with food and porters. He then sailed on to England with what was the greatest journalistic story of the century—in fact, one of the greatest feats of journalism in all history—to receive a hero’s welcome.

A Surprising Reception

Stanley’s triumphant return soon turned quite sour. He was immediately shunned by the British establishment, who were extremely “jealous” of his expedition. The Royal Geographic Society, upon Stanley’s return, was about to send out a relief party of its own. (They had heard about his mission earlier on, and had the “uncanny” idea to form their own rescue team.) A shocked Stanley was told that the rgs “didn’t want you to find him.” They became offended by Stanley’s public criticisms of their supplier, Dr. Kirk, who had starved Livingstone of his supplies and sent him rogue and expensive porters who worked against him.

Elements of the press turned against Stanley—some even started a vicious conspiracy theory that Stanley had never actually met Livingstone but had faked the journey. This was disproved—still, the damage was done. “The general opinion is that I am a fraud,” Stanley wrote.

He was mocked for his motivation for finding Livingstone and was accused of “sensationalism.” He was cold-shouldered by the rgs, with its president, Sir Henry Rawlinson, contemptuously suggesting that “if there has been any discovery and relief, it is Dr. Livingstone who has discovered and relieved Stanley.” (As an aside: Rawlinson is famous in the archaeological world, known as the “father of Assyriology” for his work in deciphering cuneiform inscriptions.) Finally though, Rawlinson felt pressured enough to send Stanley a curt letter of thanks from the Society.

As Stanley wrote:

[My accomplishments] have been strongly colored by the storm of abuse and the wholly unjustifiable reports circulated about me. … So numerous were my enemies … I had to resort to silence as a protection against outrage.

Even Dr. Livingstone and his methods were not safe. Stanley was surprised to hear the ready derision by the rgs of their aging African explorer, accusing him of “insanity” and “irritability,” and laughing at his misfortunes. In a public geography convention, one upper-class speaker after another tore into Livingstone’s theories about the source of the Nile. Stanley too had his doubts, yet he stood up and condemned the rgs elites as “easy chair geographers,” vociferously defending the doctor’s record of putting theory to the test in 30 years of grueling African travel.

Stanley’s methods were also criticized. Ordinarily, he would have been awarded the rgs gold medal for his expeditionary work. The Society’s secretary attempted to disqualify him unfairly on technicalities. Stanley leaked the secretary’s letters to the public—and ended up receiving the gold medal.

See, despite the official snobbery and cold-shouldering by jealous scholars and elites, the general public was enraptured with Stanley and his daring rescue mission. He was instantly famous. His book, How I Found Livingstone, became a runaway bestseller. Regarded as a hero, Stanley was given major press interviews, and even Queen Victoria gave him an audience and an award.

In reading the account of Stanley’s reception, several elements struck me for their familiarity. Dr. Eilat Mazar, whom I have worked with on several occasions in Jerusalem, has experienced similar criticism from those in the same old, cold scientific establishment.

A Jerusalem Expedition

Dr. Eilat Mazar is best known for her archaeological work in Jerusalem. She is famous in the field, known not only for her stunning finds but also for the sheer quantity of them.

Monumental discoveries include the palace of King David, a gigantic Solomonic-era gatehouse and tower, an enormous Solomonic wall, and a portion of Nehemiah’s wall. The many small finds include the personal seal stamps (bullae) of King Hezekiah and Isaiah the prophet; bullae belonging to the two biblical princes and enemies of Jeremiah, Jehucal and Gedaliah; the oldest piece of writing ever found in Jerusalem; the earliest alphabetical inscription found in Jerusalem (and possibly in all Israel); the largest vessels ever discovered in Jerusalem; possibly the largest Year 4 Revolt coin hoard ever discovered; and one of the three largest gold hoards ever discovered in all Israel—certainly the most famous of them—made most notable by including a large gold medallion bearing the Jewish symbols of a menorah, shofar and Torah scroll. Added to her vast experience excavating Jerusalem (starting as a young girl, she assisted in her grandfather’s excavations), Dr. Mazar specializes in Phoenician archaeology, notably excavating Phoenician tombs.

Dr. Mazar herself has been stunned by the sheer number and impressiveness of the discoveries. She admits that most archaeologists only ever discover a small percentage of what she has been privileged to find. Given all of her incredible discoveries and vast experience, one would think Dr. Mazar would be about the most highly esteemed archaeologist in Israel, admired by students and contemporaries. In fact, in many ways, just the opposite is true. As Henry Morton Stanley experienced, a significant chunk of Israel’s archaeological establishment has been very much against her.

She has been condemned for “sensationalism.” Her methods have been criticized as hasty and biased. She has been accused of forcing an “agenda” into her finds, some even suggesting foul play in the discoveries, or at least dismissing them as unimportant. Haaretz, the far-left Israeli news outlet, has faithfully reported negatively of her. “In archaeological circles, Mazar is practically a one-woman camp of her own,” writes their archaeology correspondent Nir Hasson, condemning her as a “far-right” fringe. Let the Stones Speak assistant managing editor Brent Nagtegaal joined her in Tel Aviv at an archaeological conference. In an occasion resembling Stanley’s speeches before members of the geographic committee, Brent related the following:

… I accompanied Eilat to an archaeological convention in Tel Aviv. She was releasing her recent discovery of Nehemiah’s wall to a standing-room-only crowd of hundreds of people. This event—a scholar from Hebrew University in Jerusalem walking into liberal Tel Aviv University—was as close as I’ve gotten to high-noon showdown in Dodge City. Immediately following Eilat’s presentation, the next professor got up; instead of using his time to show what he had discovered, he used all of it to discredit Dr. Mazar’s work. I was incensed at some of the preposterous claims ….

Why such a hostile reception? Herschel Shanks, then editor of Biblical Archaeology Review magazine, wrote (emphasis added):

No one would question her professional competence as an archaeologist [actually, some have tried]. Her chief sin, however, is that she is interested in what archaeology can tell us about the Bible … making a reasonable judgment about archaeological evidence as it relates to the Bible. In some scholarly circles this is considered “unscholarly.” If the judgment she made related to something other than the Bible, no one would give it a second thought. Only a finding related to the Bible brings such obloquy down on the head of a leading archaeologist.

The thing is, Dr. Mazar actually considers the biblical text when undertaking her archaeological work. This “sin” is anathema, maddening to the scholarly establishment. According to them, she shouldn’t be making biblical discoveries, because the Bible is false. They criticize her for actually finding what she is looking for (in spite of the fact that it is actually good science—sign of a good theory—to find what you are looking for).

As Brent wrote of the above-quoted Haaretz journalist Hasson, he (in this article) “sought to discredit the findings of Dr. Mazar, painting her as an off-the-wall archaeologist who cannot be trusted since she keeps making biblically significant discoveries.” Her detractors simply can’t understand why, in the land of the Bible, Dr. Mazar keeps on making astounding, biblically significant discoveries. Perhaps it’s because she excavates where the Bible says things actually happened? Brent asked, “Why didn’t Hasson go into more depth to understand why Dr. Mazar made such designations [about biblical artifacts]? Instead, he just quoted scholars who are openly hostile to the Bible—and whose careers are underwritten by such a contention.” That’s the thing—many an elite archaeologist’s career is built upon undermining the biblical account, propounding their own theories even contrary to the evidence. Talk about bias.

Is Dr. Mazar religious? No. In fact, the case could be made that her contemporaries harbor more religious fervor against the Bible than she has for the Bible! The fact is, the Bible is a book of history. For archaeologists and historians trying to understand Greece’s past, it is helpful to have a good knowledge of Herodotus and Homer. For Ireland, the Lebor Gabála Érenn. For Egypt, Manetho. And surprise, surprise, for Israel—the Bible! As such, Dr. Mazar uses the Bible as one of her chief tools in understanding ancient Israel’s past. She realizes that to ignore such a valuable work would be ludicrous.

Actually, archaeological scholars weren’t always so hostile. It has only been in the last several decades that there has been a virulent pushback against anything Bible-related. It used to be a guiding light in Israeli archaeology. So perhaps you could say Dr. Mazar is “behind the times.” Thus, for a chunk of Israel’s scholarly scientific establishment, she is an aberration that must be crushed.

But for just about everyone else, the “regular Joes,” it is a different story. Dr. Eilat Mazar is deeply respected and loved. Just as the people heaped praise upon Stanley, the same is true for Dr. Mazar. These are people who hold dear, to some degree or other, their biblical history in the land of Israel. They love hearing about Mazar’s sensational discoveries. What are you supposed to do with a circa 700 b.c.e. royal seal impression reading Belonging to Hezekiah, son of Ahaz, King of Judah? Such finds speak for themselves. They have no agenda. The ground yields what it yields. Her “motto” is: Let the stones speak. What about the criticism she receives, because her funding comes from Jewish and Christian sponsors? Mazar responds: “Well, the stones, and the structure, and the stratigraphical layers—they don’t care who is giving the funds.”

As for archaeological method—I’ve worked with Dr. Mazar, and she is exceptionally careful and methodical. On our latest excavation, one of the employees mentioned the same thing: comparing just how much more meticulous Mazar’s excavation was compared to another one she had participated on.

Dr. Mazar welcomes different opinions, criticisms—looks for them even, touring her most vocal critics around the dig site. She likes to consider all options to arrive at the very best conclusions. That’s not to say the criticisms aren’t wearying. But she is incredibly resilient. And her conclusions are carefully and methodically considered. Just look at the Hezekiah bulla—only released to the public six years after being excavated. The Isaiah bulla was released eight years after. And if she’s presented sufficient contrary evidence, she’ll change her conclusion. If only the same could be said for the Bible-bashing critics.

No one can criticize her work ethic. It’s like Stanley called the rgs members of his day—“easy chair” critics, passing judgment from the comfort of their air-conditioned offices many miles away about subjects they don’t fully understand in places they have never been. Mazar is in her 60s, but she is still hard at work either out in the field or in her cramped university office. She’ll reply to e-mails at any hour of the night—who knows when she sleeps. She’s out there early to the excavation site, often buttoned up in a Hi-Vis jacket directing traffic, while the crane and dump truck remove excavated sacks of earth and rocks. She was doing the very same thing the night before the big release of the Isaiah bulla:

I was helping her that night, working on the truck with the contracted crane operator. He went on and on, talking to the dump truck driver about how awesome Dr. Mazar is, and all of her incredible finds. People just love her work! Brent related the same phenomenon:

There were the many times when we would leave the dig site together in her car, crawling through the epic congestion of Silwan, the predominantly Arab village that sits on the location of the ancient City of David. Every time we came to a stop for a brief moment, she’d be talking out her rolled-down window to some local as he walked past, or yelling to another as he sipped his Turkish coffee from a rooftop overlooking the road. At first I thought she was just being friendly with strangers. But then I overheard them calling her Eilat. Whether Arab or Jew, these City of David inhabitants all knew her. What amazed me further is that she knew them: She had worked with many of them or their family members over decades of excavation on that same hill. In this most volatile neighborhood on the planet, here was one lady who had the respect of them all.

There’s the Arab custodian at the Hebrew University, whom Dr. Mazar always converses with in her (limited!) Arabic. There’s the King David Hotel security guard (at our big exhibit launch of the Hezekiah and Isaiah bullae), who starts gushing about her when he sees her pulling into the parking lot in her clapped-out van, quickly shepherding her into his best parking bay. As Stanley was congratulated by the Queen, so too (on a smaller level!) has Dr. Mazar herself been personally commended and congratulated by her own nation’s leaders. Both Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and President Reuven Rivlin have personally congratulated her on her work and the significance of her discoveries. The stories could go on. They are a testament to the real impact she has made, not only to the field of archaeology, but also on people’s lives.

Hope for the Future?

After Henry Morton Stanley’s book became a major bestseller, the once-vindictive leaders of the Royal Geographic Society put on a large banquet in his honor. At that banquet, rgs president and Assyriologist Sir Henry Rawlinson delivered a profound apology to the man who had risked everything to find their long-lost explorer. So earnest was the speech that the American writer Mark Twain, who was at the event, said it was “the most manly and magnificent apology … that I ever listened to.”

Perhaps one day—as genuine, sensational biblical discoveries continue to flow in—the same could be said for Dr. Eilat Mazar.

To read more about our organization’s special 50-year relationship with the Mazar family in uncovering Jerusalem’s history, take a look at our article “An Iron-Bridge Partnership.”