Biblical Names Confirmed Through Archaeology

It’s a classic question in biblical archaeology: Can this biblical individual be verified through archaeological means? And the past two centuries of archaeological discovery have yielded up an incredible amount of evidence. So far, at least 53 people described in the Hebrew Bible have been confirmed through stringent analyses (as documented by Prof. Lawrence Mykytiuk here, along with another 13 listed as “probables”).

For this article, I intend to focus not on the people, but simply the names. Much debate rages over whether or not a certain discovered name matches a specific biblical individual. Many factors have to line up. The name has to date to the right period. It may be required to match the right location and general historical description. Generally, a genealogical link—i.e., a father’s name—will be a key piece of evidence.

But what about just the names? The Bible is full of names for different people of different periods. Thus, if archaeology can corroborate names for the right periods, then that would serve as proof in its own right of the accuracy of the biblical record.

The First People

The first man listed in the Bible is Adam. No archaeological proof of his existence has yet been found. But what, simply, of his name? Surely such an important and central individual’s name would have been used in very ancient history.

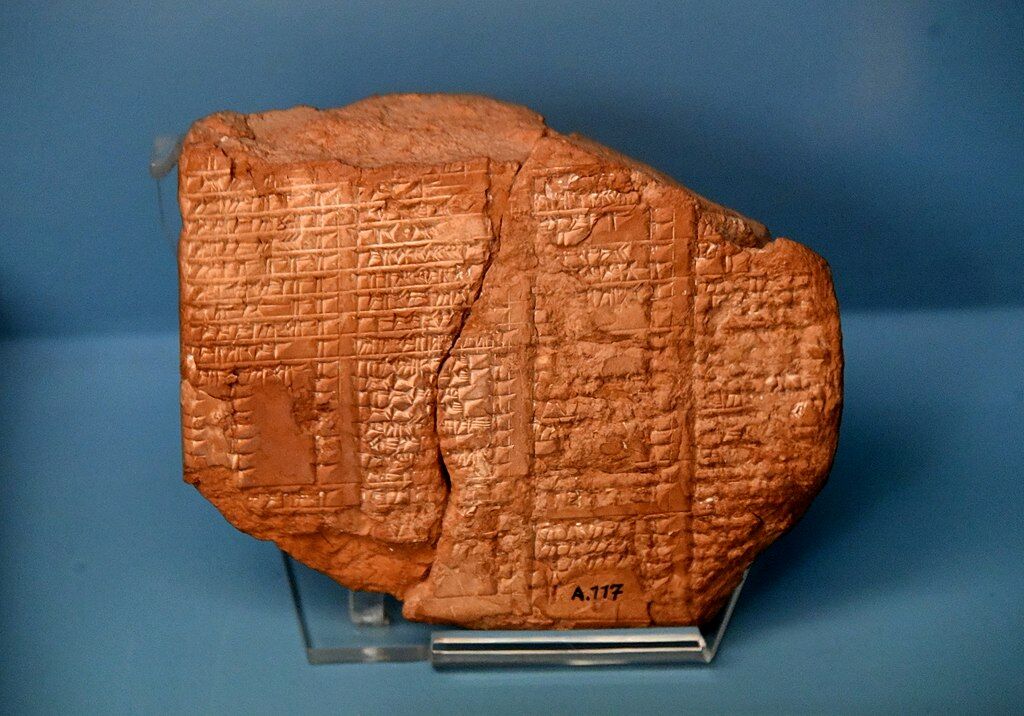

And it was. The name Adam is attested to in a couple of notable early national histories. One example is on the Assyrian King List. This list is known from tablets dating back to the 11th century b.c.e., but even these copies are known to have come from an earlier original source compiled c. 1800 b.c.e.

The name is listed, in the slightly different Assyrian form, as Adamu, second ruler of Assyria. While nothing is known of his reign, it is speculated that he ruled around 2400 b.c.e. Historian and Egyptologist David Rohl has put forward that this figure could even be the biblical Adam himself. This is because the name of the very “first” king, Tudiya, is placed on the list directly before Adamu, i.e. “Tudiya Adamu.” If the word “Tudiya” is taken as a verb rather than a personal name, we have the phrase “Beloved of god, Adam.” Rohl believes that the two words describe one and the same individual. Evidence for this can be found on a later Babylonian copy of the king list, in which the two names appear to be joined together in a heavily corrupted form: Tubtiyamutu.

Whether or not Adamu is a reference to the Adam of the Bible, the Assyrian king list clearly proves the name to be among the earliest in human history.

Further evidence of the use of “Adam” can be found in Egypt, among its pantheon of gods. This specific god was worshiped very early in Egypt’s history (c. 2500 b.c.e., if not earlier). According to the Heliopolis creation myth, he was known as the “first god and living being.” His name? Atum. (Linguistically, “t” and “d” sounds are readily interchangeable, especially cross-culturally.) This “first being” Atum emerged from a chaotic state of darkness and a primordial watery abyss. This brings to mind biblical description of the world before the creation of man: “And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters” (Genesis 1:2; King James Version).

The biblical Adam’s third son was named Seth. Interestingly, the Egyptian Atum’s great-grandson was also named Seth—further proof for the authentic, early nature of these names.

As for Eve: Adam named her this “because she was the mother of all living” (Genesis 3:20). The ancient Sumerians, an early culture that only ended around 4,000 years ago, wrote of an early being named Enki who succumbed to an illness in many of his organs, including specifically his rib (curiously, this illness came from eating “forbidden flowers”). For each afflicted part of the body, a female being was born. In order to heal the rib, a female named Ninti was born. “Ninti” means Lady Rib—a clear connection to Eve.

The name Ninti is especially notable, as it has a dual meaning—not just Lady Rib, but Mother of the Living. The Sumerian word for rib, “ti,” is synonymous with life. As such, Ninti was specially known as the “goddess of life.” Ninti is also called the “One Who Makes Live.” So while the Semitic name “Eve” is not used by this foreign culture, still a name giving the equivalent meaning is.

There are a number of other early recorded individuals, with either names that are either parallels or near-parallels to the earliest biblical figures. Individuals such as Tuvalcain, Jubal, Javan and Nimrod (see the links for more information).

The Age of the Patriarchs

The patriarchs have long been a point of contention for the critics. Neither Abraham, Isaac, Jacob nor their wives have been confirmed through archaeological discoveries. According to archaeologist and professor William G. Dever, by the start of the 21st century, archaeologists “had given up hope of recovering any context that would make Abraham, Isaac or Jacob credible historical figures.”

Of course, to take that position is to ignore a slew of evidence backing up the biblical description of the patriarchal age. Sure, the individuals themselves haven’t been confirmed—looking for direct archaeological proof of 4,000-year-old, oft-nomadic individuals is a challenge, to say the least. But pretty much the entire biblical setting of the early second millennium patriarchal age has been shown to be accurate, right down to the laws, customs, clothing and even phraseology used. You can read more about that here and here.

And again, something can be said for the names.

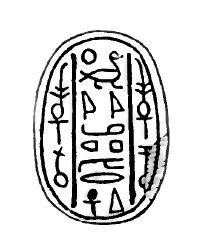

Jacob is a well-known name of Semitic origin. And there is evidence linking the name to Egypt.

The Bible describes how Joseph became second-in-command under the pharaoh. After Joseph’s extended family moved into Egypt, his father, Jacob, pronounced a blessing on the pharaoh (Genesis 47:10). Jacob must have been given great honor within the country, considering the fact that the Egyptians mourned his death for 70 days (Genesis 50:3). A number of archaeological excavations have uncovered 27 royal scarabs bearing the name “Yaqub-har,” or “Yacob-har” (“Jacob” is the anglicized form of this original name). These scarabs were found most notably in Egypt and Canaan, showing a tie to the Promised Land (where Jacob had lived for most of his life). Was this Yacob the same figure as the biblical Jacob? It is probable. The “Yaqub-har” scarabs haven’t been conclusively dated, but could point to Jacob’s time or just after. The “har” part of the title is a word meaning hill, mount or mountain in Hebrew—a word connected with Jacob several times in the Bible (e.g. Genesis 31:25, 54; Isaiah 2:3, 41:14-15). The phrase would thus mean “Jacob’s Mount.” Whether or not this is the biblical Jacob, these scarabs confirm the early use of the important patriarchal name in both Canaanite and Egyptian contexts.

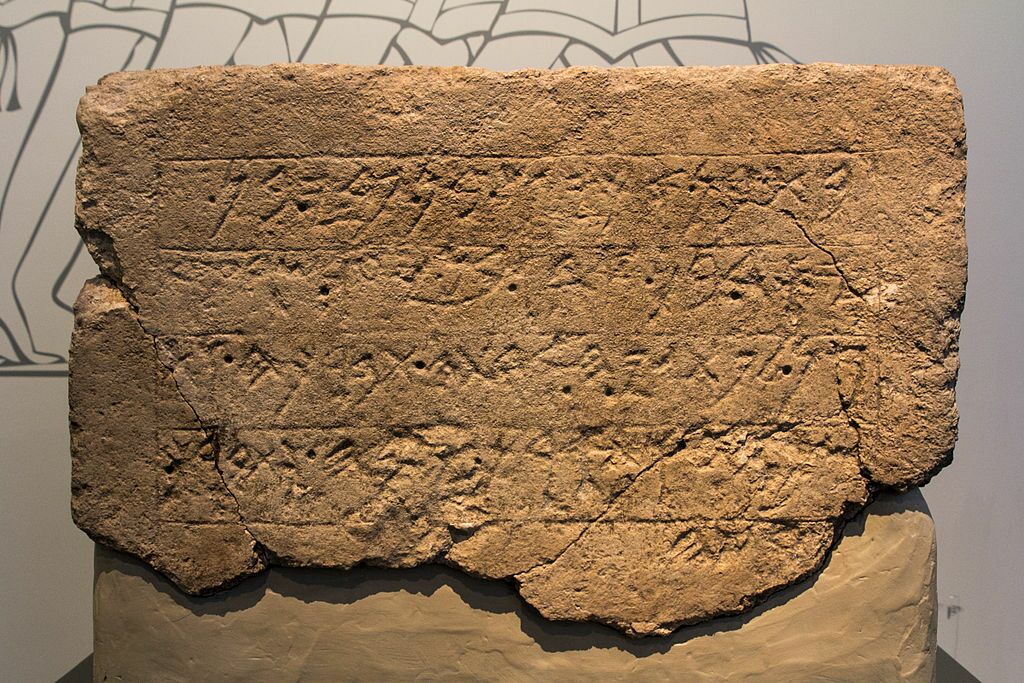

Partway through Jacob’s life, God changed his name to Israel (Genesis 32:28). This became the national name taken on by his 12 sons. The earliest as-yet discovered references to “Israel” apply to the nation, rather than to an individual—still, they confirm the early national nature of the name. One artifact, the Merneptah Stele, dates to the 13th century b.c.e.; the other, the Berlin Pedestal, is of an uncertain date, but may have been created as early as the 15th century b.c.e.

Egyptian Captivity and Exodus

Then there’s the name Moses. Moses is one of the most significant figures in traditional Judaism. Critics blast the fact that the individual himself hasn’t yet been discovered in archaeological context. But again, much can be said of the story’s setting and even of his name.

According to traditional dating, Moses would have lived through the best part of the 15th century b.c.e. He was famously found in a floating basket, adopted, and named “Moses” by an Egyptian princess, “Because I drew him out of the water” (Exodus 2:10; click here for parallel evidence for this account). As it turns out, Moses—interchangeably Mosis, Moshe or Mose—was an important name element in royal Egyptian society, dating primarily to right around the 15th century b.c.e.! The name Moses means, in Egyptian, born of—again, just as is inferred in the above-quoted scripture. Moses may have had a longer name to represent the full phrase “born of water.” This was the case with his contemporaries, such as Tuthmose or Tuthmosis (“born of Tuth”), Ahmose, Amenmose, Ramose, Kamose, Wadjmose (etc, etc). Again, all these name types are from the same period—contemporary with Moses. So it would only make sense for a princess of the royal “-mose” family to call her adoptive son by the same name.

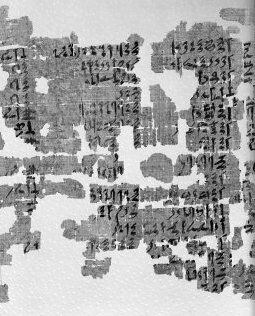

Another famous individual during the period of Egyptian captivity was the midwife Shiphrah. She and her fellow midwife, Puah, were directly advised by the pharaoh to kill all sons delivered by Hebrew women. The women bravely rejected the command.

The name Shiphrah has been found, documented on an Egyptian papyrus slave list. This list dates to the early part of the Egyptian captivity (during the reign of Sobekhotep iii). It is impossible to say whether this woman is the same one mentioned in Bible, but it certainly proves the authenticity of such a name being used among the slave classes during the period of Egyptian captivity. The list, kept by the Brooklyn Museum, also mentions the Hebrew name Menahem, as well as variants of the tribal names Issacher and Asher.

While the point of this article is to show how even generic names support the biblical account, mention should be made here also of the fact that even the omitting of names supports the biblical account. What do I mean? Well, none of the early biblical pharaohs are mentioned by name. This drives historians crazy, especially when trying to determine the pharaoh of the Exodus. But even this simple omission of names confirms the authenticity of the biblical account. Refraining to use the early pharaohs’ personal names was in keeping with the tradition of the period. Pharaohs were referred to by their god-like title—not by their personal names. Later on, after the Exodus, Israel was free of Egyptian captivity and traditions—and from this point on in the Bible, we see a referral to pharaohs by their personal names.

Time of the Judges

The judges period is rather murky, a time of great upheaval. As the biblical book describes, Israel was an oft-disunited, tribal mess repeatedly oppressed by conquering powers or massacring each other. There is a general dearth of names from this period—let alone biblical names. But we’ll consider one.

One of the most significant oppressors during this period was Jabin, king of Hazor. He was eventually overthrown by an Israelite force led by Barak and the Prophetess Deborah (Judges 5).

Up to two centuries earlier, in Joshua 11, we find another Jabin, king of Hazor, on the scene. This has led to some confusion in the accounts and speculation of outright biblical inaccuracy—that these Jabins must have actually been one and the same, and that the biblical timeframe must have been artificially elongated. However (as typically happens), an archaeological discovery has cleared up the debate. According to archaeologist Dr. Douglas Petrovich (emphasis added):

The tension [with regard to the “Jabin” question] dissipates, however, once the reader understands that the term “jabin” is not the name of the king, but rather is a royal, dynastic title. [T]he use of this ancient name dates back to the Mari archives of the 18th century b.c., where Yabni-Adad is mentioned as the king of Hazor [“Yabni” being a Mari form of the Hebrew word “Yabin,” which is then anglicized to “Jabin”]. The proposal of a dynastic use of “jabin” for the king of Hazor in both Joshua and Judges thus has sufficient merit ….

So we see a “Jabin” as king over Hazor during the 18th century, based on the Mari archives; a “Jabin” as king over Hazor during the 15th century, based on Joshua 11; and a “Jabin” as king over Hazor likely during the late 13th century, based on Judges 4. And again, while the early Jabin does not prove the specific, later biblical Jabins, even the simple correct use of the titular term for the ruler of the city of Hazor lends authority to the biblical text.

Israel: The Kingdom Years

This period is the complete opposite of the time of the judges, because so much has been discovered proving various biblical characters and the use of different names. Pick a biblical name from this period and, chances are, it has been discovered in the archaeological record. Besides the generic names, a total of eight kings of Israel and six kings of Judah have been uncovered, alongside numerous figures of lesser rank. Many more are of a “near-proven” classification.

Of course, this only makes sense. During this period the Israelites were well established in their homeland. Thus, excavations occurring within that land, within pinpointed city sites, will readily produce names from this period. The especially tricky periods are generally those when the Israelites were separated from the land.

While there isn’t much point going through the vast amount of parallel names dating to this period, there are several interesting points, particularly relating to the foreign names, that we will highlight.

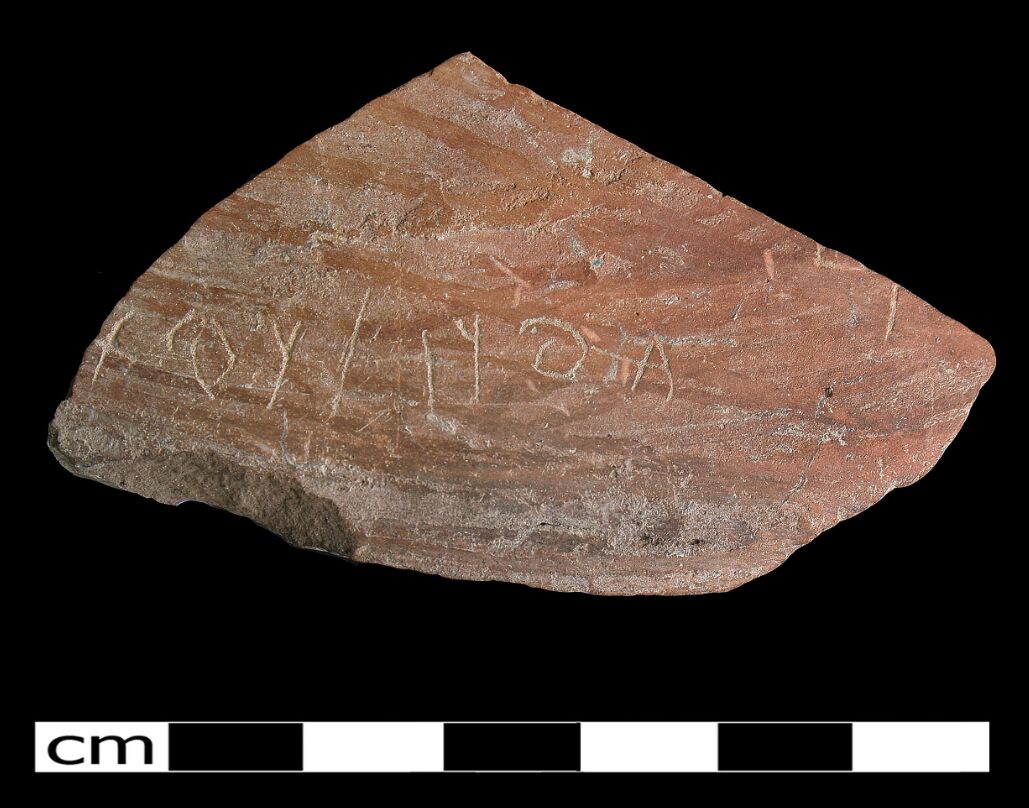

Goliath is a case in point. This individual has not been uncovered in archaeological context, but evidence has been found regarding the authenticity of his name. Two inscribed potsherds have been discovered at Goliath’s “hometown” of Gath, dating to the 10th to ninth centuries b.c.e., making these the earliest Philistine inscriptions ever discovered. They bear two names of linguistic link to Goliath’s—Alwat and Wlt. The Anglicized version of “Goliath” is much different from the original—pronounced in Hebrew as Galyat. These names all show Indo-European roots, rather than Semitic roots like the Canaanite and Hebrew names. This confirms the distant Mediterranean origins of the Philistine peoples and lends support to the biblical accuracy of the story of Goliath, authentic in name.

Achish is a similar example. This is the name of a Philistine king of Gath who lived during the reign of David, as well as a (probably different) king of Gath during the reign of Solomon. A large stone tablet, dating to the seventh century b.c.e., was discovered at Gath’s sister city Ekron. It contained a lineage of five rulers. One of the rulers named is Achish. This must have been a common Philistine name, and like Goliath, Alwat and Wlt, it is not Semitic. Again, while this Achish must have been different from the biblical examples, it still shows the authenticity of the account in using the right name.

King Hezekiah’s treasurer had an unusual name: Shebna. He was an evil, proud man condemned to an ignominious end by God through the Prophet Isaiah (Isaiah 22). It is thought that Shebna may have been behind the effort to turn Hezekiah to the Egyptians for help against Assyria (an alliance evident through archaeological discoveries). Further, it may well have been Shebna who convinced Hezekiah to strip the temple in order to pay tribute to the Assyrians (a receipt of this payment has been discovered).

The name Shebna is believed to be of foreign origin. No discoveries have yet been made with 100 percent certainty confirming this individual; however, there is a tomb lintel inscription that refers to this individual with near certainty, describing a steward’s tomb curse that may parallel Isaiah 22. Unfortunately, most of the name on the tomb has been chiseled out. Still, a seal has been found from Judah’s second-most significant city, Lachish, dating to the same time period (late seventh century b.c.e.), and bearing the same name as the biblical Shebna. This again confirms an accurate period name, even given the fact that it is an unusual, probably foreign name. The name has also been found stamped on clay bullae.

Of course, associating names with the right period is important. Over time, names fall in and out of use. A good example of this is regarding the name element Baal—a reference to the pagan Canaanite god. Saul’s son, for example, was named Ishbaal (1 Chronicles 8:33). The name Ishbaal has been found on a vessel from the Saul–Davidic-era city Khirbet Qeiyafa. While this Ishbaal is a different individual (the individual on the vessel was a son of Beda), it confirms the use of this name for figures belonging to the parallel, early period. Moving into later periods in Israel’s history, names including the term “Baal” fall out of use, likely due to the waning significance of the Canaanite god and the adoption of names incorporating God’s names of -Yah or -El, or pagan deities of other nations.

The Diaspora

Now we come to another difficult period—the time of the exile. Still, even though the Israelites and Jews were uprooted from their lands, a great deal of evidence has been found pointing to where they went and established themselves. Numerous tablets have been found relating to daily Jewish life in Babylonian captivity.

The most maligned diaspora text—in fact, one of the most maligned books in the entire Bible—is the book of Daniel. This is due to the deeply prophetic nature of the book. More detail about this, as well as the huge amount of evidence pointing to an early, original, pre-prophecy writing, can be found here.

Daniel’s three friends, Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, are well-known figures. They famously refused to obey King Nebuchadnezzar’s demands to worship the golden image he had created. As a result, the king threw them into a raging furnace (these have also been verified as a Babylonian form of punishment). The three of them were joined in the furnace by a fourth Being: “the form of the fourth is like the Son of God” (Daniel 3:25; kjv). Nebuchadnezzar called out the three men, who emerged from the flames unharmed. These three friends were given positions in the Babylonian government. As such, it would make sense to find some kind of record of them.

A Babylonian prism has been unearthed, listing a number of officials who served during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar. The list bears possible reference to all three of these friends. And even if they are not the same individuals, the attestation of the names is evidence of general period accuracy in itself. One of the names on the prism is Ardi-Nabu, a direct equivalent to the Aramaic “Abed-nego.” Another name is Hananu—this could be Hananiah, the original name of Shadrach (Daniel 1:7). The third, Mushallim-Marduk, is possibly Mishael, whose name was changed to Meshach (same verse).

What about the book of Esther? The two central figures are Esther and Mordecai. These names seem to be of pagan origin. Esther’s original name was Hadassah (Esther 2:7). “Esther” hearkens to the Babylonian goddess “Ishtar,” and “Mordecai” appears to be linked to the god Marduk. Dating to the reign of Xerxes i, archaeology has found evidence of a number of royal courtiers by the name of “Marduka.” One of these could well have been the very same Mordecai, whom the Bible says also served in some manner in the king’s palace (verses 5, 11) and “sat in the king’s gate” (verse 19).

Xerxes i is generally believed to have been the biblical king Ahasuerus, who married Esther. Xerxes had a wife known as Amestris, or Amastri—the jury is still out as to whether this could have been the same woman as Esther (given the parallel end element, estris). Esther, Ishtar, -estris; Mordecai, Marduka—all evidence of an accurate biblical depiction of the period.

What about the books of Ezra and Nehemiah? Three significant leaders stood in opposition to the reconstruction of Jerusalem: Sanballat the Horonite, Geshem the Arabian, and Tobiah the Ammonite. Sanballat has been conclusively proved through archaeology. Geshem has been pinpointed with near certainty; however, there are still two possible candidates for this individual: Geshem or Gashmu, and Gashm (the first one is more likely than the second), so we cannot yet be 100 percent certain. And though Tobiyah has not yet been uncovered, the name is well attested to, such as in the Lachish Letters (dating to the century prior to Nehemiah). Again, whether the individuals are conclusively verified or not, the names certainly fit.

God’s Names

So far, we’ve only covered the names of various persons. What about the names of God? These too have been seen clearly through the ancient texts. If the Bible is to be our guide, the core names of God were present right from the beginning. But given that the history of mankind is almost exclusively pagan, we can expect to find those names corrupted or misappropriated to various other deities. Again, though, the purpose of this article is to simply show the early use of the names.

There are multiple names used for God in the Bible. One is yhwh, sometimes translated as Yahweh or Jehovah (the true pronunciation of the name has been lost). This name has been found on numerous early Hebrew artifacts dating to the kingdom period (many of these referring, of course, to the true God). The earliest confirmed extra-biblical Semitic use of the term dates to c. 840 b.c.e.—the Mesha Stele describes taking from the Israelites “the vessels of yhwh.” However, the use of the name has also been found much earlier in Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions, used in reference to Semitic peoples. These inscriptions date as early as the 1400s b.c.e.

Other names, including similar parallels of El and Yah, have been found dating to around this period or even earlier contexts.

One interesting point, from a dating perspective, is a term used for God in the book of Daniel. Again, many scholars try to date the book of Daniel as late as possible in order to avoid his prophecies about the Babylonian, Medo-Persian, Greco-Macedonian and Roman empires. (This only goes so far though—the earliest discovered copies of Daniel date to the second century b.c.e., long before the fulfillment of Daniel’s prophecies regarding the Roman Empire. Thus, scholars are forced to date this book to the Maccabean period at the latest. You can read here for further information on the vast amount of evidence proving a much earlier, original date for the writing of Daniel.)

One of the proofs of an early date for the book of Daniel is his use of the term Lord of Heaven. Here again, evidence speaks to the authenticity of the biblical record—this name was only used during earlier periods (such as when Daniel would have written his book, in the sixth century b.c.e.), and actually fell out of use during the later, zealous Maccabean period. This is because the term had come to be associated with the pagan Greek god Zeus.

Generic Names—Broadening the Perspective

In this article, we’ve only touched on a small number of personal names—and how that even though they do not “prove” a specific individual, they still—in their own right—prove the authenticity and accuracy of the biblical account, showing accurate settings and time periods. Exactly the same process could be applied to place names, as well as to early tribes and civilizations.

The thing is, the search for “biblical accuracy” is so narrowly focused among the scholarly world—so hyper-specific—that often researchers simply “cannot see the forest for the trees.” Context is all-too-often ignored or undervalued. Evidence for the biblical account is quite literally all around us—even in today’s somewhat-removed, modern world (here’s a case in point).

Of course, man’s history of effacement doesn’t help—the ancients had a tradition of erasing the names and faces of the conquered. (Actually, not just the ancients; a modern example is the book burnings of Nazi Germany.) There are so many inscriptions that are “nearlys” or “almost certainlys”—inscriptions that describe biblical contexts to a T, yet the money word—the name—is all or partially missing. There are numerous examples of this rather “conveniently” placed damage.

Still, even the generic names provide much evidence for the biblical account—for the Bible having been written in original contexts, just as it describes. The Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology has produced a series on this subject, examining the three divisions of the Hebrew Bible and looking at the extant evidence for their traditional dating and authenticity of writing. You can find them here: The Antiquity of the Scriptures: the Torah; the Prophets; the Writings.