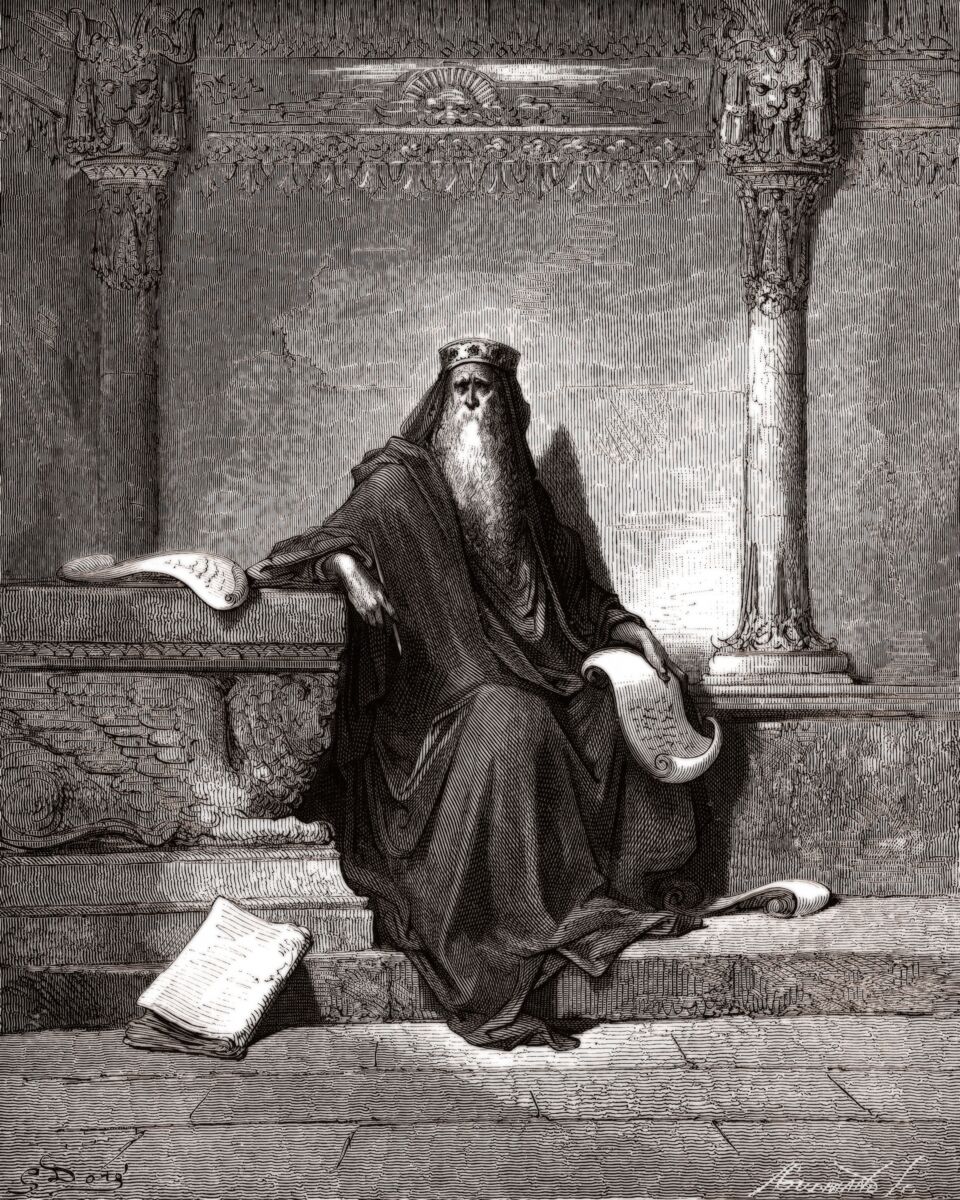

“The song of songs, which is Solomon’s.” So begins the Song of Songs, the Bible’s great poème d’amour. But no one really believes this book was written in the 10th century b.c.e., the time of King Solomon, right?

There’s a reason many scholars and critics reject the 10th-century b.c.e. authorship of this book: It contains several late, post-exilic language elements, including Persian loanwords (e.g. pardes for “orchard”; egoz for “nuts”) and late forms of Hebrew spelling. It uses אני as a personal pronoun, where at least some usage of the early form אנכי might be expected; the longer דויד for “David” found throughout the late books of Ezra, Nehemiah and Chronicles, where earlier texts almost ubiquitously use the shorter דוד. Still, at least a hint of earlier elements is present (e.g. the shorter spelling of Jerusalem as ירושלם, rather than the longer ירושלים).

The use of linguistic elements from both late and early periods has led a few scholars to believe the book was written earlier and then later edited. In Dating the Old Testament, the very conservative Craig Davis suggests that “Song of Solomon was probably originally written at the time of Solomon,” but that the “language of the book was thoroughly revised in the post-exilic period, around 400 b.c.e., to reflect the spoken vernacular Hebrew of the time.”

From a Bible-literalist standpoint, this is hardly problematic—the Bible itself reveals such a practice. Proverbs 25:1, for example, announces that the continuing texts of the book “also are proverbs of Solomon,” but those “which the men of Hezekiah king of Judah copied out.” In similar manner, the Talmud contains recognition of the Song of Songs as a later-compiled text—attributing it to “Hezekiah and his colleagues” (Bava Batra 15a). Yet as noted above, given some of its linguistic elements, even this attribution is likely centuries too early. Nevertheless, from a strictly biblical standpoint, the point is made that such an early preexisting composition could have conceivably been reassembled during a later period (such as during the time of Hezekiah or Ezra), “reflect[ing] the spoken vernacular Hebrew of the time.”

Still, for many, the notion of the Song of Songs in its original form going back to King Solomon almost 3,000 years ago remains difficult to swallow. And it doesn’t help matters that the text does not identify period-specific, geopolitical events. It is, after all, a comparatively more abstract love song, not a detailed record of wars or international relations. Again, in the assessment of Davis, “Song of Solomon stands largely alone in the Old Testament, with no major dependencies on other books and without lending information to other books,” and with “verbal ties [that] do not seem long enough or numerous enough to draw major conclusions” (ibid).

For many, the genesis of this text in the 10th century b.c.e. can be based only on faith, with the lack of any appreciable outside, corroborative evidence for the setting or authorship.

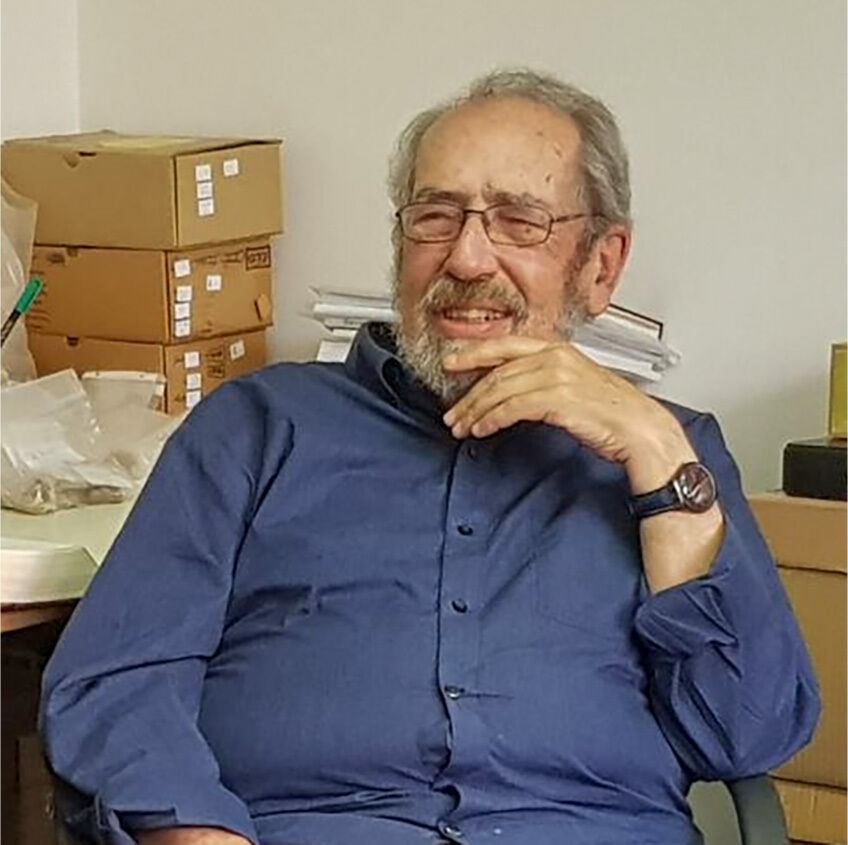

Archaeologist Prof. Gabriel Barkay, Israel’s 81-year-old living legend—a man affectionately referred to by some as the “dean of biblical archaeology”—begs to differ, making his case in an extraordinary book released last year.

‘For Your Eyes Only’

Professor Barkay is one of Israel’s most esteemed archaeologists. He has practiced archaeology in Israel for more than 50 years and is cherished as one of the last of the “old guard.” Born in Hungary in the Budapest Ghetto during the height of World War ii and the Holocaust, Barkay immigrated to Israel in 1950. He studied archaeology, geography and comparative religion, graduating from Hebrew University and later Tel Aviv University with a Ph.D. Among the many highlights of his storied career, he is most famous for the 1979 discovery of the 2,600-year-old Ketef Hinnom Scrolls—the earliest biblical text ever discovered. Also notable is his role as cofounder and codirector of the Temple Mount Sifting Project, alongside Zachi Dvira.

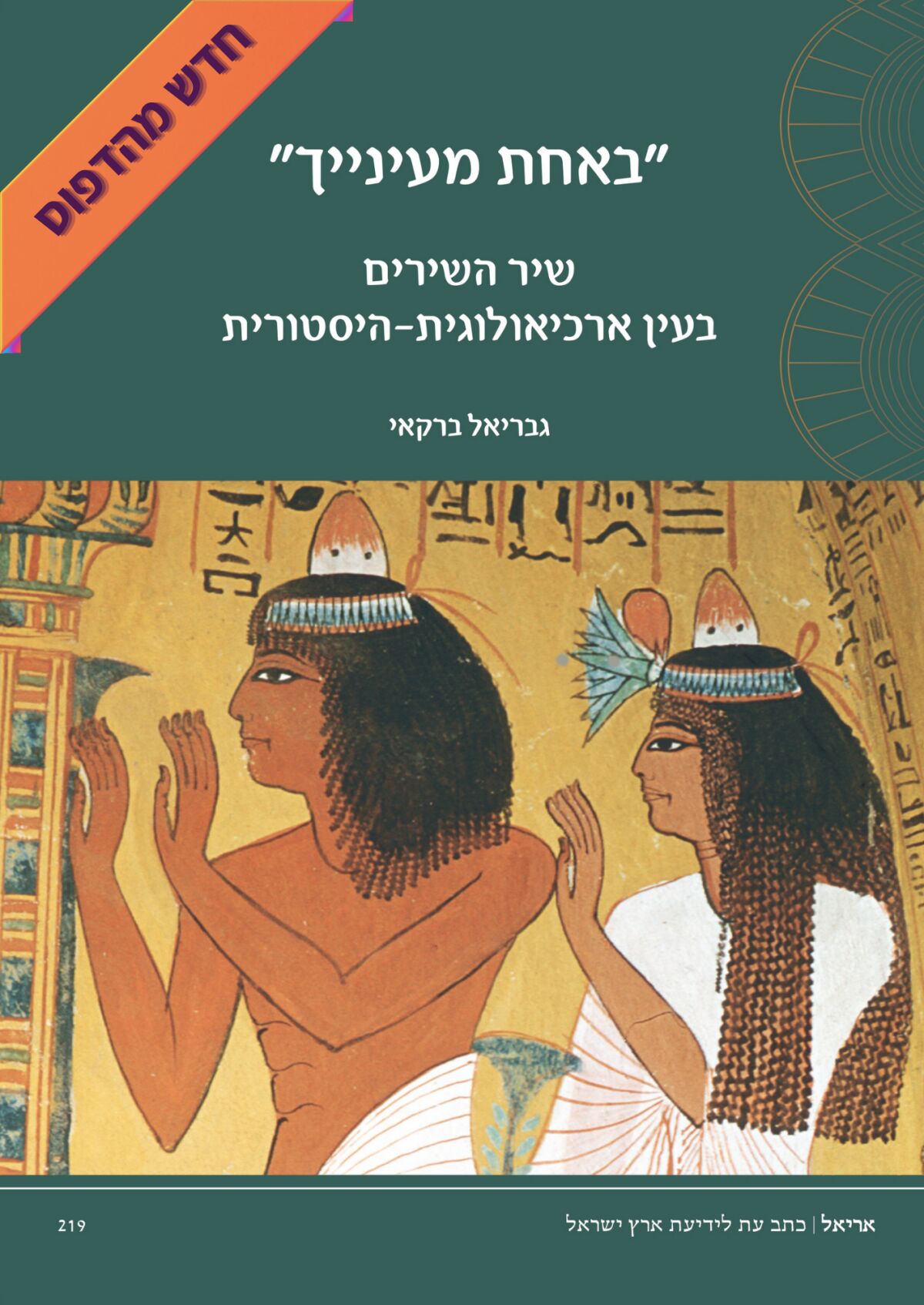

Last year, Barkay—despite a difficult struggle with deteriorating health—published a brand-new book on the subject of the Song of Songs in its early historical context: ‘For Your Eyes Only’: Song of Songs Through Archaeological-Historical Eyes. It is a remarkable book that has largely flown under the radar—undoubtedly due to it being available only in Hebrew. An English version is in the works. (The quotes to follow are our own translation and are likely to differ slightly from the final English text. Note also that the above-mentioned title is provided in English within the Hebrew text; it differs slightly in translation from the Hebrew original.) In assembling the book, Barkay was aided by his research assistant Amichay Lifshits (who served as my own assistant during our Ophel 2024 excavations). The Hebrew-language text, produced by Ariel Publishing, is available for purchase from the Israeli Institute of Archaeology website.

At its core, Barkay’s book rejects the common premise that the Song of Songs is total abstract allegory (with no serious historical underpinning) and instead sees it as grounded in historical realities that anchor the time and place of its original composition. “Throughout its history of research, the Song of Songs has not been attributed historical importance,” Barkay writes. “[T]his work renders it a historical source …. Our goal is to reveal the tangible in the love poetry. That is, the world of material culture that stands behind the text of the Song of Songs. … Our basic assumption is that the material culture reflected in the text allows us to determine the time of its writing.”

“Many generations of commentators have hardly dealt with the realities behind the chapters of the Song of Songs. Most of them have dealt with the literary, theological and linguistic aspects of the text,” Barkay observes. Yet “[t]here is no doubt that the text reflects a historical reality,” a “clear tangible background … in the pre-classical world of the First Temple Period. Archaeological analysis of material cultural items mentioned in the text brings us closer to this period and allows us to establish the background for the love song in the early Iron Age ii.”

In progressive order, Barkay expounds on numerous different features of the text—linguistic, geographical, horticultural, architectural, etc (each presented in a dozen separate chapters)—and explains how the foundation of the book is rooted firmly within the Iron Age ii period generally, and the Iron Age iia specifically (the time in which Solomon lived). What follows are some highlights from Professor Barkay’s book. (Note that our default Bible translation is the Jewish Publication Society, which follows the Masoretic divisional system, also used in Barkay’s book. Several verses of Song of Songs are numbered differently in other translations, which follow the more common Geneva numbering system. Where there are differences, corresponding verse numbers are indicated.)

Linguistic Features

Song of Songs has long been recognized for its unusual quantity of hapax legomena—words that appear only once in the Hebrew Bible. These words can prove a real challenge to later readers and translators, with their rare use and lack of comparative context often resulting in their original meaning becoming forgotten over time. There are some 30 to 50 such words in Song of Songs (the exact number differing based on how they are counted and categorized). Given the comparatively short length of the text, this puts it statistically in second place for percentage of such words in the Hebrew Bible, after the linguistically confounding book of Job (see Prof. Frederick Greenspahn’s “The Number and Distribution of Hapax Legomena in Biblical Hebrew”).

Yet over the last century of archaeological discovery, certain of these unusual words in Song of Songs have been paralleled and illuminated by a number of Iron Age inscriptions, including those going back to the 10th century b.c.e. In his book, Barkay highlights these and other interesting linguistic parallels—“words and concepts from the text of the Song of Songs that appear in Hebrew and Phoenician inscriptions from the Iron Age.” Here are a few:

- שחרחר (Song of Songs 1:6)—this hapax legomenon, typically rendered as “black,” is paralleled by two extant (albeit unprovenanced) seals featuring this as a personal name.

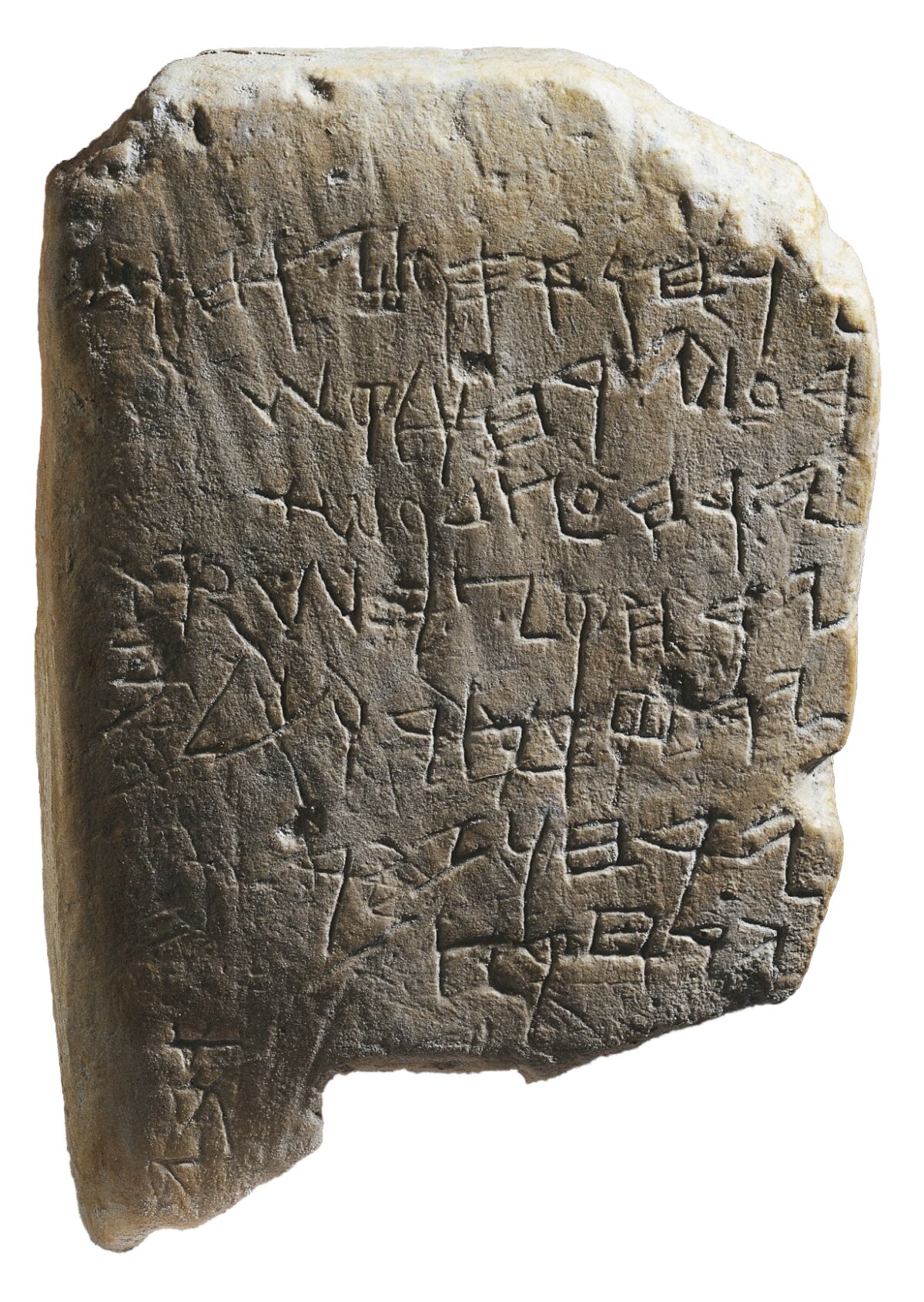

- זמיר (Song of Songs 2:12)—this hapax legomenon, typically assumed to refer to a time when birds sing (based on the context of the verse), appears on the 10th century b.c.e. Gezer Calendar, where it refers specifically to a two-month agricultural period of pruning.

- סמדר (Song of Songs 2:13, 15; 7:13; verse 12 in other translations)—this term is found three times in the Bible—all only in Song of Songs—and is generally understood to relate to grapes. The term is found on an eighth-century b.c.e. vessel inscription from Hazor.

- תרשיש (Song of Songs 5:14)—this term is used to refer to a precious stone and also a related place-name (whose location has long been debated); it appears on a ninth-century b.c.e. Phoenician stone inscription from Sardinia.

- אגן (Song of Songs 7:3; verse 2 in other translations)—this rare word refers to a specific type of wine basin and is paralleled on a seventh-century b.c.e. Arad ostracon.

“These ancient inscriptions indicate that the world of the Song of Songs is connected to the culture of the First Temple Period,” concludes Barkay.

Geographical Features

Things get even more interesting with the geographical information. In this, Barkay is, in a sense, breaking new ground—he notes the surprising lack of research on Song of Songs from a geographical perspective. “Traditional and modern commentators have not dealt at all with the historical geography of the Song of Songs” on the premise that for an allegorical love song, the “geographical-historical aspects of the text have no significance.”

“Most of those who have studied the history of the land of Israel and the interpretation of the Song of Songs have never thought twice about learning history or historical geography from the Song of Songs,” he writes.

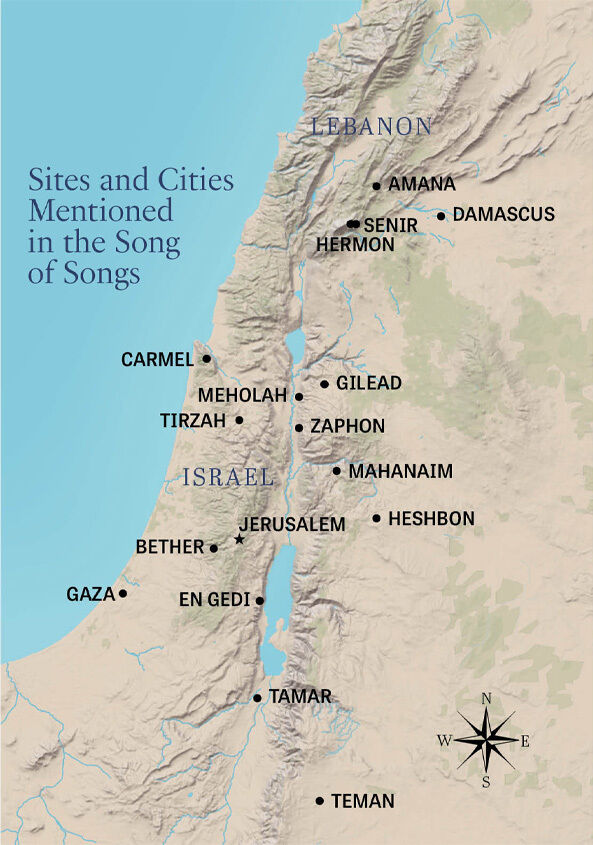

Barkay enumerates 20 cities and places mentioned in the text—most of which are known with “reasonable certainty” and “in light of biblical sources and archaeological data, there is evidence for the existence of these sites during this [Solomonic] period.” Remarkably, “[a]mong the cities mentioned in the Song of Songs, there is not a single one that is known to have been inhabited solely in the later stages of the monarchical period or during the Second Temple Period. There is not a single place-name of Greek origin, as we would expect to find if the text was indeed composed in the Hellenistic or Roman periods. Therefore, none of the place-names mentioned in the Song of Songs indicate anachronism, or that the text was composed after the monarchical period.”

Almost as remarkable as the mention of certain Solomonic locations is the lack of mention of certain others. In describing in eyewitness-detail the beauty of certain minor Solomonic districts (comparing them to the lover in the text), it omits some of the most powerful and notable cities belonging to the king—cities like Gezer, Hazor, Megiddo and others. The very opposite would be expected in the case of a much later author, composing a narrative with the intent of drawing more obvious links to Solomon for his readers, in sourcing material from the books of Kings and Chronicles. Barkay emphasizes that the geographical information in Song of Songs points to an independence from these other, later biblical sources in the composition of the text.

Of additional note is the use of double meaning throughout Song of Songs, especially in relation to geographical terms. Certain locations are invoked, both in the meaning of the Hebrew word generally and a corresponding location of the same name.

Barkay highlights these geographical features in the order they appear in the text. Here are a few highlights:

- Turak (Song of Songs 1:3)—a hapax legomenon that seems to function as a place-name. If so, this is the only such mention, and its location has become lost over time.

- Tamar (Song of Songs 7:7-8; verses 8-9 in other translations)—apparent use of double meaning, referring to both Tamar as a place-name and reference to dates. This was a location built by Solomon (1 Kings 9:18—note that there is some debate about the place-name in this verse; Barkay prefers the link with Tamar based on the Masoretic Text).

- Hills of Bether (Song of Songs 2:17)—identified with the Iron Age ii settlement of Tel Betar, west of Bethlehem, in the Judean mountains.

- Mount Gilead (Song of Songs 4:1)—mentioned twice in Solomon’s list of regional districts (1 Kings 4:13, 19)—this territory gradually became lost to the Israelites from the ninth century b.c.e. onward.

- Amana, Hermon, Senir (Song of Songs 4:8)—three mountain ridges overlooking Lebanon. The mention of these ridges reflects an intriguing level of detail about the landscape of the far north—mountainous territory to which the Bible describes Solomon sending workmen (1 Kings 5:27-29; verses 13-15 in other translations).

- Zaphon, Teman (Song of Songs 4:16)—probable examples of double meaning, referring to “north” and “south” respectively, but also fitting with locations of the same names. The former is located in the Succoth Valley, mentioned as having been conquered by Sheshonq i (Shishak) in the 10th-century b.c.e. Karnak Inscription; the latter is a synonym for Edom, likewise under the control of the united monarchy (2 Samuel 8:14) with references to this name including an early eighth-century b.c.e. vessel inscription from Kuntillet Ajrud.

- Tirzah (Song of Songs 6:4)—mention of this location is notable, given its position as the capital within the early years of the breakaway northern kingdom of Israel, from the late 10th century b.c.e. onward (before being supplanted by Samaria). This was likely as a function of Tirzah’s already notable position in the kingdom. Still, this location is not mentioned in Song of Songs for any administrative function, but rather simply for its beauty. This city is likewise mentioned in Sheshonq i’s 10th-century b.c.e. Karnak Inscription.

- Meholah, Mahanaim (Song of Songs 7:1; 6:13 in other translations)—another probable example of double meaning. The former likely refers to Abel Meholah, one of Solomon’s settlements (1 Kings 4:12), located in the Jordan Valley south of Beit Shean (possibly Tell Abu Sus); the latter generally identified with Tell edh-Dhahab, which served as a regional capital during the days of Solomon (verse 14) and is likewise mentioned by Sheshonq i in the 10th century b.c.e. Notably, this city—mentioned multiple times during the period of the united monarchy—appears to fall out of importance rather suddenly, with no further reference to it following the reign of Solomon. In Barkay’s opinion, the metaphorical reference of these two sites in the context of the “dancing Shulammite” is “one of the most beautiful examples of the author’s linguistic literary style.”

- Damascus (Song of Songs 7:5; verse 4 in other translations)—this important Syrian city was won by David (2 Samuel 8:6); however, it was lost during the latter part of Solomon’s reign (1 Kings 11:24).

- Gaza (Song of Songs 8:6)—another likely example of wordplay, in which “strong as death” (עזה, italicized—the same territorial name) aptly reflects this hostile enemy Philistine territory.

Two particular locations in Song of Songs are mentioned frequently: Jerusalem and Lebanon. Both of these, of course, have special significance to the reign of Solomon—Jerusalem as his capital and Lebanon as the territory of Phoenician King Hiram, with whom David and Solomon shared an unusually close relationship (e.g. 1 Kings 5; 2 Chronicles 2). The Lebanon connection is further reflected in one of Solomon’s key administrative buildings in Jerusalem: the House of the Forest of Lebanon (e.g. 1 Kings 7, 10). Note also 1 Kings 9:19 and 2 Chronicles 8:6, in which these two entities—Jerusalem and Lebanon—are singled out together as the key locations of Solomon’s focus.

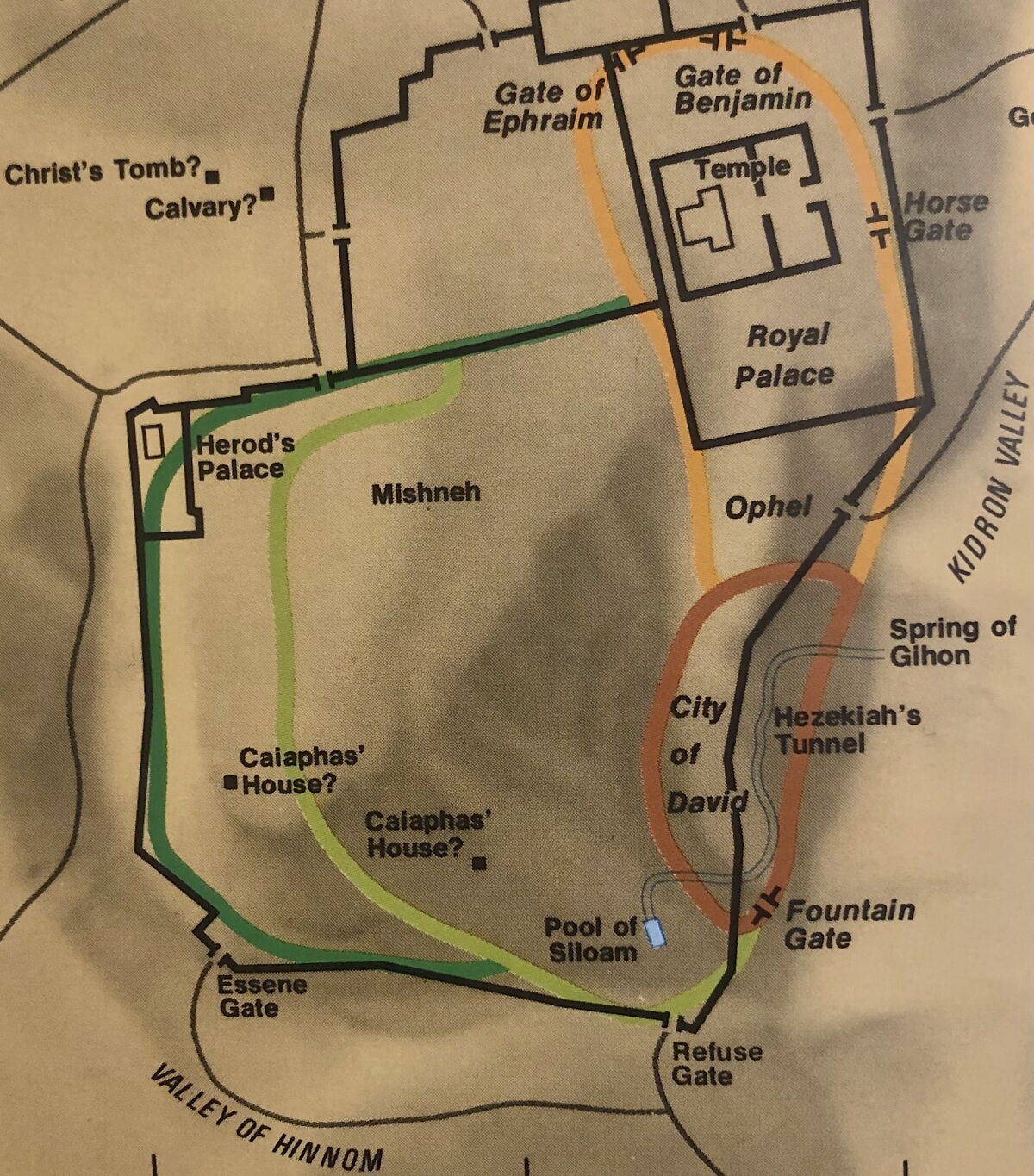

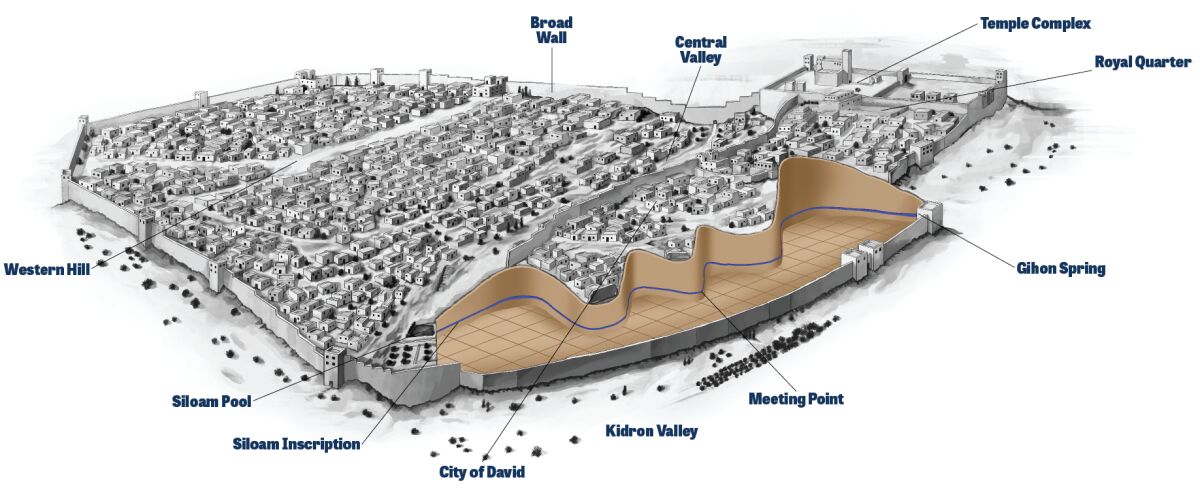

Barkay treats Jerusalem, the most-referenced location, in its own separate chapter. What is perhaps most interesting is what is not said about the city. Nowhere is it emphasized for its size—something that is highlighted by later texts (e.g. Jeremiah 22:8, “this great city”; Lamentations 1:1, “great among the nations”). This makes logical sense when comparing the layout of the city during the Iron iia period with the later Iron iib city—the latter having expanded up to nearly triple the size of the original, with the late ninth-to-eighth-century b.c.e. expansion and bustling metropolis around the Western Hill. The original city plan was comparatively small, occupying only the southern City of David and northern Ophel/Temple Mount ridges.

Based on the description of Jerusalem in Song of Songs, “there is no escape from the conclusion that the city mentioned in the text did not include the areas of the Western Hill. In other words, the text was composed before the significant urban growth of Jerusalem, and the city represented reflects the smaller ancient core,” writes Barkay.

Military Features

Surprisingly, the love song features quite a number of military particulars—though it knows of no war (broadly comparable to the reign of Solomon). These military details “represent the world of the Iron Age ii period, and there is no data that clearly belongs to later periods,” writes Barkay. Here are a couple of examples:

- Pharaonic chariots and horses (Song of Songs 1:9)—Solomon was known for his trade with Egypt in horses and chariots (e.g. 1 Kings 10:28). This interesting positive reference to Egyptian chariotry—infamous elsewhere for its negative, Exodus-related imagery—fits well with the picture of peace and intermarriage between the kingdoms during the time of Solomon. Additionally, the added detail in the following verse, referring to “cheek-circlets” and “neck beads” (verse 10), parallels early depictions of royal Egyptian decorated horse harnesses and bridles.

- Shields hung atop towers (Song of Songs 4:4)—this practice of hanging shields along the top of fortifications, also recorded elsewhere in the Bible, is aptly demonstrated in the circa 700 b.c.e. reliefs of Assyrian King Sennacherib, depicting the fortifications of Lachish as lined with circular shields.

Additional Features

The list of details goes on. The following are additional teasers:

- Horticulture: The word שושן, generally translated as “lily,” is found more often in Song of Songs than anywhere else in the Bible (eight out of 15 times). It more likely refers to the lotus flower—something “prevalent in Egyptian, Phoenician and Assyrian artistic depictions, and especially in Iron Age ivory art.”

- Jewelry: “Set me as a seal upon thy heart” (Song of Songs 8:6)—this imagery is reflective of the typical royal and administrative seal stamps, which would often be worn around the neck, thus lying effectively “on the heart.” “Seals have been used from prehistoric times to the present day, but they are most characteristic of the culture of the royal period in Israel and Judah, from the 10th century b.c.e. to the destruction of the first temple,” Barkay notes. Hundreds of seals and seal impressions have been found in Jerusalem, a significant percentage of which date to or around the 10th century b.c.e. (see “A Corpus of Iron Age ii Inscriptions From Jerusalem: The Background for the Writing of Biblical Texts,” 2024, by the present author and Prof. Yosef Garfinkel).

- Currency: Song of Songs 8:11-12 describe payment in “pieces of silver,” the system of transaction during the Iron Age (and earlier). During later periods, especially beginning in the sixth century b.c.e., this shifted to a system of coinage. “The language mentioning the price and value of agricultural produce is certainly ‘at home’ in the Iron Age,” writes Barkay.

- Apiculture (beekeeping): Song of Songs 4:11 and 5:1 mention the consumption of honey and honeycomb. “Until recently, it was claimed that honey was known in the land of Israel during the biblical period only from beehives that happened to be encountered along the travels of people at that time,” writes Barkay. This changed following the excavations of Prof. Amihai Mazar at Tel Rehov, in which “an industrial beehive was discovered where honey was produced,” dating “to the Iron Age iia (10th–ninth century b.c.e.).” Further, analysis of the remains revealed that these hives contained a very select species of bee imported from Anatolia—a species that is “less aggressive, and produces a greater amount of honey than native bees,” Barkay notes.

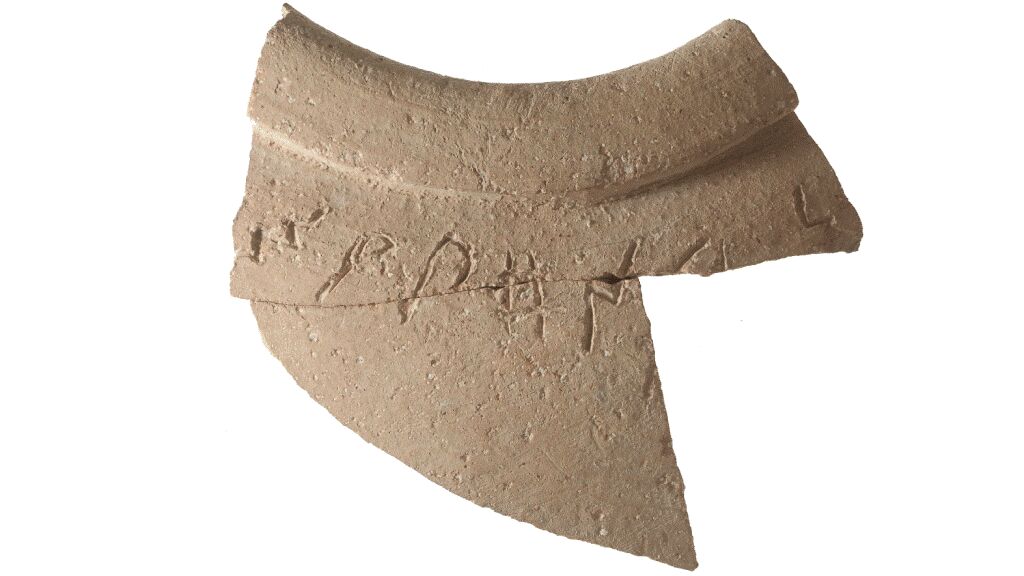

- Spices: There are numerous references to spices and perfumes in Song of Songs—Barkay enumerates about 10 different types—most of them originating in distant locations, requiring facilitation by long-distance trade (something befitting the biblical descriptions of Solomon’s navy). Barkay draws special attention also to the visit of the Queen of Sheba, with an apparent nod to her visit in Song of Songs 3:6: “Who is this that cometh up out of the wilderness, Like pillars of smoke, Perfumed with myrrh and frankincense, With all powders of the merchant?” This imagery brings to mind the arrival of the Queen of Sheba and her retinue from the southern desert trading routes. 1 Kings 10:10 notes that “there came no more such abundance of spices as these which the queen of Sheba gave to king Solomon.” Barkay highlights the 2012 discovery of the Ophel Pithos Inscription by Dr. Eilat Mazar, dating to the 10th century b.c.e., and Dr. Daniel Vainstub’s 2023 analysis identifying its script as Ancient South Arabian (from the territory of Sheba), with reference to a well-known Sabean “spice” commodity named on the vessel as ladan (ladanum; see Vainstub, “Incense From Sheba for the Jerusalem Temple”).

Dating

Barkay concludes his 160-page publication with a discussion on dating the text as a whole, reassessing key points that ground the text in the Iron Age generally and the 10th century b.c.e. specifically. “[T]he conclusion to which the discussion leads is that the Song of Songs originated in the days of Solomon, somewhere in the 10th century b.c.e.” Points highlighted by Barkay as summary evidence to this end include:

- A sub-layer of Canaanite culture—e.g. reference to Baal Hamon (Song of Songs 8:11); possible allusion to a Canaanite site atop Mount Carmel (Song of Songs 7:6; verse 5 in other translations); word pairings familiar from late second-millennium b.c.e. Canaanite-Ugaritic literature.

- The love-poetry genre—something common in the ancient Near East, with parallels in Mesopotamian and Egyptian literature. Knowledge of such literature gradually became lost during the later classical periods.

- Literary dependence—Isaiah and Jeremiah contain select passages “undoubtedly influenced by the Song of Songs,” thus the text predates their own.

- Textual unity—a picture that fits only with the time of the united monarchy. “Song of Songs does not mention places, figures, or other details that are later than the days of the united kingdom.”

“The main, and perhaps the only, argument for the late dating of the text is linguistic,” concludes Barkay. Yet “[w]hen this argument is placed against the other considerations mentioned in this text, it seems to have little relative weight.”

Such late, piecemeal linguistic features are hardly problematic in Barkay’s view. “[I]t is certainly possible that late syntactic formations, Aramaisms (influences of the Aramaic language on the text) and late foreign words penetrated the text before the final version was formed.” Still, “[t]he text does not contain any late geographical name or distinct word in Greek that would help date the text to the times of the second temple. … Likewise, the text does not mention material cultural data characteristic of the late Iron Age. The descriptions in the Song of Songs do not include any anachronism that might betray the hand of a late author”—instead, perhaps merely the hand of an editor or redactor, perhaps of the likes of Ezra on the scene during the Persian period.

“We have no doubt that even if the Song of Songs contains later linguistic features, it has an ancient and solid foundation that allows it to be dated to the days of Solomon,” Barkay concludes.

The Song of Songs, Which Is Gabriel’s

This new book from Gabriel Barkay is more than just another publication. In a real sense, it’s a swan song of his own career, looking back across his more than half-century in the field of biblical archaeology. It’s a field that has witnessed many changes—not all of them for the better. “Since the 1970s, biblical studies on the one hand and archaeology on the other have drifted apart to the point of an almost complete disconnect,” Barkay laments.

The disconnect is so stark that many have questioned the very name ‘biblical archaeology,’ or the very existence of such a discipline. There were others who disdained this field and saw it as a fundamentalist pursuit …. There is a tendency among scholars of biblical language, literature and history to treat material culture with contempt or to ignore it …. The Song of Songs is a book in which material culture occupies an extremely important place.

Professor Barkay’s book is an attempt to rectify the situation, not only in relation to analysis of the Song of Songs but toward the field of biblical archaeology as a whole. “The purpose of the discussion here is also to restore the lost respect for the connection between the biblical text and material culture,” he writes. “This connection was largely lost after the death of William Foxwell Albright and the decline in the importance of the school he founded—something which resulted in the premature death of biblical archaeology. Some of the reasons for the disconnect are related to modern political circumstances and the formation of extreme minimalist postmodern schools that deny any ancient background to the books of the Bible, including the Song of Songs.” Yet biblical studies and archaeology are not mutually exclusive, he argues. “The realia explain the text, and sometimes the text explains the material remains, and the two disciplines complement each other.”

In Professor Barkay’s book, then, we have a resource that—as appropriately summarized by the publisher—“reveals the world of material culture described in the biblical text, and for the first time, gives the Song of Songs its rightful place as a valuable historical source.”