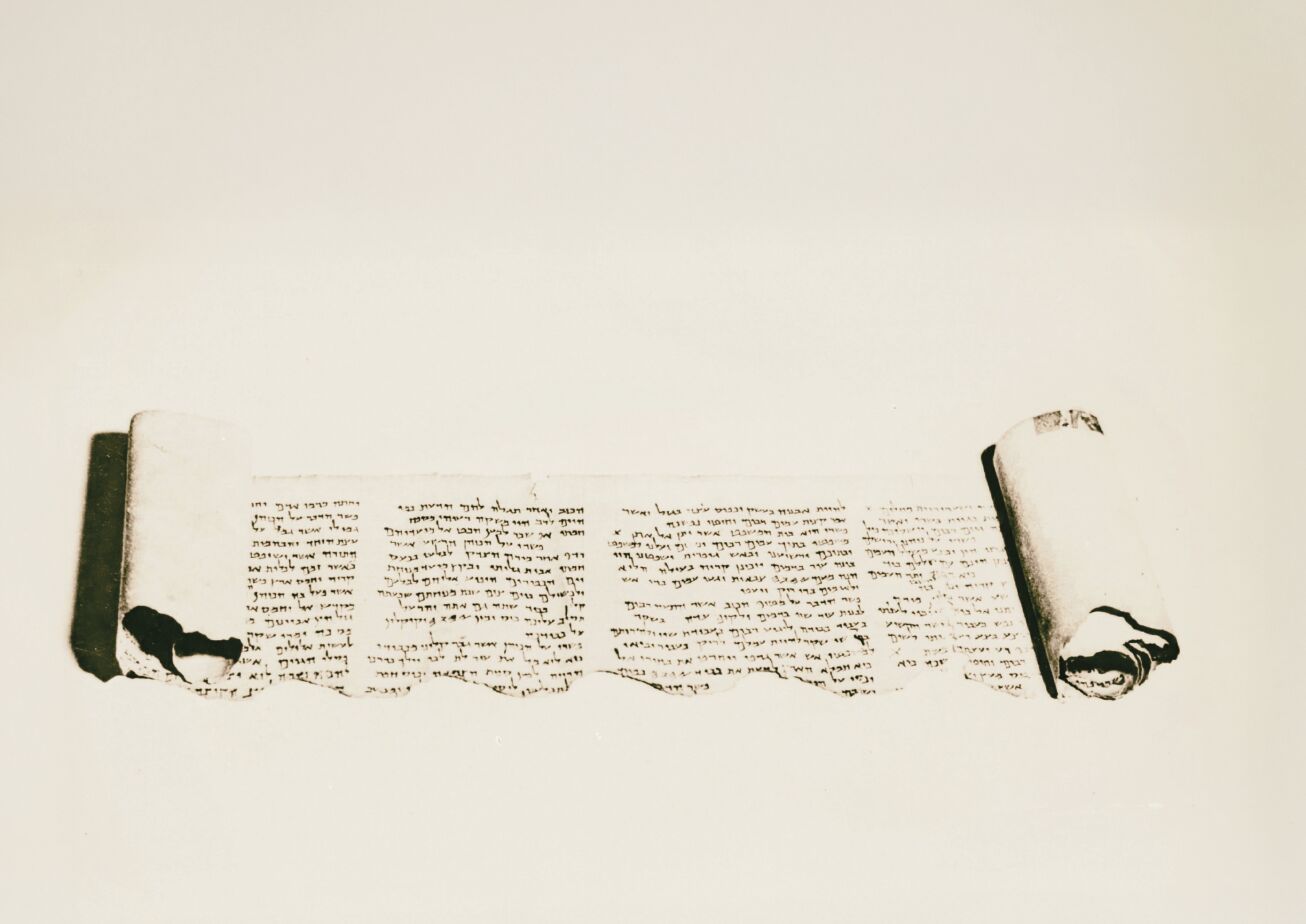

No matter one’s opinion of the Bible, it is astounding how the biblical text has been preserved for so many years. First, in how its various texts were written, maintained and compiled over centuries before reaching the form we know today. And second, how that final form has not changed thousands of years later. Archaeological finds show that the “Masoretic Text” of Hebrew canon from just over a millennium ago (upon which most translations are based) is essentially identical to the most archaic scrolls found tucked away in ancient caves and walls.

How awe-inspiring, to say the least!

The traditions necessary to preserve such records so accurately are quite bewildering. But consider how the original texts survived past their initial composition—how copies were made and preserved in the ancient world. Beyond the ordinary decay of time, how did manuscripts survive cataclysmic world events, traversing national borders, enemy incursions and captivities?

What archaeological treasure troves like Qumran and Masada suggest is, not only do these texts survive, but they do so down to some of the most minute scribal details like line breaks and the sizes of certain characters next to others.

But how much can we learn about the preservation of the Bible from the Bible itself? Does it address how official historical documentation could survive events like the Flood or the destruction of Jerusalem? How do details documented by Jeremiah in Egypt end up in the same volume as those recorded by a Persian-based eyewitness in the days of Esther?

Many of these answers are divulged in the Bible. It also helps to have a basic understanding of how written texts were handled in a world far removed from our modern digital age.

It is worth noting that the early Christian era exalted Jewish scribal practices. Paul, the famous Pharisee-turned-Christian, acknowledged Jews as the authority on preserving the “oracles of God,” which included the sacred Hebrew writings (Romans 3:1-2).

In Jesus’s day, when the Hebrew Bible was in its final form and available in the average synagogue (Luke 4:16-21), Jesus himself acknowledged that the scribes had the scribal authority of Moses (Matthew 23:2). He endorsed the contents of the Hebrew Bible, not just conceptually, but in how they were recorded—that not even the smallest letter or smallest scribal mark would pass away (Matthew 5:18).

A Floating Library

The first time the word “book” is found in the Bible is in Genesis 5:1: “This is the book of the generations of Adam ….” The Bible often cites other texts as sources (see “The Bible ‘Is Not History’—Because It Doesn’t Cite Sources?” for more information). In this example, Moses addresses how this information reached him: It was written in a book naming the direct line from the first man to Noah.

Based on the ages given in the following Masoretic verses, the life of Noah’s father, Lamech, overlapped Adam’s by over five decades. Since this incredible information is explicitly mentioned as being in written form—and Moses obviously was not an eyewitness or contemporary to any of this history—it must have been preserved through Noah’s ark and eventually replicated.

Nearly two millenniums after the Flood, Ezra presents a detailed genealogy tracing back to the first man (1 Chronicles 1-8). This compilation is rooted in other genealogies given in various books of the Bible (e.g. 1 Chronicles 5:17) and another book of genealogies given later in the volume (2 Chronicles 12:15). At this point in Judah’s history, officials were relying a great deal on these documents to structure the priesthood properly after the return from Babylonian captivity (Ezra 2:62; 8:3; Nehemiah 7:5, 64).

For many today, it’s a challenge to trace family heritage back beyond three or four generations. Yet thanks to scribal records, biblical genealogies go back to pre-Flood destruction.

The Bible narrative accounts for a chain of custody of written records from the pre-Flood to the post-Flood world. Whoever the specific scribes were, the narrative assigns Noah as custodian of these documents and the ark as a floating library of sorts.

What’s more, the Bible says Noah lived another three and a half centuries after the Flood, even through the infamous tower of Babel incident—whose record bears another important genealogical insertion (Genesis 10).

The duties of either recording the history or preserving its documents would have presumably passed to his son Shem and the line of men who were ancestors to Abraham and whose genealogy is clearly recorded in Genesis 11 (verses 10-32).

Traveling Heirlooms

The post-Flood genealogies imply that a careful record of documentation was kept throughout the centuries. The chain of custody of these historical documents can be determined using only the biblical record through the time of Abraham’s wanderings.

Genesis 12 through 25 record great details of this patriarch’s life, including impressively specific geographic markers and contemporary regional rulers. Some of the account includes details even an eyewitness wouldn’t know (e.g. Abraham’s and Sarah’s dreams). Though these are less verifiable than a genealogy, it could indicate Abraham or Sarah penned autobiographical information for future writers. The same goes for Lot’s account, which beyond Sodom’s destruction, divulges some uncomfortably explicit genealogical details about him and his daughters.

When Sarah died, Abraham bought a cave in what eventually became Hebron. The land’s owners wanted to gift it to him, but he insisted on purchasing it for its appraised value. The account in Genesis 23:16-18 reads very much like a land deed: giving the sale price and certain geographic markers. This exact spot factors into several generations of biblical characters over many decades.

Enduring Egypt

Not being an eyewitness to any of these objective details contained in Genesis, its author, Moses, must have received reliable documentation somehow (for more information, read “The ‘Genesis Tablets’: An Introduction to the Wiseman Hypothesis!”). Though skeptics could argue that some of these details could have been conjecture (and while its supporters could claim they were simply the result of divine revelation) an impressive amount of detail could easily have been fact-checked and verified through the centuries that these texts existed. The Genesis 5 genealogy clearly is from a “book,” and not an oral tradition. This, along with other historical documents, somehow found its way into Moses’s hands.

But how? Moses grew up at the height of Israelite slavery in the land of Egypt. How could he or any of his contemporaries get their hands on these kinds of historical documents?

While both Abraham and Isaac briefly ventured into Egypt, their descendant Joseph spent a great deal of time there (Genesis 39-50). Due to an unprecedented famine, Joseph’s father, Jacob (renamed Israel), had to uproot his entire settlement from the land that would become Israel and move to Egypt—where Joseph’s economic policies had created a sustainable environment.

“And Israel took his journey with all that he had, and came to Beer-sheba …” (Genesis 46:1). Verse 5 says Pharaoh’s wagons took them the rest of the way: “And they took their cattle, and their goods, which they had gotten in the land of Canaan …” (verse 6).

The following verses read very much like a census record, detailing names and exact numbers. Think of the property being transferred to Egypt and, among it, the family library!

The record says Joseph lived long enough to see three generations beyond his son Ephraim (Genesis 50:23). Interestingly he told his family that God would “bring you up out of this land unto the land which He swore to Abraham …. [A]nd ye shall carry up my bones from hence” (verses 24-25). He knew his family was destined to leave Egypt eventually—at which time his bones would return to the land where he was born. Until then, he was “put in a coffin in Egypt” (verse 26). Some Egyptian tombs were known to preserve copies of text. Though Joseph would not have subscribed to the same mystical reasoning to do so, perhaps some texts were preserved in his burial chamber while others were preserved among households in Goshen.

For all of Israel’s sufferings in Egypt after Joseph’s death, their family lineage was well known and documented (see Exodus 6:14-25).

The removal of Joseph’s bones is recorded in Exodus 13:19. The exodus, though “urgent,” was not some mindless, panic-driven departure. As the voice from the burning bush foretold of this exodus: “ye shall not go empty” (Exodus 3:21). In addition to all the spoil and plunder from the Egyptians, Moses was able to secure this vital family heirloom—the bones of the great patriarch. Moses must also have secured documents such as the one he cited early in Genesis: “the book of the generations of Adam.”

‘By the Hand of Moses’

The Bible gives no indication exactly when in his life Moses compiled and penned the book of Genesis and the autobiographical details of his time in Egypt, though the creative-writing process itself started at least as early as the shores of the Red Sea, when Moses composed a “national anthem” of sorts in praise of the great miracles Israel experienced there (Exodus 15:1).

In Exodus 16, we read of a jar of manna to be “kept throughout your generations” (verse 33), laid up “before the Testimony, to be kept” (verse 34). This was before the “ark of the testimony” was built and even before the Ten Commandments were written into stone. So this culinary artifact was kept next to some sort of legal document!

Then comes an explicit mention of a written record in Exodus 17. After Israel’s victory against the Amalekites, God instructed Moses: “Write this for a memorial in the book, and rehearse it in the ears of Joshua: for I will utterly blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven” (verse 14). Many translations render the document as “a book,” but the Jewish Publication Society Tanakh correctly renders the Hebrew: “in the book.” For God to mention “the book” to Moses, both parties in the discussion knew which book was being referenced! Moses was already in the process of penning an official record.

This victory was recorded to rehearse with Joshua. The rest of the verse explains this greater significance—not just noting a miraculous victory but documenting the fate of an enemy nation. This was highly relevant information centuries later in the time of Samuel and King Saul, when this particular detail of this “book” was referenced (1 Samuel 15:2-3), something Saul should have been familiar with had he followed the command to write out his own copy of the books of Moses (Deuteronomy 17:18).

And in case we’re unsure of Moses’s authorship of these records, he is credited as the author in dozens of passages that reference the “commandment of the Lord by the hand of Moses” or information “written in the law of Moses”—from the time just after Moses’s death through the time of Nehemiah and Malachi.

Moses himself records some of the process. Much of this writing took place around Mount Sinai, early in Israel’s wanderings (Exodus 24:4; 34:27). He read from the book to the people (Exodus 24:7; Deuteronomy 28:58, 61; 30:10). He also documented a couple of national censuses during these wilderness years (Numbers 1; 26) and recorded the various paths Israel took through its wanderings (Numbers 33:2). Moses even cited another volume that was not included in the biblical canon (Numbers 21:14)—an eye-opening comment from someone roaming the desert with (as might be assumed) only a few personal belongings.

Also interesting in this context is the epilogue given to Moses’s life in the final verses of Deuteronomy: That “his eye was not dim” (Deuteronomy 34:7) offers a highly useful factoid that speaks to his ability as a scribe—being able to view these tiny marks into the ripe old age of 120.

A Levitical Task

From Moses onward, the chain of custody of Israel’s textual history becomes standardized and not difficult to trace. “And it came to pass, when Moses had made an end of writing the words of this law in a book, until they were finished, that Moses commanded the Levites, that bore the ark of the covenant of the Lord, saying: ‘Take this book of the law, and put it by the side of the ark of the covenant of the Lord your God, that it may be there for a witness against thee’” (Deuteronomy 31:24-26).

Joshua was familiar with its contents (Joshua 1:8; 23:6) and actually had access to these writings (Joshua 8:31-35). These documents would have been kept in the territory of Ephraim, from where Joshua lived and ruled—specifically in the tabernacle at Shiloh where the ark of the covenant was housed for over 3½ centuries. The Levites looked after it as they did all tabernacle items. The priestly line at this time is traceable all the way through the days of the prophet-judge Samuel and the time of kings Saul and David.

The Levite Samuel, who had grown up in Shiloh, demonstrated an intimate knowledge of Israel’s history. He is also credited with writing much of what is known as the Bible’s “former prophets.” As a schoolmaster, his three campuses (1 Samuel 7:16) were renown for raising up some of the greats who would assist in the reign of David. The implication is, by this point in history, he is custodian of the biblical scrolls.

Presumably one of Samuel’s students recorded the information about Samuel’s death and continued to record events leading to David’s ascension to Israel’s throne. This chronicler even referenced another book in Israel’s library when recording David’s elegy over the deaths of Saul and Jonathan (2 Samuel 1:18). Later in the narrative, when David is ruling from Jerusalem, we read that “Jehoshaphat the son of Ahilud was recorder … and Seraiah was scribe” (2 Samuel 8:16-17). The biblical record clearly states who is recording and preserving the history and the library in the days of both David and Solomon; these names are listed among other leaders in the administration (2 Samuel 20:24; 1 Chronicles 18:15-16; 1 Kings 4:3).

This chain of custody becomes even more secure once the temple is built in Jerusalem. Two and a half centuries later, King Hezekiah had access to psalms of David and Asaph (2 Chronicles 29:30; by extension, so did the author of Chronicles two centuries after that). Hezekiah also had access to Solomon’s proverbs (Proverbs 25:1).

The “scribe” continues to be mentioned in conjunction with other leading officials (2 Kings 12:10; 18:18, 37; 22:3; Isaiah 36:3, 22; 37:2). It remains a responsibility of the Levitical families who remained in Judah after the kingdom split (2 Chronicles 34:13). The “scribe” and “recorder” play a part in King Josiah’s epic temple restoration in the mid-seventh century b.c.e. (2 Chronicles 34:8).

This is a key moment, when one of them discovers a famous document in the temple. A priest by the name of Hilkiah “found the book of the Law or the Lord given by Moses … in the house of the Lord” and “delivered the book to Shaphan”—who, in verse 15 is called “the scribe” (2 Chronicles 34:14-15)—and who is apparently more adept at reading the script aloud than the high priest.

This was a bombshell discovery. The king was so shocked by its contents that the entire course of his rule was altered; he realized “our fathers have not kept the word of the Lord, to do according unto all that is written in this book” (verse 21).

Even if these royal scribes had only been preserving more recent history and neglected copying the Torah to this point, here we have preserved an original document that could now serve as a definitive source for future copies. We read that “all the words of the book” were still in existence (verse 30).

His adherence to its instructions achieved a Passover celebration that was unrivaled since the days of Samuel the prophet (2 Chronicles 35:18).

Beyond Babylonian Bedlam

Now we come to a most intriguing part of the plot—how scrolls from just beyond this time made their way into the final canon of Hebrew Scripture. Within a few decades, Judah is besieged by the mighty Babylonian Empire, and its capital city faces cataclysmic destruction.

These events center around Jeremiah, son of the same priest Hilkiah who served King Josiah (Jeremiah 1:1). From what his book records, we learn more about the duties of a scribe—particularly the one serving him, Baruch. The recorded history mentions some tension between Baruch and the other royal scribes (Jeremiah 36). Jeremiah even prophesied the impotence of these scribes’ efforts (Jeremiah 8:8).

Baruch’s job was to put Jeremiah’s words to parchment (Jeremiah 36:4, 17-18—the only verse in the Hebrew Bible to use the word for “ink”). When one of these rolls was destroyed, he and Jeremiah repeated the process (verse 32). Baruch also engaged in public reading of the prophet’s printed message (verses 10-16).

A scribe at this time had specialized skills that would facilitate printing, copying and distributing a written message. He was less of a “ghostwriter” and more like a “publisher” to put it in modern terms. This involved making multiple copies of certain texts. “There seems considerable evidence that the senders of letters … were accustomed to keep copies of letters, even, perhaps letters which might seem to us to be of no great significance,” wrote R. Y. Tyrrell and L. C. Purser in Cicero.

In a world before the printing press, it would have been unusual to write an official document and not create more than one copy—and for the sender not to keep one himself, however much this added to the expense. One copy could be too easily destroyed or lost. In several verses, Ezra mentions multiple copies of letters for transmission through the Persian kingdom (Ezra 4:11, 23; 5:6; 7:11; see also Nehemiah 2:7-9).

This would have been the case for a letter Jeremiah wrote to captives in Babylon, as recorded in Jeremiah 29. This shows that written information from Judah was able to reach Babylon during waves of siege and captivity. Verse 3 names the letter’s couriers, which was important in the ancient world to confirm a letter’s authenticity, especially with a far less formalized postal system. Verses 24-30 even address other contradictory letters that had reached them. All this helps explain how Jeremiah’s writings could survive such a tumultuous time in Judah’s history. The flow of written material did not stop just because Babylon was conquering the Holy Land.

Even Jeremiah’s detailed letter itself told these captives to get comfortable and settle down where they were because it would be 70 years before any returned to the land. Their daily lives, albeit in captivity, would function similarly as though they were back home, including their ability to write and read correspondence.

The later chapters of Jeremiah follow him and Baruch in this post-destruction period, as they are taken to Egypt (Jeremiah 42:7) and then escape back to Judah (Jeremiah 44:14).

Jeremiah 51:59-61 tell us that Baruch’s brother Seraiah had gone into Babylonian captivity a few years before Jerusalem’s destruction and that he brought a copy of Jeremiah’s writings with him. Granted, in this case he was to read it publicly and then toss it in the Euphrates (verses 62-63). But this shows that scrolls could be trafficked into different parts of the region even in this time of siege and captivity.

This account comes just before the final chapter of Jeremiah, which is largely a repeat of 2 Kings 24-25 and which is preceded by this unusual phrase: “Thus far are the words of Jeremiah” (Jeremiah 51:64)

It’s clear this book was undergoing revisions and additions. The version that made it to Babylon years earlier would be different from the final version because the last chapter adds a detail about another wave of captivity that occurred in Nebuchadnezzar’s 23rd year, four years after the destruction of Jerusalem.

The destruction of Egypt that Jeremiah predicted aligns with the overthrow of Pharaoh Hophra in 570 b.c.e.—suggesting Jeremiah stayed in Egypt until Hophra was deposed. His biblical contribution was probably finalized just after his escape back to Judah.

Somehow, a version of this book was preserved for Ezra to include in the final collection. Whether it was something kept in Judah or somehow found its way to Jewish scribes in Babylon, we cannot be certain. Either scenario is not a radical idea. We know that some of Jeremiah’s writings had already made it north to Babylon: Daniel 9:1-2 indicate that the Prophet Daniel, sometime after Nebuchadnezzar, referenced what he’d read in Jeremiah’s book!

The same would be true of the “lamentations” Jeremiah wrote on the death of King Josiah (2 Chronicles 35:25). The compiler of Chronicles had access to this text and would presumably only mention them as “the lamentations” if referring to something else known to be in the same collection. And since the book of Lamentations itself also contains eyewitness accounts of Jerusalem after Nebuchadnezzar toppled it, Jeremiah would have updated this volume with this information before its canonization.

This also helps to explain how other accounts from these years of exile could make it back to Jerusalem for inclusion in the canon—Ezekiel (written along one of the Babylonian rivers—Ezekiel 1:1-3), Daniel and Esther. Our article on Esther’s link to Nehemiah (see “A Nehemiah-Esther Link”) would explain the flow of information between the Persian Empire and the scribes at Jerusalem. Even psalms looking back on the Babylonian captivity were added to the canon (Psalm 137:1).

‘A Ready Scribe’

Within a few decades of Jeremiah disappearing from the scene, the first round of Jews began to return to the Holy Land under the order of King Cyrus of Persia. This was recorded around the mid-fifth century b.c.e. by Ezra.

Ezra 7 describes the exact timing of when he himself returned with a repatriating wave of Jews—several decades after the second temple had been completed. Verses 1-5 establish his heritage from the Aaronite line of priests. Then verse 6 reads: “This Ezra went up from Babylon; and he was a ready scribe in the Law of Moses, which the Lord, the God of Israel, had given ….” Here is another richly revealing verse! Ezra, in Babylonian captivity, was highly skilled, not only at the profession of being a scribe but specifically at being a scribe of the Torah! Verse 10 even describes a deep understanding of what he was transcribing.

He also returned to the Holy Land with a letter from Persian King Artaxerxes—the one presumably linked with the Jewish Persian Queen Esther (Nehemiah 2:6). This king knew of Ezra’s profession and skill set and called him “the scribe of the Law of the God of heaven” (verse 12). Ezra was returning with this document at least, but implicitly many more documents! In verses 19-20, Artaxerxes mentions “vessels that are given thee for the service of the house of thy God,” which would have been mostly gold or silver items, but also “whatsoever more shall be needful for the house of thy God ….”

Ezra specifically requested a few dozen Levites to join this returning crew—“chief men … teachers … ministers for the house of our God” (Ezra 8:16-17). The second temple would now be the center of scribal efforts and the final collection place for works that would endure in the biblical canon. The scribes there would be the custodians of that written legacy for decades to come.

The book of Nehemiah records a key moment when “Ezra the scribe” read the law of Moses on a particular sacred festival (Nehemiah 8:1-2). Other Levites are mentioned as helping people “understand the reading” (verse 8). This particular reading caused a revival of the Sukkot festival (verses 14-15)—a celebration unrivaled since the days of Joshua (verse 17), particularly marked by a daily reading from the biblical scrolls.

The book of Nehemiah exhibits familiarity with the “book of chronicles” Ezra was composing (Nehemiah 12:23); it’s mentioned in this book, which is actually a foreshadowing of Ezra’s volume, since it comes in a book (per the original biblical order) that precedes Chronicles.

A Remarkable Record

“Bind up the testimony,” Isaiah wrote, “seal the instruction among My disciples” (Isaiah 8:16).

The Bible reveals much about how its own words were preserved by the names it discloses in the narrative. Until the time of Moses, the scriptural account reads much like a family history—preserving not only the genealogy but stopping at specific individuals who surely preserved the chain of custody of these documents—Noah, Shem, Abraham, Jacob and Joseph.

From Moses through Ezra, the Bible illuminates a remarkable scribal tradition that preserved the text in a stunningly complete and accurate way.

Thus the scriptural record stands out far above any other text in human history, and it is certainly one that should command the attention of all humanity.