“Jerusalem”—it is arguably the most widely known city name the world over. Yet its full standard form in the Hebrew language, ירושלים, is almost unknown to archaeological discoveries. In fact, out of the over 660 times the city is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, it is only spelled in full five times (typically in the later writings). Most often, the slightly shorter version of the name is used: ירושלם (and even this version was pronounced in a couple of different ways, with differing vowel markings). From the Second Temple Period (530 b.c.e. to c.e. 70), we only have a handful of references to the full form of the city title—namely, from the Dead Sea Scrolls (circa second century b.c.e.), as well as some Maccabean coins.

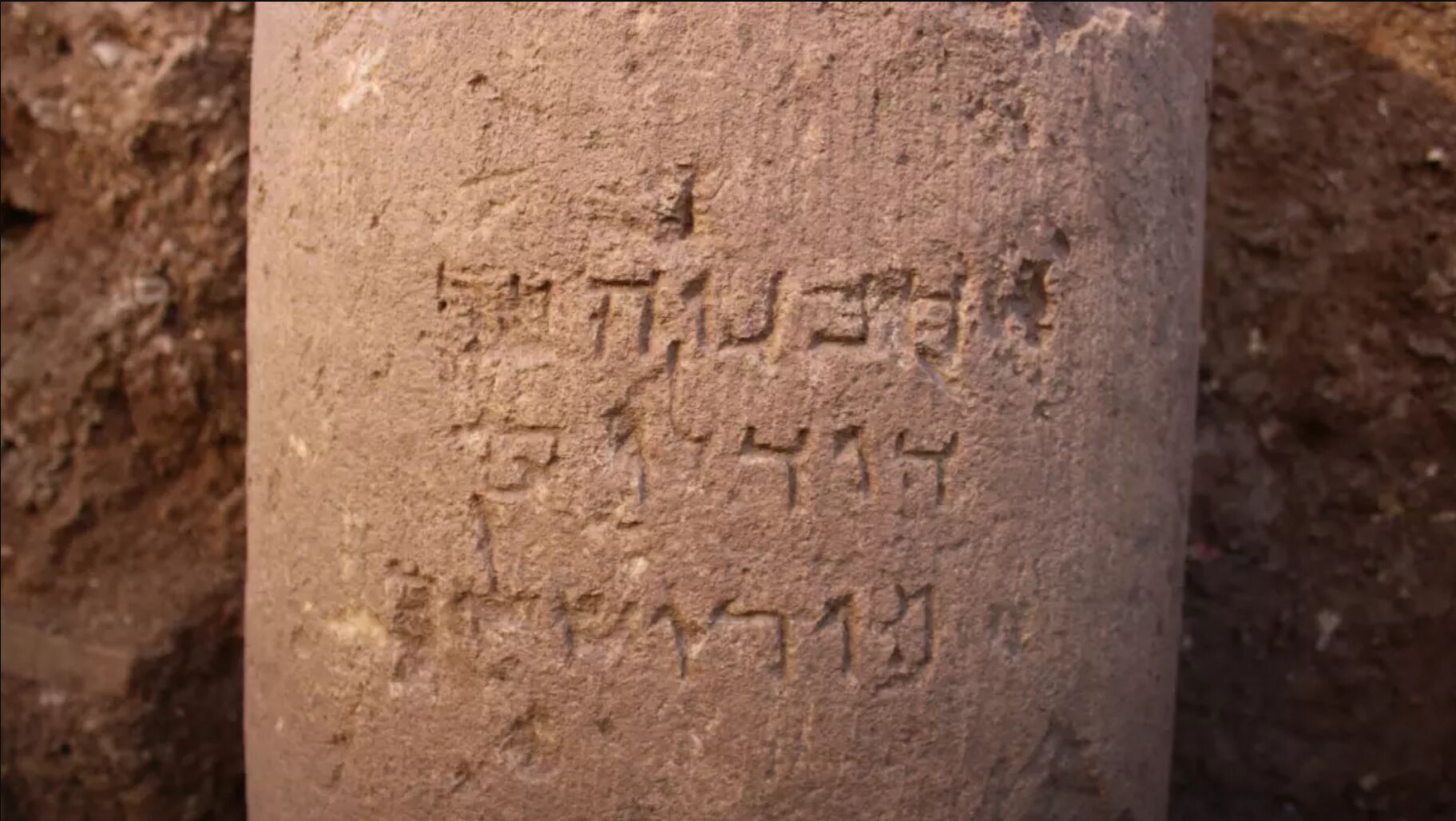

A recent, exciting discovery adds to this small trove of artifacts—the earliest stone inscription bearing the special name in full.

The beautifully carved stone pillar was found during a salvage excavation in the northwestern part of Jerusalem, near the Jerusalem International Convention Center. The excavation, directed by Danit Levi, was in the process of uncovering a Hasmonean craftsman village, when one evening (earlier this year) the site was abuzz upon the discovery of ancient “graffiti” on a stone object. The “graffiti” turned out to be a carefully engraved stone column that was unveiled to the public for the first time this Tuesday, at its new display location in the Israel Museum.

The 80-centimeter-high column, dated to circa 100 b.c.e., was written in a mixture of Aramaic and Hebrew, though it is generally classed as an Aramaic inscription—the Hebrew part making up the full spelling of Jerusalem. (The letters for both languages were the same, but represented a different vocabulary—i.e. the Aramaic bar for “son of,” rather than the Hebrew ben.) The inscription reads:

Hananiah, son of

Dodalos

Of Jerusalem

חנניה בר

דודלוס

מירושלים

While the stone column would have originally belonged to the workshop of the village Hasmonean artisan, it was found in secondary use in a wall used by the Roman Tenth Legion—the same legion that would go on to destroy Jerusalem in c.e. 70.

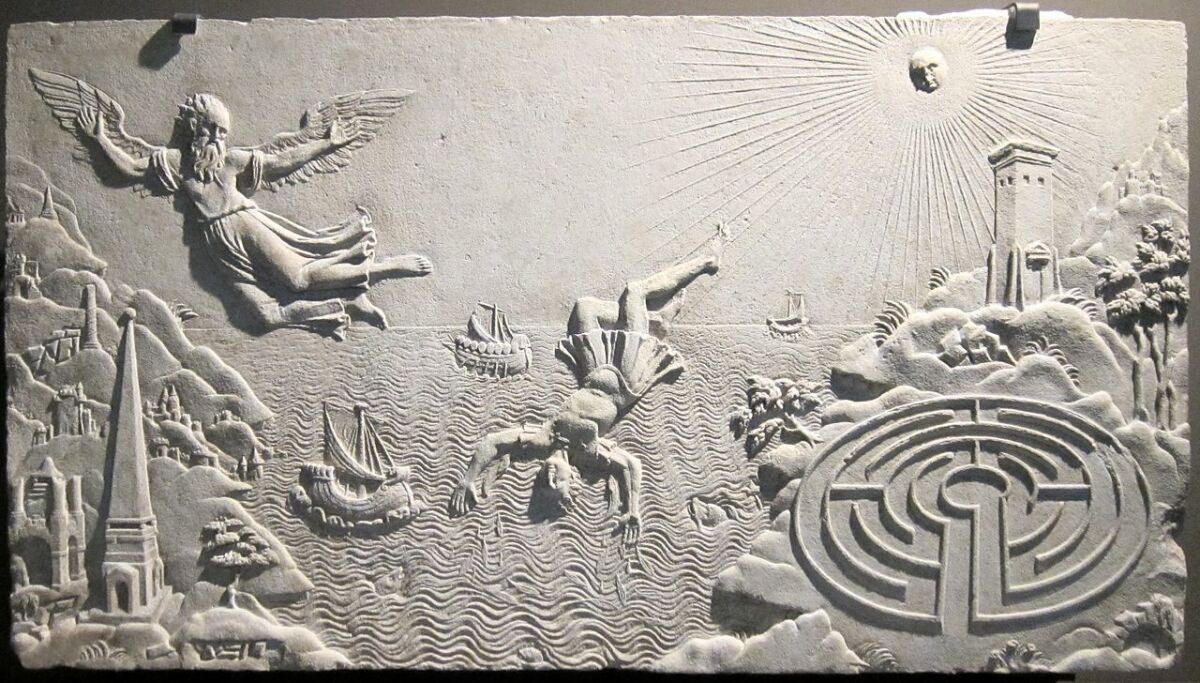

Scientists believe Hananiah was likely a potter that could have made vessels for Temple use (due to the nearby potters workshop uncovered). According to the archaeologists, the name given for his father, “Dodalos,” was simply a nickname for artisans of the time period, based on the mythological Greek craftsman Daedalus. (Daedalus is said to have built the Minotaur’s Labyrinth, as well as the famous wings for himself and his son Icarus to escape from their prison tower.) Finely crafted bowls and other objects were known in ancient Greek as daidala. Thus, the inscription helps to indicate Hananiah’s role as a craftsman, as well as the generally strong Hellenistic influence within Judea up to and during the Hasmonean period.

The remarkable new find adds further color to the picture of ancient Jewish Jerusalem. The discovery follows those of our own earlier excavation in Jerusalem’s Ophel this year (led by Dr. Eilat Mazar as well as Armstrong Institute staff), notably finding a large hoard of Year 4 Revolt coins from the final moments before Jerusalem’s fall at the hands of the Tenth Legion (you can read about the discovery here). In that excavation, numerous artifacts from the Hasmonean period were also discovered—items that would have been in use during the lifetime of Hananiah.

For more information on the wealth of artifacts discovered in Jerusalem—a vast number of which corroborate the biblical account—take a look at our article “Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem.”