The translators of the King James Version (kjv) of the Bible generally used apt and accurate words to translate the original Hebrew. But a few words stumped them. When they couldn’t find the appropriate term, they would simply transliterate the word into English. One example is the word tophet.

The exact meaning of tophet has been heavily debated. The book of Jeremiah records a tophet in the heart of Jerusalem. Jeremiah, Isaiah and Ezra describe the tophet as a place where Jews, in rebellion against the Torah, worshiped Molech and Baal, performed religious rituals, and even sacrificed their children.

But what exactly is the tophet? The archaeology of tophets powerfully illustrates the biblical account of the paganism that gripped Israel and Judah. It also reveals where the tophet originated.

Use in the Bible

The word “tophet” is used 10 times in the Hebrew Bible. In every scripture in which it is used, it is clearly being condemned. It is even used as a warning: “Thus will I do unto this place, saith the Lord, and to the inhabitants thereof, even making this city as Tophet; And the houses of Jerusalem, and the houses of the kings of Judah, shall be defiled as the place of Tophet, because of all the houses upon whose roofs they have burned incense unto all the host of heaven, and have poured out drink offerings unto other gods” (Jeremiah 19:12-13; kjv). For Jeremiah, the tophet was the epitome of horror and evil.

It was not an obscure place. In fact, it is alluded to around 25 times in the Bible. University of Pisa professor Paolo Xella wrote: “[I]f we collect all the relevant passages and analyze them thoroughly and synoptically, we will discover that no less than about 25 passages in the Old Testament testify more or less directly that Israelites and Canaanites (i.e. Phoenicians) sacrificed (and burned) their children … in tophet near Jerusalem” (‘Tophet’: An Overall Interpretation).

We know the tophet was located near Jerusalem, but can we be more specific about its location?

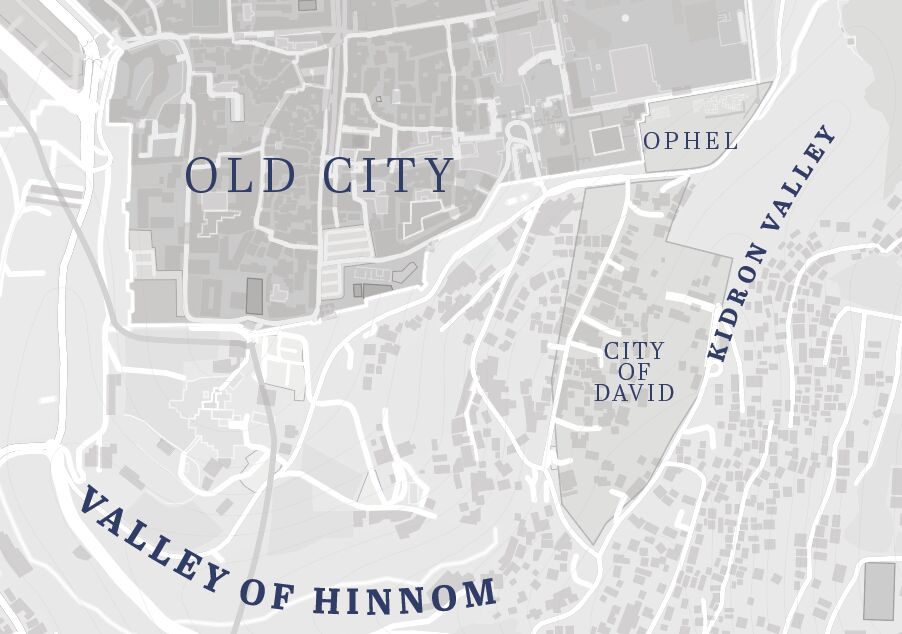

2 Kings 23:10 says the tophet was “in the valley of the children of Hinnom” (see also Jeremiah 7:31). The Valley of Hinnom runs south and east of the oldest section of Jerusalem (for more information, see sidebar after this article). The biblical text identifies Hinnom as a refuse site, or garbage dump. In the New Testament, Jesus called the Valley of Hinnom “Gehenna” 10 times, referring to it as a place of burning and destruction. Though Gehenna simply means “valley of (the son of) Hinnom,” it is translated in the kjv as hell. According to Thayer’s Greek Dictionary: “This was originally the Valley of Hinnom, south of Jerusalem, where the filth and dead animals of the city were cast out and burned; a fit symbol of the wicked and their future destruction.” This, then, was a perfect location for such heinous evils to be carried out.

The etymology of the Hebrew word tophet is less clear. There are a couple hypotheses, however. Rashi, a prominent rabbi from the 11th century c.e., wrote, “It is named תפת [tophet] because priests would bang on drums תופים [tophim] so that the father should not hear the groans of the child when he was burned by the pagan image.” In 1887, William Robertson Smith proposed that it may come from a Hebrew or Aramaic word meaning hearth or fireplace (referenced in La gorge géhennique, by Prof. Robert Kerr).

The exact meaning is unclear, but the Bible is not: Horrible evils, often involving fire, occurred at the tophet (e.g. Jeremiah 7:31).

The Bible connects the tophet with the heinous act of child sacrifice. On 11 different occasions the Bible says Israelites made their children to “pass through the fire” (e.g. Ezekiel 20:31; Jeremiah 32:35—see kjv). The Prophet Jeremiah rebuked the inhabitants of Jerusalem because they “filled this place with the blood of innocents; and have built the high places of Baal, to burn their sons in the fire for burnt-offerings unto Baal; which I commanded not, nor spoke it, neither came it into My mind” (Jeremiah 19:4-5).

The Bible does not provide much more information about what occurred at the tophet, but classical history does. Classical historians have even identified where this practice originated. Although the “tophet” still has not been discovered archaeologically in Jerusalem, classical history has assisted in the discovery of other locations, which can unlock our understanding of the one that once stood in Jerusalem.

Classical History of the Tophet

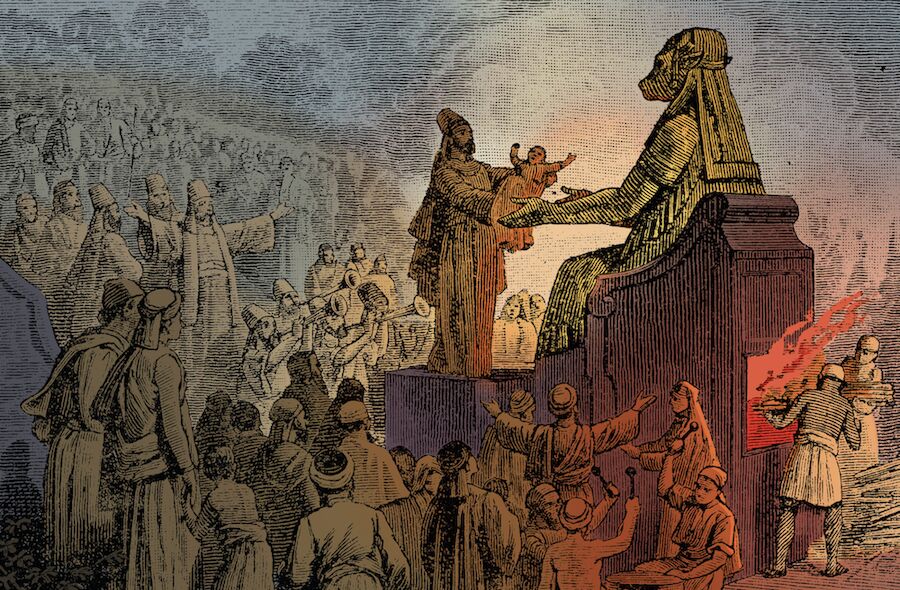

Diodorus Siculus, a Greek historian in Sicily from the first century b.c.e., wrote about ritualistic child sacrifice to Kronos (the Greek counterpart to Baal) in Carthage, saying: “There was in the city a bronze image of Kronos, extending its hands, palms up and sloping toward the ground, so that each of the children when placed thereon rolled down and fell into a sort of gaping pit filled with fire” (Bibliotheca, book xx, chapter 14).

Cleitarchus, a mid-fourth-century b.c.e. Greek historian, wrote a remarkably similar account: “Out of reverence for Kronos, the Phoenicians, and especially the Carthaginians, whenever they seek to obtain some great favor, vow one of their children, burning it as a sacrifice to the deity, if they are especially eager to gain success. There stands in their midst a bronze statue of Kronos, its hands extended over a bronze brazier, the flames of which engulf the child.”

Tertullian, who lived in Carthage in the second century c.e., wrote, “In Africa infants used to be sacrificed to Saturn [the Roman equivalent of the Greek Kronos], and quite openly …. Saturn did not spare his own children … their own parents offered them to him” (Apology, 9.2-3).

Plato wrote about the practice in his famous dialogue Minos: “With us [the Greeks], for instance, human sacrifice is not legal, but unholy, whereas the Carthaginians perform it as a thing they account holy and legal, and that too when some of them sacrifice even their own sons to Cronos [Kronos].”

The Bible and classical historians agree: The tophet was a place of slaughter of young children for religious rites. Professor Xella wrote, “[I]f analyzed comprehensively and without prejudice, both biblical and classical sources provide evidence for actual human sacrifices, where the victims are children killed and offered as a holocaust to the god Baal (Hammon), Greek Kronos, Latin Saturnus.”

Some scholars have dismissed the accounts of classical historians and the Bible, claiming these accounts are anti-Carthaginian and anti-Canaanite. Yet all the evidence points to the reality of child sacrifice. For such a wide variety of historians, in Judah and across the Mediterranean, to write so uniformly on the matter indicates this is more than anti-Carthaginian bias.

But we do not have to rely solely on classical or biblical history; we can also look to archaeology.

Archaeology of the Tophet

The Carthaginians were a Punic people, meaning they descended from the Phoenicians. The Phoenicians were a Canaanite-ish people who lived in city-states on the coast in the north of Israel (in the area of modern-day Lebanon). The Bible records many interactions between Israel and the Phoenicians. Some of those interactions are positive, such as in the case of Hiram, king of Tyre, who assisted King David in the construction of his palace and King Solomon in the construction of the temple. But Israel’s interactions with the Phoenicians weren’t all positive.

Jezebel was a Phoenician princess who married Israel’s King Ahab. 1 Kings 21:25 says the wickedness of Ahab was “stirred up” by Jezebel. This Phoenician princess introduced many pagan religious teachings and practices into the nation of Israel. Could this have included the heinous practices associated with tophets?

Oxford professor Josephine C. Quinn wrote that tophets were “found in central Mediterranean sites associated with the Phoenician diaspora, including Carthage and Hadrumetum in Africa as well as Sulcis, Nora, Harros and Monte Sirai on Sardinia, Mozia on Sicily, and Rabat on Malta. Urns containing the cremated remains of infants and animals are buried in these ‘tophets,’ and in most cases their surfaces are littered with stone markers” (“The Cultures of the Tophet,” 2011). Every location we know of where Phoenicians migrated—North Africa, Sardinia, Sicily and Malta—we find tophets.

The largest and oldest tophet ever discovered was publicized in 1921, when a Frenchman interested in archaeology witnessed antique smugglers digging up stelae outside of the walls of ancient Carthage—which was built by the Phoenicians. These stelae came from a tophet dated to the late ninth and early eighth centuries b.c.e., which continued to be used until the Romans destroyed Carthage in 146 b.c.e. This tophet was established within two generations of the founding of Carthage, indicating that the Carthaginians had brought this practice with them from their homeland. This site was massive, growing over time to encompass over 6,000 square meters.

Professors Lawrence Stager and Samuel Wolff wrote, “We estimate that as many as 20,000 urns may have been deposited there between 400 and 200 b.c. Clearly the deposits were not a casual or sporadic occurrence” (“Child Sacrifice at Carthage,” Biblical Archaeology Review, January-February 1984). The urns contained bones of both male and female children of varying ages. Over 6,000 stelae were also uncovered, many of which contained religious messages. Tophets from two other Phoenician sites—Mozia, Sicily, and Sulcis, Sardinia—date to the same period and exhibit similar finds.

Thousands of commemorative votives have been discovered at these sites. These votives are religious in nature. One such votive from Carthage reads, “To the lady Tanit face of Baal and to the lord to Baal Hammon ….” These are gods commonly discussed in conjunction with Phoenician and Canaanite culture. Baal is mentioned alongside the tophet in the Bible (Jeremiah 19). These votives “provide consistent proof that the archaeological areas called tophet were sanctuaries and that the rites performed in them were sacrifices,” wrote professors Jose Lopez and Mariagiulia Amadasi in “The Epigraphy of the Tophet.”

Tens of thousands of urns have also been discovered at these tophets. Some urns were filled with animal bones. Animal bones were only placed in urns when they had been offered as a sacrifice. When combined with the votives, it’s clear all of the urns in these tophets were filled with sacrificial bones. Offering a stillborn or dead child would not be considered a sacrifice; therefore, the children would have been alive when they were given as burnt offerings, as the classical historians recorded.

Stager and Wolff describe the Carthaginian tophet as being located in an open-air precinct enclosed by a thick wall evidenced by a foundation trench. Lopez and Amadasi wrote that tophets “are always—essentially—open-air sites constantly located on the margins of towns. … The tophet is to be interpreted as a special sacred area, dedicated to the offering of newborn babies or infants of various ages (or of animals as substitutes) as a sacrifice to the deity.”

About 35 sanctuaries, or tophets, have been discovered in Africa, most of which date to the third century b.c.e. or later. The majority of these sites would have been inhabited by ethnic Carthaginians, or Phoenicians. Professor Quinn stated, “These later African sanctuaries operate in a very similar way to the tophet at Carthage.”

Quinn wrote that at all of these African or Punic tophets “[t]here were large-scale ‘public works’ that suggest that the sanctuary was administered, whether by religious or civil authorities.” This is likely why the Bible highlights a few Israelite kings—notably Ahaz and Manasseh—as being patrons of the tophet in Jerusalem.

Biblical Link

Though no tophets have been uncovered in the Phoenician homeland, the archaeology of Punic colonies links the tophet back to it. Prof. Yigael Yadin wrote, “It is quite clear that the Punic (Carthaginian) culture preserved elements of the Phoenician culture, and the latter was definitely influenced by Canaanite elements.”

We don’t know exactly when Canaanite culture began the practice of child sacrifice. However, the Bible relates that it was already in existence by the time of Moses. This pagan practice is surely one reason for the command explicitly forbidding child sacrifice in the law of Moses. In Leviticus 20:2, Moses wrote: “Moreover, thou shalt say to the children of Israel: Whosoever he be of the children of Israel, or of the strangers that sojourn in Israel, that giveth of his seed unto Molech; he shall surely be put to death; the people of the land shall stone him with stones.” This command is repeated in Leviticus 18:21.

Deuteronomy 18:10 provides a complimentary law: “There shall not be found among you any one that maketh his son or his daughter to pass through the fire ….” In Deuteronomy 12:30-31, Moses even identifies where the Israelites would get these heinous practices: “[T]ake heed to thyself that thou be not ensnared to follow them, after that they are destroyed from before thee; and that thou inquire not after their gods, saying: ‘How used these nations to serve their gods? even so will I do likewise.’ Thou shalt not do so unto the Lord thy God; for every abomination to the Lord, which He hateth, have they done unto their gods; for even their sons and their daughters do they burn in the fire to their gods.” These scriptures indicate that the practices of the tophet and child sacrifice were already common among Canaanites during the second millennium b.c.e. Why else would Moses have so strongly and explicitly condemned them?

While archaeology has yet to reveal the tophet in the Valley of Hinnom, the excavation of Phoenician and Canaanite sites across the Mediterranean reveal evidence of ritualistic child sacrifice, the practice associated with the tophet in the Bible. Moreover, archaeology shows that this barbaric practice was often carried out at a “place of worship” on the outskirts of the city.

The word tophet in the Hebrew Bible has confused biblical scholars and been a subject of widespread debate. Need it be so complicated? We might not know the exact location of the tophet mentioned by Jeremiah in Jerusalem, and there might be some ambiguity around the meaning of the Hebrew word for tophet, but using the context of the biblical text, the archaeology of tophets across the region, and the references to tophets by classical historians, the meaning is clear: The tophet is a place of pagan worship of the most grisly and despicable manner.

Perhaps there is one bright side to this dark history: Even with the most detestable parts of Israel’s history, archaeology and even classical history corroborate the Bible as an accurate historical source.

Sidebar: The Valley of Hinnom

Ancient Jerusalem is situated on a hill between two valleys: Kidron and Hinnom. These two valleys are important to biblical history, much like the mountain itself (Mount Zion) on which the City of David, the Temple Mount and the Ophel are situated. The Valley of Hinnom, for its part, is filled with interesting history and symbolism.

Running southwest of the City of David, it intersects with the Kidron Valley on its eastern side. Hinnom, broader than the Kidron Valley, is called (biblically and in modern times) a gai (גיא), which can be defined as “a broad, open valley, not necessarily traversed by a running stream” (Prof. Lewis Bayles Paton, Jerusalem in Bible Times). The term Gehenna, or Gehinnom, is a conjunction of the words gai (valley) and Hinnom.

The term Gehenna has been used as a metonym for hell. This is largely because of the detestable history of the site. The Valley of Hinnom is infamous for being the biblical location of child sacrifice. Jeremiah recorded that the Jews “built the high places of Tophet, which is in the valley of the son of Hinnom, to burn their sons and their daughters in the fire; which I commanded them not, neither came it into my heart” (Jeremiah 7:31; King James Version). This horrific practice was condemned by the biblical authors.

American biblical scholars John McClintock and James Strong believe the Valley of Hinnom was ideally suited for the tophet, writing, “No spot could have been selected near the Holy City so well fitted for the perpetration of these horrid cruelties: the deep, retired glen, shut in by rugged cliffs, and the bleak mountain sides rising over all” (McClintock and Strong Biblical Cyclopedia).

King Josiah destroyed the tophet and desecrated the Valley of Hinnom (2 Kings 23:10-14; 2 Chronicles 34:4-5). From that point forward, Hinnom became a refuse dump. Scholars, such as Johannes Buxtorf, John Lightfoot and Ernest Wilhelm Hengstenberg, believe that a fire was almost always burning within the valley. In the New Testament, Jesus refers to it as a metaphor for continual fire. Medieval rabbi David Kimhi wrote that within Gehenna “fires perpetually burn in order to consume the filth and bones.”

Twentieth-century Scottish theologian William Barclay wrote that the site “was a foul, unclean place where loathsome worms bred on the refuse, and which smoked and smoldered at all times like some vast incinerator.” McClintock and Strong wrote that the valley “appears to have become the common cesspool of the city, into which its sewage was conducted, to be carried off by the waters of the Kidron, as well as a laystall, where all its solid filth was collected.” Being on the southwest side of Jerusalem, winds swept putrid odors away from the city’s inhabitants.

Before it became a hellscape, the Valley of Hinnom had served as a geographical border between two tribes of Israel. Joshua 15:8 and 18:16 describe the valley as the northern border of the tribe of Judah, putting the rest of Jerusalem in Benjamin’s territory.

The meaning of Hinnom is unclear. Many scriptures call this gorge “the valley of the son of Hinnom” or “Ben-Hinnom,” implying that Hinnom was the name of a patriarch and his son was a notable individual. He was most likely a Jebusite. Joshua’s account shows that the valley was already named after the son of Hinnom when Israel entered Canaan and the Jebusites inhabited Jerusalem.

Right after condemning the horrific practices that occurred in the Valley of Hinnom, the Prophet Jeremiah wrote, “Therefore, behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that it shall no more be called Tophet, nor the valley of the son of Hinnom, but the valley of slaughter: for they shall bury in Tophet, till there be no place” (Jeremiah 7:32; kjv). This final prophetic clause has been fulfilled. Today, the sides of the valley are dotted with graves. These tombs have provided some amazing archaeological discoveries, including the Ketef Hinnom Scrolls, which are among the most important finds in biblical archaeology. These two silver scrolls are the oldest Hebrew manuscript of biblical text, dating to the seventh century b.c.e. (see our article, “The Ketef Hinnom Scrolls: Earliest Biblical Text Ever Discovered!”)

In 70 c.e., the Romans sacked Jerusalem. Josephus states that the bodies of the slain Jews were thrown into the Valley of Hinnom (War of the Jews, 6.8.5 and 5.12.7). The last struggle of the uprising also occurred in the valley itself. These events further contributed to the dismal symbolism of Hinnom in Judaism and Christianity.

Shortly after the 70 c.e. holocaust, the location of Hinnom was lost. The valley was later named Wady er-Rabbabi. By the 19th century, when biblical enthusiasts and scholars set out to map the Holy Land, the exact identity of the Valley of Hinnom was unknown and debated for decades. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, scholars confused the Valley of Hinnom with the Kidron Valley and the Tyropoeon Valley (which ran west of the original city). The location of Hinnom was not confirmed until archaeologists settled the debate about the location of Mount Zion.

Today, Hinnom is becoming a center for tourism. The City of David Foundation has established a project called “Farm in the Valley,” which features a waterfall, flower garden and several other biblical crops. This site allows tourists to learn about the agricultural crafts and practices that ancient Israelites used thousands of years ago. The site is free to visit.

Carpeted in green grass, the Valley of Hinnom is now a beautiful place to visit. The City of David project is beautifying Hinnom in direct opposition to its long and disturbing history.