The Bible clearly says that in the late eighth century b.c.e., the Assyrian Empire deported the people of Israel from their towns and filled them with people from from Babylon and Akkad (2 Kings 17:6, 24). This is how the lost 10 tribes of Israel became lost. This deportation policy is demonstrated in the archaeology of Tel Hadid.

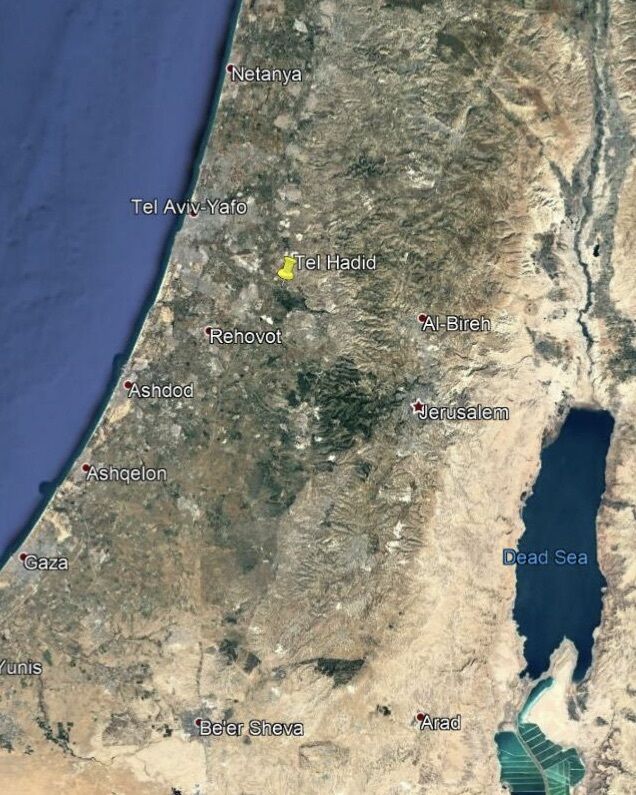

Tel Hadid is an archaeological site in the Shephelah (foothills of Judah and Israel west of Jerusalem). The city is a few miles north of Tel Gezer, a recognized border town between Israel and Judah. Tel Hadid overlooks the Via Maris (trade route that runs through the coastal plain), the Lydda Valley, the Al Jib plateau, Tel Aviv and the hills of Samaria, making it a valuable hill for surveying these crucial parts of Israel and Judah.

According to Tel Hadid senior staff member Noa Ranzer, the site’s earliest remains date to the Intermediate Bronze Age (2500–2000 b.c.e.). It was continually inhabited throughout the Bronze and Iron ages. It is mentioned three times in the Bible as a city the Jews returned to after the Babylonian captivity (Ezra 2:33; Nehemiah 7:37; 11:34). The city (Greek: Αδιδα) was later fortified by Simeon Maccabeus while fighting Diodotus Tryphon in the valley below the city. Hadid is also mentioned on the Madaba map—the oldest map of the Holy Land—and was blockaded by Roman general and emperor Vespasian as he besieged Jerusalem. It was later renamed Al-Haditha and operated as an inhabited village until the 1948 Israeli War of Independence. Today, the Hadid moshav is about a mile away from Al-Haditha.

Assyrian Archaeology at Tel Hadid

Tel Hadid’s most interesting history is in the eighth and seventh centuries b.c.e. In that period, it is believed to have been an Assyrian provisions center in Israel. “Finds at Tel Hadid, west of the Samaria hills, may be identified as the remains of an Assyrian bīt mardīte, a roadside provisioning center for Assyrian officials, messengers and troops,” Prof. Shawn Zelig Aster wrote (“An Assyrian Bīt Mardīte Near Tel Hadid?”). Hadid was undoubtedly chosen for its geographical situation.

“No wonder the Assyrians invested great efforts in reviving the settlements in the region following their conquest of the kingdom of Israel,” Tel Aviv University professor and site excavator Ido Koch wrote. “With its central location, the region of Tel Hadid and Tel Gezer played a crucial role connecting the Assyrian army and administration to the city of Gaza, a prime objective of the Assyrian colonial efforts ever since Tiglath-pileser iii’s first campaign to the region in 734 b.c.e.” (“Forced Resettlement and Immigration at Tel Hadid”).

Assyria did more than conquer the Hadid region. The Assyrian Empire was famous for deporting inhabitants out of a region and replacing them with people from their own empire. This practice is clearly recorded in the Bible: “So Israel was carried away out of their own land to Assyria, unto this day. And the king of Assyria brought men from Babylon, and from Cuthah, and from Avva, and from Hamath and Sepharvaim, and placed them in the cities of Samaria instead of the children of Israel; and they possessed Samaria, and dwelt in the cities thereof” (2 Kings 17:23-24). Hadid has provided a slew of artifacts indicating it was occupied by people from the Assyrian Empire, originating from exactly where the Bible says in the seventh century b.c.e.

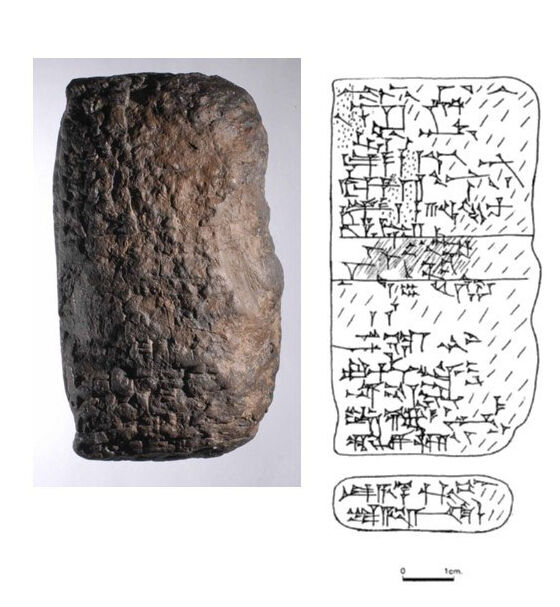

The two most compelling artifacts are business documents. One of these documents dates to the autumn of 698 b.c.e. It’s a bill of sale for a piece of land. This document includes the common Mesopotamian practice of conducting a transfer of title in front of seven or more witnesses (eight are listed on this particular document). The man purchasing the land for 1 mina of silver was named Marduk-bela-uṣur.

The other document is from the spring of 664 b.c.e., and it details the granting of a loan. The names on the tablets are not Israelite. Rather, they are names from the lands listed in 2 Kings 17:24. “The individuals mentioned in both documents have Akkadian (perhaps Babylonian) and Aramean names,” wrote Professor Koch, “no names with Yahwistic components (names formed on the divine name Yahweh) appear in the text.” These people had been relocated from the Assyrian Empire and were conducting business the Mesopotamian way.

The deportees were clearly from the land of Babylon and its vicinity, just as 2 Kings 17:24 says. Renowned Israeli archaeologist and historian Nadav Na’aman wrote, “All five places mentioned [in 2 Kings 17:24] are located either in the center of Babylonia (namely, Babylon and Cutha) or in peripheral areas southeast of Babylonia. … The deportees from the named places were settled in both the capital city of Samaria and its rural villages.” Tel Hadid was one of these villages.

Similar Finds at Other Sites

Tel Hadid is not the only site to yield Assyrian finds pointing to the origin of the Samaritan people. Tel Gezer has produced numerous similar finds. “Two cuneiform sale contracts have been discovered in the excavations of Gezer,” Professor Na’aman wrote. “The juridical procedures and language used in the tablets from Gezer and Tel Hadid are Assyrian. … The Babylonian character of the personal names from the Tel Hadid and Gezer tablets is self-evident.”

A Neo-Assyrian tablet was also found from this period at Khirbet Kusiya, which is 31 miles north of Tel Hadid near the Via Maris from Jezreel to Gaza. The tablet documents another land sale. A seal impression on the tablet also belies its Babylonian origin. “The three sites where cuneiform tablets have been discovered are among the places where Sargon settled the Babylonians and Elamites he deported in his late years,” wrote Professor Na’aman. Fragmentary Assyrian stelae were also discovered at two other sites, Qaqun and Ben Shemen.

The existence of cuneiform script at Gezer and Khusiya indicates that these deportees were clinging to their own cultures, rather than yielding to the more functional alphabetic script. “The Babylonian deportees to the province of Samaria arrived from the ancient and most respected centers of learning and culture of Mesopotamia and, being proud of their origin, kept the cultural tradition of their ancestors,” Na’aman wrote.

Chronology of Deportation

The relocation process did not happen immediately after Israel’s fall; it was a mass effort that would have taken some time. Also, it was generally rebellious peoples who were deported to other lands, meaning that Israel would have been reoccupied with whoever rebelled next. The Bible says that polity was Babylon.

Babylon had to be reconquered three times in the eighth and seventh centuries: in 709 b.c.e. by Sargon ii, in 689 b.c.e. by Sennacherib, and in 648 b.c.e by Ashurbanipal. The discovery of Babylonian text in Hadid from 698 b.c.e. shows that it was the earliest of these three kings who sent deportees to Samaria. “It is probable, although not certain, that the Northern Babylonian people settled in Samaria were taken as a consequence of Sargon’s recapture of the region between 710 and 708 b.c.e.,” wrote Assyriologist Karen Radner. Sargon himself wrote about this on two separate inscriptions—the Khorsabad annals and the Nimrud prism—saying, “I again settled Samaria, more than (it had) previously (been settled)” (translation from Prof. Shawn Zelig Aster).

Ezra 4:2 is a unique scripture that shows this deportation process occurred over a long period. There, the Samaritans recount their own history to the returning Jews: “Now when the adversaries of Judah and Benjamin heard that the children of the captivity were building a temple unto the Lord, the God of Israel; then they drew near to Zerubbabel, and to the heads of fathers’ houses, and said unto them: ‘Let us build with you; for we seek your God, as ye do; and we do sacrifice unto Him since the days of Esarhaddon king of Assyria, who brought us up hither’” (Ezra 4:1-2).

Who were these adversaries? “While any attempt to uncover the historical identity of the ‘adversaries’ is necessarily complex, within the narrative itself it makes most sense to interpret them as Samaritans,” theologian Edward Green wrote. These Samaritans believed they had been in their lands and worshiping Yahweh since the times of Esarhaddon, who the Bible describes as one of Sennacherib’s sons (2 Kings 19:37). Esarhaddon claimed the throne of Assyria in 681 b.c.e., after his brothers slew his father and tried to claim the throne for themselves.

That year, 681 b.c.e., was 18 years after the bill-of-sale document found at Hadid. This can indicate two things. First, deportation was a gradual process. Israeli Assyriologist Hayim Tadmor wrote, “The statement in Ezra 4:2 implies that the process of transplantation of exiles into Samaria still continued at the time of Esarhaddon” (“The Campaigns of Sargon II of Assur”). These Babylonians may not have been moved to Samaria until 681 b.c.e or later though they were conquered by Sennacherib in 689 or by Sargon II in 709.

Secondly, in Ezra 4:2, the Samaritans are saying that the days of Esarhaddon are when they began to sacrifice to Yahweh. The existence of a Marduk-based name on the 698 b.c.e. tablet is not surprising then. The mixing of cultures is also a long, gradual process. Only after 18 years or more in the land did the Assyrians start to seek the God of the land, the God of Israel.

All of this matches the account in 2 Kings 17 extremely well: “And so it was, at the beginning of their dwelling there, that they feared not the Lord; therefore the Lord sent lions among them, which killed some of them. Wherefore they spoke to the king of Assyria, saying: ‘The nations which thou hast carried away, and placed in the cities of Samaria, know not the manner of the God of the land; therefore He hath sent lions among them, and, behold, they slay them, because they know not the manner of the God of the land’” (verses 25-26).

Notice that the Samaritans did not seek the God of Israel at the beginning of their dwelling in Samaria—only after wild animals attacked them did they begin to turn. The abundance of lions may also suggest that after the land’s inhabitants had been deported, it took a while for new peoples to arrive—allowing animals to occupy towns and villages. “So one of the priests whom they had carried away from Samaria came and dwelt in Beth-el, and taught them how they should fear the Lord. Howbeit every nation made gods of their own, and put them in the houses of the high places which the Samaritans had made, every nation in their cities wherein they dwelt” (2 Kings 17:28-29).

These details match perfectly the discoveries at Tel Hadid and other sites yielding seventh-century b.c.e. Assyrian artifacts. The Bible and archaeology agree that the Israelites were deported from the lands of Samaria and replaced with deportees from the lands surrounding Babylon. The population deportation policies of the Assyrian Empire down to the origin of the importees, as described in the Bible, can be soundly supported by the archaeology of valuable sites in Israel like Tel Hadid.