The Dead Sea Scrolls remain one of the premier discoveries in biblical archaeology. Until their discovery (the first of which was discovered in 1946), the earliest-known complete or near-complete Hebrew language biblical manuscripts available dated to just over 1,000 years ago—the 10th century c.e. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls pushed that date back more than a millennium—to the final centuries of the first millennium b.c.e.

But for all the justifiable excitement and drama surrounding the Dead Sea Scrolls, they are not the earliest examples of biblical Hebrew text available to us. That record is claimed by another remarkable, yet often-overlooked, discovery made in 1979, which predates the Dead Sea Scrolls by 500 years. These texts, while far more miniature and fragmentary, date to the First Temple Period and match letter-for-letter text found in four different biblical passages. They represent the earliest biblical text ever discovered and constitute one of the most significant biblical archaeology discoveries of all time.

They are known as the Ketef Hinnom Scrolls (alternately as the Priestly Blessing Scrolls or Silver Scrolls).

In this article, we’ll review the scrolls—their dramatic discovery and curious nature—as well as just how closely their text matches that of the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible.

A Most Unexpected Discovery

Israeli archaeologist Prof. Gabriel Barkay, who turned 80 this year, is sometimes affectionately referred to as the “dean of biblical archaeology” (a title formerly applied to the late, great Prof. Benjamin Mazar). In 1979, Professor Barkay began excavations on the western edge of Jerusalem’s Hinnom Valley (“Ketef Hinnom” meaning “shoulder of Hinnom”—along the upper part of the valley’s steep western edge). The location was an ancient tomb area adjacent to the modern St. Andrew’s church.

Professor Barkay was working with a team of youth archaeologists at the time. He later described the discovery of the scrolls rather humorously in an interview with tour guide Gila Yudkin: “We excavated by the outer apse of the present-day church. The graves were in bad shape with collapsed roofs. The caves had all been looted. … [W]e discovered a repository where they buried the bones and I looked into that repository and saw something that looked like a rock floor. I was disappointed.

Among the 13-year-old diggers, there was one annoying kid named Nathan, who was always tugging at my shirt. I thought this was an ideal place to put him—he would be out of my sight. I told Nathan the repository had to be as clean as his mother’s kitchen, even if he had to lick it. It had to be clean for the photography. Not too long afterwards, I felt him tugging at my shirt again. Nathan had in his hand almost complete pottery vessels. This time, I pulled at his shirt, took him back to the area, and asked where he found them. Bored, Nathan had banged on the floor with a hammer. Under the rocks, he found the pottery.

Little Nathan was sent home with his peers. Then I recruited archaeology students from Tel Aviv and Jerusalem and we worked 24 hours around the clock. In one chamber more than a thousand objects were found. They included 125 objects of silver, 40 iron arrowheads, gold, ivory, glass, bone and 150 semiprecious stones. There was 60 centimeters [2 feet] of accumulation filled with objects and skeletal remains. There was a lot of dust and a lack of oxygen. It was very hot. We had to change teams every few hours. … Everyone was sworn to secrecy—they weren’t allowed to tell parents, spouses or friends. If word got around Jerusalem that there was such a treasure, the California gold rush would be nothing compared to what would happen here.

Among the treasures discovered in the burial cave were two objects that looked like “cigarette butts.” Upon closer inspection, they turned out to be extremely tiny, tightly rolled silver scrolls. They were 99 percent pure silver.

Given the tiny, brittle nature of the scrolls—one is 27 millimeters wide, the other is just 11 millimeters—the task of unrolling them was extremely risky. The scrolls were sent to universities in Britain and Germany, both of which refused to open them because such an operation was “too risky” and would damage the items entirely. Finally, the scrolls were given to the Israel Museum, where conservator Joseph Shenhav came up with a genius way of opening them. First, he soaked the items in a special acid solution to remove corrosion. After this, he applied a strong elastic emulsion to the exposed back surface, providing a strong and supple support to the artifacts as they were gradually unwound (an excruciatingly slow process that went on for months).

The newly opened scrolls, to Barkay’s joy, each revealed paleo-Hebrew text from top to bottom. Now the task was to put each scroll under the microscope to decipher them—quite literally. Ketef Hinnom i, the larger of the two, measures just 97 by 29 millimeters unrolled, and Ketef Hinnom ii measures a minuscule 39 by 11 millimeters.

No one could have expected the significance of what was inscribed: They bore the earliest biblical texts ever discovered. As The Incredible Journey’s “The Mystery of the Silver Scrolls” wryly summarized: “Leave it to a 13-year-old troublemaker to make one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of all time”!

Publication—Pushback—and Republication

The two inscriptions were originally published in Hebrew by Professor Barkay in 1989. In 1992, an updated English version was published; the report was titled “The Priestly Benediction on Silver Plaques From Ketef Hinnom in Jerusalem.” This initial research dated the scrolls, based on paleography and context, to the seventh century b.c.e. It also highlighted scriptural parallels between the inscriptions and the Hebrew Bible, particularly the book of Numbers.

There was significant pushback from certain scholars who advocated reassigning the scrolls to a much later date, perhaps in the Persian Period or even deep into the Hellenistic Period. Part of the intrigue is that one of the Mosaic Torah passages found on the scrolls is dated, according to the infamous minimalist Documentary Hypothesis (which theorizes a much later formulation of the biblical texts) to long after the time period of the scrolls.

This pushback prompted a major reanalysis of the scrolls by Barkay and his colleagues. This was necessary, they wrote in 2004, because “although the vast majority of scholars support the late Iron Age date for the artifacts, a vocal minority of scholars persists in advocating a later date” (“The Amulets From Ketef Hinnom: A New Edition and Evaluation,” by Barkay, Marilyn Lundberg, Andrew Vaughn and Bruce Zuckerman, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research; emphasis added). This 2004 article presented new analysis that reinforced the dating of the scrolls to the late Iron Age, just prior to the Babylonian destruction.

This assessment, wrote Prof. P. Kyle McCarter Jr., “settle[s] any controversy” over the dating of the inscriptions.

This 2004 article, which also highlighted traces of letters not previously identified in the earlier analysis, will serve as our guide in examining the inscriptional content on the artifacts (with text examples following those that were produced by Barkay, Lundberg, Vaughn and Zuckerman).

Scrolls of ‘Confession’ and ‘Benediction’

Both scrolls, Ketef Hinnom i and ii, are funerary amulets. Each contains “blessings,” as well as professions of faith, paralleling passages found in the Bible.

The scrolls are written in the original paleo-Hebrew script, a more angular script (the same Hebrew-Phoenician script from which the English alphabet derives). Over the course of the post-exilic period, this script changed into the Aramaic script (adopted during the exile) and then into the same square script used in the Masoretic Text of our Hebrew Bibles to this day. (Note: Even though the shapes of the letters evolved, the structure of the biblical Hebrew text remained the same.)

The majority of the textual content on each scroll is an excerpt of the so-called “Priestly Blessing” text found in Numbers 6:24-26. This is why the scrolls are commonly called the “Priestly Blessing Scrolls.” Both scrolls also bear other texts, including text found in three other parallel biblical passages. This text can be found in the introductory text of the larger amulet of the two, Ketef Hinnom i, which we will examine first.

Amulet i: The ‘Confession’

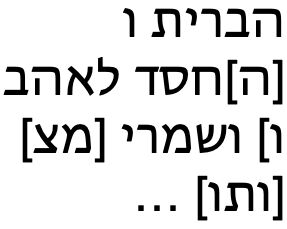

Lines 1 through 3 of Ketef Hinnom i are poorly preserved, and it is next to impossible to restore the text found on these lines. Beginning with line 4, however, we start to see our first clearly legible passage. This text is referred to by the 2004 authors as a “confessional statement [paralleling] verses found in Deuteronomy 7:9, Nehemiah 1:5 and Daniel 9:4, in which blessing from the Lord is made conditional upon obedience to the covenant and the commands from Yahweh.”

This text, as it appears on the inscription, is shown below, transposing the paleo-Hebrew text into its square script equivalent. Note that the scrolls are extremely fragmentary and are damaged along their edges; missing or partial letters are restored by the authors within brackets, although there is certainly more room for debate about these edge letters. (Also note that in ancient Hebrew it was not unusual to split words into new lines.)

This text is the famous biblical statement (with the passage preserved on the scroll italicized), “God, who keepeth covenant and mercy with them that love Him and keep His commandments.” This statement is found in three parallel biblical passages—Deuteronomy 7:9, Nehemiah 1:5 and Daniel 9:4. There are slight differences between these three biblical texts, with different beginnings and endings. For example, Deuteronomy has “the faithful God” while Nehemiah and Daniel both state “the great and awful God.” Though the upper lines of the scroll are extremely fragmentary, it is possible that the text aligns more closely with the Nehemiah and Daniel passages, based on the extremely fragmentary remains of what could be the word “great” (גדול) in line 3.

Below is the equivalent Masoretic Text (in this case, from Deuteronomy 7:9; note that in the Nehemiah and Daniel passages, the final word is suffixed slightly differently as מצותיו rather than מצותו; although the meaning is exactly the same. The authors identify the latter as the best fit for what would have been contained on the scroll—still, this area is obscured by the scroll’s damaged periphery). The letters in black are those that are clearly preserved on the scroll; letters in green are those obscured or damaged on the fragmentary edges of the scroll; letters in red are those not found on the scroll.

The parallel with the biblical text is remarkable. Of the nearly 20 preserved letters, only one letter (ל) is different from the biblical text. This omitted prefix letter—essentially meaning “to” or “with”—does not change the meaning of the passage. In fact, it would be a logical choice for the amulet, given the limited writing area available. Effectively, the omission of this letter changes the passage from saying to them that love Him and to them that keep His commandments to simply, to them that love Him and them that keep His commandments. (Even in many Bible translations, this secondary “to” or “with” is omitted, since it is implied.)

Given the minute size of the amulets, there are a few deliberate “shortcuts” in text. We will see a couple of additional examples as we proceed. Nonetheless, the overall letter accuracy of this 2,600-year-old amulet to that contained in the Masoretic Text that we use today is astonishing.

Amulet i: Intermediate Text

Lines 8 through 14 on Ketef Hinnom i contain an additional passage of text that is difficult to reconstruct in its entirety and that has no direct biblical parallels. The text is reconstructed by the authors as something like, “… the Eternal? … [the?] blessing more than any [sna]re and more than evil. For redemption is in him. For yhwh is our restorer [and] rock.”

Though there are no complete biblical parallels to this section of the amulet, similar themes and word usage can be found in Zechariah 10:6 and Psalm 80:4, 8 and 20 (in the jps; verses 3, 7 and 19 in most other translations). Barkay and his colleagues describe this in further detail in their 2004 report.

Amulet i: The ‘Benediction’

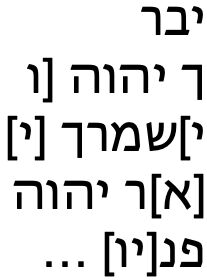

In lines 14 through 18 (the end text) of the first amulet, we have the famous “Priestly Benediction” or “Priestly Blessing” of Numbers 6. The text on the amulet is shown below, as provided in the 2004 publication.

This is the famous biblical statement (the passage preserved on the scroll italicized), “The Lord bless thee, and keep thee; The Lord make His face to shine upon thee, and be gracious unto thee” (Numbers 6:24-25). Verses 22-23 explain that this special “blessing” should be given to the Israelites by Aaron and his descendants. “And the Lord spoke unto Moses, saying: ‘Speak unto Aaron and unto his sons, saying: On this wise ye shall bless the children of Israel; ye shall say unto them.”

Below is the equivalent biblical text to that found on the scroll, taken from verses 24-25. Again, the letters in black are those that are clearly preserved on the scroll; letters in green are those obscured or damaged on the fragmentary edges of the scroll; letters in red are those not found on the scroll.

Here, again, is a remarkable letter-for-letter parallel with the biblical text. Note that the initial word in the biblical text contains an additional kaf (כ, or ך at the end of a word, in square-script Hebrew. The original paleo-Hebrew script does not have such differing end-forms for letters). This word is split across the damaged edges of the scroll at this point. While it can be argued that this additional kaf was originally present (thus shown in green), the authors believe there was only one, serving “double-duty”—part of the small scroll’s abbreviated nature. Even if not, here again, we have no difference in meaning—merely bless and keep you versus bless you and keep you.

Amulet ii: Introductory Text

It bears reemphasizing that the second amulet, Ketef Hinnom ii, is extraordinarily small—less than half as wide and half as long as the small Ketef Hinnom i. Like the center text of Ketef Hinnom i, the introductory text of Ketef Hinnom ii (lines 1-5) contains text not paralleled in full in any other biblical text. These lines are translated by the authors as follows: “May he/she be blessed by yhwh, the warrior/helper and the rebuker of evil.”

While there are no complete biblical parallels to this section of the amulet, there are similar biblical themes and word usages, such as that found in Zechariah 3:4 (as expounded upon by Barkay, Lundberg, Vaughn and Zuckerman).

Amulet ii: The Longer ‘Benediction’

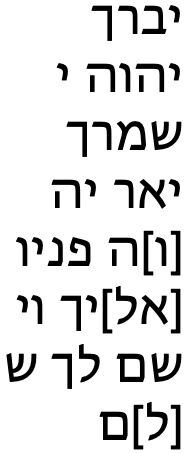

The remaining text on Ketef Hinnom ii (lines 5-12) bears the same “Priestly Benediction” found on Ketef Hinnom i, with a slight difference: In the case of this scroll, even more of the biblical blessing is given. Below is this text preserved on the scroll.

This represents the following from the wider blessing passage (preserved text italicized): “The Lord bless thee, and keep thee; The Lord make His face to shine upon thee, and be gracious unto thee; The Lord lift up His countenance upon thee, and give thee peace” (Numbers 6:24-26). The first part of verse 26 (unitalicized) is omitted on the scroll, with the artifact preserving what could be seen as an abbreviated form of the blessing, in jumping straight from “be gracious unto thee” to “and give thee peace.”

Following verse 26 in the biblical account—the end of the blessing—the passage concludes with the following instruction to Aaron and his sons: “So shall they put My name upon the children of Israel, and I will bless them” (verse 27). One imagines a descendant of Aaron doing the same for his deceased.

Below is the equivalent passage from the Masoretic Text—letters in black clearly preserved, letters in green obscured or damaged on the periphery, and letters in red not found on the scroll.

Again, the letter-for-letter exactness is extraordinary. We have one obvious difference—the lack of the prefix vav, ו, (meaning “and”) in the scroll. As with the earlier referenced prefix ל (meaning “to”) in Ketef Hinnom i, the omission of this prefix is not surprising, and it does not change the meaning—effectively going from the Lord bless thee, and keep thee, to the Lord bless thee, keep thee. And again, as with the first amulet, though it is edged by the fragmentary scroll border, the authors believe there was only one kaf at the end of the first word, serving as a double-duty abbreviation. They also believe the final word “peace” (שלום) was abbreviated without its mater lectionis “helper vowel,” ו (thus שלם). Yet this fragmentary word is split along the fringes of the artifact, so there is room to debate whether it was originally present or not; further, the word can be spelled with or without this letter.

Interestingly, there is a slight difference in the lettering of verse 25 between two of the major historical textual variants of the Bible—the Masoretic Text and the Samaritan Pentateuch. The Samaritan Pentateuch is the common name for the Torah belonging to the Samaritan community, regarded by adherents in the community to be the original as given to Moses (in the same manner that observant Jews, as well as many Christians, hold the Masoretic Text to be the original, divinely inspired text). Though both of these Torah texts are at least broadly the same, there are notable differences throughout (particularly in the case of the Ten Commandments—the Samaritan version including a mandate for the community’s iconic worship at Mount Gerizim).

When it comes to Numbers 6:25, the Masoretic’s “יאר” (meaning “to shine”) is given in the Samaritan Pentateuch as “יאיר.” The meaning is the same—the Samaritan merely contains the addition of another mater lectionis, the letter yod (י, signifying a longer “ee” pronunciation). Still, it is interesting to note that of these two textual variants, it is the Masoretic form that is preserved in these earliest discovered biblical texts.

Christian readers may find this ironic, in light of the famous New Testament passage: “For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot [Hebrew yod] or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled” (Matthew 5:18; King James Version). That it has not—in the case of the Masoretic version’s parallel to the Ketef Hinnom scrolls.

We are now nearing half a century since the discovery of the Ketef Hinnom Scrolls—and still they remain some of the greatest discoveries in biblical archaeology, right alongside the likes of the Tel Dan, Merneptah and Mesha stelae, as well as the Dead Sea Scrolls. Small wonder, then, that Professor Barkay—in his storied career in biblical archaeology—considers them “the most important find of my life.”

Although they contain no reference to any mighty biblical characters like David or Hezekiah found in other such inscriptions, they do bear witness to the early existence and circulation of these sacred biblical texts—the earliest direct scriptural parallels we have, from more than 2,600 years ago.