Milad Muadad Alsha’ar (10)

Alma Ayman Fakher Eldin (11)

Jafara Ibrahim (11)

Naji Taher Alhalabi (11)

Vinees Adham Alsafadi (11)

Iseel Nasha’at Ayoub (12)

Yazan Nayeif Abu Saleh (12)

Johnny Wadeea Ibrahim (13)

Hazem Akram Abu Saleh (15)

Ameer Rabeea Abu Saleh (16)

Fajer Laith Abu Saleh (16)

Nathem Fakher Saeb (16)

These are the names of the 12 children and teenagers killed on Saturday, July 27, after a Hezbollah rocket struck a soccer field in Majdal Shams, a Druze town located in the Golan Heights along Israel’s border with Syria. As video footage and testimony of the tragic event reveals, the youths had heard the air raid siren and were rushing to the gate to get to a nearby bomb shelter, when the rocket struck the exit point of the field. Forty-four more were wounded in the attack—the “most tragic day in the community’s history. … Even the village elders have no memory of such a large number of civilians killed at one time,” wrote Jack Khoury—“certainly not deaths of children, even during the 1967 Six-Day War,” in which the Golan Heights was a focal point of the conflict between Israel and Syria.

The unimaginable tragedy has brought into world focus a little-understood—and perhaps for most, altogether unknown—population known commonly as the Druze. It is a community that many in the media do not know what to do with; the Washington Post, for example, was widely derided on social media for an extraordinarily misleading front-page story featuring one of the mourning Druze families in their Muslim-style attire, followed by the bold headline “Israel Hits Targets in Lebanon.” Arab media sympathetic to Hezbollah initially celebrated the successful rocket salvo, but quickly retracted their statements upon seeing the Arab names of the victims. The backpedaling Hezbollah’s official position now is that the rocket was an Israeli Iron Dome misfire—a position that is hard to believe, given the pieces of the Iranian-made Falaq-1 rocket that have been retrieved from the soccer pitch.

On Tuesday, July 30, I traveled to Majdal Shams with a group of journalists to report on the events that took place and to hear speeches from the mayor and military leadership. Most reporters will tell a limited story of what happened to this Golan community over the weekend, or describe the event in the context of the last 10 months of conflict since October 7. Some will go as far as to describe events in the context of the Six-Day War and Israel’s capture of the Golan Heights in 1967. And most historians, in describing this ethnoreligious community, will begin with events taking place in the early 11th century c.e., during the rule of the Isma’ili Shia Fatimid Caliphate.

But even this is too late—more than 2,000 years too late.

Children of Shu’ayb—Jethro

Who, then, are the Druze? On a religious level, they are a unique group who venerate Moses, but are not Jews; who believe Jesus to be Messiah, but are not Christians; who believe Muhammad to be a prophet of God, but are not Muslims; who believe in reincarnation, but are not Buddhists; who follow the teachings of Pythagoras, but are not Pythagoreans. Confounding matters further, though the community is commonly known as “Druze”—a name derived from the early preacher ad-Darazi (a term first applied to them by an 11th-century Christian historian, Yahya of Antioch)—he is actually considered to be a heretic and a traitor, thus there is another name by which they refer to themselves.

Introducing al-Muwaḥḥidūn—“The Monotheists.”

The global Druze population numbers up to around 2 million, with the largest community living in Syria (~600,000), followed by Lebanon (~250,000), then Israel (~150,000), with a large diaspora living abroad, particularly in Venezuela (~60,000) and the United States (~50,000). On a regional level, the Druze territory is focused around the central Levant—southwestern Syria, southern Lebanon, and northern Israel (the Galilee and Golan communities).

Put most simply, the Druze are an Arab, Arabic-speaking people. Their five-color community flag is immediately recognizable, as is their symbol of the five-pointed, five-colored star—both of which represent the five “limits,” or metaphysical powers recognized in their religion. The community is rightly described as “ethnoreligious”—an ethnic religious group officially closed off to outsiders since 1043 c.e., into which none may convert—and intermarriage is forbidden.

It is in this formative Fatimid Islamic period, during the first decades of the 11th century c.e., that most of the conversation begins about the Druze. But this is not early enough.

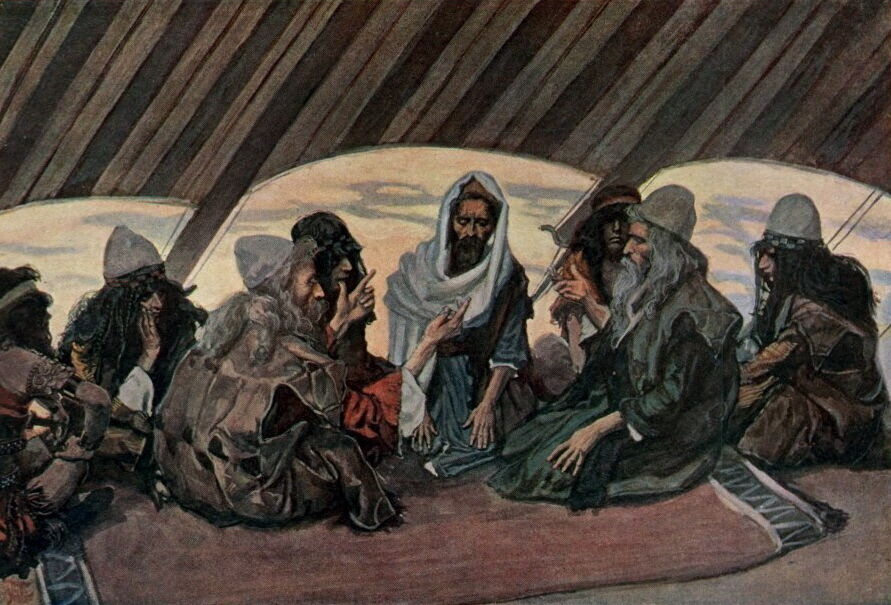

This was highlighted to a degree in an interesting 2021 Seekers of Unity podcast, which featured a very cordial sit down with Sheikh Professor Fadel Mansour, an elder of the Druze community in Israel. In the introduction, the interviewer asked the sheikh to describe “the history of the Druze, and where they come from within Islam, and how they differ.”

“It’s a long story,” the sheikh knowingly replied. “You see, we believe in Jethro, who was the father-in-law of Moses, 3,300 years ago. Jethro came with a message to all people ….”

Later, the interviewer asked again: “So, the way I understand it, and please correct me if I’m wrong, is that the beginning of the Druze faith breaks from Isma’ili Islam with the figure of Hamza ibn Ali ….”

“No, no, but before that, but before that,” the sheikh interjected. “The message of Jethro ….”

Indeed, there is no group that singularly has such devotion to the figure of Jethro. Jethro is the famous biblical father-in-law of Moses (who married his daughter Zipporah), an individual mentioned in several biblical passages (e.g. Exodus 3:1; 4:18; and throughout chapter 18). He is also a prominent prophetic figure in the Qur’an, where he is referred to as “Shu’ayb” (or “Shuaib”)—an Arab prophet of God sent to the Midianites, who worshipped a tree (from an archaeological standpoint, sounding rather like an “Asherah pole”—a sacred tree or pole object worshiped by early communities of the Levant). The Midianites’ lack of repentance led to their destruction.

Why the level of devotion to Jethro? The Druze hold themselves to be his very descendants. Their most significant religious site is the traditional site of his tomb—located west of Tiberias, in Israel’s Lower Galilee region, where the patriarch is said to have died in a cave. Pilgrimages to the Nabi Shu’ayb tomb occur annually. The current iteration of the structure, which has undergone multiple renovations throughout history, dates to 1880, with an internal chamber of the structure reportedly dating to as early as the third century c.e. The earliest known description of the shrine dates to 1047 c.e., in the words of the Persian traveler Nasir Khusraw. From the very founding of the State of Israel in 1948, Israel granted the Druze community full custodianship of the site.

“The Druze in Israel revere Jethro and consider him their forefather …. Descendants of Jethro seem to have been divided into two sections: There were those who became completely Jewish …. Others remained separate, led a nomadic type of existence and at times were only loosely associated with Israel. Jael (Yael), who slew the Canaanite military leader Sisera in the story of Barak and Deborah (Judges chapter 4), was the wife of Hebrew the Kenite who would have been a descendant of Jethro” (article, “Are the Druze People Descendants of Jethro, the Father-in-law of Moses?”). Dr. Anan Wahabi highlights the “historical spiritual connection that began with … Jethro and Prophet Shoaib, the spiritual father and prophet of the Druze. Jethro (Moses’s father-in-law) was the Kenite leader that Moshe [Moses] stayed with …. The Druze are descendants of the Kenite tribe” (“The Druze in Israel: Preserving an Ancient and Modern Alliance”).

But wasn’t the biblical—and qur’anic—Jethro/Shu’ayb located in Midian, within the territory to the south of Israel, beyond Edom? Why the connection with the north, and Jethro’s traditional tomb location, so far away? There is an interesting scriptural hint.

Migration North

The biblical Jethro and his kin were Kenites, an Abrahamic tribe of the southern Levant/northern Arabian Peninsula. Through Moses, this friendly tribe became somewhat connected with the Israelite body, though retaining their own identity. There is the account of their delegation visiting the Israelites encamped at Mount Sinai (Exodus 18), and later guiding the Israelites through part of their desert journey (Numbers 10:29-32). The level of favor between the Israelites and Kenites is perhaps best summed up in a message to their community from King Saul, who recalled how they “showed kindness to all the children of Israel, when they came up out of Egypt” (1 Samuel 15:6). Such a close connection to Israel has even led to a certain opinion in scholarship known as the “Kenite Hypothesis”—that the Israelite religion itself was influenced by the Kenites, in part through Moses’s relationship with Jethro. This is, of course, much debated, but the point is made—these were a people closely connected to the Israelites, with familial, political, even a degree of religious connections.

As we highlighted in an earlier article (relating to Rahab), certain of the Kenites traveled with the sojourning Israelites, eventually establishing themselves in the Negev region along the southern border of the tribe of Judah. But one prominent descendant of Jethro elected to travel north and settled in the Galilee region.

“Now Heber the Kenite, a descendant of Moses’ brother-in-law Hobab [son of Jethro], had moved away from the other members of his tribe and pitched his tent by the oak of Zaanannim near Kedesh” (Judges 4:11; New Living Translation; compare with Numbers 10:29). Naturally, there is significant debate about exactly where this territory was located—whether it was in the Upper Galilee (along the border of Lebanon) or the Lower Galilee. Much of the confusion surrounding this passage is based on how to interpret the initial Hebrew letter of the place-name—whether or not it represents the preposition “in” (thus “in Zaanannim,” as in most English translations) or is part of the name itself (thus “Bezaanannim,” as in traditional Jewish translations). Based on additional clues from the early Septuagint translation and the Talmud, several sites have been proposed within the territory just southwest of Tiberias (such as Khirbet Bessum, Hanot Taggarim and Shajarat el-Kalb)—a location of settlement that happens to be in the general vicinity of the Nabi Shu’ayb shrine. (The other name mentioned in the verse, “Kedesh,” signifies a “sanctuary” or “sacred place.”)

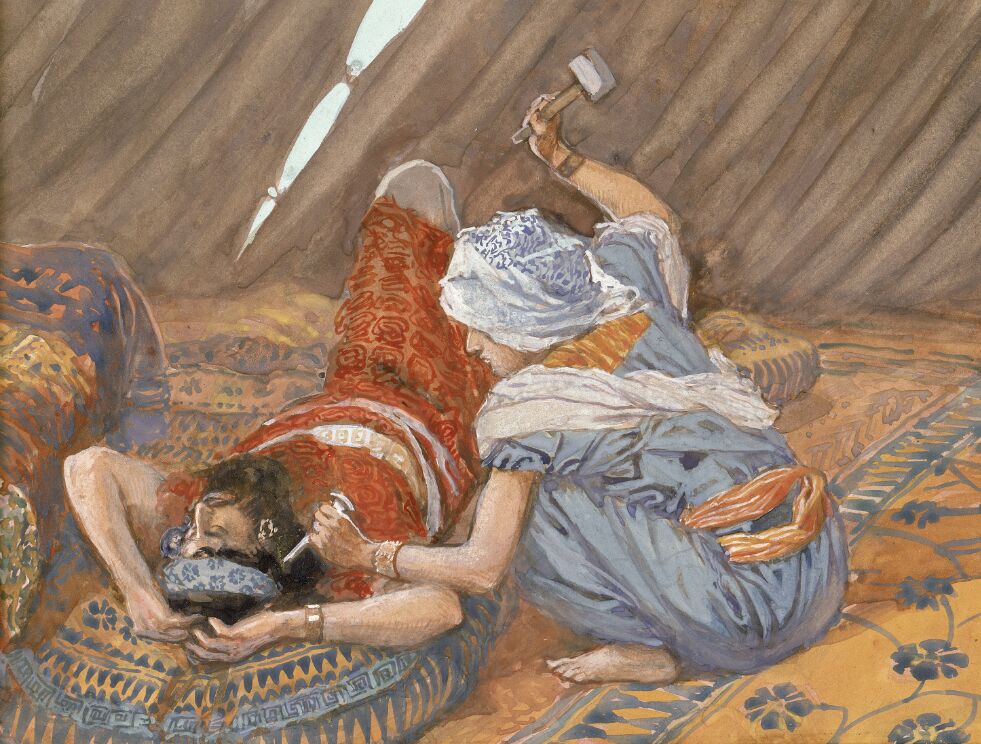

This Judges account introduces the famous oppression of the Israelites by the Canaanite King Jabin and his captain, Sisera. This was an oppression that ended after Sisera, fleeing for his life after a military defeat by the army of Barak and Deborah, sought shelter in “the tent of Jael the wife of Heber the Kenite; for there was peace between Jabin the king of Hazor and the house of Heber the Kenite” (verse 17). After providing Sisera drink and a place to sleep, “Jael Heber’s wife took a tent-pin, and took a hammer in her hand, and went softly unto him, and smote the pin into his temples, and it pierced through into the ground” (verse 21)—ending the reign of terror overseen by Sisera and his forces. (To read more about this account, see our article “Sisera v. Deborah: Evidence of the Biblical Account.”)

The kin of Jethro next reappear in the biblical account during the days of Saul and David (1 Samuel 15:6; 27:10; 30:29), before fading from view.

Kenite-related archaeology from this time period—the Late Bronze Age to the Iron Age—is naturally very piecemeal and comparatively under-studied. Notably, one of the sites associated with this tribe—Horvat Uza (identified with the biblical Kinah)—has a stark absence of the typical anthropomorphic figures found in the region throughout this period. The notable lack of such has been attributed to a remarkable level of “aniconism” in the Kenite community: In the words of Prof. Nadav Na’aman, “the absence of anthropomorphic figurines at the site is exceptional in comparison with other sites all over the kingdom of Judah and may reflect the aniconic tendency of the Kenites” (“The ‘Kenite Hypothesis’ in the Light of the Excavations at Horvat ‛Uza”). Interestingly, one of the key features of the Druze religion is the strict avoidance of iconography.

Also interesting are the results of genetic studies over the past several decades of Middle Eastern and Jewish populations—two studies in particular, which found it “strange that … the Druze, who originated from an Islamic movement at the beginning of the second millennium c.e., were found to be the closest to the Jews,” though no explanation for this was given (Gal Chaimovich, “A Yiddish Genetic,” Hebrew original). The findings were of no surprise to Druze mk (Member of Knesset) Ayoub Kara, speaking of them in 2010: “[W]hen you check our beliefs—and our veneration of the great Jewish prophets—the matter should become clear,” he stated, highlighting his community’s ancient Israelite connections.

3,000 Years Later

It is true that seminal events in the history and development of the Druze religion occurred at the turn of the second millennium c.e. (aptly explained in detail in the video below). As the Times of Israel’s Aviva and Shmuel Bar-Am summarize in their 2018 article “Israel’s Druze Honor the Prophet Jethro in Annual Pilgrimage to Ancient Tomb,” they are generally described as “an offshoot of Islam that differs markedly from Islam in its beliefs,” a movement “established in 1017 by Egyptian ruler Caliph El Hakem bi-amer Allah,” who disappeared under mysterious circumstances in 1021—believed by the community to have been taken into “hiding.” “For the next 26 years [until 1043] people were welcomed into the ranks. After that time, however, the religion was closed to outsiders,” awaiting his return before the Last Judgment.

“Converts are not accepted, and the Druze are forbidden to intermarry. Druze are either religious or nonreligious and only the religious group is allowed to read the holy books and learn its doctrines,” wrote Aviva and Shmuel, noting the community’s esoteric religious nature. Only a basic description of the religion is given to outsiders; even to members of the Druze community who are not of the dedicated religious elite, there is remarkably little understanding about the religion, one in which there is no ritual or ceremonies (besides visitation of the Nabi Shu’ayb shrine—even here, this is not a religious event, although a tradition has developed to do so in late April).

Despite a generally recognized Arab heritage of the Druze, their common Arabic tongue, and what could be described as their closest religious links to Islam, it has been from the Muslim community that the Druze have historically experienced the most persecution—treated as “‘rebels’ who rejected Islamic principles and had to be restored into the fold of Islam” (“The ‘Preservation of the Brethren’ Principle Among Druze Intergenerational Groups in Israel”). Comparatively, relations with the Christian and Jewish communities have been much warmer. This is only solidifying in real time, with events over the past several days.

The Druze community in Israel’s Galilee region have been integrated into Israeli life since the foundation of the state in 1948, with members even participating in the War of Independence. To this day, Druze soldiers serving in the Israel Defense Forces (idf) are renowned as some of the toughest and most dedicated, priding themselves in serving in the most dangerous of frontline roles, and reaching the highest echelons of military leadership.

The Druze community in the Golan Heights (of which Majdal Shams is informally considered the “capital”) has long been more Syria-oriented and comparatively more aloof from Israel—only being territorially incorporated since the 1967 Six-Day War, with the Druze community in the region more closely associated with their Syrian counterparts. Yet the last several years have been witnessing a real turn in their position toward Israel—something that has only accelerated since the events of the Saturday massacre. Dr. Wahabi noted in his aforementioned article, “At the funeral of the 12 children, not a single Syrian flag was raised; it is not even raised in the Druze Mountain in Syria anymore. … The unrest in Syria is bringing the Druze in the Golan Heights closer to the community in Israel. Of the 25,000 Druze in the Golan, thousands have already received Israeli citizenship, and many have begun enlisting in the idf.”

In our press conference with Majdal Shams mayor Dolan Abu Saleh, it was reiterated to us how, though there are still areas of improvement, the life of his community is better under Israeli rule, as compared to the communities in Syria or Lebanon—“there is no comparison.” It was explained that despite the Druze leadership in Lebanon and Syria appearing to side with Hezbollah, these were hollow words said under dictatorial oppression.

To this end, the Druze community is known for a peaceable “loyal[ty] to whichever country they live in,” with “no nationalistic values of their own”—while at the same time “advocat[ing] taqqiya (dissimulation), a practice whereby the Druze conceal their true belief” (Nissim Dana, “Druze Identity, Religion—Tradition and Apostasy”). Dr. Shadi Halabi, Prof. Gabriel Ben-Dor, Prof. Peter Silfen and Dr. Wahabi note the doctrine of “active contribution of Druze to their country of residence while maintaining their own internal values,” with “loyalty to the state … viewed as a theological value” (“The ‘Preservation of the Brethren’ Principle Among Druze Intergenerational Groups in Israel”). Even this brings to mind Heber the Kenite, for whom during Canaanite control of the northern regions “there was peace between Jabin the king of Hazor and the house of Heber” (Judges 4:17)—peace, that is, right up until Jabin’s oppressive Sisera-led forces were defeated.

For the Druze in Israel, however—particularly those in the Galilee—there has been remarkable enthusiasm for service. Israeli Lt. Col. (res.) Gideon Harari, speaking alongside the Majdal Shams mayor on Tuesday, emphasized repeatedly what he called a “covenant” relationship between the Jewish community and the Druze—a relationship that, more than 3,000 years on, Jethro—Shu’ayb—would still recognize among his children.