The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World—the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Statue of Zeus, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Temple of Artemis, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon—have captured imaginations for thousands of years. The Great Pyramid of Giza still awe-inspires to this day. And while none of the other wonders are still standing, their influence (like how the Statue of Zeus inspired the Lincoln Memorial statue) lives on to the modern day.

But as far as the ancient world is concerned, most of these wonders are at the epoch’s tail end. Most of them were constructed by the Greeks, hundreds of years after Egypt’s native pharaohs and the kings of Babylon, Assyria and Israel had come and gone. What did the people who lived before the building of the Colossus and the Lighthouse consider “wonders of the world”? The ancient world certainly has left us many other impressive structures—like the temples of Luxor and Karnak in Egypt, England’s Stonehenge and Persepolis in Iran.

There was one similarly grand structure that is no longer standing. Its history may not be as common knowledge as some of the other buildings. But its builder was so impressed with the final product that he called it “a wonder for all peoples.” Its splendor may have been so renowned as to find its way into the Bible. And it may have influenced our list of the ancient wonders today—and it may have even been one of them. This wonder is a “hanging garden”—not in Babylon, but in the Assyrian capital of Nineveh. Its maker was one of the Bible’s most infamous conquerors: Sennacherib, king of Assyria.

Nineveh’s Wonder

Sennacherib’s reign is generally dated to 705–681 b.c.e. His father, Sargon ii, started his dynasty in 721 b.c.e. (The Bible references Sargon directly in Isaiah 20:1, and Assyrian records reveal him as the king responsible for the final defeat and uprooting of the northern Israelite tribes, as recorded in 2 Kings 17.) After Sargon died, Sennacherib moved Assyria’s capital from Dur-Sharrukin to Nineveh.

Famously, Sennacherib initiated an attempt to conquer Judah. Yet despite notable victories, including at Lachish (often referred to as Judah’s “second city”), Sennacherib was unable to conquer Jerusalem. The Bible describes God miraculously snuffing out Sennacherib’s offensive (2 Kings 18-19; Isaiah 36-37; 2 Chronicles 32). It is one of very few stories to receive so much attention in so many biblical books. (See here for archaeological corroboration of Sennacherib’s war with Judah.) Defeated, Sennacherib returned to Nineveh. But what did he do when he returned? Isaiah 37:37 states: “So Sennacherib king of Assyria departed [from Judah], and went, and returned, and dwelt at Nineveh.” The word “dwelt,” according to Gesenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon, can mean “to sit down” or “to remain.”

It is in this time frame that Sennacherib began constructing what archaeologists call Nineveh’s Southwest Palace. But Assyrians at the time called it “the Unrivaled Palace” or “the Incomparable Palace.” British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard excavated the Southwest Palace in 1847 and later from 1849–1851.

Much of the palace today is still unexcavated, and much of what has been found is in ruins. But these ruins are enough to give a sense of how grand the structure would have been in its heyday. The palace had an estimated length of nearly 500 meters (over 1500 feet) and was roughly 242 meters (726 feet) wide. The walls were up to 7 meters (21 feet) thick. Massive lamassu—stone sphinx-like creatures—guarded the entrances. Sculptured panels, including the famed Lachish reliefs illustrating Sennacherib’s conquest of Judah, decorated the interior.

Especially notable were the gardens. Being built on a hill, the palace was already high, at 24 meters (72 feet) above ground level. But for the gardens, he further altered the terrain, creating artificial heights in imitation of the Amanus Mountains in southern Turkey. He describes his palace and garden in a prism, now in the British Museum. The text of the prism reads:

In order to draw water up all day long, I had ropes, bronze wire and bronze chains made. And instead of a shaduf [an ancient method for raising water] I set up the cylinders and screws of copper over cisterns. I made those pavilions look just right. I raised the height of the surroundings of the palace, to be a wonder for all peoples. I gave it the name ‘Incomparable Palace.’ A high garden imitating the Amanus Mountains I laid out next to it, with all kinds of aromatic plants, orchard fruit trees, trees that enrich not only mountain country but also Chaldea [Babylonia], as well as trees that bear wool, planted within it.

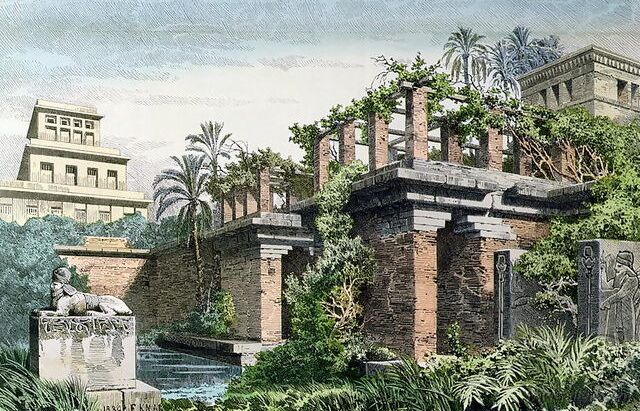

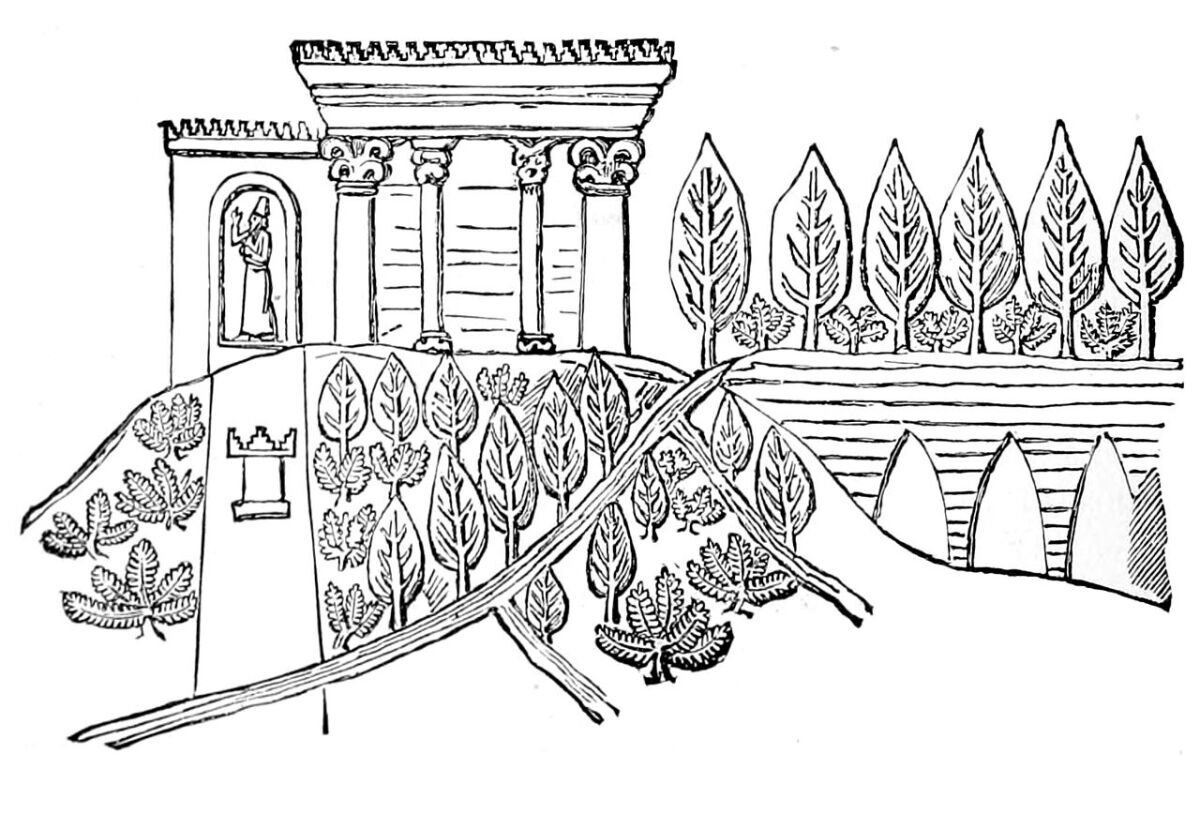

Wall reliefs from the Southwest Palace depict massive gardens of trees sloping upward against mountains. The original reliefs have since been lost, but archaeologists fortunately made drawings that still exist. Many identify these depicted gardens with those of the Southwest Palace. One panel shows an aqueduct pouring water down a mountain, watering trees of unique types. The depicted garden has ornate architectural features, including a colonnade and two towers. Another shows a lake next to the garden big enough for people to row boats in.

Sennacherib had an ingenious method of sustaining this hilltop garden. As his annals describe, he instituted a system of Archimedes’ screws, cast of copper, to water the garden (hundreds of years before the Greek scientist would lend his name to them). In addition, to supply the water for this and other gardens, Sennacherib built an elaborate system of canals at Nineveh. Sennacherib commissioned at least four canals to bring water into his city, as well as a dam and an aqueduct.

References in the Bible?

Sennacherib may have overseen the construction of one of the greatest botanical marvels in the world—but he was also a bloody tyrant. This is borne out in his own graphic descriptions of his conquests, as well as the Bible. Probably the most graphic example of this is found in the book of Nahum. The Prophet Nahum penned a curse on Nineveh sometime in the second half of the seventh century b.c.e. (This is dated from his prophecy predating Babylon’s sack of Nineveh in 612 b.c.e., but referencing the 663 b.c.e. Assyrian sacking of Egypt’s capital Thebes, also known as No-amon, in Nahum 3:8.)

In his prophecy, Nahum references the splendor and wealth of seventh-century Nineveh. “Take ye the spoil of silver,” Nahum writes to Nineveh’s marauders, “take the spoil of gold; For there is no end of the store, Rich with all precious vessels” (Nahum 2:10 JPS). Nahum also makes an interesting comment in verse 9: “But Nineveh hath been from of old like a pool of water.” Strong’s Concordance renders this word “pool” as meaning “reservoir.” The Bible uses the same word in 2 Samuel 2:13 to describe a manmade cistern in Gibeon (since uncovered by archaeologists). Nehemiah 3:15 likewise refers to a pool in Jerusalem “by the king’s garden,” plausibly to water it. The same word also refers to the “lower pool” and the “old pool” of Isaiah 22:9-11, referring to King Hezekiah’s renovation of Jerusalem’s preexisting subterranean water network.

The “pool” in Nahum 2:9 evidently refers to artificial waterworks. In at least one instance, this word is used in association with gardens. And according to Nahum, this “pool” can be a metaphor for Nineveh as a whole. Could this be referring to Sennacherib’s elaborate system of waterworks, culminating in his grand garden, part of his “wonder for all peoples”?

This isn’t the only possible reference in the Bible to Sennacherib’s gardens. The Prophet Ezekiel penned his book in the early sixth century b.c.e., while in Babylonian captivity. By this point, Assyria was long gone as a world power. But in Ezekiel 31, the prophet uses an interesting metaphor to describe the Assyrian empire that once was: “Behold, the Assyrian was a cedar in Lebanon, With fair branches, and with a shadowing shroud, And of a high stature; And its top was among the thick boughs. The waters nourished it, The deep made it to grow; Her rivers ran round About her plantation, And she sent out her conduits Unto all the trees of the field. Therefore its stature was exalted Above all the trees of the field; And its boughs were multiplied, And its branches became long, Because of the multitude of waters, when it shot them forth. … Nor was any tree in the garden of God Like unto it in its beauty” (verses 3-5, 8).

Ezekiel’s description would aptly describe Sennacherib’s “unrivaled” garden city, built on a tall hill, sustained by a vast artificial watering system.

The Hanging Gardens—of Nineveh?

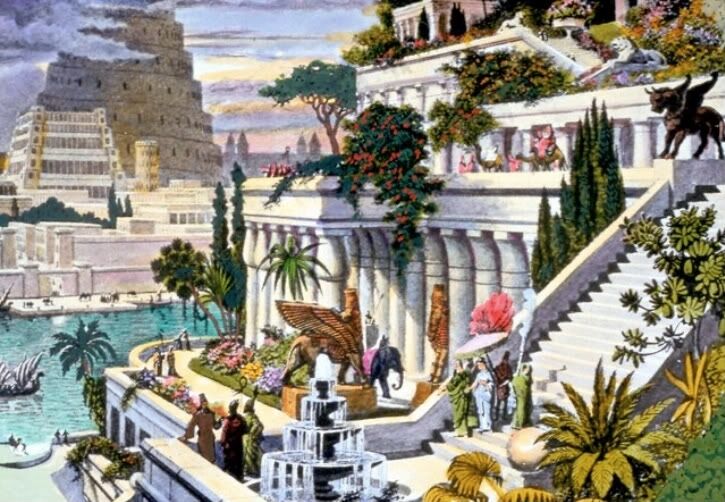

Sennacherib’s garden is ancient history, but it may still live in the public memory, and in an especially unusual way. Of all the ancient seven wonders, the most mysterious is the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Greek and Roman writers make mention of their existence. The Jewish historian Josephus labels them the brainchild of Nebuchadnezzar. But over the course of more than a century of excavations at Babylon, not a shred of archaeological evidence has surfaced confirming their existence. Not only are there no structural remains corresponding to the classical descriptions, but not even a single Babylonian inscription uncovered mentions them. Nebuchadnezzar was a noted builder—his impressive Ishtar Gate, displayed in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, show the grandiose building scale to which he redeveloped Babylon. He was also a braggart; the individual bricks in his buildings often have his name stamped on them. Yet there is no evidence in Babylon itself for his fabled Hanging Gardens.

University of Oxford Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley believes that the Hanging Gardens of the classical accounts weren’t actually in Babylon, but are instead a description of Sennacherib’s gardens in Nineveh. Her book The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: An Elusive World Wonder Traced compares the archaeological evidence of Sennacherib’s gardens with the classical accounts, highlighting the following:

- Josephus and Diodorus (a Greek historian of the first century b.c.e.) state that the structure was built in imitation of a mountainous forest. The standard Babylonian style of garden was flat and based around irrigation ditches. The Assyrians, by contrast, built their gardens on artificial hills and with alpine foliage purposely to imitate a mountain landscape. Ashurnasirpal ii and Sargon ii constructed similar gardens. Sennacherib specifically mentioned that his garden was meant to look like a mountain range.

- Philo of Byzantium (who wrote between the third and fourth centuries c.e.) and Strabo (first century b.c.e.) mention aqueducts and Archimedes’ screws in relation to the garden, matching the description in Sennacherib’s prism.

- Diodorus and Quintus Curtius Rufus (a Roman writer in the first century c.e.) claim that a Syrian king built the gardens, contradicting Josephus. A bilingual inscription (Phoenician and Luwian) from southern Turkey dated to the eighth century b.c.e. uses the word “Syrian” and “Assyrian” interchangeably, suggesting the two words could have been synonymous with each other in ancient times. And Assyria was geographically more proximate to Syria than Babylon.

- Wall reliefs from Nineveh portray Assyrian gardens as an area to listen to music and watch athletic competitions. This may relate to Diodorus’s claim that the Hanging Gardens looked like a Greek theater.

- Diodorus and Josephus claim the king built the Hanging Gardens as a gift for his queen. Sennacherib apparently had a very happy marriage with his first wife, Tashmetu-Sharrat, and dedicated part of the Southwest Palace to her.

In concert with Dalley’s conclusions, there is a growing audience that now believes the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were actually in Nineveh all along. She makes as solid a case as anybody could with the evidence available. Still, Babylon and Nineveh were both well-known cities in the Greco-Roman world, and it would seem remarkable that so many authors would confuse the two. (It would be analogous to multiple authors writing over the span of several centuries claiming the Colosseum is in Paris when they really meant Rome.) For her part, Dalley’s explanation is that a confusion of names may have stemmed from Sennacherib’s desire to build Nineveh as a “new Babylon,” with this association sticking after his death. (Continuing our analogy, Napoleon tried to remodel Paris as a “new Rome.”)

So, are Sennacherib’s gardens the real hanging gardens of ancient lore? The jury is still out.

But one thing is for certain: Sennacherib’s gardens were an engineering marvel—one that is almost certainly described to some degree in the biblical account—and a true wonder of the world: a “wonder for all peoples.”