The Queen of Sheba’s visit with King Solomon in Jerusalem is one of the most vivid scenes in the Bible. The Bible says that when Sheba heard about Solomon’s wealth and wisdom, she was skeptical and traveled to Jerusalem to “prove him with hard questions.”

The queen and her entourage carried many gifts with them, including gold, precious stones and “camels that bare spices” (1 Kings 10:2). The queen was so impacted by her time with Israel’s king and was so moved by Solomon’s unrivaled wealth, culture and education, that she felt compelled to pay tribute to him. Verse 10 indicates that Sheba’s main item of trade was spices, and that “there came no more such abundance of spices as these which the queen of Sheba gave to king Solomon.”

Prior to 2023, there was no archaeological evidence attesting to the biblical Queen of Sheba’s visit to Jerusalem or to a spice trade between Arabia and the kingdom of Israel. But this changed with the reanalysis of the enigmatic Ophel Pithos Inscription, conducted by expert epigrapher Dr. Daniel Vainstub.

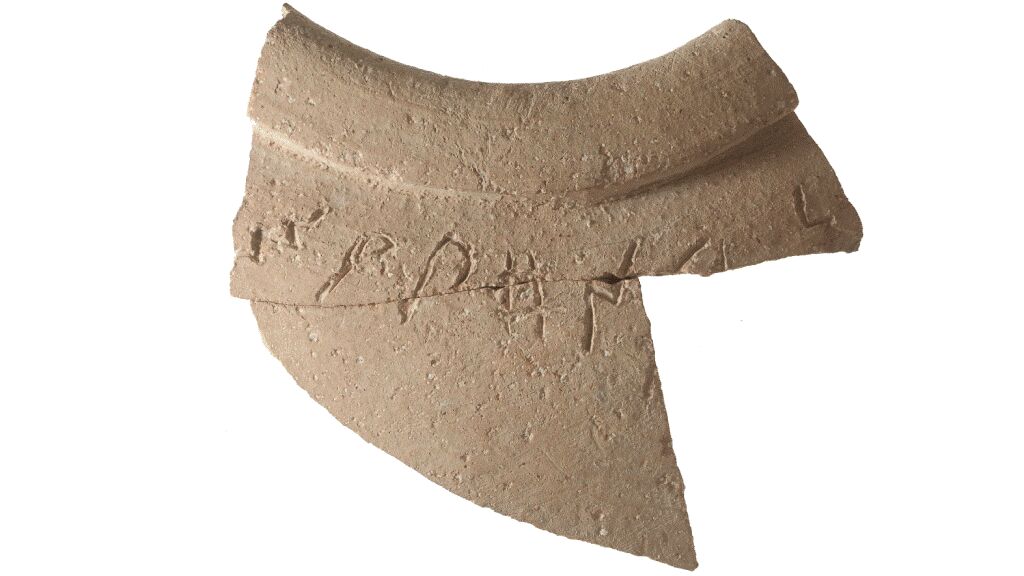

The Ophel Pithos Inscription was first discovered by Dr. Eilat Mazar in late 2012. The clay artifact was found in the southeast corner of the Ophel. It was discovered among a number of large, broken pithoi (storage vessels) pieces embedded in a void in the bedrock. Dr. Mazar and her team were stunned to discover that one of the sherds—part of the rim of one of the vessels—contained a comparatively large inscription, one that was easily noticeable to the human eye.

Given the dating to the 10th century b.c.e.—a dating corroborated in 2020 in a meticulous stratigraphic and ceramic analysis published by Dr. Ariel Winderbaum—the discovery was hailed as the earliest alphabetical inscription ever found in Jerusalem and among the earliest found in Israel.

But what did the inscription say? What language was it written in? These questions remained unanswered.

Scientists accepted that it represented a Semitic language. The prevailing view was that it was a proto-Canaanite inscription, with some arguing for its identification more specifically as a Hebrew inscription. But given the fragmentary nature of the inscription, there was no consensus as to what it said (theories were floated that it may contain the word for “wine”).

In April 2023, in an article published in Hebrew University’s Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology, Dr. Vainstub presented an entirely different conclusion: that the inscription is actually Ancient South Arabian (asa). Furthermore, Dr. Vainstub concluded that the inscription refers particularly to the trade of incense known as ladanum (Cistus ladaniferus) from the southern Arabian Peninsula.

This conclusion brings together a remarkable convergence of biblical information. The territory of Sheba is widely identified by scholars with the southwestern tip of the Arabian Peninsula, in the area of modern-day Yemen. The 10th-century dating fits with the biblical chronology of the time period for the Queen of Sheba’s visit to King Solomon’s Jerusalem and its temple (not far, we might add, from the findspot location). The biblical account describes her bringing a “very great train, with camels that bore spices.”

The Ophel inscription provides archaeological and textual evidence of the trade of spices between the Arabian Peninsula and Jerusalem!

A press release issued by Hebrew University stated: “According to the new interpretation, the inscription on the jar reads, ‘[ ]shy l’dn 5,’ meaning five ‘šǝḥēlet,’ referring to one of the four ingredients mentioned in the Bible (Exodus 30:34) required for the incense mixture. The ‘šǝḥēlet’ was an essential ingredient in the incense that was burnt in the first and second temples …. This indicates a clear connection between Jerusalem of the 10th century b.c.e. (the days of the kingdom of Solomon) and the kingdom of Sheba.”

“Apart from the š, which has a minor anomaly, all the surviving letters of the inscription display the stance and characteristic features of Phase A of asa script,” Dr. Vainstub wrote. This is in contrast to the problematic letters in identifying the script as proto-Canaanite or Hebrew.

Intriguingly, one enigmatic letter on the inscription that posed a real difficulty in interpretation—“its remains do not fit the shape of any Canaanite letter”—is nicely paralleled in the Ancient South Arabian script. He believes that this pithos inscription represents evidence of this kind of biblically attested 10th-century trade between southern Arabia and Jerusalem (a distance of over 2,000 kilometers, or 1,240 miles).

Even the interpretation of the letter representing a quantity of “five” in South Arabian form would be a good fit. Pithoi of this type had a capacity of roughly 110-120 liters (26-32 gallons). The ephah, a common measure in the Bible, equates to about 20-24 liters (5-6 gallons). Therefore, the storage vessel would have logically been able to contain precisely this numeric quantity of product—five ephahs.

As summarized in the press release, during the 10th century b.c.e., the kingdom of Sheba “thrived as a result of the cultivation and marketing of perfume and incense plants, with Ma’rib as its capital. They developed advanced irrigation methods for the fields growing the plants used to make perfumes and incense. Their language was a South Semitic one. King Solomon is described in the Bible as controlling the trade routes in the Negev, which Sabaean camel caravans carrying perfumes and incense plants passed through on their way to Mediterranean ports for export.”

“It appears that the pottery jar was produced around Jerusalem and the inscription on it was engraved before it was sent for firing by a speaker of Sabaean who was involved in supplying the incense spices,” the press release continued. Dr. Vainstub believes that the inscription was engraved by a native speaker of the southern Arabian language stationed in Jerusalem and involved in supplying the incense spices.

He summarized: “Deciphering the inscription on this jar teaches us not only about the presence of a speaker of Sabaean in Israel during the time of King Solomon, but also about the geopolitical relations … in our region at that time—especially in light of the place where the jar was discovered, an area known for also being the administrative center during the days of King Solomon. This is another testament to the extensive trade and cultural ties that existed between Israel under King Solomon and the kingdom of Sheba.”

He further noted the until-recently limited amount of research into the Ancient South Arabian script—a field that has “expanded enormously in recent decades,” thus allowing for the identification of this inscription as an example of such.

Dr. Vainstub concluded his research article: “The discovery of the Ophel inscription marks a turning point in many fields. Not only is this the first time an asa inscription dated to the 10th century b.c.e. has been found in such a northern location, but it is also a locally engraved inscription, attesting to the presence of a Sabaean functionary entrusted with incense aromatics in Jerusalem.

“The Ophel inscription makes an important contribution to the age-old question of the likelihood of a visit by a delegation from the South Arabian Peninsula to King Solomon in the 10th century b.c.e. as related in 1 Kings 10 and 2 Chronicles 9 …. Our inscription marks the starting point of what was to be a lengthy supply line of aromatics from Sheba to the temple of Jerusalem, as expressed by two prophets [Isaiah and Jeremiah]. Thus, in Isaiah (60:6; Alter) it is said that ‘a tide of camels shall cover you, dromedaries from Midian and Ephah, they shall come from Sheba. Gold and frankincense they shall bear and the Lord’s praise they shall proclaim.’”

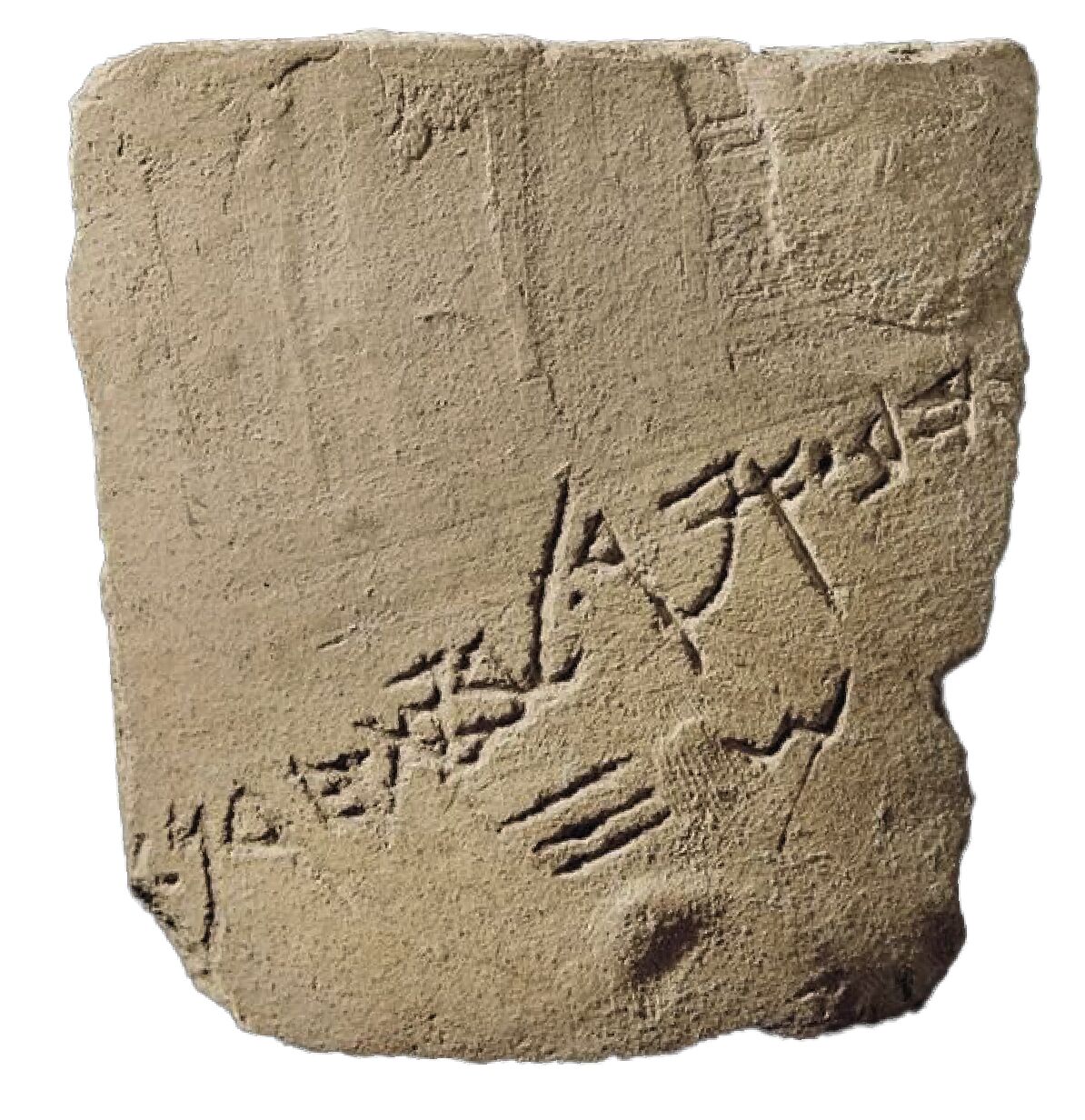

Sidebar: Legendary ‘Gold of Ophir’—Not Just Legend

The Bible records that kings Solomon and Hiram collaborated on establishing Israel’s navy. 1 Kings 9:26-28 state that Solomon enlisted Hiram to set up a navy at Ezion-geber, an ancient port on the Red Sea (near the modern city of Eilat). From that port, the Israelite-Phoenician navy undertook missions sailing to the land of Ophir, famed for its gold reserves.

The Bible says that Solomon acquired 420 talents of gold from Ophir—some estimates put that at $1.6 billion in today’s value. The incredible amount of gold that Solomon acquired from this site led many to consider it just legend.

Yet evidence points to the fact that this location—and its abundance of gold—existed.

An ostracon found during the 1946 archaeological excavations of Tell Qasile (a site in Tel Aviv) validates the existence of Ophir and its connection to gold. The inscription reads: “Ophir gold to Bet Horon: 30 shekels.”

While this ostracon and the settlement it was discovered in date to the eighth century b.c.e., this discovery confirms the veracity of the Bible in its reference to Ophir as a source of gold in the ancient world.