The Psalms repeatedly refer to the gates of Jerusalem, some of the most prominent symbols of the holy city. Reading these passages, it is easy to picture the Jaffa Gate or the Damascus Gate in the Old City. But these are not the gates the psalmists referenced. They were speaking of the gates of the original city conquered by King David and significantly developed by Solomon, Hezekiah and Josiah.

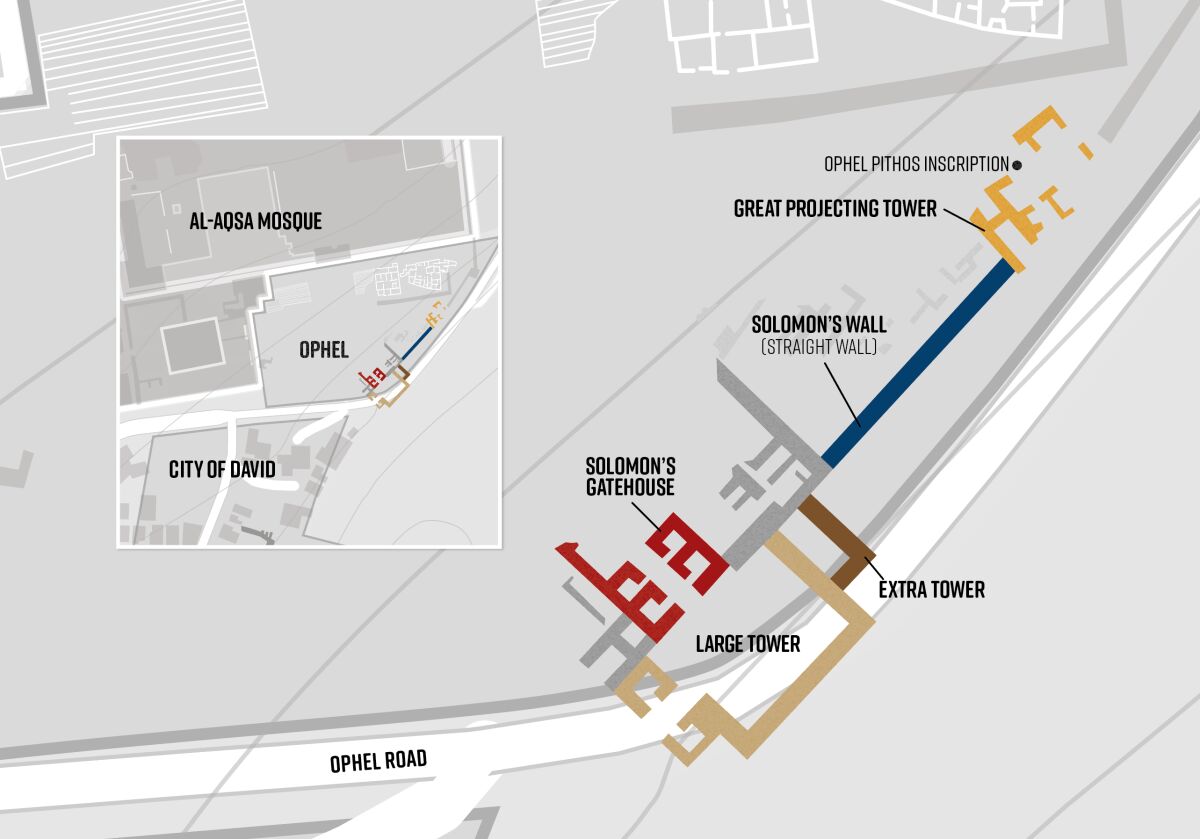

We actually know the precise location of one of these ancient gates, as well as its associated straight wall and projecting tower. Analyzing the archaeology of all three features provides an impressive snapshot of King Solomon’s monumental building program in Jerusalem.

The Wall

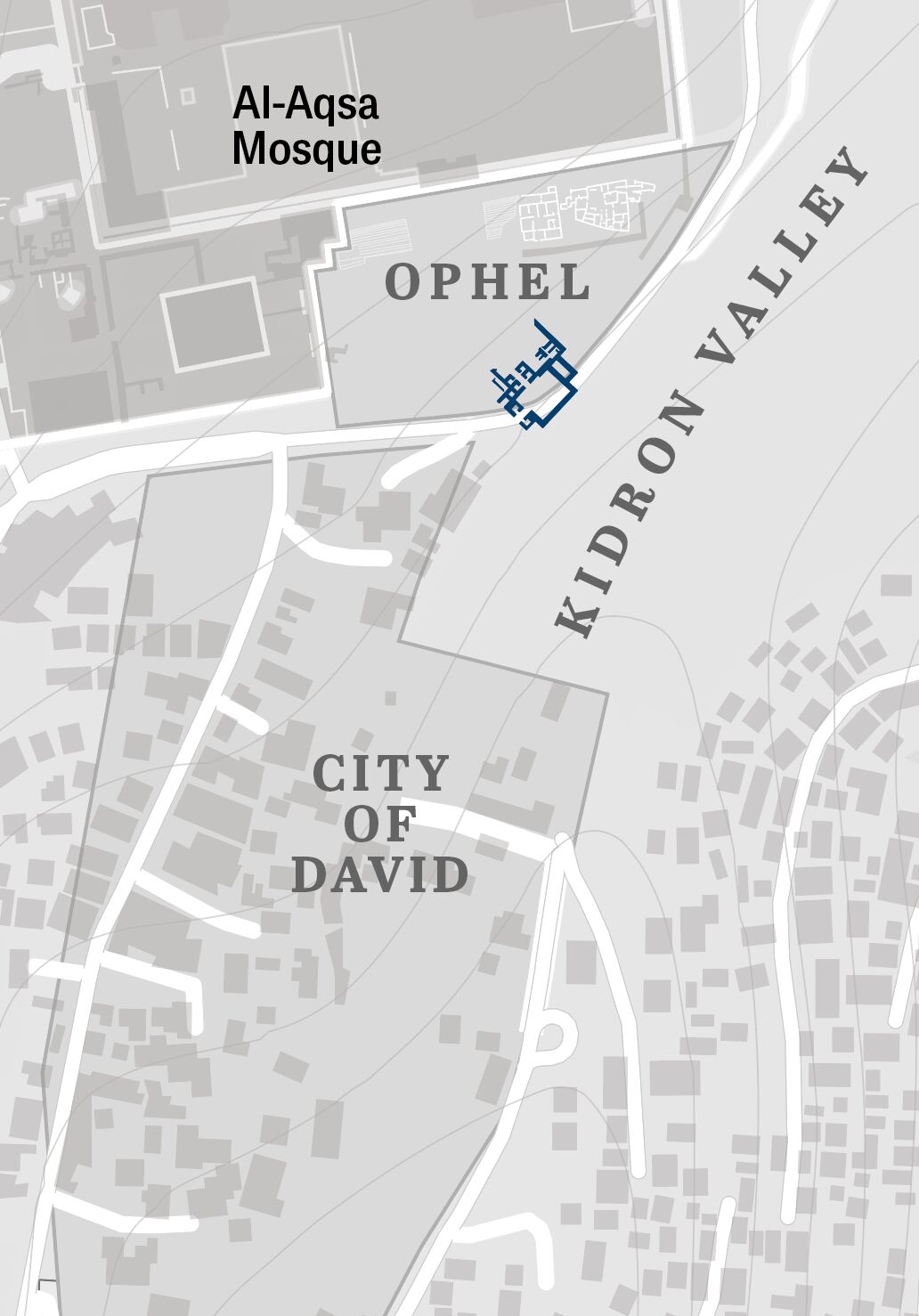

“The Lord loveth the gates of Zion More than all the dwellings of Jacob” (Psalm 87:2). The psalmist believed God took special interest in the gates of ancient Jerusalem, which were located on Zion. Zion in the Bible refers to a long, crescent-shaped north-south ridge bordered on the east by the Kidron Valley and on the west by the Tyropaeon Valley.

During the time of Abraham, when Jerusalem (then called Salem) was first established, settlement was located at the southern end of this ridge, centered around the Gihon Spring. This settlement still existed in the same location six centuries later when Israel conquered the Promised Land under Joshua. It was then inhabited by Jebusites and called Jebus.

About 400 years later, around 1000 b.c.e., King David and his army laid siege on Jebus and took the city. “Nevertheless David took the stronghold of Zion; the same is the city of David” (2 Samuel 5:7). From this time on, the Bible generally refers to the most southern, most ancient part of Jerusalem as the City of David.

Both archaeology and the biblical record show that David fortified the existing, relatively small city of Jerusalem on the Zion ridge. His greatest building project was the new royal quarters north of this city, as evidenced by excavations undertaken by Dr. Eilat Mazar.

When King David died, the kingdom of Israel was powerful, secure and prosperous. This allowed his successor, Solomon, to undertake massive construction projects in Jerusalem and across the kingdom.

“And Solomon became allied to Pharaoh king of Egypt by marriage, and took Pharaoh’s daughter, and brought her into the city of David, until he had made an end of building his own house, and the house of the Lord, and the wall of Jerusalem round about. … And this is the account of the levy which king Solomon raised; to build the house of the Lord, and his own house, and Millo, and the wall of Jerusalem, and Hazor, and Megiddo, and Gezer” (1 Kings 3:1; 9:15).

“The house of the Lord,” the spectacular temple at Jerusalem, became world famous. But notice that in addition to building the temple, his own palace and numerous fortified cities, Solomon built “the wall of Jerusalem.” If it was anything like the palace and the temple, it would have been an impressive structure.

The palace, the temple and the wall were part of Jerusalem and therefore built on the Zion ridge. Where? The geography of Jerusalem reveals the answer. Deep valleys to the south, east and west of the city would have logically forced new development further north.

The Bible refers to this part of Jerusalem’s topography as the Ophel. The meaning of this word is somewhat obscure, but it can be defined as a swelling or raised mound. The Bible and geography indicate that this northward expansion is where Solomon built the temple, his palace and “the wall of Jerusalem.”

What does archaeology tell us?

In 2010, excavations performed by Dr. Mazar on the Ophel, sponsored by Daniel Mintz and Meredith Berkman, uncovered a 34-meter-long (112 feet), 2.5-meter-wide (8 feet) portion of a massive wall. This wall was dated to the 10th century b.c.e. Up until this excavation, it was believed that this extra length of city wall, also known as the “straight wall,” was built after Solomon (by possibly 200 years). However, by excavating the stratified layers against the base of the wall, Dr. Mazar’s team learned that this city wall was built during the 10th century.

The Jerusalem Gatehouse

The relatively recent discovery of Solomon’s large wall complements another massive structure, one that began to be excavated decades earlier: the Ophel City Gate. While the Bible records that Jerusalem had many gates, the Ophel City Gate is the only thus far discovered and securely dated to the First Temple Period.

Several gates from the biblical period have been found in Israel. As previously mentioned, gatehouses have been excavated in Hazor, Megiddo, Gezer—cities listed as part of Solomon’s building program (1 Kings 9:15). The gatehouses in these cities are massive, with six chambers each. Others discovered have four.

When comparing the Ophel Gate in Jerusalem with the Palace Gate at Megiddo, Dr. Mazar noted that the lengths, width of the central passages, thicknesses of the walls, and sizes of the chambers are virtually identical. This “seem[s] to indicate that the two gatehouses were built according to an identical blueprint, most likely originating from the same architectural office,” she wrote (Discovering the Solomonic Wall in Jerusalem).

The dating of the Ophel gatehouse, however, has come under debate by other scholars, especially since Dr. Mazar’s death in 2021.

Two academic papers published in the Tel Aviv archaeological journal have attempted to redate Dr. Mazar’s Ophel gatehouse out of the 10th century. The first, “The Iron Age Complex in the Ophel, Jerusalem: A Critical Analysis,” was written by Prof. Israel Finkelstein. It posits that the entire gatehouse structure was constructed in the eighth century or later.

The second paper, “Jerusalem’s Growth in Light of Excavations of the Ophel,” was written by Dr. Ariel Winderbaum, who recently completed his Ph.D. dissertation on the pottery assemblage of Dr. Mazar’s Ophel excavation. Winderbaum believes that while the foundation of the Ophel gatehouse does belong in the 10th century, the upper gatehouse should be dated to the eighth.

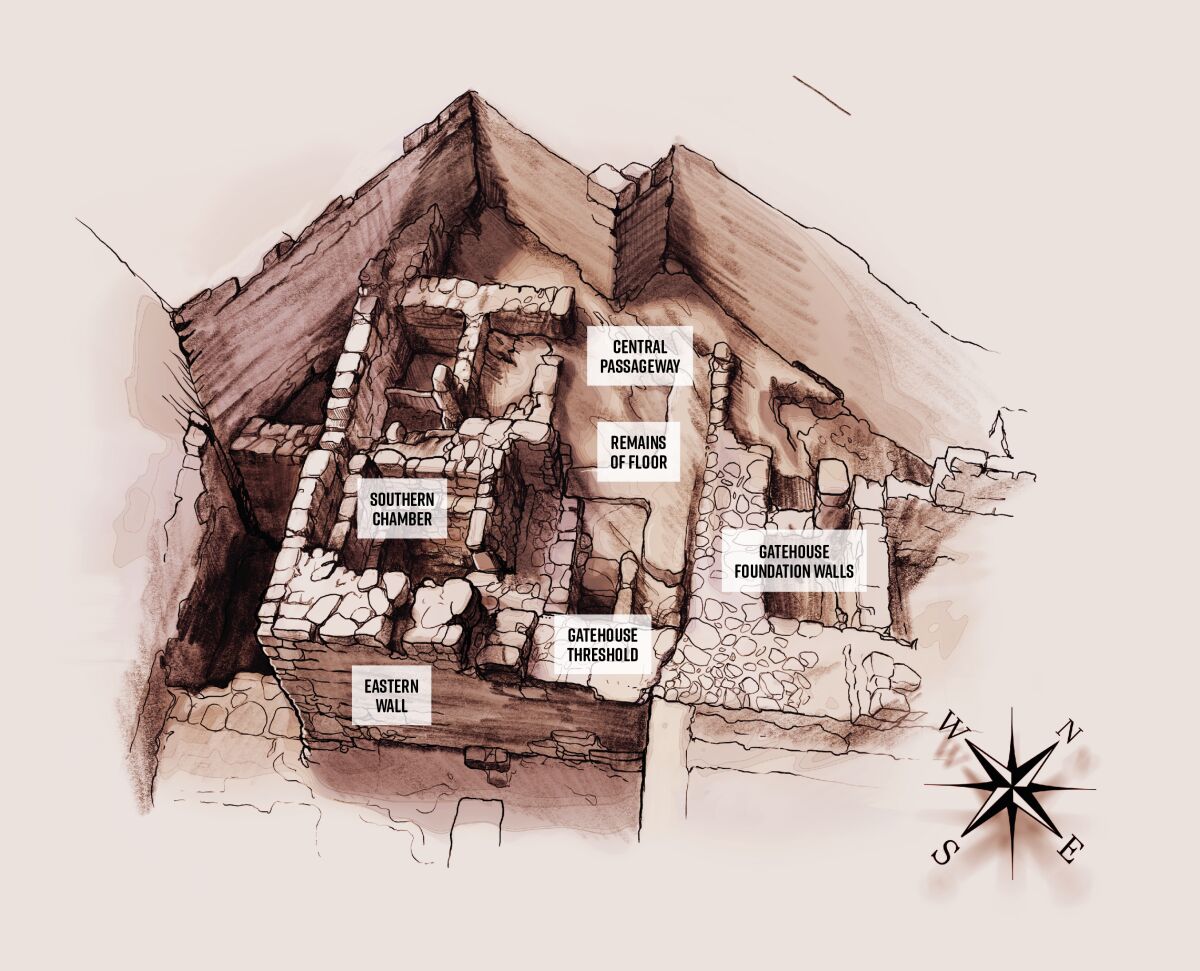

Obviously, both of these views conflict with Mazar’s dating of the entire gatehouse to the 10th century b.c.e. Can her dating be defended? To understand why she dated the entire gatehouse to the 10th century, we must examine three distinct features: the eastern wall, the central passageway and the southeastern chamber.

First, it’s important to note: Mazar found what is indisputably 10th-century pottery in all three areas. The Bible relates that King Solomon reigned in Jerusalem for 40 years, during which Jerusalem experienced development and significant population growth. This means that the 10th-century pottery Dr. Mazar found is most likely associated with Solomon.

Any attempt to redate the Ophel gatehouse out of the 10th century must explain the presence of 10th-century pottery in a gatehouse they claim was built much later.

Let’s examine each of the three sections of the Ophel gatehouse.

The Eastern Wall

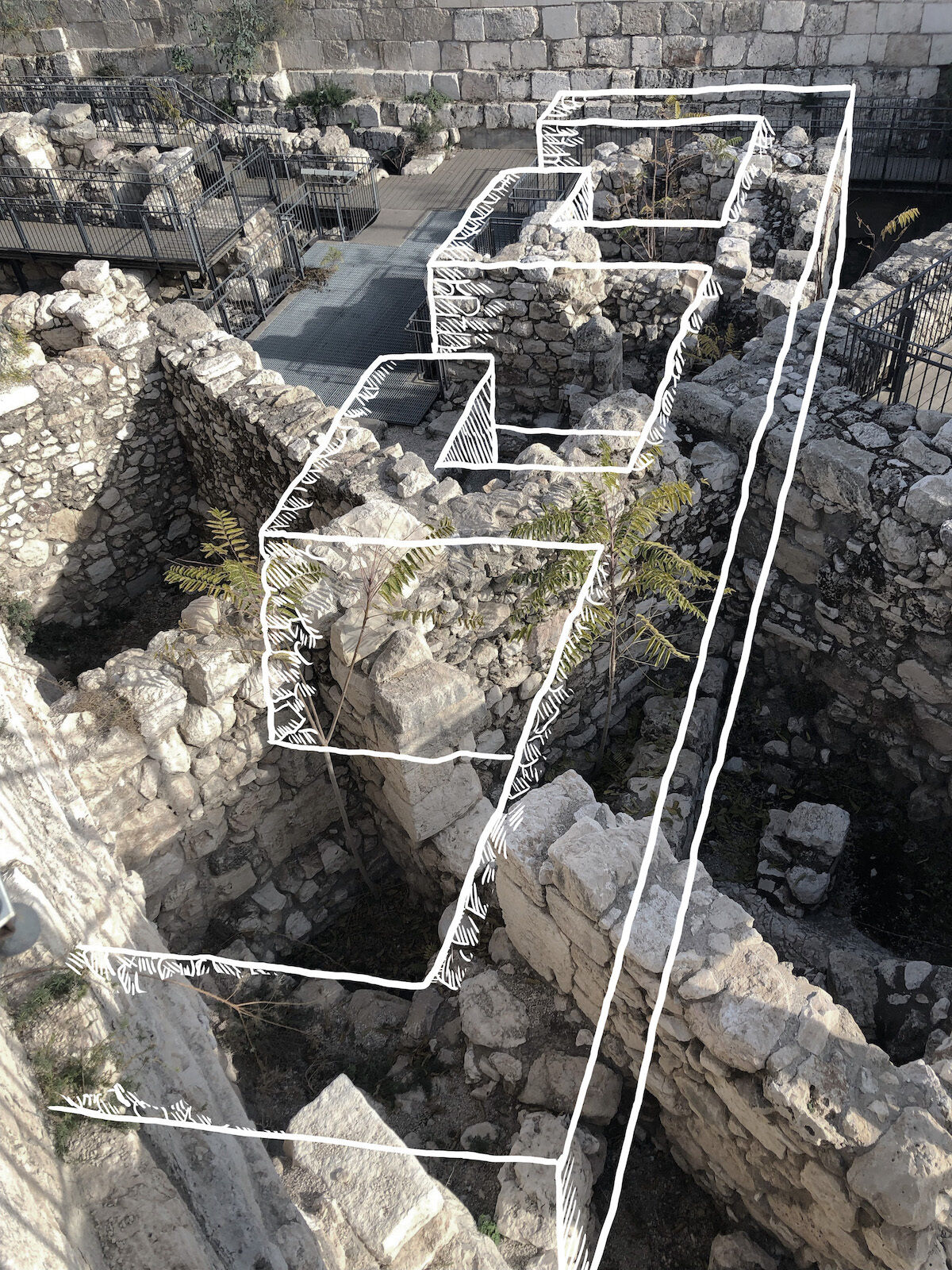

The full extent of the huge eastern wall was uncovered in the 2009–10 excavation. Though there are some slight variations in the wall’s construction style—for example, a correctional course of stones about halfway up the wall—its look and design are generally consistent from top to bottom. Like all First Temple Period walls in the Ophel, the eastern wall is built directly on bedrock.

After the construction of the eastern wall, a massive earth fill was brought in to raise the floor level to the same height as the gatehouse entrance. The pottery found in the lower portion of this fill was dated to the time of Solomon. Using this pottery, Dr. Mazar dated the eastern wall to the same period.

A separate 4-meter-high (13 feet) wall abuts the north end of the eastern wall. This wall is the same height as the gatehouse entrance. Dr. Mazar interpreted this to be a wall that was built to hold the earth fill in place inside the projecting tower that protected the entrance to the gate. The fact that this supporting wall reaches the same height as the eastern wall at the gate entrance is additional proof this was a walkway.

Both Winderbaum and Mazar showed that the pottery found in the lowest fills against the eastern wall clearly dates to the Solomonic period. Winderbaum believes the eastern wall’s lowest courses were built separately (and earlier) from the upper courses of the gatehouse. Dr. Mazar disagreed; she believed the entire eastern wall was one unit and was constructed at the same time. The reason Winderbaum believes the upper wall was built later is that pottery sherds in the upper parts of the fill dated to the later period.

But this doesn’t mean the upper wall had to be built separately. The presence of later-period pottery in the upper level isn’t unexpected; it was likely imported with fill that would have been occasionally brought in to raise the floor (which wore down over time). Importantly, the lowest levels of the fill did not produce any late pottery. Winderbaum also believes the correctional course halfway up the wall is another indication it is a later addition.

Finkelstein’s view is different still. He wrote, “If the latest sherds in this fill indeed date to the Iron iia, they are in contrast to the lowest fill below the gatehouse.” This does not address the issue, but perhaps it is a slight admission that the fill against the wall belongs to the Solomonic period.

While he concedes the presence of Solomonic-period pottery, Finkelstein has a plausible, though creative, suggestion for how it might have found its way into the fill. “Indeed, the earth for the fill could have been brought here at a later phase of the Iron age from a dump-debris with Iron iia sherds.” While possible, the sheer mass of Solomonic sherds without a single later sherd makes this extremely unlikely. Furthermore, if as Finkelstein believes, Jerusalem was a mere tribal village at this time, how far away did the builders have to travel to find fill that contained so much Solomonic-period pottery?

The Gatehouse Passageway

Excavation of the central passageway of the gatehouse has a long history. In the final two days of excavation in 1986, Dr. Mazar examined a cross-section of the passageway situated underneath an early-Roman-period wall. In her sample dig, she found a “wonderfully preserved lime floor” with pottery sitting on top. The following season (summer 1987), Mazar and her team dismantled the later structures, fully exposing the lime floor. The limestone passageway floor was preserved to a length of 10 meters (33 feet) and a width of 1.3 meters (4 feet).

Importantly, Dr. Mazar found that the limestone floor abutted (literally touched) the foundational gatehouse walls. The floor also extended over the threshold at the entrance of the gatehouse (the eastern wall described above) and extended slightly outside the entrance to the gatehouse. This small portion of floor extending outside the gatehouse provides important insight into the function of the gatehouse. It shows that the massive fill against the eastern wall was used to support the chalk floor.

On top of the floor, Mazar found remnants of the latest use of the gatehouse (from the time of Jerusalem’s destruction in 586 b.c.e.). “These finds were unmistakable proof that here was the original First Temple Period floor—just as we have hoped,” she wrote after the 1987 season. Crucially, this floor sat about 1 meter (3 feet) above bedrock. This meant that there was a large volume of datable material below the floor. In the 1987 phase, Dr. Mazar removed all the later structures that cut into the floor. Meanwhile, the floor and the 1 meter of fill beneath were not fully excavated until the 2009 season.

In 2009, when Dr. Mazar returned to excavate the passageway fill, she found no discernible change in the nature of the material. Yet she decided to separate the upper half of the fill from the lower material. This separation was not based on anything she found; it was simply good archaeological practice and a decision made in advance.

Dr. Mazar explained why she did this in 2011: “The lime floor, which was discovered during our 1986 excavations comprised the latest floor of the gatehouse passageway. In general, floors in such busy places would definitely wear out very quickly and would require constant repairs: However, unlike its upper layers, the lowest earth fill, which directly overlays bedrock, would likely be undisturbed and would perhaps even provide finds that would reveal when the gatehouse had been constructed. The idea behind dividing the excavation of the earth fill beneath the lime floor was meant to isolate the original fill of the floor above later repair layers.”

Dr. Mazar’s rationale here was genius. By dividing the fill into two and separating the material in the upper part from the material in the lower part, she preserved the oldest, and arguably the most important, material. And as she expected, when the time came to dig, she found later-period items in the upper part of the fill. Meanwhile, also as expected, the bottom half-meter of fill contained no later-period items.

To date this material, Dr. Mazar compared the pottery she found in the passageway fill with pottery found in other 10th-century sites, most notably Khirbet Qeiyafa (a site irrefutably dated to the early 10th century). Based on the lack of red slip and wheel burnishing, as well as other similarities to pottery found at Khirbet Qeiyafa, Mazar was able to date her material (and the gatehouse) to the Solomonic period. In his report, Winderbaum agrees with Mazar’s dating of this earlier layer inside the passageway. As he writes, the pottery assemblage “should also be dated to the early Iron iia.”

Meanwhile, Finkelstein rejected Mazar’s rationale for separating the upper fill and the lower fill. He stated that the entire “fill must be evaluated together.” Using select pottery and other items uncovered in the upper fill that did date later, Finkelstein dated the entire fill down to bedrock to the seventh century.

But what about the fill and pottery at the bottom of the passageway that both Dr. Mazar and Winderbaum dated to early Iron iia? How does Finkelstein explain its presence? He doesn’t—he ignores the clear Solomonic material found in the lowest parts of the fill.

The Southern Chamber

Finally, we come to the southern chamber of the Ophel gatehouse. This room, which was remarkably well preserved, was first excavated in 1976, then again in 1986. In this room, Mazar found a white chalk floor similar to that in the central passageway. This floor also abutted (literally touched) the gatehouse walls, and appeared to partially enter the room from the central passageway. According to Mazar’s 1989 report, both remnants of the floor and the earth fill immediately beneath it (the “makeup”) were excavated together. This means that the entire fill, from top to bottom, was combined in excavation.

One wonders: Would we have a clearer understanding of this chamber if Mazar and her grandfather in 1986 had divided the fill into two sections, like Eilat did when she excavated the passageway in 2009?

Even still, the Mazars’ excavation of the fill under the chamber floor produced some dramatic results. According to Dr. Mazar’s 1989 report, she initially dated the pottery to the ninth century b.c.e., after the Solomonic period. However, in this same report she clearly identified pottery types that came into use in the 10th century and continued into the ninth century. The 1989 report also states that some pottery types were wheel-burnished, which is not a feature of 10th-century pottery.

In 2011, Dr. Mazar reexamined the pottery found in the 1986 dig and modified her dating of the chamber. Studying the pottery again, and considering it against information from sites and pottery not available back in 1989, Dr. Mazar determined that it was impossible to deduce whether the sherds were wheel-burnished or hand-burnished.

In her 2011 analysis, Mazar said that it was a mistake to date the pottery to its latest use (in the ninth century) and explained that it should instead be dated to the median period of use. This would date the pottery in the southern chamber to the 10th century.

Dr. Mazar’s reexamination and redating of an earlier excavation is not unusual in archaeology. In fact, it is good science to reconsider older findings in the context of newer findings and understanding. In this instance, however, some have a problem with Dr. Mazar’s reexamination of the 1986 dig. Why? Because the evidence indicates the pottery in this chamber also dates to the Solomonic period.

Winderbaum’s report on this southern chamber is interesting. He stated that “there were two fills beneath the floor, the lower of which supported an earlier floor that did not survive.” He somehow dates this lowest fill to the early Iron iib (eighth century b.c.e.). His methodology for dividing the fill is unclear, especially considering Dr. Mazar’s own conclusion on the fill. “The section of the fill proved uniform, with no changes to the stone plinth [foundation]” (Mazar, 1989). Perhaps Winderbaum has access to more information and data not included in Mazar’s final report. Nevertheless, he did not address Dr. Mazar’s redating of the uniform fill to the Solomonic period.

Is This Solomon’s Gatehouse?

The fact that three professional and respected field archaeologists have three differing opinions on the dating of the Ophel gatehouse is unsurprising—especially when you consider how much construction (and demolition) has occurred on the Ophel over the past 3,000 years. Archaeologically, the Ophel is one of the most challenging places on Earth to understand.

Dr. Eilat Mazar, the archaeologist with the most history with the site—who spent the most time thinking about and studying it—believed the entire Ophel gatehouse should be dated to the 10th century b.c.e. Winderbaum briefly excavated at the Ophel, under Dr. Mazar. Finkelstein hasn’t excavated at the Ophel at all.

What does the historical text say?

The book of Kings, believed to be compiled by Jeremiah in the late seventh and early sixth centuries b.c.e.—when the Ophel gatehouse was still in use—documents an impressive building project in Jerusalem under King Solomon. 1 Kings 9:10, 15 and other verses record how Solomon expanded Jerusalem from the ancient city of David northward onto the Ophel ridge. Here on the Ophel, he constructed his vast royal complex, which included his palace, the enormous armory building, the temple, and city walls and gatehouses.

“And this is the account of the levy which king Solomon raised; to build the house of the Lord, and his own house, and Millo, and the wall of Jerusalem, and Hazor, and Megiddo, and Gezer” (1 Kings 9:15). The historical record is clear and detailed: The 10th-century construction of Jerusalem and its walls, which include gates, was carried out by King Solomon!

Every reader will have to weigh the evidence and decide for himself. It would be helpful if we had more data available—more pottery, more of the walls and floors exposed, more of the gatehouse and its ancillary structures exposed. The only way to do this is to excavate!

For now, it is our view that when you consider the biblical record alongside the archaeological record, Dr. Mazar’s view is best. As she wrote, “Dating the construction of the fortification line in the Ophel to sometime in the second half of the 10th century makes King Solomon out to be the best candidate for its architect.”

The Large Tower

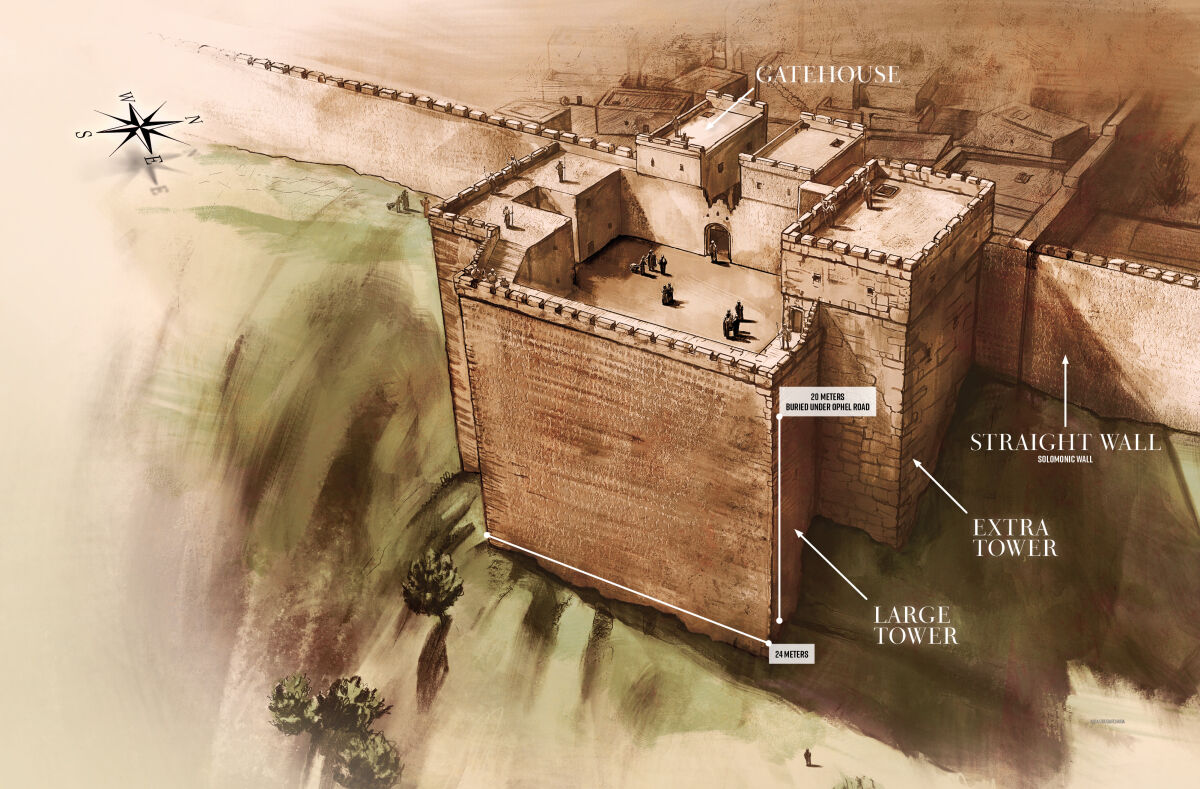

In addition to Solomon’s wall and this Solomonic gatehouse, there is still one more impressive structure just waiting to be uncovered.

The British government sent Capt. Charles Warren to conduct excavations in Jerusalem from 1867 to 1870. Warren wanted to excavate the Temple Mount, but this was impossible. Instead, he worked on the Ophel and dug a network of shafts and tunnels toward the southern part of the Temple Mount.

During these excavations, Warren discovered and mapped the dimensions of what is called the Large Tower. This structure, which is adjacent to and connected to the Solomonic gatehouse, is essentially a secondary wall of protection. Archaeologists have uncovered similar gatehouse towers, such as at Megiddo and Lachish.

A projecting tower defends the gate and forces those who approach to make a right-angled turn. Invading troops would then be on a narrow path, alongside the city wall, giving defenders a favorable vantage point for targeting invading troops.

Today the projecting tower that protects the gatehouse cannot be seen. Not only is it underground, but it is also under the Ophel Road, Jerusalem’s busy thoroughfare bordering the eastern side of the Old City. The engineers who built the Ophel Road can thank King Solomon; the Large Tower actually ballasts a roughly 50-meter-long section of the road, preventing it from slipping into the Kidron Valley.

“At the southeast angle of this extra tower we have found another wall going down towards the Kidron: It is 19 feet [6 meters] long, and then takes a turn to the southwest,” Warren wrote in a report on Oct. 2, 1868. “We have not followed it farther. It has been examined to a depth of nearly 40 feet (12 meters), the stones are well-dressed ashlar; in size about 1.6 to 2 feet high, and 2 to 3 feet long. An isometric projection from the extra tower and the projecting wall is enclosed. It can be seen that, if the debris were to be shoveled into the valley, there would still be a scarped wall for Ophel of from 40-60 feet in height—which is only dwarfed by the stupendous height of the [Temple Mount] wall alongside.”

Warren later dug a shaft to the base of the wall, revealing that the wall stood at a height of 20 meters (66 feet) and a length of 24 meters (80 feet). The dimensions he took revealed that this structure was as tall as the aboveground portion of the Western Wall!

The Significance

Compared to other fortified walls, the Large Tower on the Ophel is extraordinary. It is 6 meters (20 feet) taller than the tallest part of the Great Wall of China. It is 4 meters (13 feet) higher than the walls of Nineveh, the capital of ancient Assyria. The preserved portion of the projecting tower in Jerusalem is 6 meters (20 feet) higher than the visible portion of the Ishtar Gate, the gigantic gate of King Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon and perhaps the most famous ancient gate in the world.

By all accounts, the Solomonic gate and its projecting tower is immense, almost beyond belief. The colossal size of the projecting tower dwarfs any other discovery from the biblical world found in Israel. Details about King Solomon’s wall and the large gatehouse are well established. Solomon’s monumental Jerusalem exists. But perhaps, only by future excavation of the third feature—the most monumental of all—the Large Tower, will the true grandeur of Solomon’s Jerusalem be unavoidably obvious.