They tamed the high seas centuries before the Vikings and the buccaneers. They rode elephants while the rest of the world was riding horses. They were the world’s luxury craftsmen millenniums before the Swiss were making watches. And they were one of Israel’s most steadfast allies.

The Phoenicians, an ancient civilization located in the area of modern-day Lebanon, are credited with some remarkable achievements. The Bible reveals fascinating details about the Phoenician civilization. It also explains one of the primary reasons this civilization flourished.

A significant part of the Phoenicians’ success can be attributed to their relationship with Israel. The Israelite-Phoenician partnership lasted centuries and impacted both civilizations, allowing both nations to experience their golden ages at the same time.

Who Were the Phoenicians?

The name “Phoenicia” comes from the ancient Greeks. Homer wrote in the Iliad of fine craftsmanship that “far exceeded all others in the whole world for beauty; it was the work of cunning artificers in Sidon, and had been brought into port by Phoenicians.” High-quality craftsmanship, skill in commerce, and the production and trade of luxury goods were hallmarks of ancient Phoenician culture.

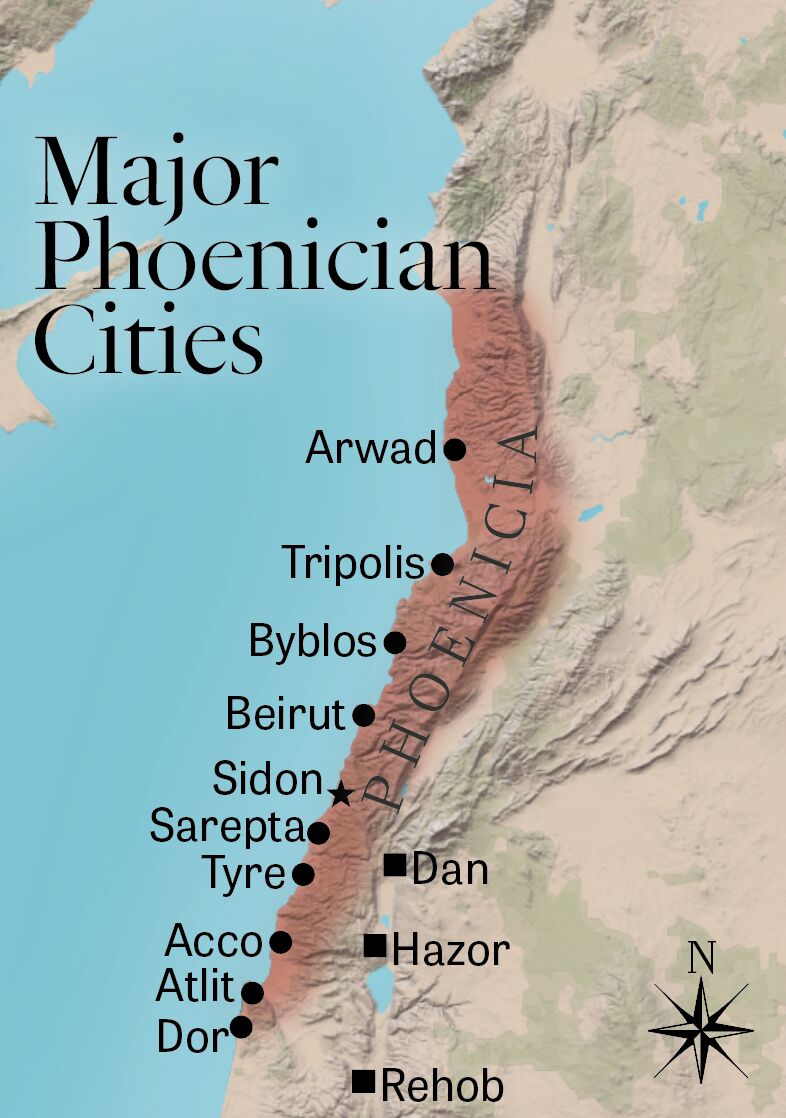

The first biblical reference to the Phoenicians is in Genesis 10: “And Canaan begot Zidon his firstborn, and Heth” (verse 15). Zidon, or Sidon, was one of the major Phoenician city-states of the region. (Other known Phoenician city-states include Tyre, Byblos and Beirut, Lebanon’s capital city.)

The Phoenicians are not classifed as a civilization or empire, like Assyria or Babylon. Rather than being identified as a common culture or people, the Bible (as well as Greek literature) identifies the early Phoenicians according to the city-state they belonged to.

Sidon and Tyre are the two main cities referenced in the Hebrew Bible. While Phoenician, these two cities were within the originally assigned borders of the territory allotted to the Israelite tribe of Asher.

God intended much of what is modern Lebanon to be part of the original allotment for the 12 tribes of Israel. Joshua 11:8 describes the Israelites chasing Canaanite armies “unto great Zidon.” Joshua 19 describes the territorial boundaries for the tribe of Asher, which would include the following cities: “Rehob, and Hammon, and Kanah, even unto great Zidon; And then the coast turneth to Ramah, and to the strong city Tyre” (verses 28-29; kjv). References to “great Zidon” and “the strong city Tyre” demonstrate how powerful these two key Phoenician cities were compared to the other Canaanite entities in the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age (circa 1400–1050 b.c.e.).

But Israel did not follow through on God’s command to conquer this territory (Judges 1:31-32). Judges 3 states: “Now these are the nations which the Lord left … namely, the five lords of the Philistines, and all the Canaanites, and the Zidonians, and the Hivites that dwelt in mount Lebanon, from mount Baal-hermon unto the entrance of Hamath” (verses 1, 3).

History and archaeology can teach us a lot about these close neighbors of Israel and shed light on the kingdom of David and Solomon.

Cedars From Lebanon

The Israel-Phoenicia alliance was built mainly on trade and commerce. The Phoenicians had access to many raw materials. Through their maritime ventures, the Phoenicians traveled the Mediterranean and established colonies in Cyprus, Crete, North Africa, Spain and some parts of France. Israel, through Tyre, had access to these extensive trade networks. And Tyre, through Israel, had access to the most powerful economy in the region.

One of the Phoenicians’ most well-known raw materials was home grown: cedarwood.

The cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani) today grows natively in Lebanon, Israel, Syria, Turkey and Cyprus. The timber from these trees, which grow up to 35 meters (115 feet) tall, has been used in construction since ancient times.

Cedarwood is especially prized for boatbuilding; it is highly durable, easy to shape and mold, and resistant to deterioration in seawater. Having such an abundant supply of quality wood so close to home surely was one of the reasons the Phoenicians were able to become such skilled sailors.

King Solomon requested cedarwood for the construction of the temple in Jerusalem (2 Chronicles 2:15). The Tyrian King Hiram told him: “My servants shall bring them down from Lebanon unto the sea; and I will make them rafts to go by sea unto the place that thou shalt appoint me …” (1 Kings 5:23).

The Phoenician technique of shipping cedarwood to their clients is well documented. A wall relief from the palace of Assyrian King Sargon ii shows Phoenician sailors transporting large quantities of logs from a port across the sea.

Archaeological excavations on the Ophel in Jerusalem have provided evidence that the cedars of Lebanon made their way to this capital city. Amid the charred remains of the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem (586 b.c.e.), Benjamin and Eilat Mazar found evidence that several types of wood, including cedar of Lebanon, were used in the construction of the royal building they were excavating (Qedem 29).

Ivory in Jerusalem

The Bible relates that during the time of Solomon, ivory was one of the main commodities imported into Israel with the help of the Phoenicians. “For the king had at sea a navy of Tarshish with the navy of Hiram; once every three years came the navy of Tarshish, bringing gold, and silver, ivory, and apes, and peacocks” (1 Kings 10:22). Verse 18 even says that Solomon’s throne was made of ivory.

Evidence of 10th-century b.c.e. ivory was discovered in Jerusalem by Dr. Eilat Mazar. Remarkably, the only known parallel discovery was found in ancient Phoenicia.

While excavating the palace of King David, Dr. Mazar’s team uncovered a 10-centimeter-long (3.9 inches) stylized ivory inlay. It consisted of two identical halves that would have adorned either side of an iron shaft, perhaps part of a knife or mirror. The ivory item was found alongside an elegant black-on-red Cypriot juglet in an area of the palace that was dated through carbon dating and pottery analysis to the second half of the 10th century b.c.e.

According to Dr. Mazar’s preliminary excavation report, an identically designed inlay was discovered attached to a sword at the excavations of the Phoenician site of Achziv on the northern coast of Israel. The sword was alongside other funerary goods that dated to the 10th century b.c.e.

The discovery of a Phoenician-style ivory handle in Jerusalem makes perfect sense. As Dr. Mazar wrote in her excavation report, “The ivory inlay and the fine Cypriot imported jug … are markers of the luxury of the assemblage, as well as the connection to the Phoenicians, who were renowned, among other things, for their maritime commerce on the Mediterranean shores and their expertise in ivory carving.”

Purple Dye From Shikmona

Tel Shikmona is an archaeological site on Israel’s northern coast, near the modern-day city of Haifa.

When Israeli archaeologist Joseph Elgavish first excavated the site in the 1960s and 1970s, he found evidence of a flourishing and productive 10th-century b.c.e. settlement, which he called “a city from the days of David and Solomon.”

However, there remained gaps in the understanding of the site. It’s not on an easily accessible harbor, making it an unusual choice for a maritime settlement. It is fortified despite not being situated on any apparent strategic territory.

In 2016, the University of Haifa began piecing together what made Tel Shikmona so significant.

While both Israelite and Phoenician pottery were discovered at the site, the presence of larger amounts of Phoenician pottery indicated it was primarily a Phoenician settlement. However, the existence of both styles of pottery side by side indicates a harmonious relationship between the Israelites and Phoenicians, as described in the Bible.

Analysis of purple-stained clay vats and other tools found at the site helped clarify Tel Shikmona’s purpose: It was a mass production facility for Tyrian purple. And it is the first one from the biblical era to be discovered. The vats date to all 10 different Iron Age strata, showing both the longevity of the site and the value of its commodity.

The Phoenicians were known for their near-monopoly on the production of purple dye, also known as Tyrian purple. They harvested the dye from the murex shellfish, a sea snail with natural purple coloring that thrived off the coast of Lebanon.

Tyrian purple was a highly valued luxury for a long time; the fourth-century c.e. Roman Emperor Diocletian, in his Edict of Maximum Prices, lists 1 pound of the dye as costing 150,000 denarii, three times the value of gold. Only the richest in society could afford Tyrian purple. This is why, today, we associate the color purple with royalty.

2 Chronicles 2:3 and 6 reveal that Solomon asked King Hiram to supply a workman who was skilled in working with “purple” dye for the construction of the temple.

According to Prof. Ayelet Gilboa and Dr. Golan Shalvi, two of the main scholars affiliated with the Tel Shikmona excavations: “Because it was the most active purple production factory and the closest to Jerusalem—and in fact the only one known to us from these periods—it was most likely the prestigious supplier of dyes for the temple.”

Golden Partnership

The alliance between Israel and the Phoenicians is unique in the Bible. Few of Israel’s neighbors were as supportive of Israel as the Phoenicians. Using the Bible together with archaeology, it becomes apparent that Phoenician history is Israelite history.

Israel and Tyre reached their golden ages at the same time, with kings from both nations willing to work together to accomplish exploits. The two nations used each other’s strengths for simultaneous prosperity. In fact, even with its trade routes and scattered colonial possessions, it is unlikely a city-state like Tyre would have become as wealthy as it did if it had not been for the backing of the Israelite empire.

Tyre’s association with the strong, prosperous empires of David and Solomon undoubtedly contributed to it becoming an economic powerhouse. Solomon’s Phoenician-engineered temple would have been the pinnacle of artisanship from a culture already renowned for fine craftsmanship. And there is further evidence of this interconnectedness in the shared language of the Phoenicians and Israelites.

Sidebar: King of Tyre

King Hiram is the Phoenician ruler that the Bible describes ruling over Tyre during the reigns of kings David and Solomon. Menander of Ephesus, a second-century b.c.e. Greek historian, recorded a Tyrian king list based off of the Phoenician king lists. Various Phoenician kings on the list have been cross-corroborated archaeologically.

This document mentions King Hiram i who ruled during the 10th century b.c.e. Menander even further expounds on Solomon and Hiram’s interactions.

For archaeological evidence that relates to King Hiram: A royal sarcophagus from the 10th century b.c.e. was discovered at the Phoenician city of Byblos, inscribed with the words “Ahiram, King of Byblos.”

The Bible specifies that Hiram was “king of Tyre,” however, so the sarcophagus may belong to another king (Byblos was situated further north along the coast). But it is possible the site was under King Hiram’s jurisdiction within wider Phoenicia. There is biblical evidence of crossover in Phoenician regional names, given that Solomon refers to the Tyrian Hiram’s people as “Zidonians” (1 Kings 5:20).

Nonetheless, the discovery of this inscription proved that the name of the biblically famous king of Tyrus was in use during that era, in a region not far from Hiram’s headquarters.