“And he put garrisons in Edom; throughout all Edom put he garrisons, and all the Edomites became servants to David” (2 Samuel 8:14).

This chapter famously accounts David’s victories in the south, conquering the land of Edom and bringing it under his control via a managed network of military outposts. 1 Chronicles 18 provides additional details of this event and concludes with a similar statement, saying David “put garrisons in Edom; and all the Edomites became servants to David. And the Lord gave victory to David whithersoever he went” (verse 13).

In the early 20th century, archaeological research spearheaded by Prof. Nelson Glueck demonstrated that Edom was a major industrial base for the kingdom of Israel in the 10th century b.c.e. More recent excavations, especially at Faynan and Timna, have confirmed Glueck’s conclusion and have shown that the copper mines in this region reached peak power and productivity during the 10th century (see page 99).

Extensive mining operations would have required security. The abundance of copper (and probably other minerals too)—and the flow of goods across the sparsely populated Negev region of southern Israel en route between Arabia and the Mediterranean Sea—would have been a temptation for Israel’s enemies and certainly the local Edomites, known for their hostility. The establishment of military outposts “throughout all Edom” was a strategic necessity, not just to defend the mines, but to protect the trade routes from the Gulf of Aqaba to Jerusalem.

Surprisingly, in the research into the kingdom of Israel under David and Solomon, these biblical garrisons appear to have been largely overlooked. This is not due to a lack of evidence or archaeological excavation.

This could now be changing, however, thanks to a recent marshaling of remarkable evidence—old and new.

‘We Will Not Be Defeated’

The events of Oct. 7, 2023, shocked Israel and the world. Following the horrifying massacre perpetuated by Hamas, Israelis rallied together to support the war effort and bolster national unity. In an effort to educate Israelis about their national history, the Israel Antiquities Authority (iaa) hosted a four-part online lecture series between October 23 and 26, titled “We Will Not Be Defeated: From Crisis to Revival in the Archaeology of the Land of Israel.”

Dr. Tali Erickson-Gini, the iaa’s former archaeology inspector for the Southern Negev, delivered the first lecture on a topic related to her area of jurisdiction and expertise. Her presentation was titled “The Early Challenges of the United Kingdom of Israel: Facing the Edomite Frontier 3,000 Years Ago.” Dr. Erickson-Gini began with a bang: “Most people, even Israelis, are not so aware of the fact that 3,000 years ago, there were Hebrew soldiers there [in the Negev Highlands] and there were Hebrew fortresses there.”

There is, in fact, a significant amount of evidence attesting to Israel’s control of this area in the 10th century b.c.e., she stated. Unfortunately, as Erickson-Gini explained, the research has been “swept under the rug.” This is partly due to the “controversies between archaeologists and researchers,” she explained. (In a Nov. 5, 2023, interview with aiba, Dr. Erickson-Gini explained her reticence to dive into the “shark tank” that is the debate about Israel’s Iron Age.) “But I think today, as we have more information, more data coming out from different research groups, we’re able to see very clearly that we’re talking about something that’s militarily [oriented],” she said.

Garrisons—by the Dozens

In her lecture, Erickson-Gini reviewed the history of the discovery of dozens of early fortresses within the Negev desert. Some of the garrisons were first identified during a British Army survey in the early 1900s led by Sir Leonard Woolley and T. E. Lawrence (the famous “Lawrence of Arabia”) and published in their 1915 book The Wilderness of Zin. The researchers could not date the sites with absolute confidence but concluded that they were “very early.” Later, several researchers, including Professor Glueck, attributed their use to the early Iron Age. They also concluded that these fortresses fell out of use around the time of the invasion of Pharaoh Shishak at the end of the 10th century b.c.e. (circa 925 b.c.e.)

One of the leading experts in these Negev sites was the late Dr. Rudolph Cohen. Dr. Cohen and other colleagues concluded that the structures dotted throughout the Negev were military fortresses. There are, of course, those who disagree. These include the late Prof. Beno Rothenberg, as well as Prof. Israel Finkelstein, who believe that these were perhaps some sort of earlier settlements or even animal pens. Dr. Erickson-Gini has researched the sites and strongly disagrees with their opinions.

According to Cohen’s extensive research, these sites are notable for their lack of burial and cultic remains, as well as a lack of oil lamps—otherwise ubiquitous finds that would be expected for a settlement. He also noted the presence of large storage vessels at the sites, necessary for food and water supplies to sustain whomever was posted within the structures. Dr. Cohen also noted the presence of wheel-made pottery comparable to other examples found in Judah, which indicates the garrisons were associated with settlements in the north. Dr. Erickson-Gini noted that establishing settlements would have been impossible due to the lack of reliable water sources.

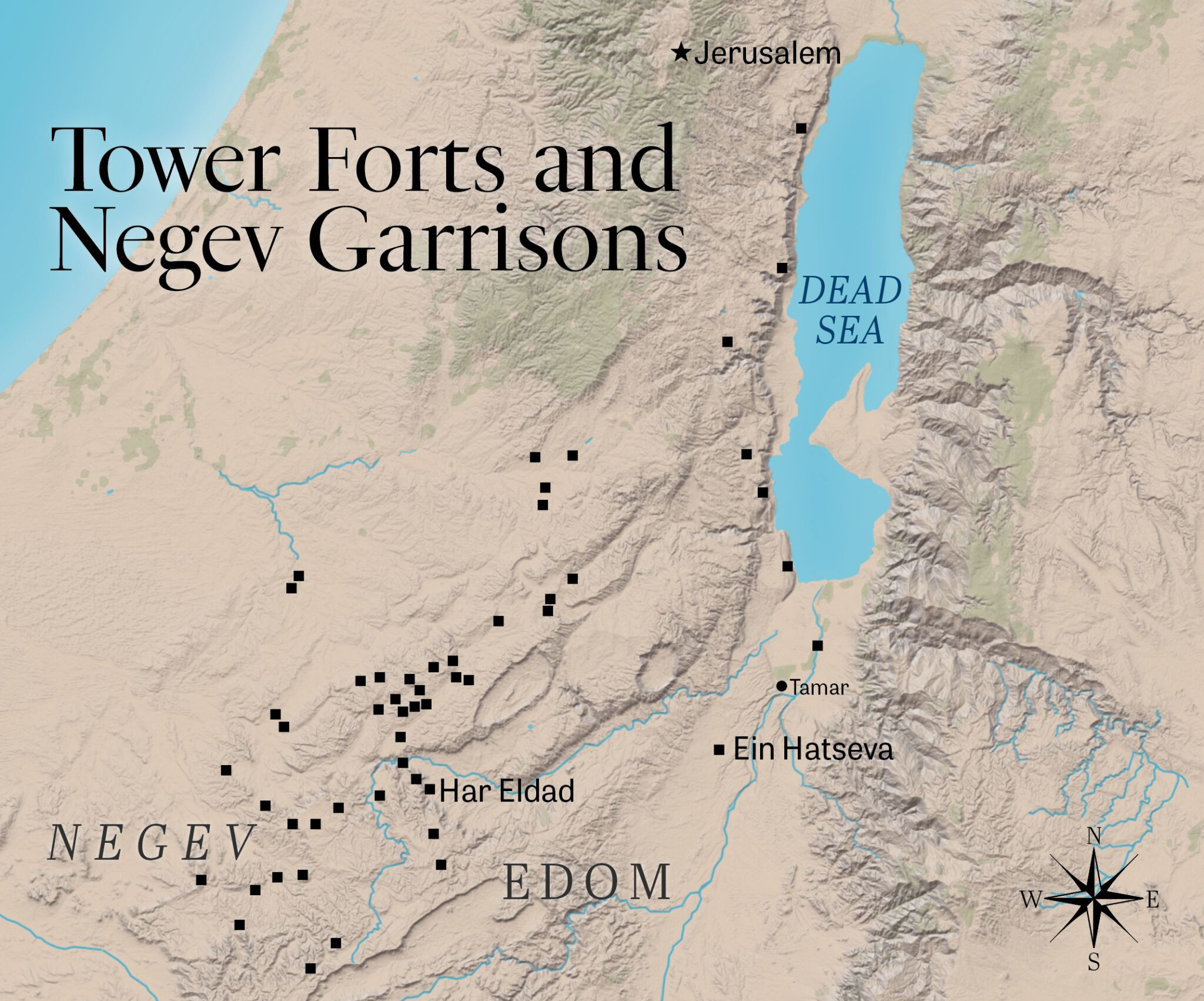

Citing Ben Gurion University’s Uri Nissani—whose 2023 master’s thesis addresses and maps these fortresses—Dr. Erickson-Gini noted the existence of “over 60” fortification sites and added: “I would say that there’s probably even more fortifications that have not been investigated. I know for a fact that there have been areas that have not been properly surveyed yet …. There are smaller sites, that are towers, that are dotting along roads going between the bigger sites …. I can’t even bring you, in this presentation, everything. There’s just too many. We’re talking about at least 60 of them. And there’s actually more than that.”

The strategic placement of these fortresses is important. Erickson-Gini said: “In my mind, for all the years that I’ve worked down here—and I’ve worked in this area for over 30 years—one thing that struck me very strongly is how they are situated along … what would have been ancient roads. You can see them particularly along this front facing the Ramon crater, facing Edom. But we also see them blocking basically every single wadi [deep river gorge] that is going from south to north. … You can see how these forts, and even small towers—some of them have never been excavated, or they’ve been excavated and they haven’t been reported—you can see how they’re lining roads, they’re lining along wadis that are used as roads, and they’re blocking wadis. So there was a great amount of control exerted through this area.”

Dr. Erickson-Gini has divided the many fortresses into three potential categories based on size and layout. The first category is comprised of small square or rectangular tower-like forts divided up into interior chambers. The second is made up of medium-size rectangular or irregular rectangle forts, with a central courtyard surrounded by casemate walls. The third consists of large, rectangular or irregular fortresses, with much larger open central courtyards, ringed by chambered casemate walls. “Probably the most important is that [these different fortress types] are coming from the same chronological phase,” she said. “There’s no difference chronologically if the shapes are different.”

Dr. Erickson-Gini also noted the rough handmade pottery items found at these sites, termed “Negebite ware.” This pottery is “particularly abundant in the 10th century and maybe … the late 11th century b.c.e.” Importantly, Dr. Mario Martin discovered that these Negebite ware vessels had high percentages of copper slag inclusions (Erickson-Gini speculated that this helps in heat conductivity). Martin noted in his research that these vessels were not the product of unskilled nomadic settlers, as had been thought previously; rather, they must have originated in these major Arabah Valley areas of copper production (particularly Faynan and Timna).

Lynchpin Site 1: Ein Hatseva

One of the key sites highlighted by Dr. Erickson-Gini, and representative of the small forts, is Ein Hatseva. This site is situated in the central Arabah Valley roughly 40 kilometers (25 miles) south of the Dead Sea.

Ein Hatseva is a remarkable archaeological site that has been popularly identified as biblical Tamar (Ezekiel 47:19; 48:28; 1 Kings 9:18; 2 Chronicles 8:4; also identified as the Roman and Byzantine Tamara). The tel exhibits several periods of use, including the remains of a later Iron Age fortress, with famously heavily slanting walls (commonly attributed to “Amos’s earthquake” of the mid-eighth century b.c.e.). An impressive, large Roman fortress was also discovered at this site.

One of the most intriguing features, however, was the “very little known” discovery of an earlier Iron Age tower, first found at the site by Dr. Cohen and Yigal Israel. This smaller, earlier tower fort was dated firmly to the 10th century b.c.e. through both radiocarbon dating and pottery dating. The pottery is exactly the same as the Iron iia Negebite ware found throughout the region, with the same slag inclusions. Later excavations in and around this tower were conducted by both Dr. Doron Ben-Ami and Dr. Erickson-Gini.

This small, 10th-century tower fort is identical—in size, style and material finds—to a chain of other small tower outposts interspersed at regular intervals along the Dead Sea route to the north (with a possible example as far north as Qumran, on the northern end of the Dead Sea). This chain of forts extends as far south as Tell el-Kheleifeh, on the Red Sea coast (although the dating of the Tell el-Kheleifeh site to the 10th century is uncertain). Tell el-Kheleifeh is identified with biblical Ezion-geber, the port of Solomon’s navy (1 Kings 9:26). “All of these [forts] are connected with the copper trade in some way,” noted Dr. Erickson-Gini.

These small outposts are what Erickson-Gini termed “podium” towers, or squarish towers integrated into and atop podium-like stone mounds. Interestingly, they are entirely enclosed by walls, without side entrances. According to Dr. Erickson-Gini, “You have to go to the top and go down, probably with ladders to get into them.” Unfortunately, “most of them have not been investigated, or they’ve been investigated and not published, for example, by Yohanan Aharoni. But we know for a fact that they’re early. Almost all of them have some kind of earlier pottery and Midianite pottery … the painted pottery of the Qurayyic tradition, which we find in the matrix underneath.” (Qurayyah Painted Ware is a pottery type dating to the end of the second millennium b.c.e.)

Following our interview with Dr. Erickson-Gini at Ein Hatseva, we visited four additional, relatively proximate sites recommended by her: Mesad (Fort) Mazal, Mesad Gozal, Mesad Zohar and Rosh Zohar. These sites were remarkably similar in construction, size, style and materials. Some of the sites had barely been excavated—a fact Erickson-Gini lamented in our interview, saying, “Most researchers are not even aware that they exist.”

The obvious similarities between these fortresses with the one at Ein Hatseva, which has been firmly dated to the 10th century b.c.e., strongly indicates that these sites date to the same period and were part of a deliberately placed string of north-south guard stations.

Lynchpin Site 2: Har Eldad

The fortress at Har Eldad, situated roughly 100 kilometers (62 miles) southwest of the Dead Sea and much deeper in the Negev Desert, is an example of one of the larger fortification types. This site was excavated in 2017 by Dr. Haim Mamalya and Dr. Erickson-Gini. This significantly larger fortress, which overlooks a wadi, is distinguished by a large open central courtyard and an external casemate wall all around.

During their 2017 excavation, the archaeologists uncovered a clay vessel, known as a wine krater. The discovery of this vessel, which was used for mixing wine, was important for two reasons: 1) It was complete and perfectly preserved; 2) it contained grape seeds within and around the vessel. The seeds were an especially crucial find as they could be readily carbon-dated. To what time period did the remains belong?

The carbon-dating results (facilitated through Prof. Erez Ben-Yosef, who had been at the site with his own students) pointed to somewhere between the end of the 11th and mid-10th centuries b.c.e.—precisely aligning chronologically with the rule of King David.

Not only that, the vessel itself was of a particular type discovered a few weeks earlier at Khirbet al-Ra’i and part of a Judahite assemblage found during the excavations by Prof. Yosef Garfinkel and Saar Ganor at the site in the Judean Shephelah (lowlands). The Khirbet al-Ra’i assemblage was also dated to the same time period: around 1000 b.c.e. “[H]ere we are seeing some more things that we’re tying in with the northern pottery that Cohen had noted earlier,” Dr. Erickson-Gini stated. “We were lucky enough to be able to find the seeds and the vessel together and to be able to date it.”

Most of the dozens of fortresses scattered throughout the Negev, and territorial Edom, have yet to be properly excavated. But the pattern is the same. The sites have the same primary layouts (small podium towers and medium-to-large courtyard fortresses with casemate walls); the same style stone construction; the same pottery, which can be dated to the same time period (Iron iia Negebite ware); the same pottery connected to copper use and trade, which research at Timna and Faynan shows spiked during the 10th century b.c.e.; and even more conclusively, carbon-dated material returning the same 10th-century b.c.e. date.

There’s the same material underneath these fortress structures (where excavated), identified as earlier, end-of-the-second-millennium “Midianite” (Qurayyah Painted) ware; the same end of use in the late 10th century b.c.e., at the time of Shishak’s invasion; and the same strategic placement of these garrisons—all along trade routes, ancient roads and wadis.

All of this evidence should be considered alongside the biblical text, which describes a chain of garrisons being built in this area at this exact time. Dr. Erickson-Gini concluded: “From my knowledge of these places—where they’re placed along the roads, the topography—I don’t think that there’s any doubt that we’re talking about something to do with some kind of fortifications in the Negev Highlands and control of this region between Edom and the area of Judah under the united monarchy.”

King David’s Garrisons

1 Samuel 14:47 describes King Saul’s initial battles against the Edomites. The Bible later describes Saul’s alliance with a notorious Edomite named Doeg, who presided over a devastating massacre of men, women, children and babies of the priestly town of Nob, following aid given to David by one of the individuals there (1 Samuel 22:21-22). This was one of many outrageous acts instigated by the Edomites, and it may have been the reason behind Joab’s later vengeance on the population (1 Kings 11:15-16).

During David’s reign, however, the dynamic changed. Psalm 60 describes a situation of desperation for David in relation to Edom and Syria. “O God, thou hast cast us off, thou hast scattered us, thou hast been displeased; O turn thyself to us again. … [O]ver Edom will I cast out my shoe …. Who will bring me into the strong city? who will lead me into Edom? Wilt not thou, O God, which hadst cast us off? and thou, O God, which didst not go out with our armies? Give us help from trouble: for vain is the help of man. Through God we shall do valiantly: for he it is that shall tread down our enemies” (Psalm 60:1, 8-12; kjv).

2 Samuel 8 and 1 Chronicles 18 record David’s victory against this Edomite-Syrian alliance in the “valley of salt” (Dead Sea region). Following his victory, “he put garrisons in Edom; and all the Edomites became David’s servants. Thus the Lord preserved David whithersoever he went” (1 Chronicles 18:13; kjv). “Preserved” is the same Hebrew word David used in his prayer in Psalm 60:5, when he asked God to “save” him (kjv).

2 Chronicles 8:17 records Solomon’s safe passage to “the sea-shore in the land of Edom”—undoubtedly facilitated by these defensive garrisons along the route that David had installed.

Going Back to the Bible

For early 20th-century excavators, such as Nelson Glueck, it was routine to use biblical passages like these to illuminate findings on the ground. “Each generation has had its own biblical archaeology,” write Prof. Yosef Garfinkel, Dr. Igor Kreimerman and Dr. Peter Zilberg in Debating Khirbet Qeiyafa: A Fortified City in Judah From the Time of King David (Chapter 5, “The Bible and Archaeology: Methodological Remarks”). “In the days of Albright and Wright [and, it might be added, Glueck] it was theologically oriented. … Albright’s conception of the relationship between the Bible and archaeology is best expressed in his own words: ‘Discovery after discovery has established the accuracy of innumerable details of the Bible as a source of history’ …. Today, this statement seems very naïve” to those in modern scholarship.

Professor Glueck is known for having made similar statements. He wrote in Rivers in the Desert: A History of the Negev: “It may be stated categorically that no archaeological discovery has ever controverted a biblical reference. Scores of archaeological findings have been made which confirm in clear outline or exact detail historical statements in the Bible. And by the same token, proper evaluation of biblical descriptions has often led to amazing discoveries.”

Comparing modern scholarship with the sentiments of earlier archaeologists, Garfinkel, Kreimerman and Zilberg lament: “Today we are in a postmodern and deconstructive era. Everything is relative, there is no right or wrong.” But “[b]iblical archaeology was not ‘born in sin,’ as some scholars think today,” they write, pointing out the fundamental contributions and methodologies of these early archaeologist forebears.

When it comes to her Edomite garrisons, Dr. Erickson-Gini speaks to the same theme: “I know that in recent years it hasn’t been so popular to use the Hebrew Bible as an historical source. But I think we’re starting to go back to that.”