‘Alas, poor Yorick!” one imagines Megiddo’s excavators to have declared, as they unearthed the skull of a princely Canaanite individual in 2016. Except, this particular skull was in somewhat more nightmarish shape than that of Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

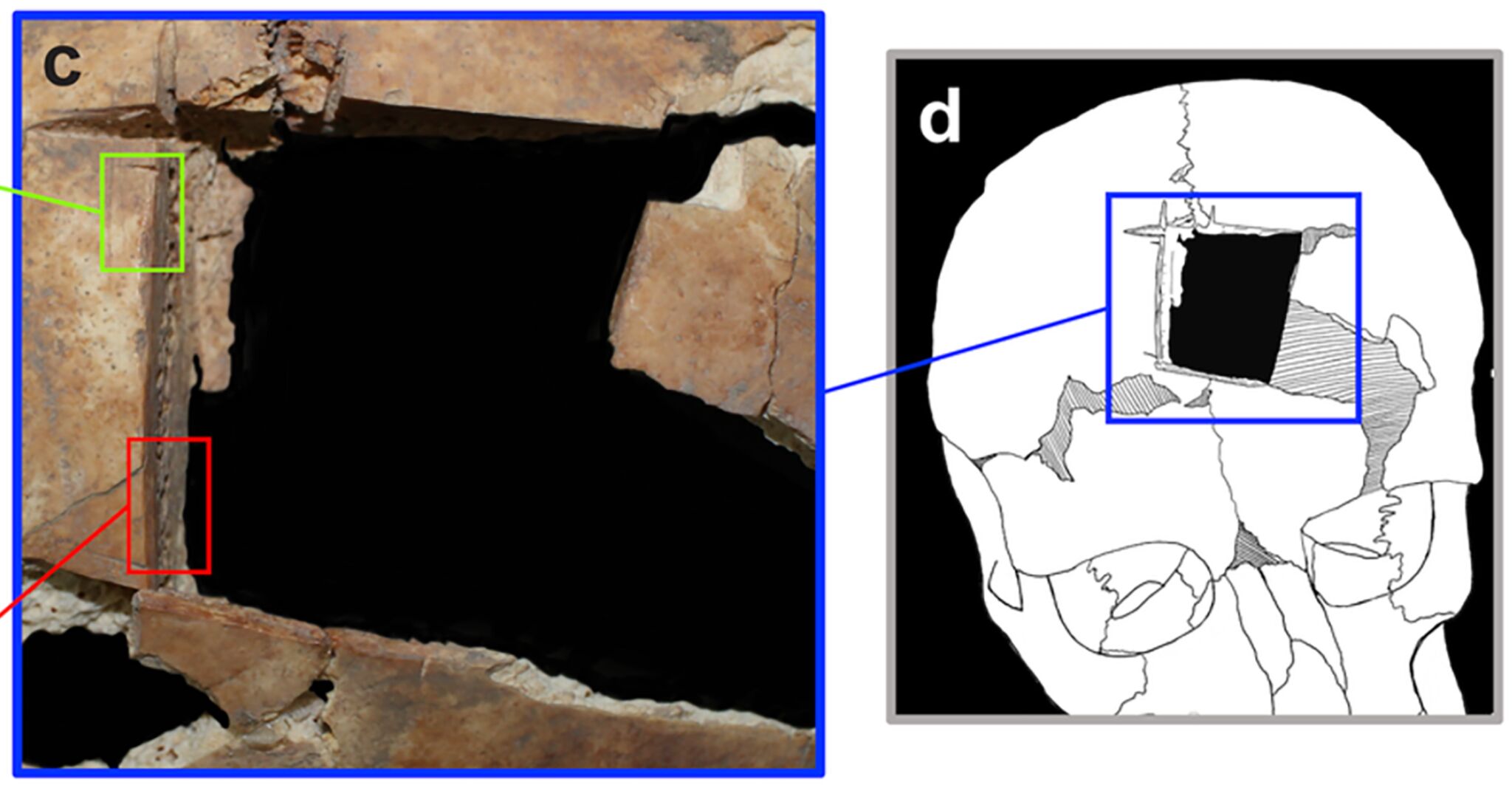

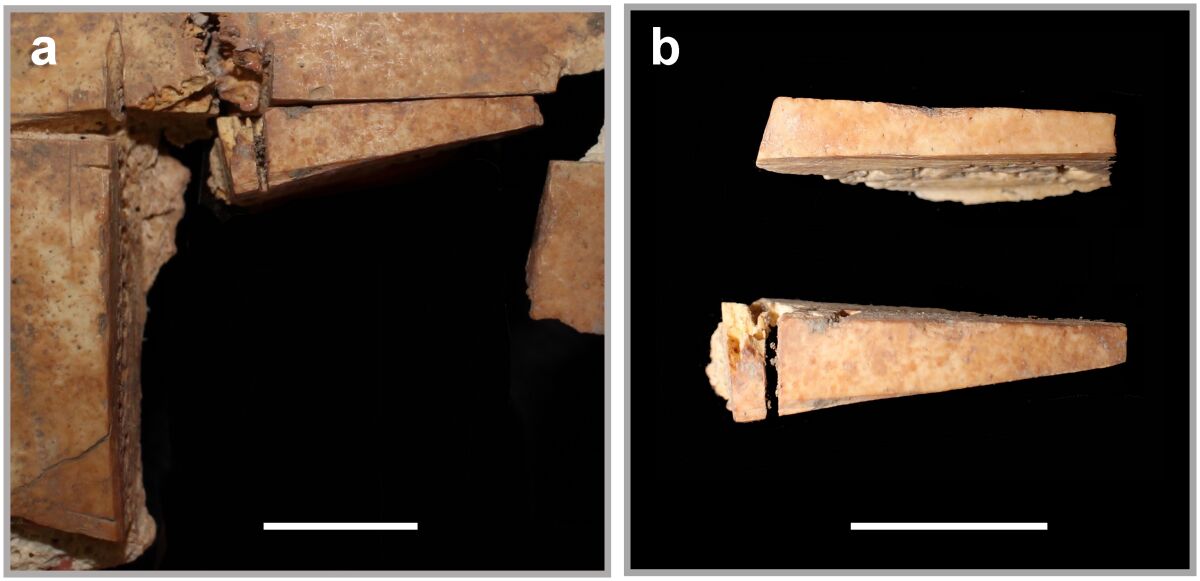

Positioned above the brow was a large, square hole that had been sawn through the skull while the individual was still alive—the earliest example of a cranial surgery known as trephination ever discovered in the ancient Near East. While certain other examples of trephination consist of a circular hole (the product of some form of analog drill), this was a painful case of repeated sawing and prying apart of bone fragments to create a square opening.

Analysis of this remarkable discovery—as well as the overall sickly condition of this 15th-century b.c.e. individual and his nearby buried brother, both of whom died young—was published last week in the scientific journal PLOS ONE.

Analysis of the brothers’ skeletons was led by Rachel Kalisher, Ph.D. candidate at Brown University’s Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World. The paper was published in conjunction with researchers Melissa Cradic, Matthew Adams, Mario Martin, and Israel Finkelstein.

“We have evidence that trephination has been this universal, widespread type of surgery for thousands of years,” Kalisher notes. Still, such surgery is far less common in the ancient Near East, and this discovery represents the earliest-known example for this region (the skeletons dating to circa 1550–1450 b.c.e.). “[T]rephinations have proven medicinal benefits, and are most often cited in the archaeological literature as curative to head trauma by releasing pressure buildup in the head.” Still, Kalisher points out, “You have to be in a pretty dire place to have a hole cut in your head.”

The trephination was intended to heal the individual, but the skull does not show any real signs of bone healing, so the patient probably died shortly after or even during the procedure.

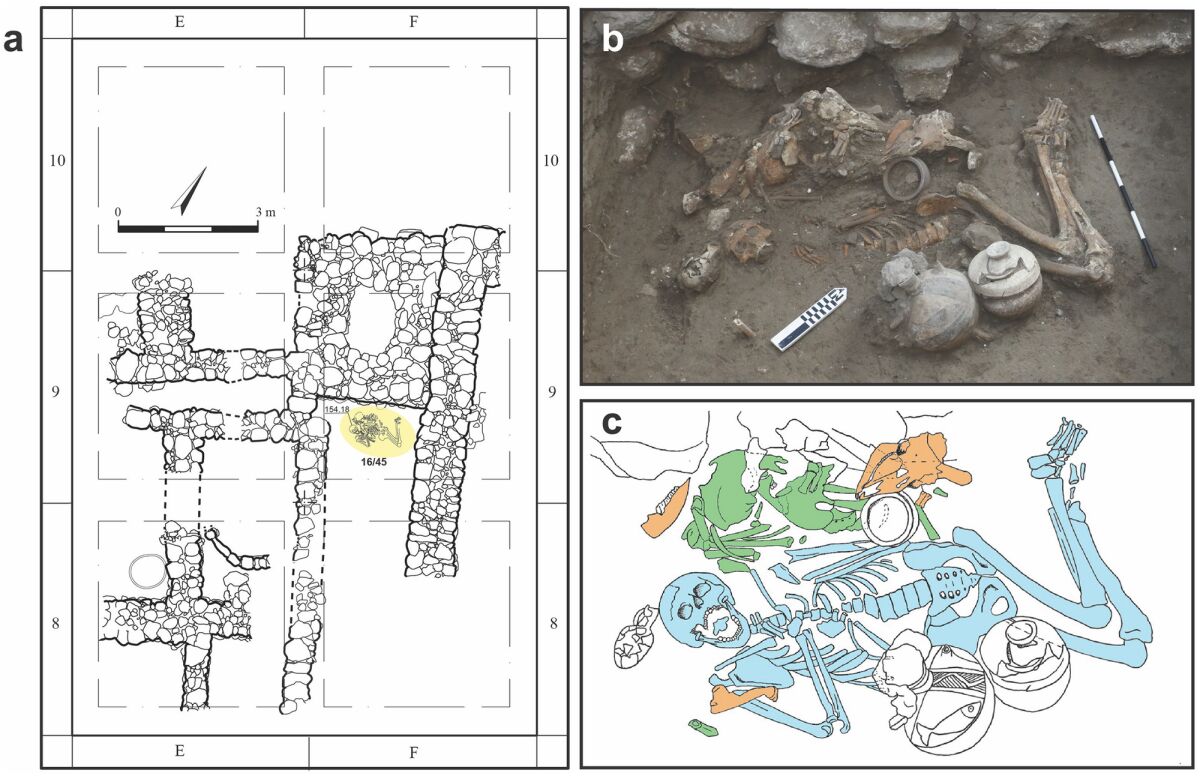

The Bronze Age skeletons were originally found buried underneath the floor of a domestic structure at Megiddo (a traditional burial practice of this period). dna analysis concluded that the two skeletons discovered were indeed brothers. Since it appears they died at different times, their burial together indicates that the previously deceased brother was dug up and reburied with his kin.

What is particularly interesting about these two individuals is that they were both quite sickly. Since they share the same dna, it is theorized they both had the same proclivity to illness. One individual died either in his teens or early 20s, and the other, somewhere between ages 21 and 46 (the brain-surgery “patient”). The bodies of both were ravaged by various maladies. The laundry list includes: evidence of anemia or childhood nutritional deficiency; our brain-surgery “patient” also had a healed nose fracture; teeth irregularities; and most significantly, as summarized by Brown University, a full “third of one brother’s skeleton, and half of the other brother’s, shows porosity, lesions and signs of previous inflammation in the membrane covering the bones—which together suggest they had systemic, sustained cases of an infectious disease like tuberculosis or leprosy.”

Still, as highlighted by the researchers, it is believed that the brothers would have survived longer with their illnesses as compared to “commoner” contemporaries suffering from similar illnesses, given their access to privileged treatments. (The more privileged standing of these individuals is reflected, for example, by their tomb being adorned with high-quality foods and pottery similar to nearby “royal” tombs.) Others in this same area may have had the same disease that afflicted these brothers, but if they came from poorer families, they likely died before the disease had a chance to impact and imprint on the bones as heavily.

The likely prospect of these brothers being the victims of leprosy is indeed intriguing: If proven true, this would constitute one of the earliest examples of leprosy ever found in the world. Work is ongoing to determine if this is, in fact, the disease that the brothers suffered from.

Given how the circa 15th-century b.c.e. dating of these Canaanite burials is proximate to the biblical chronology for the Exodus (within the same century), this squares well with several biblical passages discussing the problem of leprosy and how to isolate and deal with such a disease (i.e. Leviticus 13-14, Deuteronomy 24:8). Classical accounts of the Exodus also describe leprosy as being rampant at this period in time.

Megiddo itself was a powerful, populated Canaanite city prior to the Israelite arrival (and following, as well; despite the king of Megiddo having been killed during the conquest of Canaan, the city continued to be occupied by Canaanites—Judges 1:27). Evidently, it was a city advanced enough to be conducting such risky brain surgeries.

This same practice of trephination was also known in Egypt, from which the Israelites departed. Interestingly, against the backdrop of this period in the biblical account is a theme repeatedly emphasized: reliance on God for healing, “for I am the Lord that healeth thee” (Exodus 15:26). Though many questions remain about these Megiddo individuals, one thing is for sure: They relied on the prescribed medicine of the day, and although they may have lived a little longer than the poorer individuals of the city, the surgical intervention did little to help “heal” the disease.