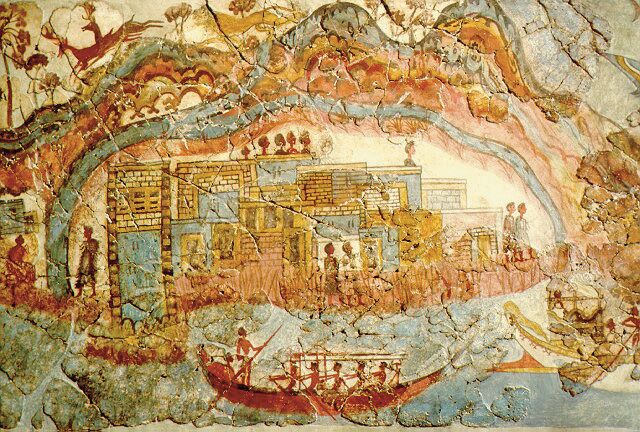

The Minoans are history’s great mystery civilization. They were a colorful polity centered on the Mediterranean island of Crete, with ornate architecture, rich produce and trade, dramatic artwork, and peculiar pictographic scripts that still have yet to be deciphered.

The civilization flourished in the early second millennium b.c.e., but sometime around the 15th century, began to fall apart. By the 12th century b.c.e., it had disappeared.

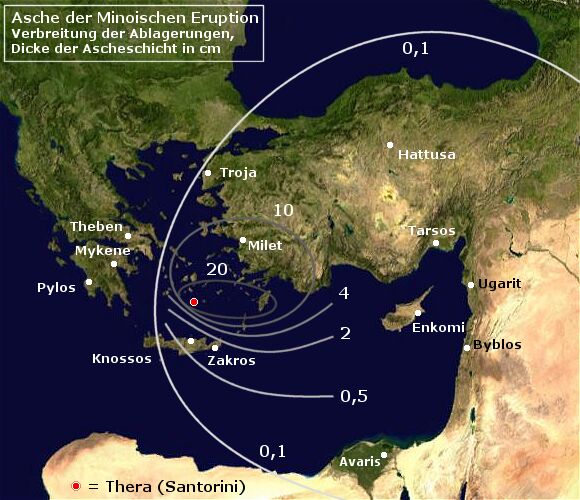

What happened to the Minoan civilization remains hotly debated. Its fall (or at least the start of the civilizational collapse) is typically attributed to the Thera eruption around 1600 b.c.e. Thera’s eruption (a volcanic island more commonly known today as Santorini, once a Minoan outpost due north of Crete) was one of the largest eruptions in human history.

Despite the savagery of this natural disaster, any record of it in surrounding histories remains uncertain. Does the Bible have any hint at these events—the Thera eruption or the downfall of the Minoan civilization? The stock answer is, typically, No—but certain verses contain more than meets the eye.

Identifying Crete

First, of course, Crete must be identified. The name found in the Bible, identified with the island of Crete, is the “isle of Caphtor” (Jeremiah 47:4; see also Genesis 10:14; Deuteronomy 2:23; Amos 9:7; 1 Chronicles 1:12). This identification is in parallel to 18th-century b.c.e. references to Crete in the Mari texts as Kaptara, a similar name in Assyrian records, and Egyptian references to the island as Keftiu.

The inference is that this was the original Minoan name of the island. The Mycenaean Greeks, who displaced and occupied the island from the end of the second millennium b.c.e. onward, are responsible for the more modern name Crete—Mycenaean Greek “Linear B” texts going back to the 1400s b.c.e. refer to the island as Kerete (the modern name pronounced “Kriti”).

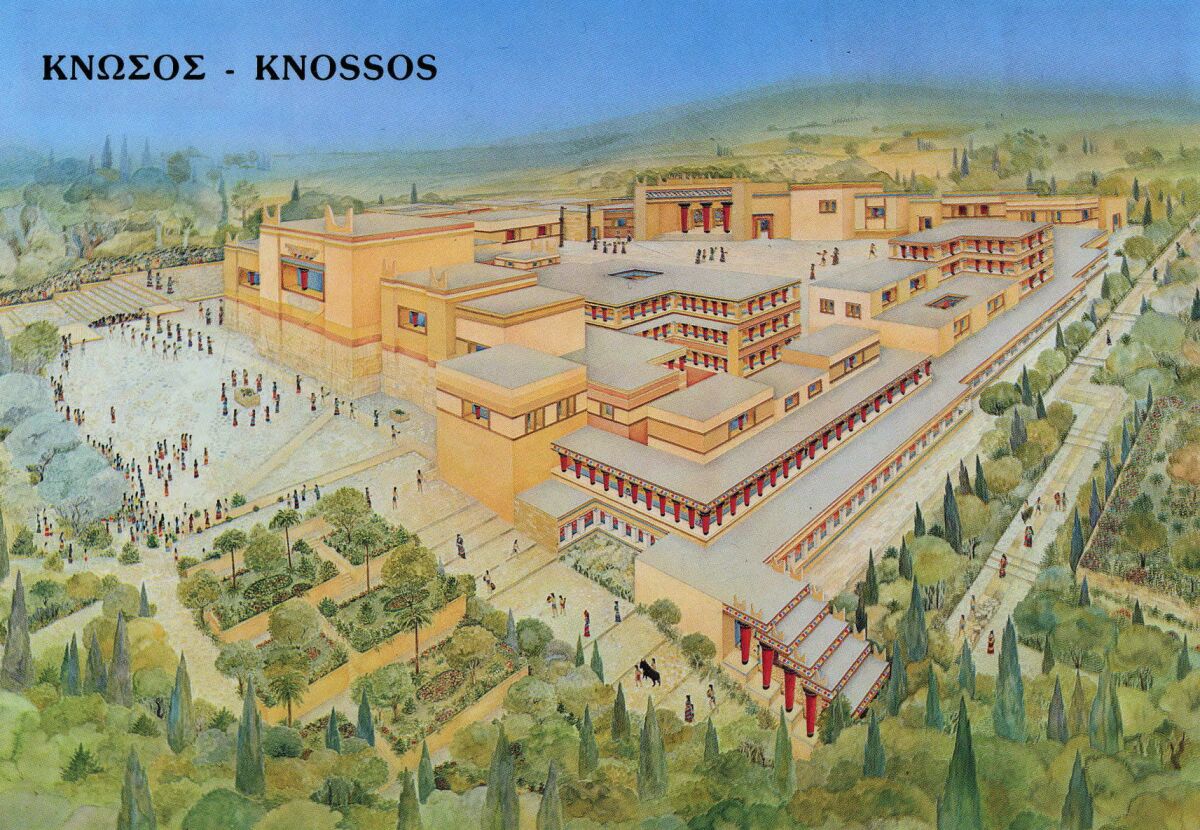

While the meaning of the name Caphtor is not certain, it appears quite apropos for the Minoan civilization, based on another Hebrew word spelled exactly the same way and used in the same early contexts paralleling the Minoan civilization (namely, in the book of Exodus). The word caphtor is used to refer to bulb-like pillar capitals or similar objects. And to this day, one of the most famous attributes of the ancient Minoan civilization is their very distinctive pillars, topped by unique bulb-like capitals.

But can we get any idea from the Bible about what happened to the Minoans, or Caphtorites?

Thera Eruption?

Throughout recent history, there has been some attempt to connect the Thera eruption with the Exodus plagues account. Attempts to link the two include explaining the ninth plague, the “day turning to night,” as a result of the eruption; some even linking the account of the Israelites being led in the wilderness by a “cloud by day” and a “pillar of fire by night” as a reference to the eruption.

Clearly, though, such references are a stretch and are made with the view that the biblical Exodus account was imagined long after the events described, based loosely on the haziest of memories—thus, turning a simple eruption into a rather convoluted plagues-and-redemption story.

The dating of the eruption is hotly contested. (This is an interesting subject in itself, as many modern archaeologists swear by carbon dating as a be-all-end-all—yet when carbon dates emerged for Santorini’s eruption, pointing it to occurring around 1650 b.c.e., it was furiously contested by archaeologists, who had dated the event to 1550 b.c.e.) Nevertheless, the earliest date of the eruption is a century prior to the clear biblical chronological date of the Exodus plagues—two centuries prior, at the other end of the spectrum.

As such, it relates to the period in which the Israelites were still in Egypt. This, of itself, would explain a lack of mention in the biblical account, especially if it was within the period of Israelite slavery.

Yet indication of the massive eruption may be sought at the very start of this period, in the entrance of Jacob’s family into Egypt—a migration that took place, according to the standard “short-sojourn” chronology, during the 17th century b.c.e. Recall the account of Joseph’s dream while in Egypt—that the land would experience seven years of plenty, followed suddenly by seven years of abject famine. According to the chronology, this would have taken place in the first half- to middle-17th century.

The Bible relates that this peculiar famine affected not only Egypt but also the surrounding regions. The Levant, including Canaan, was hit particularly hard (this is why Jacob sent his sons into Egypt to gather food). “And the seven years of famine began to come, according as Joseph had said; and there was famine in all lands; but in all the land of Egypt there was bread” (Genesis 41:54; courtesy of Joseph’s preparation of storehouses, during the seven years of plenty). “And the famine was over all the face of the earth …. [T]he famine was sore in all the earth” (verses 56-57).

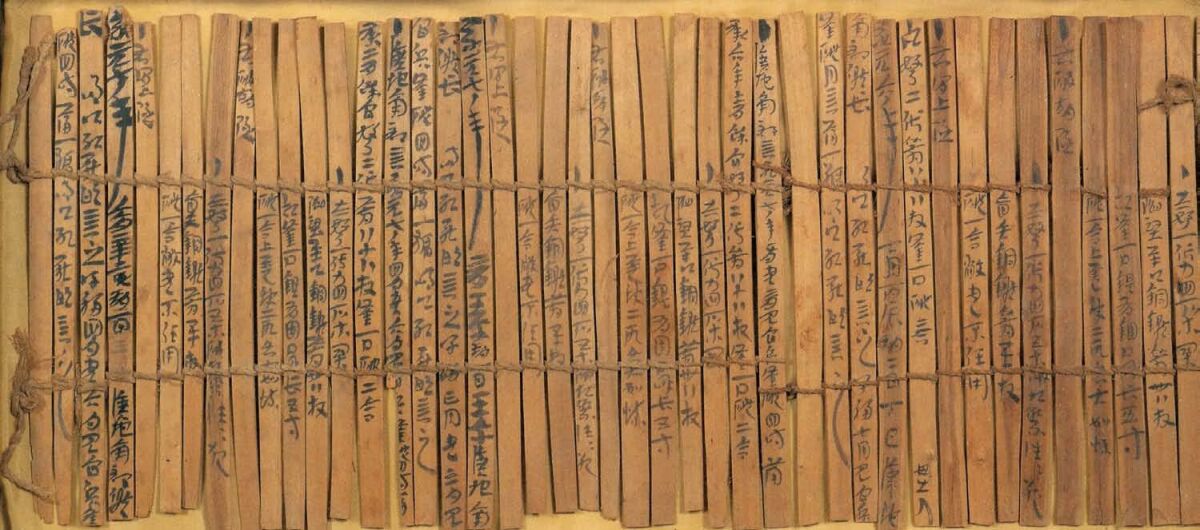

What better cause of such a famine than the fallout of one of the worst eruptions in human history? After all, researchers point to the Bamboo Annals of China, likewise identifying a 17th-century b.c.e. collapse of the Xia dynasty, due to events that included “yellow fog, a dim sun, then three suns, frost in July, famine and the withering of all five cereals.”

Note, again, that the early carbon dating of the Thera eruption to sometime around the middle of the 17th century would be a potential fit for the low chronology of this famine account. Note also that the pharaoh’s vision of this famine included corn being “blasted [or scorched] with the east wind” (Genesis 41:6).

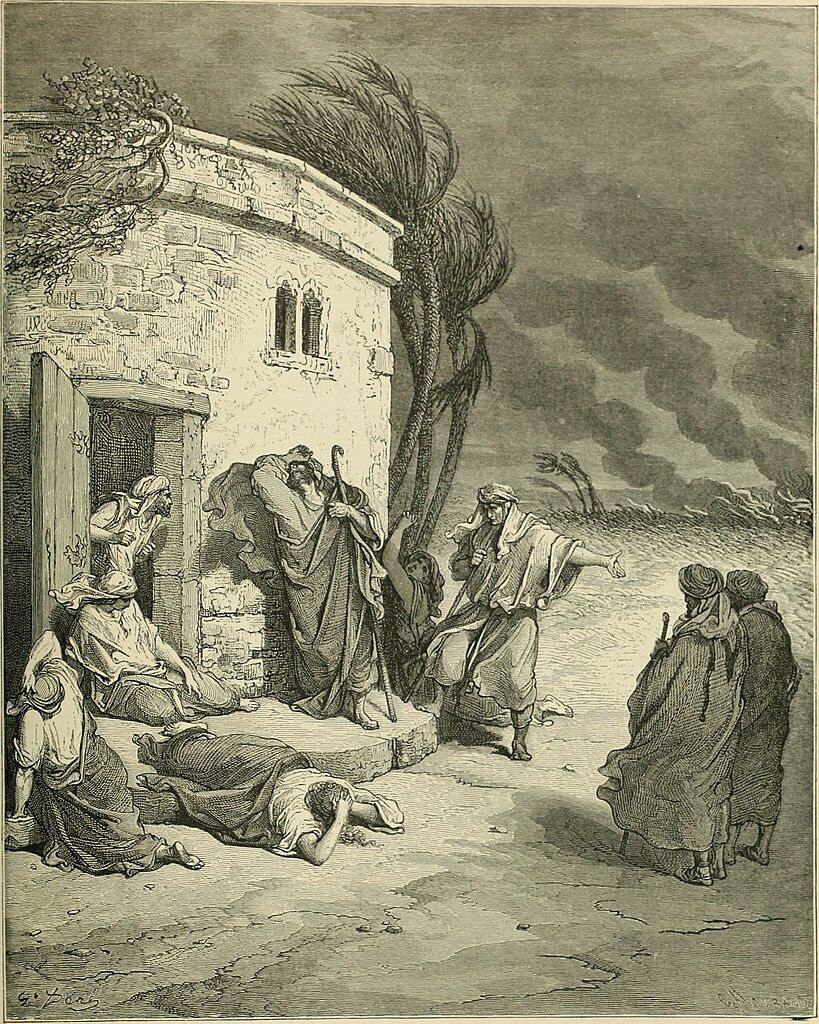

Another possible link may be with the book of Job. Some identify Job as the son of Issachar (Genesis 46:13), which would likewise put him around this general time period (though the Hebrew names are spelled slightly differently, and there is no mention of Issachar or any Israelites in his book). That aside, based on the identity of certain of Job’s friends (Eliphaz as son of Esau, Bildad as descendant of Abraham’s son Shuah, and the young Elihu, descendant of Abraham’s brother Nahor)—and given that Job was already an older man with 10 grown children—this could put us firmly within the time frame of the Thera eruption.

This link, then, may add further context to mention in the book of Job of “fire … fallen from heaven” (Job 1:16), a “great wind” that tore apart Job’s children’s house (verse 19), and Job’s sitting “among the ashes” (Job 2:8, 42:6; note that Crete became blanketed in ash that blew southward from Thera/Santorini, depicted below).

What Happened to the Minoans?

The Thera eruption certainly helps to explain what triggered the downfall of the Minoan civilization. But does the Bible have anything more to say about this people? It certainly does.

From the 13th century b.c.e. onward, in the archaeological (and biblical) record, we start to see a demographic change in the western Levant: the arrival of a Mediterranean people that took on the name Philistines. (The name is briefly ascribed to earlier inhabitants of this land in earlier Bible chapters; however, the book of Judges reveals that a primary influx occurred during the last half of the second millennium b.c.e., reaching critical mass at the end of that period—famously, the time of Samson, when the Philistines dominated the Israelites. And here again, there is an emphasis in the Bible and archaeology on uniquely pillared Philistine buildings.)

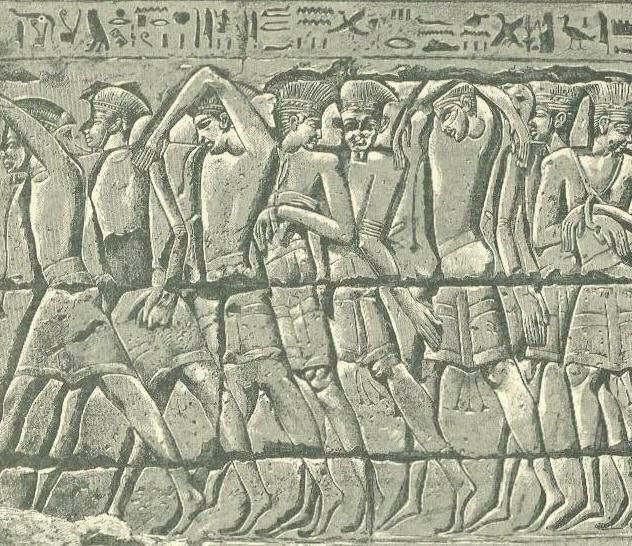

And where does the Bible ascribe the point of origin for these Philistines? “Have not I brought up Israel out of the land of Egypt, And the Philistines from Caphtor …?”(Amos 9:7). Deuteronomy 2:23 relates this migration into the coast of Canaan. “[T]he Caphtorim, that came forth out of Caphtor, destroyed them [the inhabitants of the region of Philistia], and dwelt in their stead.” Twelfth-century b.c.e. Egyptian records likewise describe the settling of “Peleset” people from the Mediterranean into the land of Philistia.

And as of 2019, dna research has confirmed the same. Studies on the bones of bodies unearthed at the Philistine site of Ashkelon have revealed a massive population shift, beginning in the 13th century b.c.e., with the influx of a Mediterranean people who genetically fit most closely to an origin from Crete (genetically labeled “Bronze Age Crete_Odigitria_BA”).

Another Cretan Population in Israel?

The Caphtorim, however, aren’t the only people in the Bible associated with the island of Crete. Enter the Cherethim.

The name translated Cherethite is actually Krete in the original Hebrew—a perfect match for the Mycenaean Greek name and people of Crete (Kerete, modern Greek Krete). As such, Cherethites are considered to be a Cretan people, mentioned in conjunction with the Philistines (and the Hebrew name for this people is the same modern Hebrew name for the island of Crete today). Of them, Zephaniah 2:5 mentions “the inhabitants of the sea-coast [or, sea-territory], The nation of the Cherethites.” (The same verse also mentions the Philistines.)

The Cherethites, however, are unique from the general body of Philistines, in that they made up a formidable mercenary fighting unit within King David’s forces, and were originally remarkably faithful servants of David, Solomon, Benaiah and Zadok, even in times of national upheaval for Israel (e.g. 2 Samuel 8:18; 15:18; 20:23; 1 Kings 1:38). It’s also notable that the earliest mention of this people is from the 11th century b.c.e. onward—the time of the Mycenaean Greek population of Crete, and their use of this name. It stands to reason that David’s Cherethites were Mycenaean Greeks from Crete.

And here we arrive at a fascinating biblical tidbit pointing to a reason for the arrival of immigrants from Crete.

‘Survivors’

Jeremiah was a prophet on the scene during the seventh to sixth centuries b.c.e. Chapter 47 of his book contains a prophecy against the Philistines—and a notable hint at a past tragedy.

“Because of the day that cometh To spoil all the Philistines, To cut off from Tyre and Zidon Every helper that remaineth; For the Lord will spoil the Philistines, The remnant of the isle of Caphtor” (verse 4).

The Hebrew word “remnant” means just that—remnant, residue, rest, what is left, remainder, also survivors. As such, the verse could be translated, “the Philistine survivors of the isle of Crete.” This would certainly help illustrate the scope of catastrophe on the island during the middle-second millennium b.c.e.

The sixth-century b.c.e. Prophet Ezekiel likewise carries a condemnation for the Philistines and includes similar language, tying together geographically both the Philistines and the Cherethites. “Thus saith the Lord God: Because the Philistines have dealt by revenge, and have taken vengeance with disdain of soul to destroy, for the old hatred; therefore thus saith the Lord God: Behold, I will stretch out My hand upon the Philistines, and I will cut off the Cherethites, and destroy the remnant of the sea-coast” (Ezekiel 25:15-16).

And what could have been the “old hatred” of the original inhabitants of Crete? We are left to wonder. But the inference could be that the Cretan remnant’s latter “destruction,” coming from God for their hatred and revenge against Israel, followed that of an original destruction, “for the old hatred.” Could this be a reference to the fiery destruction caused by the Thera eruption and the end of the Minoan civilization? “And I will execute great vengeance upon them with furious rebukes; and they shall know that I am the Lord, when I shall lay My vengeance upon them” (verse 17).

Bible history primarily concerns itself with Israel. Yet within it are remarkable insights into wider populations, international relations, upheavals and calamities. Crete is no exception—and the impressive ruins of palaces like Knossos stand testament to a period of grand Mediterranean opulence that came crashing down.

And while the Mycenaean-to-modern Greeks have exhibited, at times, their own share of “the old hatred,” anti-Semitism, there have likewise been periods of selfless friendship and service—there remains a devoted Jewish community in Greece, and the Greek military stands in close partnership with Israel, often training alongside Israel’s, in a partnership that hearkens back to King David and the Cherethites.

And throughout history (particularly during the recent, brutal occupation of Crete by Nazi Germany in World War ii), the ruggedly beautiful terrain of Crete has become a place for survivors.