If you’ve ever walked through Hezekiah’s tunnel, perhaps you’ve wondered if there’s any purpose linked to the dramatically higher ceiling height at the southern end of the tunnel. Or perhaps you’ve wondered why, when the tunnel’s water is less than knee-deep, there is an occasionally visible “waterline” high up along the walls of the tunnel. Perhaps you’ve also wondered about the implications of Hezekiah channeling water away from the Gihon Spring reservoir complex—wouldn’t the subsequently lowered water level deprive the important upper city of easy access to water?

Those questions have been answered, at least in part, through a fascinating new research project published in April in the academic journal Archaeological Discovery. In an article titled “A Sluice Gate in Hezekiah’s (Iron Age ii) Aqueduct in Jerusalem: Archaeology, Architecture and the Petrochemical Setting of Its Micro and Macro Structures,” authors Aryeh E. Shimron, Vitaly Gutkin and Vladimir Uvarov—researchers from the Geological Survey of Israel and Hebrew University’s Center for Nanoscience and Nanotechnology—revealed new evidence they believe shows that Hezekiah’s tunnel contained an ingenious sluice gate through which water levels could be controlled.

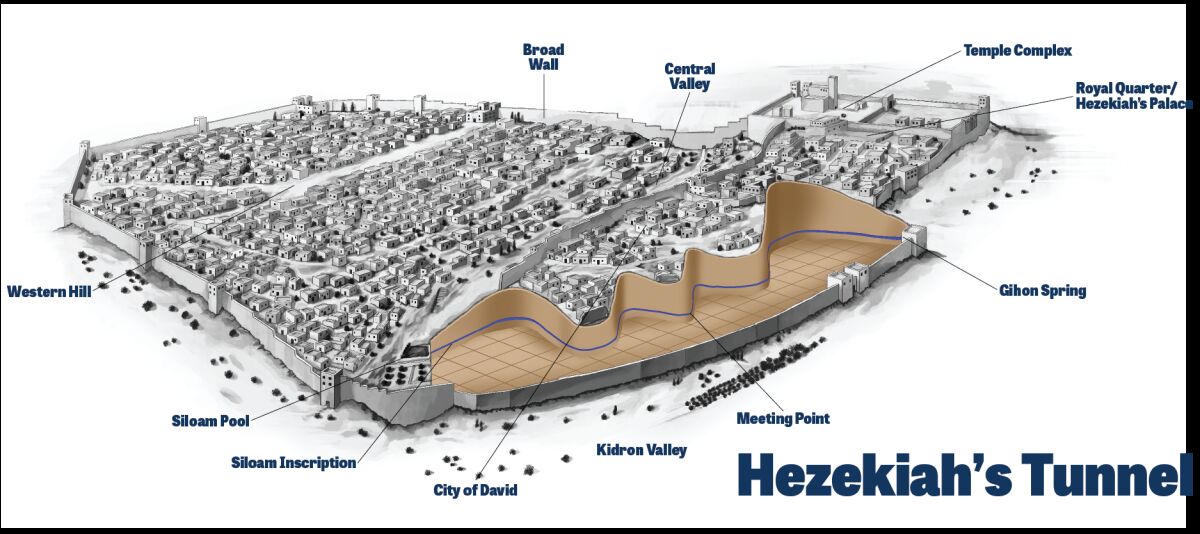

The biblical overview of Hezekiah’s tunnel, including the reason for its construction, is fairly well established. Constructed at the end of the eighth century b.c.e., it was intended at the time of Assyrian king Sennacherib’s invasion as a precautionary divergence of the Gihon Spring water from the more vulnerable eastern side of the city down through the bedrock of Jerusalem to the Siloam pool catchment area in the lower southern part of the city. 2 Chronicles 32 reads: “And when Hezekiah saw that Sennacherib was come, and that he was purposed to fight against Jerusalem, he took counsel with his princes and his mighty men to stop the waters of the fountains which were without the city; and they helped him. So there was gathered much people together, and they stopped all the fountains, and the brook that flowed through the midst of the land, saying: ‘Why should the kings of Assyria come, and find much water?’” (verses 2-4). Verse 30 of the same chapter reads: “This same Hezekiah also stopped the upper watercourse of Gihon, and brought it straight down to the west side of the city of David. And Hezekiah prospered in all his works” (King James Version).

The 533-meter-long Siloam Tunnel (as it is sometimes called), channeled through from both ends, was no mean feat for the hewers. But besides the remarkable, easily observable features of the tunnel—not just the incredible length, but also the remarkably gentle overall gradient of just 0.06 degrees (the exit point is only 30 centimeters lower than the origin)—this was also no mere hole through bedrock. That’s where the new research comes into play.

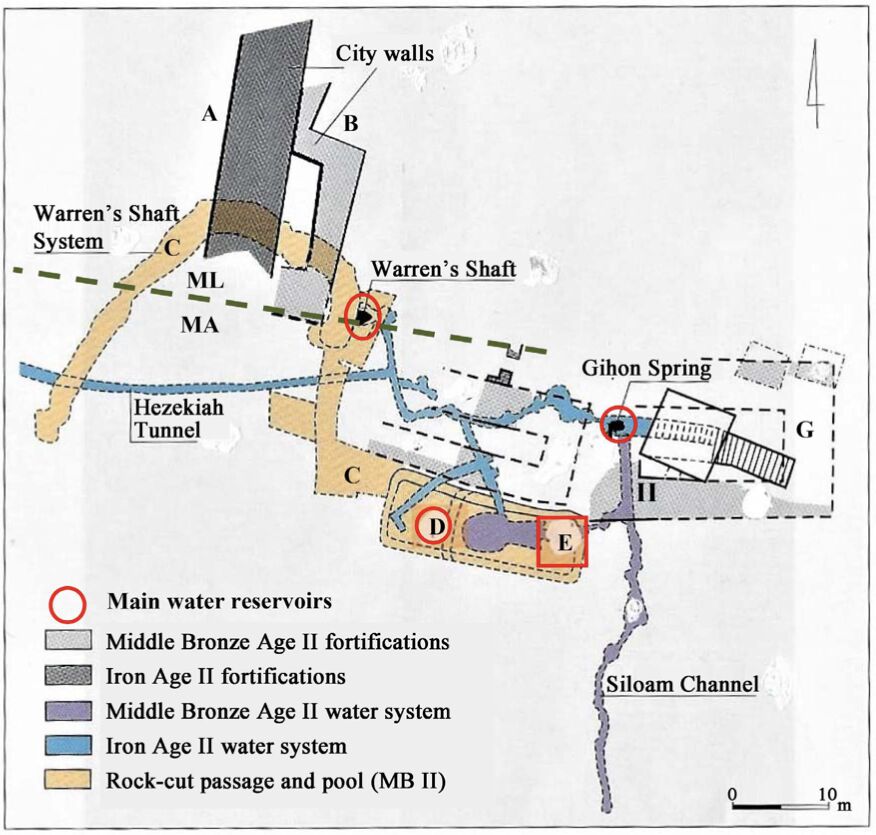

One of the chief issues raised by the authors of the above academic paper is that the diversion of the Gihon Spring water through Hezekiah’s tunnel would lower the water level so significantly that the spring would no longer be able to fill the existing upper Gihon catchment area, which is fed by a cavern conduit located 2.4 meters above the mouth of the spring. The redirection of water through the tunnel would make the water level so low in the upper part of the city as to render it virtually inaccessible. “In the absence of the frequently erratic ebb and flow (pulsating) nature of the spring this elevation would not suffice for the water to enter Channels ii, the Rock-cut Pool and fill the WS [Warren’s Shaft] cave to a minimum level for drawing water,” they write. As such, rather than Hezekiah’s tunnel fully solving a problem, it would have created a new one—the new tunnel essentially cutting off easy water access through Warren’s Shaft for the vital upper side of the city, where such critical infrastructure as the palace and the temple was situated.

The answer to this question has proved problematic over the past century of research relating to Hezekiah’s tunnel. The authors cited one solution presented by geologist Dr. Dan Gill in 1994, who wrote that in order for water to still be readily accessible from the infrastructure around the mouth of the Gihon Spring, “a dam must have been constructed somewhere along Hezekiah’s tunnel,” allowing the water level to rise sufficiently to fill the original raised catchment complex above the spring.

Clearly, the idea of going to all the effort to excavate Hezekiah’s tunnel (and at such a precise gradient) only to dam it up seems counterintuitive. This, therefore, could not have been any ordinary dam.

The new research paper takes this theory much further. Shimron, Gutkin and Uvarov write: “We have searched for such a dam at what would be the ideal, perhaps only location for such a structure to be able to function effectively, and have found physical evidence for what may have been a movable blocking wall (sluice) at precisely such a place. … [This] ‘device’ to control water level in the new aqueduct and thereby also the spring environ was designed and eventually constructed about 71 m from the tunnel’s southern exit.”

A sluice gate is typically a wood or metal sliding barrier, set into grooves on the side walls of a waterway, that can be raised or lowered to control the flow of water through a passage. Placing a sufficiently sealing sluice gate at some point within the tunnel would have allowed the water level to rise high enough to fill the raised, upper catchment system around the mouth of the Gihon Spring; the sluice would have also allowed a degree of selective control over water levels for the upper and lower parts of the city. If one part of the city or the other needed a greater supply of water, levels could be adjusted accordingly with the sluice gate. This degree of control would have proved helpful in a siege situation, granting the capability of selectively cutting off easy access to water, depending on the situation.

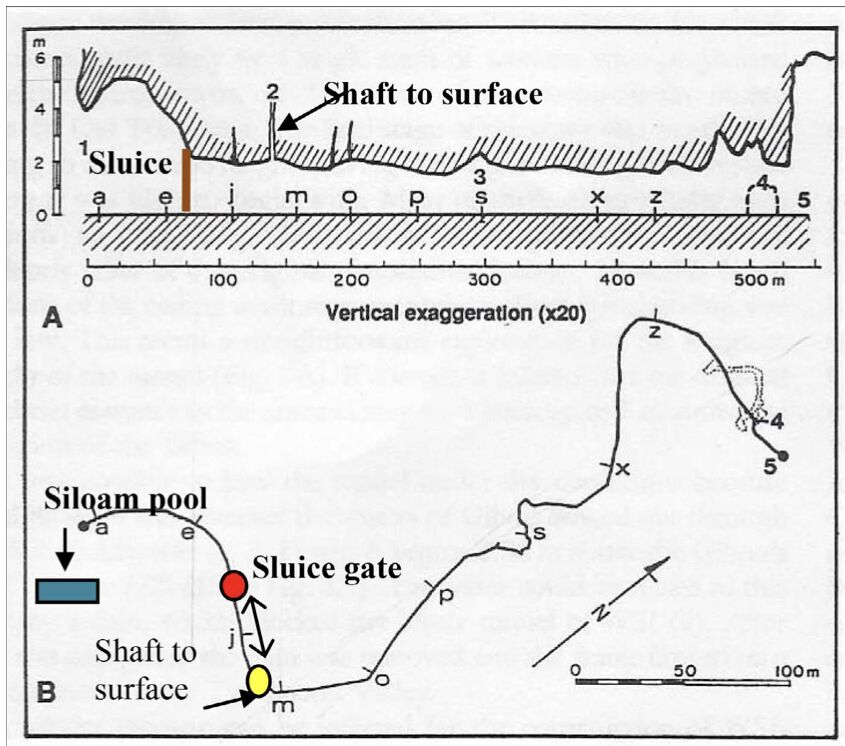

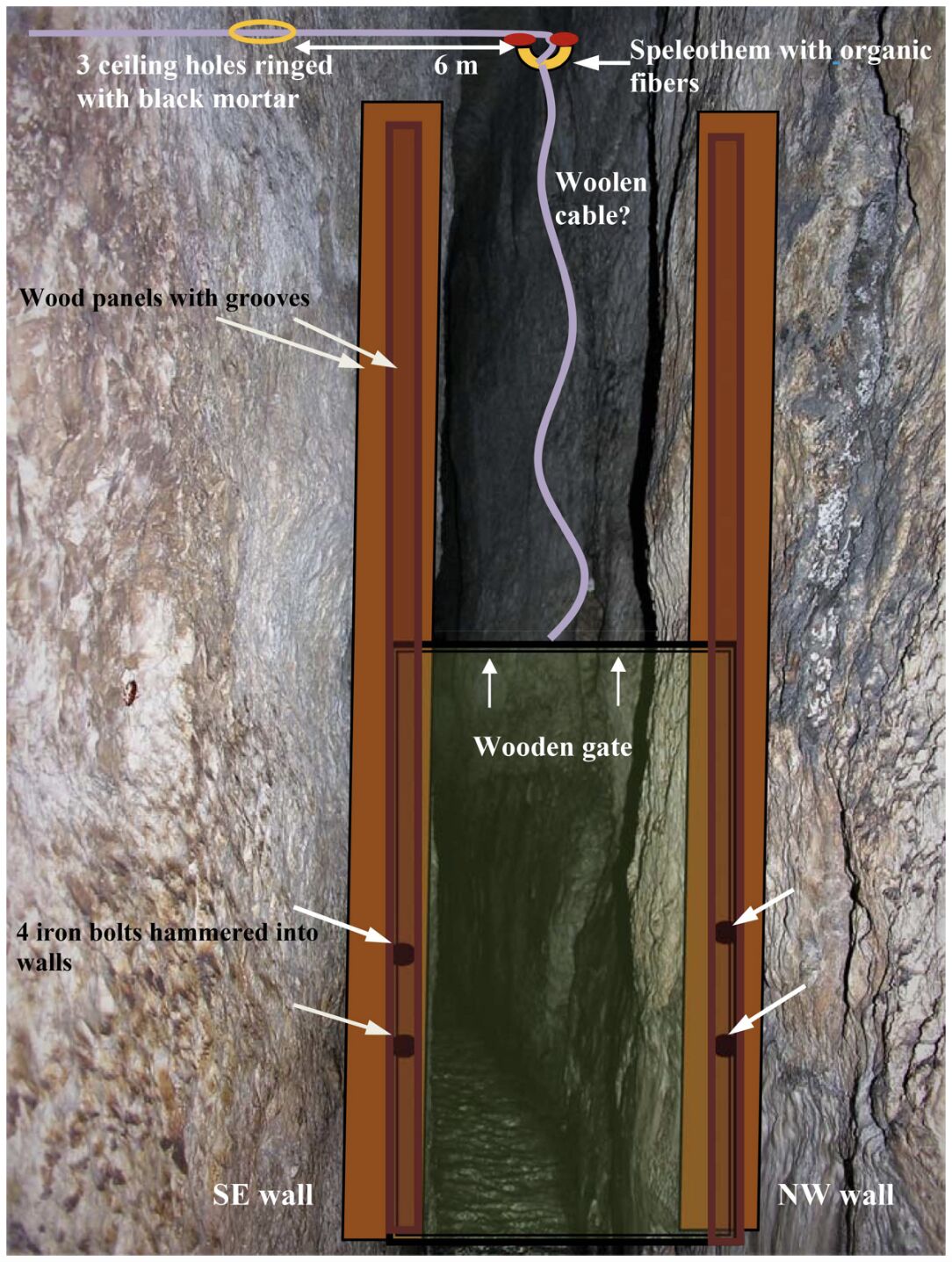

The Archaeological Discovery article revealed several compelling proofs for the presence of this original sluice gate within the tunnel. Chief among them is the discovery of four 8-cm-long iron bolts/nails sunken into the bedrock walls of the tunnel, 71 meters from the tunnel’s exit. The badly corroded bolts are symmetrically placed, two on each side of the tunnel’s walls. They were found to have traces of petrified wood (almost certainly cedar), so they evidently secured some kind of wooden frame within the tunnel anciently. Interestingly, it is also at this point in the tunnel that the ceiling is elevated significantly higher. This height would have been necessary in order to sufficiently house the tall, vertically-sliding gate.

But how to properly control such a device? The researchers point out another unique feature not far from this spot in the tunnel: a narrow shaft that extends from the tunnel ceiling (see image above, right) through to an accessible subterranean passage (known as Channel ii) and out to the surface. Through this narrow “Shaft to Surface,” they posit, the sluice gate was operated by a rope system. And sure enough, in the plaster material of this part of the tunnel ceiling, calcified wool fibres were discovered, evidently from the use of just such a rope. There is also a significant amount of blackened mortar with traces of smelting ore on the ceiling directly above the location of the sluice frame, which evidently secured some form of device (since lost) through which the sluice gate rope is believed to have passed. This narrow surface shaft, through which the sluice gate rope is believed to have been controlled, was independently accessible from above, within the subterranean Channel ii. This sheltered channel would have given the operators secure control over the spring waters, particularly under siege conditions.

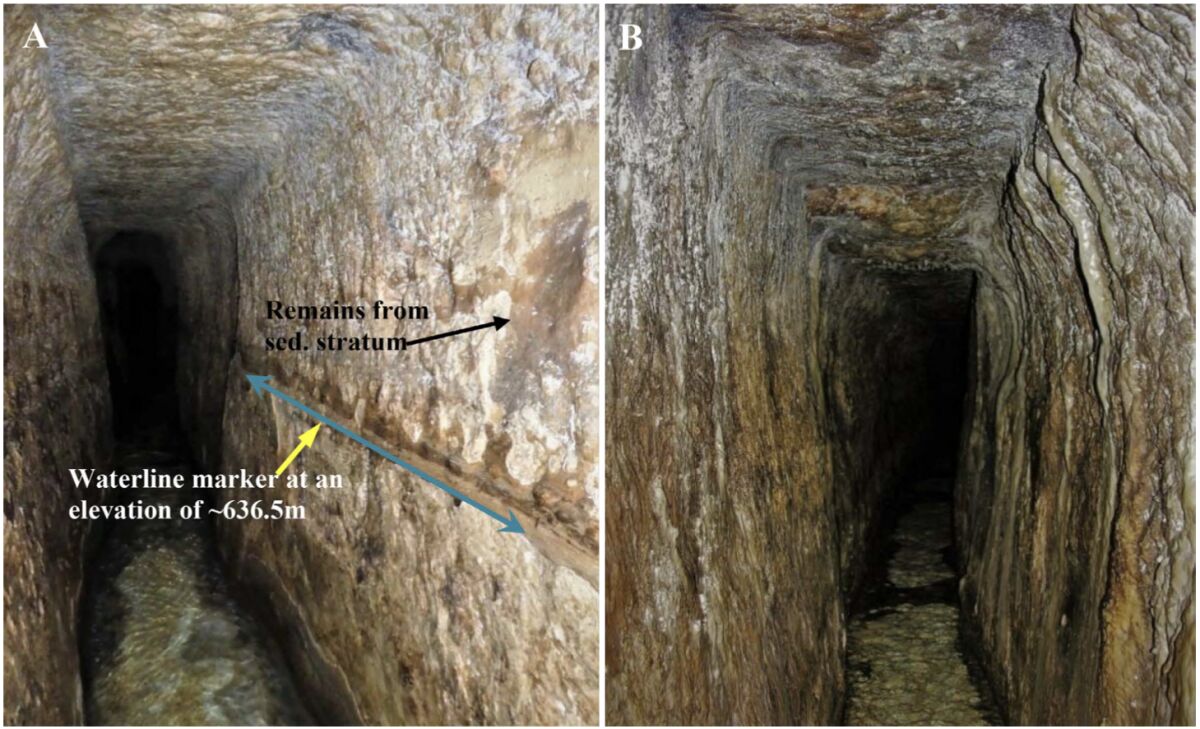

Additional evidence of the presence of the sluice gate can be seen along the walls of Hezekiah’s tunnel: Horizontal silty and muddy staining is present along the tunnel walls, with a “dominant waterline” 1.5 meters high—showing that the water was at one time consistently dammed to this regulated height within the tunnel.

On this point, Shimron, Gutkin and Uvarov noted the importance the tunnel engineers placed on sealing gaps and cracks in the bedrock leading up to the sluice gate, pointing out the heavy use of hydraulic plaster carbon-dated to the eighth century b.c.e. This, together with the dating of the fine sedimental laminae along the tunnel walls, “indicate[s] that some of the most pronounced and highest watermark levels were deposited between the eighth and fourth centuries b.c.e., thereby confirming water level control already during this period.”

“The construction of the sluice gate and the application of plaster along the full length of the tunnel would have required a dry tunnel for carrying out this task. The most convenient time for this would have been prior to allowing water flow south towards the Siloam Pool—that is during Iron Age ii,” they write.

Finally, the authors noted that not only would this structure have been a significant innovation of its own right, but it would also constitute “to the best of our knowledge, the oldest sluice gate known.” As they point out:

To the best of our knowledge no sluice gates have been recorded that predate the Roman ~1-2nd century c.e. Period. The oldest Iron Age structures referred to as sluice gates were found in the Judean Desert (Stager, 1976). Constructed to raise the level of water behind a stationary stone dam, these structures are weirs rather than sluice gates. Consequently, if Hezekiah’s Tunnel sluice ever functioned as a movable blocking wall, it may well be the oldest sluice gate on record.

Such an innovation would hardly be surprising for the likes of the Jewish nation, however—whether in modern times or anciently. Note the biblical description of Jerusalem’s “inventors” from the very same century, during the reign of Uzziah: “And he made in Jerusalem engines, invented by skilful men, to be on the towers and upon the corners …” (2 Chronicles 26:15). The new research, then, only adds a new layer of intrigue to the already incredible engineering feat that is Hezekiah’s Tunnel.

And the rest of the acts of Hezekiah, and all his might, and how he made a pool, and a conduit, and brought water into the city, are they not written in the book of the chronicles of the kings of Judah? (2 Kings 20:20)