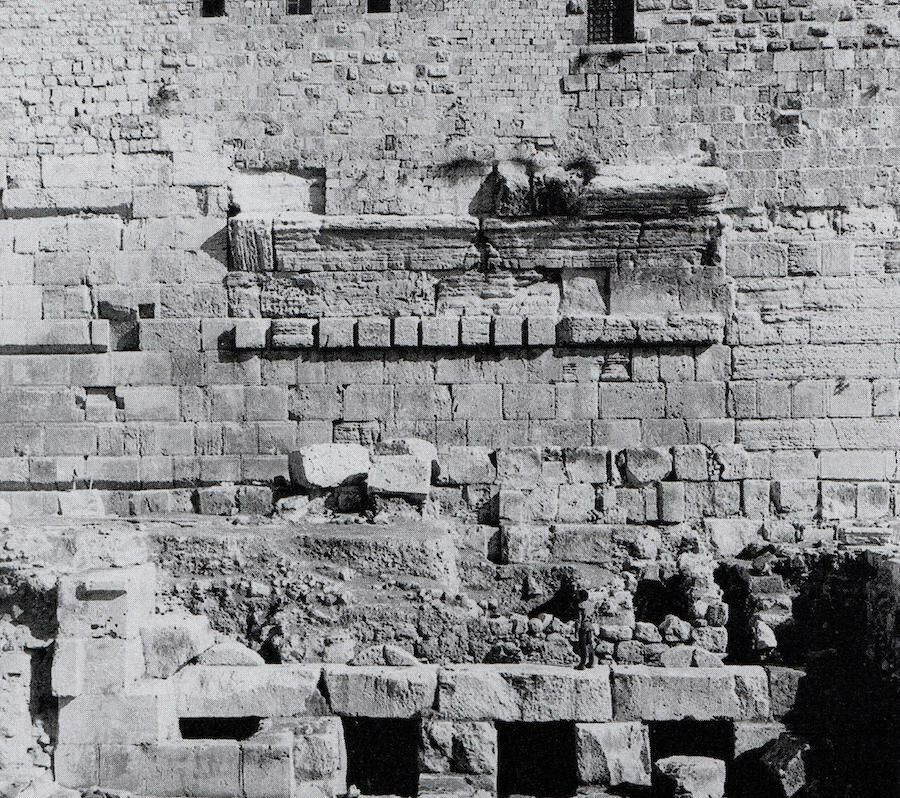

One of Jerusalem’s most iconic archaeological images is Robinson’s Arch. Named for Bible scholar Edward Robinson, who observed it in 1838, it is the ruin of what would have been a great stone landmark well-known to the Jews and Romans of 2,000 years ago.

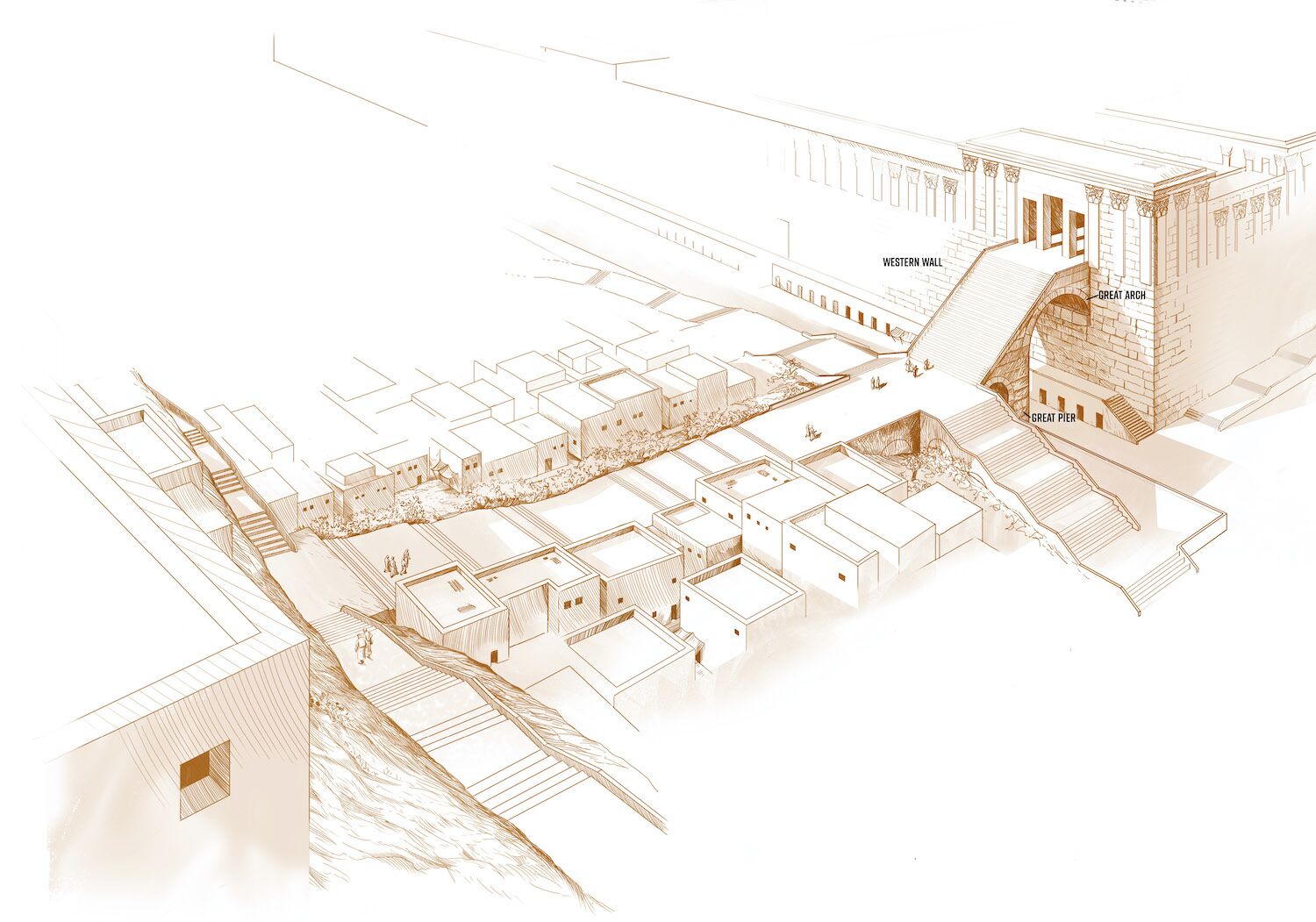

The conspicuous remnant of this 15-meter-wide archway springing from 20 meters up the Western Wall of the Temple Mount has led to all manner of conclusions about its purpose. At first it was thought to be part of a bridge connecting the southern portion of the Temple Mount to the aristocratic upper city on the hill to the west. Later it was thought to be part of a monumental right-angled staircase that turned south and led toward the City of David. Later still it was thought to be part of a two-way staircase that turned both to the south and to the north.

Now, Jerusalem archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar has a new theory: Instead of a one-way or a two-way staircase imagined by excavators, the arch was part of a monumental four-way staircase, a structure completely unique among ancient classical architecture. You can read documentation of this amazing interpretation in her recently published book, Over the Crossroads of Time: Jerusalem’s Temple Mount Monumental Staircases.

Dr. Mazar’s discovery has been a long time in the making.

Three decades after Robinson documented the remnant of the arch, an artistic representation shows a man standing right next to the arch.

Today, the arch is high above ground level. This is mainly due to massive archaeological excavations undertaken from 1968 to 1978 by Dr. Mazar’s grandfather, Prof. Benjamin Mazar of Hebrew University. The “Big Dig” Temple Mount excavations, which continued year-round for a decade, first focused on the area directly beneath Robinson’s Arch. What Professor Mazar discovered there were massive cut stones laying on a street built during the first half of the first century c.e. They had fallen from the Western Wall during the c.e. 70 destruction of Jerusalem.

A few meters to the east, just across that same street, Professor Mazar’s team of excavators—and Eilat, only 13 at the time—uncovered stone doorways. These would have been entrances to shops that lined the street opposite the Western Wall. The shops were incorporated into the chambers of a massive 3.8-meter-wide, 15-meter-long stone pier. Artifacts related to the pier revealed that it had been built by none other than Herod the Great. Professor Mazar had located the foundation for the other side of Robinson’s Arch.

Further excavations by Professor Mazar revealed that the pier connected to a structure with a series of vaults running perpendicular to the direction of the arch. He determined that, similar to Robinson’s arch itself, these vaults formed the foundation to an overhead walkway. And as these vaults generally descended in height toward the south, they had discovered the remains of a staircase that made a right-angled turn.

This understanding of the structure remained largely accepted for decades: the huge staircase descended westward, then turned southward (although Mazar’s architect, Brian Lalor, suspected that an additional staircase turned northward).

After Professor Mazar’s death in 1995, his granddaughter took up the mantle and continued preparing his work for final scientific publication. Five volumes of The Temple Mount Excavations in Jerusalem have been published so far in Hebrew University’s qedem series. Poring over her grandfather’s 50-year-old field documentation forced Dr. Eilat Mazar to reexamine the arch structure. And she was surprised by what she found.

“As we learned, this structure, believed by Benjamin Mazar to be a monumental staircase with a 90-degree turn to the south, is actually a much more elaborate staircase,” she writes in her new book. “With four turns—not the one suggested by B. Mazar—this was a Four-Way Monumental Staircase, unique among the structures of the classical world.”

Critical to this change in understanding was the reexamination of the gradated vaults that supported the staircase and the realization that the remains of those vaults actually lead in four different directions from the initial descent.

According to Mazar, construction of the monumental staircase took place at the same time as the Temple Mount and was part of King Herod’s master plan. According to first-century Jewish historian Josephus, construction on the Temple Mount began in the 18th year of Herod’s reign and continued until his death (19 to 4 b.c.e.). Afterward, construction slowed considerably, and the staircase and associated street and plaza were not fully functional until 40 years later.

Based on numerous coins discovered inside the structure, Dr. Mazar concludes, “With the completion of the Four-Way Monumental Staircase, the spaces inside its vaults and surroundings were left undeveloped as a rocky area until the rule of Pontius Pilatus/Agrippa i (c.e. 26–44).”

This means that the inhabitants of Jerusalem had only a generation or two to see and use this grand structure before it was destroyed in c.e. 70 and commenced its 2,000-year wait for someone to put together all the pieces.

To learn more, read Dr. Mazar’s latest book: Over the Crossroads of Time: Jerusalem’s Temple Mount Monumental Staircases.