Did you know that the righteous kings of Israel who sat on the throne of King David were all buried in a massive tomb along with David and Solomon? The Bible makes several references to “the sepulchres of the kings.” These sepulchers are probably rooms inside one large tomb.

At the time of Nehemiah and the reconstruction of Jerusalem in the fifth century b.c.e., these tombs were apparently still a well-known fixture within the city. In the first century c.e., the New Testament apostle Peter stated that the location of David’s sepulcher was common knowledge.

Historians have recorded incidents of people trying to get into those tombs—and succeeding, to a point, on a couple of occasions. However, in one instance in the first century b.c.e., when two men tried to enter the tombs further, they were struck dead. That caused so much fear that nobody again attempted to enter these tombs.

Is it possible that God did not want those tombs opened at that time?

Amazingly, Scripture indicates that the tombs of the kings will be uncovered eventually. What makes it especially interesting is the fact that there is so much evidence within Scripture indicating where this grand sepulcher is. Every indication is those tombs are right under David’s palace, or very close to it.

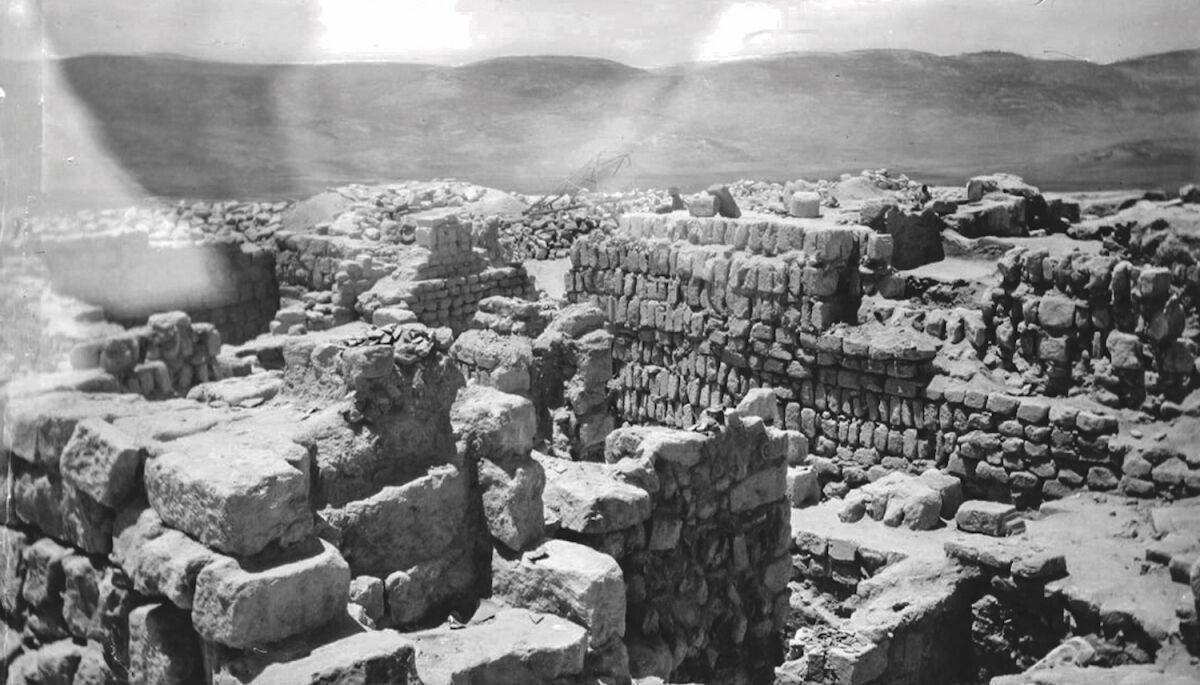

And in 2005, a small part of David’s palace was discovered. Might the tombs of the kings be another spectacular find that archaeologists will uncover in the near future?

Where Is David’s Tomb?

Where was David buried? The Bible provides a lot of evidence to answer.

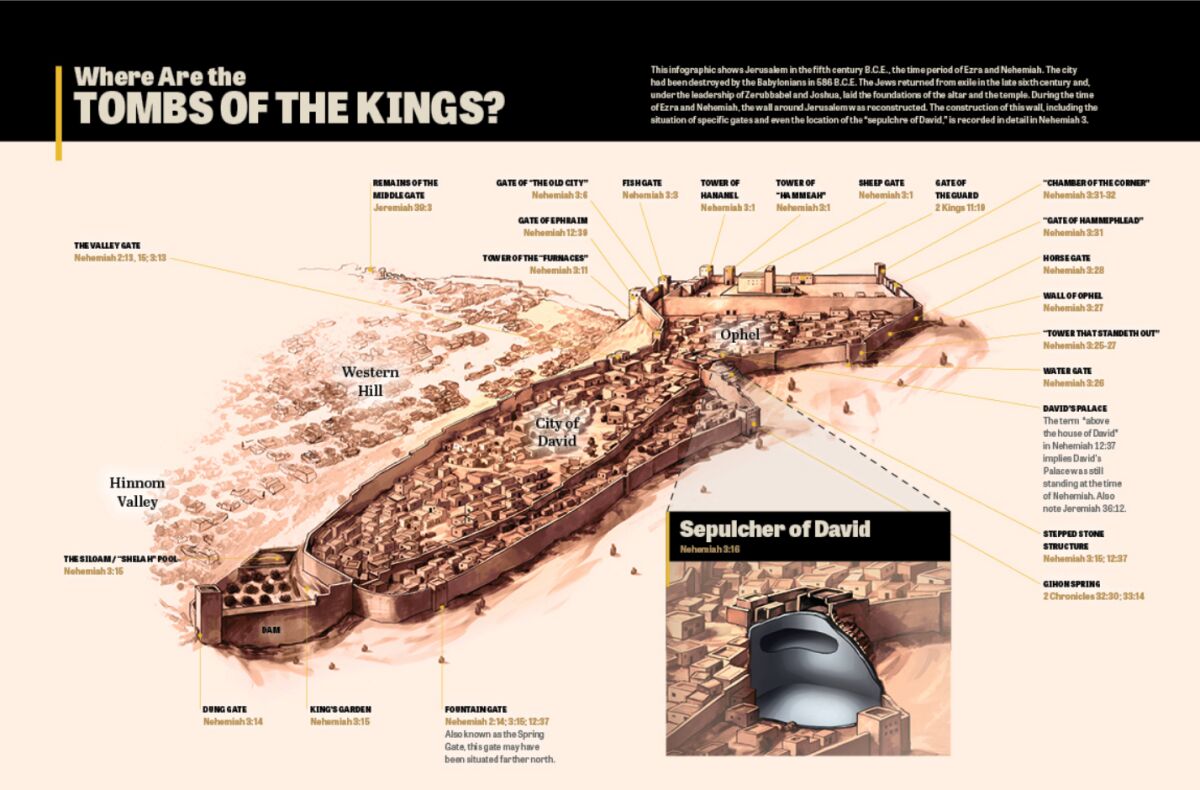

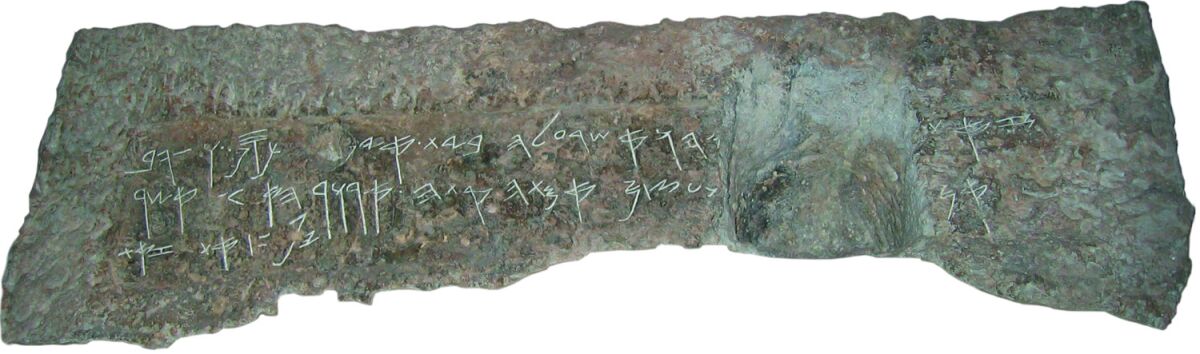

A good starting place is the book of Nehemiah. Set during the time when the Jews were rebuilding Jerusalem a century after the city had been sacked by Babylon, it gives some remarkable detail about the physical layout of the city at that time. It has become even more interesting in light of recent archaeological discoveries in Jerusalem.

Nehemiah 3 contains a list of the numerous gates that surrounded the city, starting at the Sheep Gate on the north (verse 1) and moving around in order, counterclockwise. Verse 15 describes the Fountain Gate, also known as the Spring Gate. In The Complete Guide to the Temple Mount Excavations, Dr. Eilat Mazar notes that this gate is located around the Gihon Spring. This verse says that after fixing this gate, a man named Shallun repaired “the wall of [or from] the pool of Shelah by the king’s garden, even unto the stairs that go down from the city of David.”

These “stairs” may refer to the Stepped Stone Structure—the remains of which exist in the City of David today—or a stairwell that merges into that structure. Nehemiah 12:37 describes a procession of musicians that went northward from the Gihon Spring, up “the stairs of the city of David,” and then beyond David’s palace—indicating that these stairs end near the palace.

Back in Nehemiah 3, after the Spring Gate and the stairs are listed, we read this: “After him repaired Nehemiah the son of Azbuk, ruler of half the district of Beth-zur, unto the place over against the sepulchres of David …” (verse 16). So Nehemiah the son of Azbuk (a different Nehemiah than the author of the book) carried on where Shallun left off—“unto the place over against the sepulchres of David.” The Jewish inhabitants of the city at this time apparently knew of these tombs and their location. And from this verse, it appears the tombs were located next to where the stairs ended.

Nehemiah’s counterclockwise description shows that the tombs of David—or at least their entrance—lie on the eastern side of the City of David. They are described as being between the Spring Gate and the Water Gate, which is the next gate listed (verse 26). That still covers a large area. If, however, the tombs are located between the “stairs that go down” (verse 15) and the “upper house” (verse 25)—which Solomon added to David’s palace immediately to the north—this would considerably narrow down the possible location of the access point.

If these tombs lie on the east side of David’s palace, “over against” the section of wall that Nehemiah repaired, that would place the entrance somewhere around where Dr. Eilat Mazar began digging at David’s palace in 2005.

Under David’s Palace?

Several scriptures refer to David and other kings of Judah as being buried in the City of David (e.g. 1 Kings 2:10; 11:43; 14:31; 15:8; 2 Kings 8:24).

David’s palace, as has been proved in Mazar’s excavations, was constructed outside the walls of the Jebusite fortress that David conquered in 2 Samuel 5:6-8. For years, it was commonly assumed David built his palace inside the city walls, because scholars always considered it part of the City of David. But there is no way a glorious palace would have fit within the cramped Jebusite city. David built it adjacent to the northern walls and then went down to the “hold”—that preexisting fortress—when the Philistines attacked (verse 17). Once it was attached to the city walls and more strongly fortified on the exterior, the palace would have been considered part of the City of David.

So when the Bible says the kings of Judah were buried in the City of David, that certainly could include somewhere under the palace (see this infographic).

It turns out that it was fairly standard practice for Judah’s leaders to build their tombs under their homes. Several scriptural references associate tombs of prophets and kings with their actual place of residence.

For example, when the Prophet Samuel died, the Israelites “buried him in his house at Ramah” (1 Samuel 25:1). The Jamieson, Fausset and Brown Commentary says this refers not to his dwelling-house, “but a building contiguous to it, built as a family cemetery; his own mausoleum. The Hebrews took as great care to provide graves anciently as people do in the East still, where every respectable family has its own house of the dead …” (emphasis added throughout).

Samuel’s burial is especially significant because he was David’s mentor. He anointed David as king. Throughout 1 Samuel, David continually turned to him for guidance and encouragement. And when Samuel died, David was on hand as the Israelites buried him in his house.

An article in Biblical Archaeology Review, “Lost Tombs of the Israelite Kings” (July-August 2007), described an interesting find regarding the palace of the Israelite King Omri (1 Kings 16), which was discovered in Samaria. Norma Franklin wrote that the builders carved a platform out of rock at one of the region’s higher points, similar to how David’s palace was constructed. Franklin believes she located two tombs under Omri’s palace, situated below the large courtyard of the palace. She wrote that Omri’s tomb was actually built first, before the palace was erected. She also described tunnels that were hewn into the side of the rock to make the tombs accessible to visitors.

The Israelites in Omri’s day may well have modeled their palaces after the design of David’s palace, especially considering Israel and Judah were once united under his reign.

In her article, Franklin quoted Isaiah 14:18: “All the kings of the nations, All of them, sleep in glory, Every one in his own house.” The king’s tomb, Franklin said, symbolized his house, which is why they were constructed underneath the palace. “David and his descendants, from Rehoboam to Ahaz, were all buried in their ‘houses,’ that is, in their palaces,” she wrote.

At times, God prevented certain evil kings from having this noble burial. In the case of Jehoram, 2 Chronicles 21:20 tells us that he was buried “in the city of David, but not in the sepulchres of the kings”—plural. Manasseh, one of Judah’s worst kings, was not buried in David’s sepulchre, but rather “in his own house” (2 Chronicles 33:20). 2 Kings 21:18 elaborates, saying Manasseh was buried “in the garden of his own house.” This was undoubtedly a palace that Manasseh or one of his ancestors constructed—one with a family tomb on the grounds.

Asa, on the other hand, was a righteous king. When he died, 1 Kings 15:24 tells us that he “was buried with his fathers in the city of David his father.” That is a clear reference to the tombs of the kings. After Josiah, another righteous king, died in battle at the Valley of Megiddo, his servants brought his body back to Jerusalem so he could be “buried in the sepulchres of his fathers” (2 Chronicles 35:24). So while there might be many smaller tombs scattered under the City of David, there is also one massive tomb for the righteous kings.

Besides these biblical references, archaeologists have also found evidence that monarchs of neighboring kingdoms, including the kings and queens of Assyria and five Babylonian kings, were also buried in their own palaces. In his article “Death Formulae and the Burial Place of the Kings of the House of David,” Tel Aviv University historian and archaeologist Nadav Naaman wrote, “[T]he practice of burying kings in their ‘houses,’ namely their palaces, conceived as places of dwelling and rest in life and afterlife, was widespread all over the ancient Near East. This supports the assumption that the kings of the house of David were also buried in the royal palace” (Biblica 2004, Vol. 85, Fasc. 2).

If David expanded northward from the Jebusite city to build his palace, it would have made sense to also build new tombs underneath that palace, as Omri would later do. And if the design of David’s tomb was anything like Omri’s, the entrance could be close to the courtyard of David’s palace, much of which has already been exposed by Dr. Mazar’s excavations.

The ‘High Place’

Isaiah 22 relates a story about a treasurer named Shebna who served in Hezekiah’s court. Notice how God used His prophet to correct this man for his pride: “What hast thou here, and whom hast thou here, That thou hast hewed thee out here a sepulchre, Thou that hewest thee out a sepulchre on high, And gravest a habitation for thyself in the rock?” (verse 16).

Apparently, God sent His prophet to the very place Shebna was busily and presumptuously preparing his own grand sepulcher. Why would this vain man have been carving out a tomb into a rock “on high”? Because that’s where the kings in Judah were buried. Shebna coveted a “nest on high,” just like the man spoken of in Habakkuk 2:9.

Ezekiel 43:7 references the fact that the kings in Judah were buried “on high”: “And He said unto me: ‘Son of man, this is the place of My throne, and the place of the soles of My feet, where I will dwell in the midst of the children of Israel for ever; and the house of Israel shall no more defile My holy name, neither they, nor their kings, by their harlotry, and by the carcasses of their kings in their high places.” In this prophetic vision, God is speaking of a time when He will rule in Israel and remove all barriers that once divided Him from His people. He describes the place of His throne as being in close proximity to the place where the kings’ bodies currently lay. This suggests that the tombs are somewhere near the throne room. The International Critical Commentary says, “It is implied that the kings were buried … near to their palace.”

Ezekiel says the kings were buried “in their high places,” where Shebna arrogantly tried to carve out his tomb. The question is, where would the “high place” be at the time David’s sepulchers were carved?

As Dr. Mazar wrote in her groundbreaking 1997 article, “We know quite a bit about this city [the City of David]—from excavations, topography and the biblical text” (“Excavate King David’s Palace,” Biblical Archaeology Review, January-February 1997). Indeed, the biblical text reveals that the only royal building constructed at the time the tombs were made was King David’s palace. As she went on to explain, when the Philistines approached to attack the city, David went down to the fortress. In other words, David’s palace was situated on the highest point of the city. Before Solomon enlarged the city, the palace was the “high place.”

So when God says the bones of Judah’s kings were buried in their “high places,” it’s logical to assume they were buried at the peak of the city during David’s reign—just underneath the palace.

Raiding the Tombs

Here is how Josephus, the famous first-century Jewish historian, described King David’s burial: “He was buried by his son Solomon, in Jerusalem, with great magnificence, and with all the other funeral pomp which kings use to be buried with; moreover, he had great and immense wealth buried with him ….”

The wealth within this tomb was no secret, nor was its location. In the second century b.c.e., about 830 years after David was buried, the first known raid of the tomb occurred. As Josephus described it, Hasmonean leader Johanan Hyrcanus was under siege in Jerusalem by Antiochus vii of the Seleucid Empire. In desperation, he forged a truce agreement that involved a payment of 3,000 talents of silver. Having no other means of acquiring the money, Hyrcanus opened one room of David’s sepulcher, withdrew 3,000 talents, and paid Antiochus (Antiquities of the Jews, Book 13, Chapter 8, Number 4).

Hyrcanus only raided one room of the tombs. A hundred years later, King Herod determined to pick up where Hyrcanus left off. Known for his vast building projects throughout Jerusalem, Herod had heard that Hyrcanus had left behind a tremendous amount of wealth. Josephus related that Herod planned a raid for some time, then “he opened that sepulcher by night, and went into it, and endeavored that it should not be at all known in the city, but took only his most faithful friends with him. As for any money, he found none, as Hyrcanus had done, but that furniture of gold, and those precious goods that were laid up there; all which he took away” (ibid, Book 16, Chapter 7, Number 1).

Why did Herod do this secretly, at night? He certainly had enough power to do as he pleased in Jerusalem. Perhaps since he was half-Jewish, his conscience prevented him from openly desecrating the tombs of the kings. Or maybe he knew that raiding the tombs in broad daylight would trigger a war with the Jews.

The success of this plunder made Herod greedier. “[H]e had a great desire to make a more diligent search, and to go farther in, even as far as the very bodies of David and Solomon,” Josephus wrote. However, as two of Herod’s guards approached the bones of David and Solomon, according to Josephus, they were killed “by a flame that burst out” on them! By all appearances, God struck them dead!

This supernatural jolt prompted Herod to abandon the project and to erect a monument. “So he was terribly frightened, and went out, and built a propitiatory monument of that fright he had been in; and this of white stone, at the mouth of the sepulcher, and that at great expense also” (ibid).

Of the three tombs discovered in the Kidron Valley in 1989, two had stone doors with hinges sealing the entrance; one even had an intact locking device. “Hinged stone doors are rare in the tombs of the Second Temple period; they are mostly found in the largest and most sumptuously appointed tombs, such as the tombs of the kings. This method of sealing burial chambers became more common in the late Roman period …” (Hillel Geva, Ancient Jerusalem Revealed). Perhaps Herod built a huge impenetrable door blocking access to the tombs after the frightening incident involving his two guards; maybe he erected a huge monument in front of a hinged door that was already there. In any event, the tomb was well fortified after those two robbers were struck dead.

It’s a fascinating bit of history.

Location Still Known

A generation after Herod’s death, we find a reference to the tombs of the kings in the New Testament book of Acts. Speaking in 31 c.e., the Apostle Peter said, “Men and brethren, let me freely speak unto you of the patriarch David, that he is both dead and buried, and his sepulchre is with us unto this day” (Acts 2:29; King James Version). Peter referred to David’s tomb as if its location were common knowledge in Jerusalem at that time. In his sermon, he was discussing the resurrection of Jesus Christ. David wasn’t yet resurrected, Peter told the people. He’s over there still lying in his tomb. (Also note Jeremiah 30:9.)

Josephus was born a few years after Peter made that remark. Putting Peter’s comment together with the history Josephus wrote about, clearly, the whereabouts of David’s tomb was known during the first century c.e.

Even as late as the early third century, we find a historical reference to David’s sepulcher. In the Tosefta (220–230 c.e.), there is a dialogue about what to do about tombs that were near cities. It explains that, except for kings and prophets, the Israelites always buried their dead outside the city walls. “Now were not the graves of the house of David and the grave of Hulda the prophetess in Jerusalem,” it says, “and no one ever laid a hand on them” to move them. Then R. Aqiba responds, “What proof is there from the fact? In point of fact they had underground channels, and it would remove uncleanness to the Qidron Brook” (Tosefta, Fourth Division, Neziqin, Baba Batra 1:11; Jacob Neusner translation).

This description of the tombs having underground channels that empty into the Kidron Valley indicates that David’s tomb lay along the eastern ridge of the City of David, as Nehemiah suggested. More importantly, the Tosefta relates that no one laid a hand on the contents of David’s tomb. This is an important reference because it is long after Titus sacked Jerusalem in 70 c.e., indicating that the tombs escaped desecration.

So as late as the third century—nearly 1,200 years after David’s burial—we find a clear reference to the location of the tombs of the kings. And besides the wealth confiscated by Hyrcanus and Herod, its contents were still unmolested.

Since that time, David’s sepulcher has remained hidden from world view.

Discovery Awaits

Excavation in recent years is bringing the history of Israel’s kings—even as early as King David—back to life from the ancient soil of Jerusalem. A substantial portion of David’s palace has been uncovered in the City of David. More excavation has yet to take place there.

Will the tombs of the kings be located under that palace? It would be an electrifying discovery that would give even greater credence to the reliability of the historical account contained within the pages of the Bible.