One could be forgiven for concluding that the marriage of Abram and Sarai (later renamed Abraham and Sarah) was no Romeo and Juliet affair. Certain details found in the biblical account likely will come across as surprising, if not shocking—a “brother-sister” relationship, the apparent ease with which Abram relinquished Sarai to the pharaoh, the Hagar episode.

Actually, there is much more to each of these points than meets the eye. The past decades and centuries of archaeological practice have produced numerous discoveries, including texts from the second millennium b.c.e., which serve to illustrate such practices and deeds ascribed to Abram and Sarai as common fare—par for the course in the ancient Near East.

In this article, we’ll review a handful of examples.

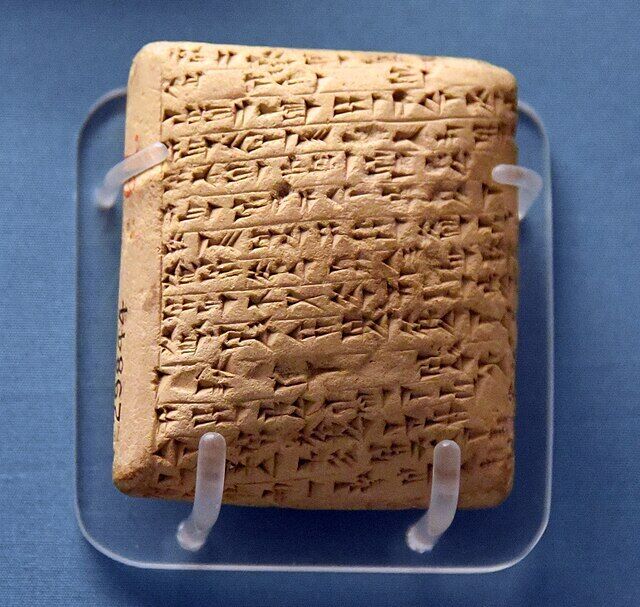

EA 254: Wife or Life

Soon after the description of Abram and Sarai’s arrival in Canaan, we read the following from Genesis 12: “And there was a famine in the land; and Abram went down into Egypt to sojourn there; for the famine was sore in the land. And it came to pass, when he was come near to enter into Egypt, that he said unto Sarai his wife: ‘Behold now, I know that thou art a fair woman to look upon. And it will come to pass, when the Egyptians shall see thee, that they will say: This is his wife; and they will kill me, but thee they will keep alive. Say, I pray thee, thou art my sister; that it may be well with me for thy sake, and that my soul may live because of thee.’ And it came to pass, that, when Abram was come into Egypt, the Egyptians beheld the woman that she was very fair. And the princes of Pharaoh saw her, and praised her to Pharaoh; and the woman was taken into Pharaoh’s house” (verses 10-15).

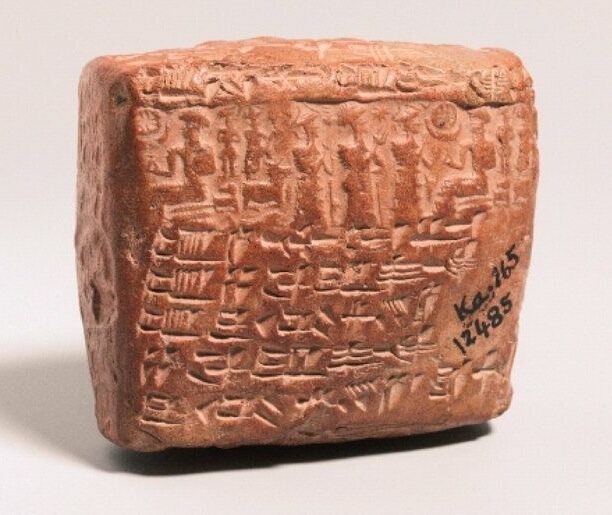

In light of this passage is an interesting tablet from slightly later—the 14th century b.c.e.—that aptly demonstrates the same principle. This tablet, or “letter,” comes from the Amarna archive—specifically EA 254—a letter from the Canaanite ruler of Shechem, Labayu, to the pharaoh. The beginning and ending of the tablet demonstrates some of the typical ludicrous platitudes offered to appease the pharaoh:

[Intro:] To the king [pharaoh], my lord and my Sun: Thus Labayu, your servant and the dirt on which you tread. I fall at the feet of the king, my lord and my Sun, seven times and seven times. I have obeyed the orders that the king wrote to me. …

[Main body and substance of the letter]

[Conc:] Moreover, how, if the king wrote for my wife, how could I hold her back? How, if the king wrote to me, “Put a bronze dagger into your heart and die,” how could I not execute the order of the king?

Thus concludes—rather dramatically—Labayu’s deferential letter. If the pharaoh wanted his wife, she was his—any questions or protest would be futile. If the pharaoh wanted him to die, he was dead—no questions or protest. (Ironically, Labayu did end up dead shortly after—murdered while being transported to Egypt for questioning.)

In Abram’s case, the best he could have hoped for out of such a situation of inflamed pharaonic passion would be to escape with his life. To this end, it is interesting that Labayu follows his hypothetical of pharaoh’s desire for his wife with pharaoh’s desire for his life—while it is easy to read these as two separate statements of Labayu’s slavish fealty, in light of the Abram account, one can’t help but also wonder if they are connected—pharaoh’s desire for his wife also logically resulting in his death. Adulterous unions in ancient Egypt, after all, resulted in the death penalty (depending on the circumstances).

Regardless, EA 254 gives us a glimpse into the Egyptian world into which Abram was entering—and the severe risks taken to stay alive during a time of famine. Hunger is a cruel taskmaster.

But naturally, from the comfort of our 21st-century armchairs and gluttonous diets, we can’t help but question the morality of it all. How could Abram simply relinquish his wife in such a manner? To this, Rochel Holzkenner wrote in her interesting article, “How Could Abraham Let Sarah Be Abducted?”:

In the book of Genesis our biblical heroines are powerful in a modest and discreet way; their husbands in turn are respectful and protective. Women are cherished and honored. Such has also been the Jewish tradition ever since the days of our patriarchs and matriarchs. Which makes one story in Genesis [that of Abram and Sarai in Egypt] really stand out. …

What is the solution? She points out the traditional Jewish explanation that “Abraham was not confident that he was worthy of being saved from death, but he was fully confident” that God “would never allow his holy wife to be violated. … And this is in fact what happened. Sarah was taken, but a few hours later she walked away untouched.”

It’s a nice explanation. Other readers, however, might have been more hung up on another point entirely—one which we read right over in this account: a brother-sister relationship?

My Sister, My Bride

Sarai is indeed referred to a number of times as Abram’s “sister”—presented as such to both the pharaoh and king of Gerar (Genesis 12:19; 20:2). Yet the astute observer will know that there is more nuance to this. In the clarification of Abram to the king of Gerar: “[M]oreover she is indeed my sister, the daughter of my father, but not the daughter of my mother; and so she became my wife. And it came to pass, when God caused me to wander from my father’s house, that I said unto her: This is the kindness which thou shalt show unto me; at every place whither we shall come, say of me: He is my brother” (Genesis 20:12-13).

Hence a typical understanding is that Abram and Sarai were half-siblings—justifiably calling each other “brother” and “sister,” but with an additional step of separation—Abram and Sarai sharing the same father (Terah), but different mothers.

Yet there’s another angle here—the fact that such half-sibling unions were explicitly banned later in the Torah. “And if a man shall take his sister, his father’s daughter, or his mother’s daughter [thus either full or half-siblings] … it is a shameful thing; and they shall be cut off in the sight of the children of their people” (Leviticus 20:17). “Cursed be he that lieth with his sister, the daughter of his father, or the daughter of his mother” (Deuteronomy 27:22).

Some reason that these laws did not apply at the time of Abram—and that perhaps in the same way Cain, Abel and Seth are commonly inferred to have married sisters without fear of deleterious genetic effects so early on Genesis history, perhaps the same may have been true at least for half-siblings at the time of Abram.

Other theories propose identifying Sarai with the slightly more distantly-related Iscah mentioned in Genesis 11:29 (Abram’s niece, and thus a somewhat more distant “daughter” [granddaughter] of Terah—this is a common traditional Jewish explanation). Still, this seems a stretch, on the basis of both names (Sarai and Iscah) being used in this very same verse, for what otherwise appears to be different individuals. Still others reason Abram’s qualification to the king of Gerar to have been a deception.

Yet there’s even more to all this than meets the eye, in our first introduction to Sarai in Genesis 11.

In this passage, the names of Terah’s sons are given, later followed by his son’s wives—Milcah, Nahor’s wife, and Sarai, Abram’s wife. In this passage, the latter is identified as “Sarai his [Terah’s] daughter-in-law, his son Abram’s wife” (verse 31)—identifying her strictly as Terah’s daughter through marriage, rather than descent. The same Hebrew word is used to describe the relationship between Judah and Tamar, Naomi and Ruth, Eli and his son’s wife, etc—daughters-in-law, relatives through marriage. If Sarai was Terah’s own daughter (based on a face-value reading of Genesis 20:12), it seems odd for her to be introduced alongside the rest of Terah’s offspring simply as his daughter-in-law. What is going on here?

Ancient legal texts offer answers to these questions. These refer to the common use of the legally adoptive titles “sister,” “daughter,” etc, used among families of Mesopotamia, which conferred certain rights, privileges and/or advantages to various parties, depending on the circumstances and contracts. Prof. Marten Stol writes at some length about these subjects in his excellent 700-page book Women in the Ancient Near East, cross-referencing troves of ancient cuneiform texts. Note the following examples (emphasis added throughout):

[I]n a text from Nuzi, Wullu adopted a girl for marriage to his son “or to anybody else in the area.” … An Old Babylonian contract … concerns an adoption with a view to marriage of a girl called Sabitum. She is described in the first line of the contract as “the daughter of Ibbatum” …. Ibbatum states that he has adopted her as his daughter. … Another example of this is the father Sin-abušu acting as a witness to the adoption of his daughter Iltani as a sister. … Elsewhere and still with the same structure, we find the record of the adoption of a girl who was evidently not so poor (she was a priestess) and there again there are the strict clauses on divorce and the “second father.” …

In the Old Assyrian trade colony of Kaniš we see something similar among the native Anatolians. A married couple adopted a girl and their son married her. … Here there was no profit motive behind the adoption.

In the Nuzi texts this sort of adoption with a view to marriage occurs frequently, including the expression “adoption as a daughter” …. A girl could simply be adopted as a daughter for a payment lower than a brideprice. … Every case was different and the first example is of a brother who had brought up his sister and was now giving her to P. “as a daughter” for 40 shekels of silver, the usual full bride-price. …

Once a woman married a man and brought her daughter with her, and the man adopted her as his “daughter.” The woman was bringing with her to the marriage a daughter she herself had adopted and reared.

Based on this level of precedent, we may surmise that Abram and Sarai were not necessarily related by blood at all. Instead, Sarai may have been drafted into Terah’s family as an adoptive “daughter” (and thus “sister” to Abram) at a young age—either legally ascribed as a “daughter” to Terah alone, or brought along by another wife (not Abram’s mother, per Genesis 20:12)—who herself may not necessarily have been her “real” mother. This could also add meaning to the final “throwaway” line in Genesis 20:12: “and so she became my wife.” Far from this implying that Sarai became Abram’s wife because she was his blood relation, it would instead make sense if she was intentionally adopted into the family at a young age by Terah for this purpose of marriage to Abram.

Stol continues:

In general, when we see the words “sister” and “parents,” we should take into account the fact that a poor girl or slave-girl would have been adopted by her “parents” with the intention of later marrying her off …. What lies behind this must be the rule that marriage could only legally be contracted by free persons. The adopted woman was free …. The adoption process was necessary to make her a completely free woman.

We see clearly, then, the common exchangeable nature of the titles “daughter” and “sister” relationships in the Mesopotamian world—titles very far removed from common assumptions of blood-relation. All of this, in turn, would potentially fit with other hints found in the biblical account—that Sarai was distinctly someone else, from somewhere else (another subject for another day).

Interestingly, the same brother-sister refrain is found being used by Isaac and Rebekah (Genesis 26:7-9), who certainly were not blood-siblings—but whom also may well have entered into just such an adoptive marital contract.

But before Isaac, there was Ishmael—and another interesting episode.

Surrogacy

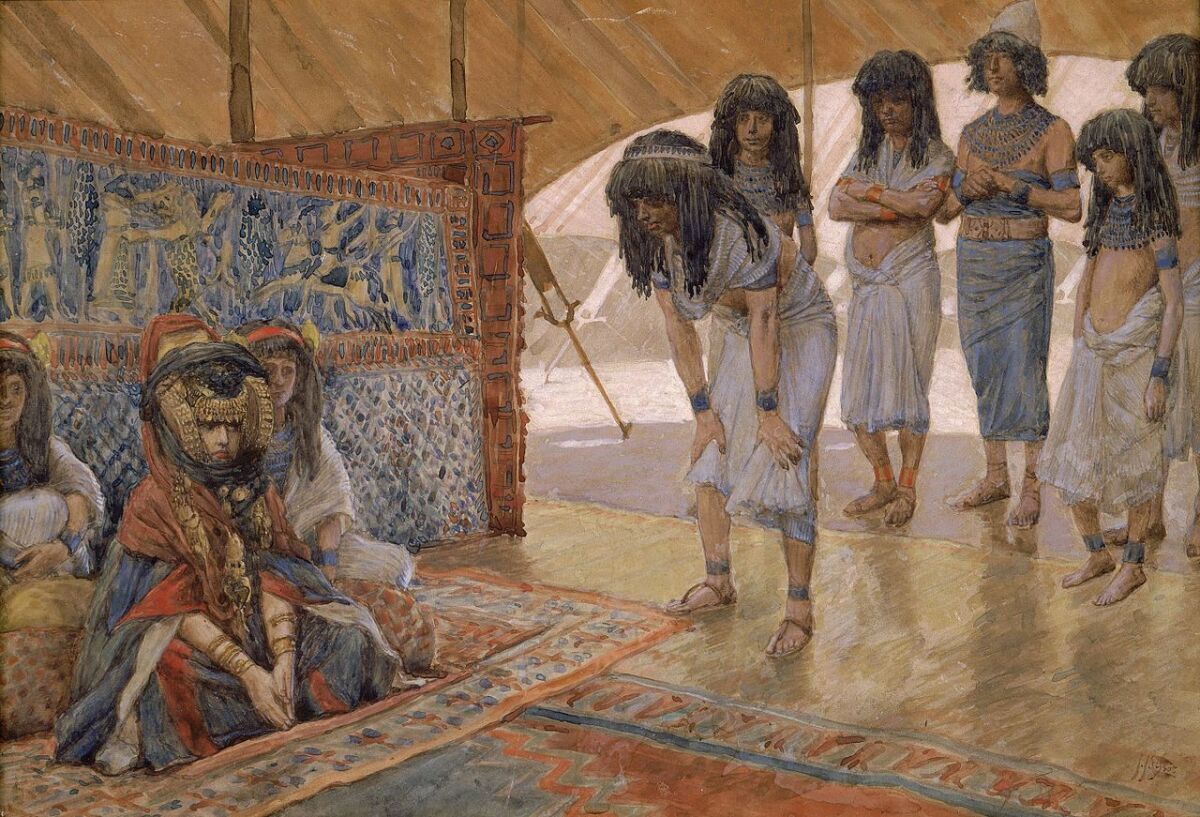

It’s another hiccup along the way, to say the least—one that has famously resulted in lasting conflict, to this day. The biblical story of Hagar is well known: Abram’s wife, Sarai, was unable to bare a child. Knowing God’s promise of a son, yet doubting the means because of her old age, she offered her handmaid Hagar to Abraham to serve as a surrogate. “And Sarai said unto Abram, Behold now, the Lord hath restrained me from bearing: I pray thee, go in unto my maid; it may be that I may obtain children by her. And Abram hearkened to the voice of Sarai” (Genesis 16:2; King James Version).

This act was clearly contrary to God’s designs. But, as numerous texts reveal, it is a deed layered thoroughly with legal precedent.

First, note the interesting (and surprising) fact that it was the woman—Sarai—who proposed Abram take on another—specifically, her “handmaid.” Yet this is a key feature of ancient practice in the case of childlessness—first, that the wife would provide a substitute; and second, that it would be in the form of some kind of “slave-girl.” Stol notes a “marriage contract in which two women are involved and the possibility of childlessness is discussed,” quoting the text directly as follows (here cutting partway into the contract):

“If within two years she [the wife] has acquired no offspring for him, she herself shall buy a slave-girl and as soon as this girl later gets a child for him, she can sell her wherever she wishes.” …

[I]n the case of childlessness a slave girl [is] bought by the first wife if she herself was infertile. … [I]n a Neo-Assyrian contract a very independent lady at the court promised that she herself would provide a slave-girl in the case of childlessness. …

One text records a decision for a childless woman to take a “woman from the land of Lullubu as a wife” for her husband and any children would have to obey her. This woman must have been a slave-girl from the hill country. …

When a high-ranking lady at the court gave her daughter S. in marriage, it is stated: “If S. does not become pregnant and does not bear a child, she shall take a slave-girl as a replacement for herself. In this way she shall bring forth sons. The sons will be her sons. If she loves her, she shall protect her. If she hates her, she shall sell her.”

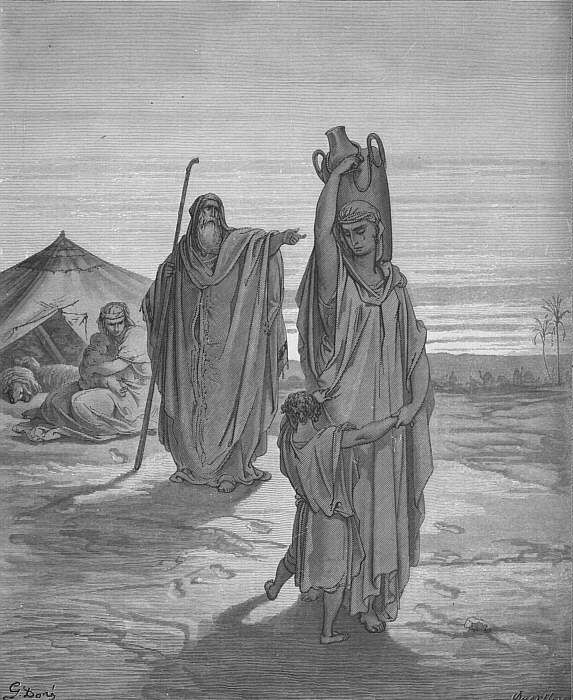

Suffice it to say, in light of the latter text—just like with the triad of Abram, Sarai and Hagar—such marital situations involving surrogacy fomented intensely strained situations. As ill-advised as such relations were for marital harmony, Abram and Sarai’s actions nevertheless represented standard practice. And just as it was Sarai who took the typical prerogative of bringing in the surrogate, it was also on her initiative that Hagar was sent away (e.g. Genesis 16:6; 21:10)—likewise fitting with the aforementioned standard practice.

Of additional, final note here is the unusual attention given in the biblical account to the amount of time that had passed before Hagar was initially offered by Sarai: “And Sarai Abram’s wife took Hagar the Egyptian, her handmaid, after Abram had dwelt ten years in the land of Canaan, and gave her to Abram her husband to be his wife” (Genesis 16:3). Why such careful detail, inserted within a train of thought that might otherwise be read more smoothly without? This too fits with ancient precedent—varying regions specifying certain “waiting times” before taking on an extra woman to produce an heir.

Stol writes of the practice in the region of Alalakh (on Turkey’s southern border with Syria):

Two wives would have been normal in the west …. [T]exts from Alalaḫ grant a period of seven years for the woman to produce a child. If in that time she has no child, the man may marry a second wife. Setting a time limit for producing children, after which a man may marry a second wife, is confined to the north and the west of the region. In Assyria two years was allowed, but in Alalaḫ it was seven or 10 years.

In the Bible Sarai brought in Hagar as a second wife for Abram after staying 10 years in Canaan (Genesis 16:3).

Undoubtedly, then, the inserted reference to a 10-year period in Genesis 16:3 is to carefully couch this deed as specifically following certain legality.

Many of these events, deeds and practices are highlighted in the biblical account not as exemplary acts to be emulated (indeed, they are quite clearly described in the narrative as contrary to God’s plans and designs, for which Abram and Sarai paid the price). Nonetheless, one gains a new appreciation for Abram and Sarai’s marriage based upon what would have been common practices under specific circumstances—deeds that would only have been expected of individuals in their circumstances in the times and places in question—laws Abram and his wife would have been well familiar with (especially given other accounts of Abram as a leading educator within Mesopotamia).

It is common to fall into the trap of “presentism” when observing the past—viewing it through the lens of modern-day values and ideas. But we can just as easily flip the script and imagine Abram and Sarai reading about certain marital relations and practices in our day and age.

I venture to say, they just might be horrified.