Dominus illuminatio mea—the Lord is my light. This phrase, taken from the first verse of Psalm 27, serves as the motto for the University of Oxford. As the English-speaking world’s oldest educational institution, its reputation as a center for learning and scholarship dates back to at least 1096. For centuries since then, the University of Oxford’s educational programs have changed the course of Western civilization. Its alumni include kings Edward vii and viii, 25 British prime ministers, at least 36 foreign heads of state or government and 56 Nobel laureates. The last seven prime ministers of the United Kingdom were all educated in Oxford. Its literary tradition includes such students and professors as Lewis Carroll, Oscar Wilde, C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Percy Bysshe Shelley and many others.

But Oxford is not just a prestigious place for an education in secular studies.

Although it does not intentionally promote biblical history, at Oxford’s heart is an institution that has artifacts that illuminate the biblical story: the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology.

Founded in 1683, it is Britain’s first public museum and one of the oldest museums in the world. Its original collection grew from the “cabinet of curiosities” of its inaugural donor and namesake Elias Ashmole. This original collection was mostly made up of specimens from the natural world. The collection later branched out to include archaeological finds. Its modern building was constructed between 1841 and 1845 to house the university’s collection of classical statuary and fine arts. This institution merged with the Ashmolean’s collection to form the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology in 1908.

Today, the Ashmolean Museum has become Oxford’s premier archaeological institution. This includes displaying several important artifacts relating to biblical archaeology.

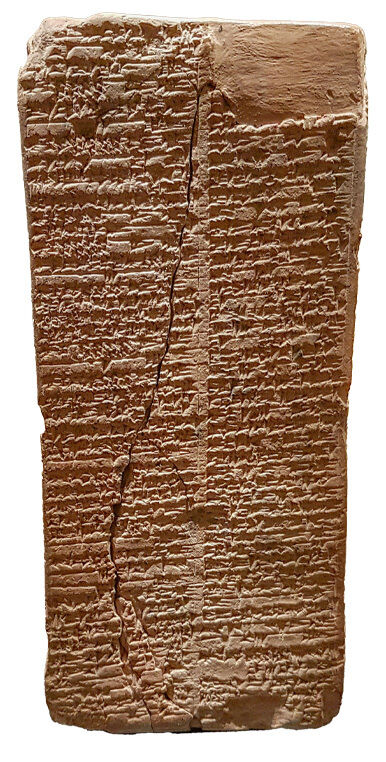

The Sumerian King List

“When kingship had come down from heaven, kingship was at Eridu. Alulim was king; he reigned 28,800 years; Alagar reigned 36,000 years; two kings reigned 64,800 years. Eridu was abandoned; its kingship was taken to Bad-tibira.” So starts the Weld-Blundell Prism,

better known as the Sumerian King List. This ancient document records how the Sumerians, the earliest major civilization of the Fertile Crescent, believed their earliest history transpired.

Antiquarian Herbert Weld-Blundell gifted it to the museum in 1923. It is unclear how Weld-Blundell first acquired the prism; he had sponsored an excavation at the Mesopotamian city-state of Larsa but may have acquired it from an antiquities dealer. The museum regards Larsa as its most likely provenance and dates it to circa 1800 b.c.e. Larsa was one of the last powerful Sumerian city-states before the Akkadian-speaking Babylonians conquered Sumer.

The king list starts tens of thousands of years into the legendary past. It lists dynasties ruling from particular city-states, jumping from city to city as their kingships gain prominence. Eventually, it lists kings who are independently verifiable in the historical record, including famous names such as Sargon of Akkad.

Several important details of the king list relate to the Bible:

- The earliest kings have astronomically long reigns. The king list states King Enmen-lu-ana of Bad-tibira reigned for 43,200 years. This parallels the long lifespans the Bible gives of the pre-Flood world in Genesis 5. (The lifespans in the Bible aren’t nearly as long, but there is a way to synchronize the lifespans of the Bible and the king list).

- After the first eight kings, the king list records: “The Flood swept over.” Genesis lists 10 generations from Adam to Noah through the line of Seth before the biblical deluge (Genesis 5) and eight generations through the line of Cain (Genesis 4), paralleling the king list.

- After the Flood, lifespans shrank, similar to the Bible’s account.

- The king list also mentions “Enmerkar, son of Meskiagkasher, the king of Uruk, the one who founded Uruk.” Enmerkar may have corroboration with the biblical warrior Nimrod (Genesis 10:8-10), who the Bible says founded Uruk/Erech.

Jericho Skull

Uncovered in 1953 by Dame Kathleen Kenyon, this is one of several ritually decorated skulls found in Jericho. These skulls were part of an ancient burial practice in which the skull of a deceased individual was covered in plaster and shells were used to cover the eye sockets.

Jericho is famous as the city Joshua conquered (Joshua 6), but this skull dates to well before that time. Attributed by Kenyon to the Neolithic period, this represents one of the oldest known “portraits” ever discovered.

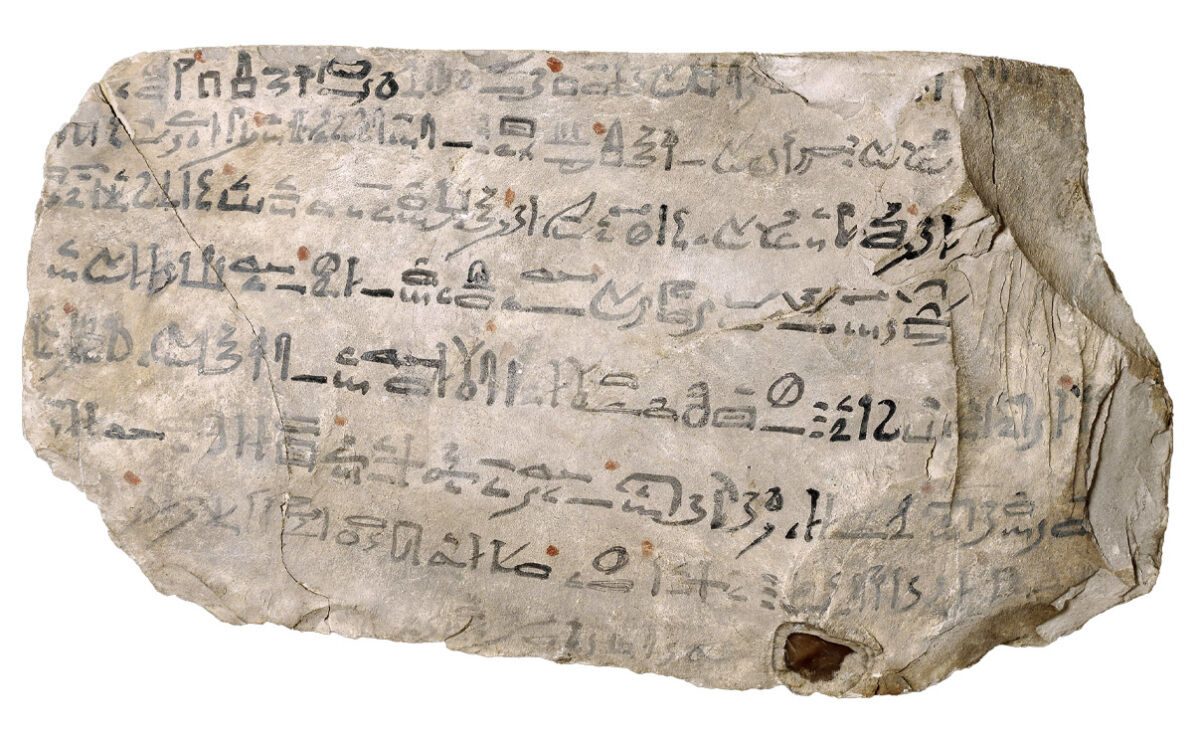

The Sinuhe Ostracon

This is the largest known limestone ostracon (a sherd of pottery or stone with writing) discovered from Egypt. It narrates a story known as “The Tale of Sinuhe,” where a courtier named Sinuhe flees to the Levant after the death of Pharaoh Amenemhat i (c. 1938–1908 b.c.e.). On his journey, Sinuhe almost dies of thirst but is rescued by a local chieftain and revived. While abroad, he marries the daughter of another benefactor.

“The Tale of Sinuhe” has remarkable similarities with the story of Moses, who fled the wrath of a pharaoh after killing a man, stayed in exile with a Levantine chieftain, and married his daughter (Exodus 2:11-22).

The Sinuhe Ostracon was recorded sometime around 1292–1190 b.c.e., but the story itself dates to an earlier period and remained a literary classic in ancient Egypt for centuries.

Jasper Seal of ‘Hannah’

The Ashmolean dates this stone seal to circa 750–700 b.c.e. It originally came from

Lachish, one of Judah’s major cities at this point in its history. Its Paleo-Hebrew text reads: “Belonging to Hannah.” Seals for prominent individuals are relatively common finds in Iron Age Israel, but seals belonging to women are not. This would not have been the biblical matriarch Hannah (1 Samuel 1), who lived hundreds of years earlier. But it is still an extrabiblical example of her name.

Fertility Figurines

The fertility figurines housed in the Ashmolean Museum were discovered by Kenyon on Jerusalem’s Ophel, a ridge first developed under King Solomon. The museum dates these fertility figurines to circa 750–650 b.c.e. These were most likely depictions of the Canaanite fertility goddess Ashtaroth, consort of the storm god Baal and counterpart to Mesopotamia’s Ishtar (e.g. Judges 2:13; 1 Samuel 12:10). The Bible states such pagan worship is one of the main sins that sent Judah into captivity.

LMLK Handles

In the late eighth century b.c.e., Judah faced an invasion from the mighty Assyrian Empire under King Sennacherib, as recorded in 2 Kings 18-19, Isaiah 36-38 and 2 Chronicles 32. Judah’s King Hezekiah prepared Jerusalem for the impending siege (e.g. 2 Chronicles 32:2-5).

Jar handles with the paleo-Hebrew inscription lmlk (“belonging to the king”) dating to this time period have been discovered throughout Israel. It’s believed they were part of Hezekiah’s logistical reorganization in anticipation of the Assyrian invasion. The Ashmolean has several of these handles on display.

Of note is the winged sun symbol carved into some of the handles. This fits with the general iconography of the period. A Jerusalem seal impression belonging to Hezekiah shows a very similar symbol. Taken together, this may suggest a winged sun was a personal symbol of Hezekiah.

The Shrine of Taharqa

The Shrine of Taharqa is the largest intact ancient Egyptian building in the United Kingdom. It was originally from the ruins of Kawa, between the Nile’s third and fourth cataracts in what is today Sudan.

Taharqa, who reigned in the early seventh century b.c.e., was originally from Kush (an African kingdom based in northern Sudan). His family had conquered Egypt and established an empire stretching to the Mediterranean coast. He was a noted builder who commissioned new structures in Memphis and Thebes, Egypt’s historic capitals. Taharqa was a contemporary of Hezekiah and is one of the few pharaohs named in the biblical account (e.g. 2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9—both mention “Tirhakah king of Ethiopia” fighting against the Assyrians).

The shrine is dedicated to the Egyptian pantheon’s chief god, Amun-Ra. While traveling north to Egypt, young Taharqa spotted a decaying temple at Kawa. Upon becoming pharaoh, he decided to rebuild it. Importing architects from Egypt, Taharqa’s work took four years to complete.

The Ashmolean’s shrine was discovered in 1930 during an Oxford-sponsored excavation. The Sudanese government gifted the shrine to the University of Oxford. Archaeologists disassembled the building, shipped the 236 sandstone blocks to England, and reassembled it in the Ashmolean.

Stone Shekels

The modern New Israeli Shekel currency takes its name from a biblical unit of measurement. The shekel originally was a weight used for trading silver and gold (Genesis 23:16; 24:22). The most common method of engaging in trade was through hacksilver—piles of silver pieces used as a makeshift “currency.” Stones like these would have been weighed to confirm the measurements of the precious metals.

The Bible does not specify exactly how much one shekel weighed. But the Ashmolean’s stones help answer the question. The red stone, with a measured weight of 45.3 grams, has an inscription stating it weighs 4 shekels. The largest stone is inscribed as weighing 16 shekels.

The stones were found in Jerusalem. The Ashmolean dates them to between 650–587 b.c.e., just before the Babylonian destruction. By the time Persia conquered Babylon and Cyrus the Great allowed the Jews to return to Judah, the Persian government had introduced coinage through the empire. The old system of weighing hacksilver was phased out.

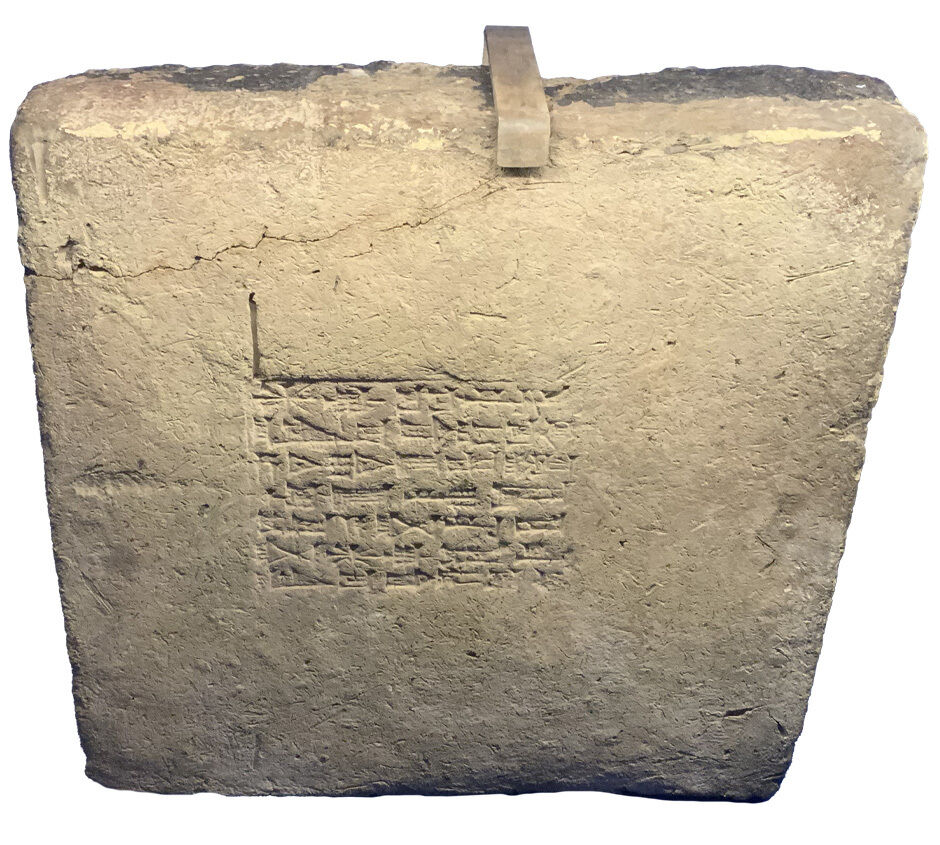

Nebuchadnezzar’s Brick

Nebuchadnezzar ii of Babylon (r. 605–561 b.c.e.), mentioned prominently in the books of Jeremiah and Daniel, was one of the ancient Middle East’s most powerful rulers. His empire extended from the eastern Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf. Nebuchadnezzar was a noted builder, commissioning monuments like Babylon’s famed Ishtar Gate. Nebuchadnezzar’s vision for Babylon can be summed up in what he said in Daniel 4: “Is not this great Babylon, which I have built for a royal dwelling-place, by the might of my power and for the glory of my majesty?” (verse 27).

Nebuchadnezzar had individual bricks of his buildings stamped with his insignia. This was one such brick. Its text, written in an archaic form of cuneiform in homage to Babylon’s history, reads: “Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, who provides for Esagila and Ezida [two religious sites], the eldest son of Nabopolassar, king of Babylon am I.”

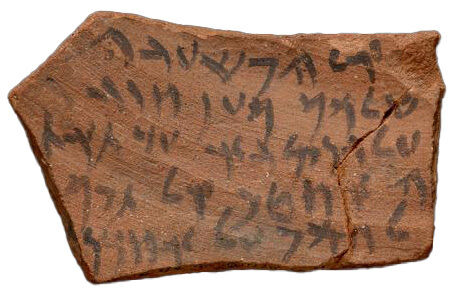

The Passover Potsherd

During the Persian Empire (559–330 b.c.e.), a unique Jewish community flourished on the island of Elephantine in the Nile River, near Egypt’s border with Nubia. Possibly the descendants of Jewish mercenaries recruited by a pharaoh to fight the Kushites, they developed their own customs and even set up their own temple rivaling the one Zerubbabel built in Jerusalem (Zechariah 4:9). This ostracon was a letter between two households and is dated to 475 b.c.e., the time of Persia’s King Xerxes (or Ahasuerus; Esther 1:1). It reads:

To Hosea, greetings! Take care of the children until Autab gets there. Don’t trust anyone else with them! If the flour for your bread has been ground, make a small portion of dough to last until their mother gets there. Let me know when you will be celebrating Passover. Tell me how the baby is doing!

The Passover Potsherd is one of the oldest known extrabiblical references to Passover.

Dead Sea Scroll Jar

Three Bedouin shepherds in 1947 were looking for a missing goat near the archaeological site of Qumran at the northern end of the Dead Sea. One of the shepherds discovered a cave sealed with boulders where, after entering, he found an antique jar holding pieces of parchment. News of the first discovery led to researchers scouring the caves of Qumran for more manuscripts. Between 1949 and 1956, hundreds of manuscripts and thousands of fragments surfaced from expeditions to Qumran. This included the oldest relatively intact biblical manuscripts thus far found. Some of the manuscripts have been dated to the fourth century b.c.e.—potentially less than a hundred years after the Hebrew Bible was completed.

In its Roman galleries, the Ashmolean has one of the jars from Qumran on display. It originally sat in Jerusalem’s Palestine Archaeological Museum, today the Rockefeller Archaeological Museum. The Ashmolean purchased the jar in 1951 for £50.

In The Jewish Journey, Rebecca Abrams writes: “On 26 November 1951 a box containing an unspecified ‘jar’ was loaded onto an Air France flight from Jerusalem to London. The precious delivery arrived in Oxford on 6 December. The jar, however, was in pieces, as Donald Hardenm, then Keeper of Antiquities at the Ashmolean, pointed out, somewhat grumpily, a few weeks later: ‘The jar and its cover arrived some time ago. It was not too well packed and some of the recent mends had broken again … As you know, I always felt the price was excessive, and now that we have it in our possession, I am afraid I feel it all the more, but I did it out of kindness.’

“Today, the price looks more like a bargain. The jar was finally put back together in 2013 and in 2017 went on display for the first time.”

The Bible in the Heart of England

It is no exaggeration to state the work of the University of Oxford has changed Western civilization. England has had the prestigious reputation of being Europe’s educational center for hundreds of years. Without Oxford, many of England’s greatest scientific discoveries, literary works and political developments may have never happened. The politicians, explorers, archaeologists and chroniclers that helped build the largest empire known to man probably could not have accomplished what they did without the educational culture that institutions like Oxford cultivated.

It is fitting then that at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum are so many testimonies of the book that, in many ways, sits at the heart of Western civilization. The University of Oxford does not subscribe to the Bible as infallible truth, but it houses millenniums-old texts that point to the Bible—a book at the heart of Western civilization’s foundation.

The artifact Abrams first addresses in The Jewish Journey is the Sumerian King List, an object written by a pagan people on the other side of the Middle East, hundreds of years before the people of Israel existed. Abrams explains why she began her book there, writing:

“All stories are journeys, and all journeys begin with a departure. From a biblical perspective, the Jewish journey begins 4,000 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia. … [It] was from here that Abraham, the first great leader of the Jewish people and the founder of Jewish monotheism, set out for the land of Canaan. It was also here, at around the same time, that the Sumerian King List was made.”

The civilization that started with Abraham from Ur of the Chaldees has shaped the world. The science and culture developed at Oxford through the centuries has also had a significant role in shaping Western civilization. It still does. But behind the university’s current cutting-edge research and development taking place in modern buildings of glass and concrete sits an institution that points back to where it all began: a civilization from thousands of years ago, with stories of a flood, Passover, pharaohs and patriarchs—and the book that preserved them.