One of the most shocking events in the history of the biblical nation of Judah was the untimely death of one of its most righteous leaders: King Josiah. After assuming the throne at 8 years old in 640 b.c.e., he began leading the people in a revolution against the idolatrous worship practices of his father. In 622 b.c.e., those repairing and cleaning the temple discovered a copy of the law. Josiah was struck by the importance of its discovery and doubled down on the national repentance. In response, the Prophetess Huldah said the nation would not fall while the king was alive. This would have been welcome news considering Josiah was only 26 years of age and no doubt decades of peace remained ahead.

And yet, less than 15 years later, Josiah was dead in what seemed to be the most unnecessary of circumstances: battling the Egyptians at Megiddo, a location far outside the territory of Judah.

Now, thanks to a new archaeological discovery in Tel Megiddo, new evidence has surfaced supporting the biblical context for Josiah’s demise.

Megiddo’s Area X

Tel Megiddo is eye-catching. A massive raised city mound, it stands out in the middle of the vast, flat expanse of the Jezreel Valley. It is one of the largest ancient cities within Israel, with an extended city expanse beyond the mound itself, giving a total size of about 505 dunams (125 acres). Located along a vital trade route that cut through the Carmel Ridge, Megiddo controlled whatever passed through from Egypt to Mesopotamia or back the other way. It is the only site within Israel referred to by every single ancient major power in the Near East.

The city’s 26 different layers of occupation lead many to believe it has witnessed more battles than any other city in history. And so it was in King Josiah’s time that Megiddo once again saw a fateful skirmish: “In his days Pharaoh Necho king of Egypt went to the aid of the king of Assyria, to the River Euphrates; and King Josiah went against him. And Pharaoh Necho killed him at Megiddo when he confronted him. Then his servants moved his body in a chariot from Megiddo, brought him to Jerusalem, and buried him in his own tomb …” (2 Kings 23:29-30; New King James Version).

Until very recently, excavations at Megiddo had not yielded a single structure that could be conclusively dated to the time of the epic last stand of Josiah described in the Bible—the late seventh century b.c.e.

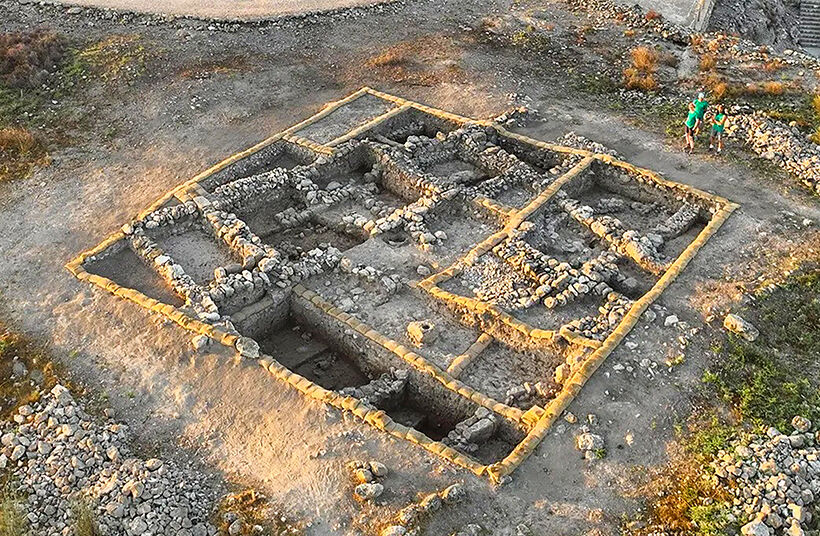

Excavators from the Megiddo expedition went to the northwestern sector of the mound and opened “Area X” in hopes of finding the elusive period represented. Excavations took place in this area in 2016, 2018 and 2022 under the supervision of Assaf Kleiman of Ben Gurion University of the Negev. The excavation directors were Prof. Israel Finkelstein and Dr. Matthew J. Adams. Results were recently published in part in an article titled “Josiah at Megiddo: New Evidence From the Field” (Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament).

According to the report, six layers were revealed in this area that date to the late phase of Iron iib to early Iron iic (late eighth to sixth centuries b.c.e.). The earliest of these layers belonged to the Assyrian destruction of Israelite Megiddo that took place in 732 b.c.e. The next two layers featured domestic remains dating from the late eighth/seventh century b.c.e. Following this, a new building (named Building 16) was constructed in the late seventh century, correlating to the time of King Josiah’s reign over Judah.

The fact that the team found a new building constructed at the time was important in itself, as it was documented evidence of a continuation of habitation at Megiddo through this period. But this is hardly surprising given Megiddo’s strategic importance.

What was surprising was the type of material culture found in Building 16, particularly the types of pottery.

Although there was a continuation of the forms produced locally, excavators found an overwhelming amount of vessels imported from Egypt. All totaled, they collected over 100 indicative pieces (such as rims), which amounts to the largest collection of Egyptian pottery ever discovered in the region. “No other site in the region has produced such a large quantity of Egyptian forms; in fact, the number of Egyptian items in seventh-century context in the southern Levant is negligible,” wrote Finkelstein and others.

And it just happens to be at the very site and at the very time of the confrontation of Josiah and the Egyptian army at Megiddo described in the Bible.

The excavators described the vessels as greenish in color and crude in design, rather than an exotic or expensive ware. Petrographic analysis of the Megiddo vessels show that they were made in Egypt, on both sides of the Nile River, from the edges of the Nile Delta as well as the area of Thebes in southern Egypt.

“When we opened the boxes of finds from the dig at my lab in Ben-Gurion University, I told my students to put the Egyptian pottery on the tables, and table after table got filled,” Dr. Assaf Keiman told Haaretz after their discovery. “The number of Egyptian vessels is double or even triple the amount found in the entire Levant for that period.”

According to Kleiman and Finkelstein, the low quality of the vessels indicates that they weren’t the subject of trade to a local but rather an indication of the presence of Egyptians themselves at Megiddo.

“This is not decorated fine tableware, so it’s very hard to argue that someone at Megiddo, a deportee or a surviving Israelite, all of a sudden acquired a taste for sub-par Egyptian pottery and decided to import it into his house,” Kleiman said. Finkelstein summarized: “The finds point instead to a steady stream of supplies from Egypt, most likely for Necho’s army.”

In the scientific paper, the authors opine that the best guess is that Building X was part of an “Egyptian administrative center with a garrison unit in the days of the 26th dynasty,” which includes Pharaoh Necho (who ruled from 610-595 b.c.e.).

The pottery, then, shows the Egyptians had a brief stint at Megiddo during the late seventh century b.c.e. The excavators also found numerous examples of imports from Greece, which they believe could indicate the use of Greek mercenaries in the Egyptian army, something in line with historical texts.

But curiously, there was also another outlier shard among the pottery in Building 16 from this period, which is perhaps indicative of a connection to Josiah’s kingdom. “Also noteworthy is a small fragment of a ridged Judahite-style cooking jug made of Moza clay [clay found almost exclusively in the area in and around Jerusalem], attesting to at least limited contact with seventh century b.c.e. Judah” (ibid).

So it’s all there in the archaeology of Building 16 of Area X in Megiddo. The Egyptians were dominant, but there was also a splash of evidence of Judah’s presence.

To get the larger context of those sherds, and perhaps the reason for Josiah’s presence so far north in the land of Israel, we turn to the Bible.

The Biblical Backstory

To understand the context of Josiah’s unexpected presence in Megiddo, we need to consider events of a century earlier.

In the mid-to-late eighth century b.c.e., the armies of the skin-shredding Assyrian Empire began to creep westward from their home base in northern Mesopotamia toward the Mediterranean and the Promised Land. Two centuries before that, the United Monarchy of Israel had split into two nations, with the northern territory retaining the name Israel and eventually building a new capital in Samaria. The southern kingdom retained Jerusalem as its capital city, and along with it, the Davidic dynasty of kings ruling over it. It would become known as the kingdom of Judah.

Thus, when Assyria ventured into the area, the nations of both Israel and Judah were confronted. The northern kingdom of Israel was first to suffer defeat after several waves of warfare led by Assyrian emperors Tiglath-pileser iii, Shalmaneser v and Sargon ii. This culminated in the three-year siege of Samaria in 721–718 b.c.e. and the deportation of the 10 northern tribes of Israel (2 Kings 18:9-11).

The next emperor, Sennacherib, ventured further south and attempted to take over Judah. His own annals describe the almost total destruction and subjugation of Judah. As the Bible relates, but for miraculous intervention by God, Jerusalem would have fallen; Judah would have gone into Assyrian captivity with her sister, Israel. Instead, the Davidic dynasty continued to rule from Jerusalem for almost another 150 years.

But what happened to the former Israelite territory? The book of Kings tells us: “… So Israel was carried away out of their own land to Assyria, unto this day. And the king of Assyria brought men from Babylon, and from Cuthah, and from Avva, and from Hamath and Sepharvaim, and placed them in the cities of Samaria instead of the children of Israel; and they possessed Samaria, and dwelt in the cities thereof” (2 Kings 17:23-24).

These new imports—ethnic Babylonians and others who themselves had been conquered by the Assyrians—brought with them their own customs and their own religious beliefs. And since they were in the land of Israel, they wanted to learn about (and thus appease) the god of the land of Israel. To accomplish this, these foreigners retrieved a priest from the ranks of the corrupted religious system of the Israelite tribes who taught them a corrupted version of the God of Israel—yet they retained many of their Babylonian customs. Centuries later, these people became known as the Samaritans. (More archaeological evidence of the Assyrian policy of importing foreigners to the region can be found in “Assyrian Deportation Policy at Tel Hadid”.) The Bible records that when King Josiah came to power in Judah, at least three or four generations of Samaritans were already living in the territory that was once held by Israel (Ezra 4:2).

What is interesting about the biblical account is that there is every indication that King Josiah was not satisfied with controlling just the territory of Judah, with its northern border about 20 kilometers north of Jerusalem. He began to encroach into Samaritan territory, otherwise known as the former territory of the northern kingdom of Israel. This was done as part of Josiah’s religious revival, routing pagan idolatry from the whole land of Judah, and then venturing north.

Both accounts in Kings and Chronicles confirm this. 2 Kings 23:19-20 state: “And all the houses also of the high places that were in the cities of Samaria, which the kings of Israel had made to provoke the Lord, Josiah took away, and did to them according to all the acts that he had done in Beth-el. And he slew all the priests of the high places that were there, upon the altars, and burned men’s bones upon them; and he returned to Jerusalem.” These altars and high places of the cities of Samaria were not in the southern kingdom, nor even under the control of Israelites at this time. Nevertheless, Josiah went to work removing them.

The Chronicles account is even more specific about how far north Josiah went in his purge: “And he burnt the bones of the priests upon their altars, and purged Judah and Jerusalem. And so did he in the cities of Manasseh and Ephraim and Simeon, even unto Naphtali, with their axes [or regions] round about. And he broke down the altars, and beat the Asherim and the graven images into powder, and hewed down all the sun-images throughout all the land of Israel, and returned to Jerusalem” (2 Chronicles 34:5-7). Again, at the time this took place, in the late seventh century, the northern kingdom of Israel was long gone. Yet the chronicler states that Josiah exerted his dominance all the way to Naphtali, whose tribal lands went northward past the Jezreel valley and through to the Upper Galilee. If we are to believe the biblical text, this means Josiah was exerting dominance over almost the entire region of Israel and Judah west of the Jordan River—from Dan in the north to Beersheba in the south.

To some, it might sound fanciful for a late-seventh century Judean king to control most of the territory that the Bible ascribed to King David over 300 years earlier. But consider that Josiah’s reign coincided with the demise of the great Assyrian Empire. After dominating the area of Israel from the time of Shalmaneser v in the late eighth century b.c.e., Assyria had to withdraw from the region in the early years of Josiah’s reign as the burgeoning Babylonian powerhouse revolted against the Assyrians further east. By around 630 b.c.e., Assyria had fully exited the former territory of Israel, creating a power vacuum that it seems Josiah was all too ready to fill.

It is in this geographic context that the concluding act of Josiah at Megiddo takes place.

It wasn’t just the Assyrians who were worried about the Babylonians. Both secular and biblical history show that the Egyptians were also deeply concerned, to the point of sending troops to help the Assyrians fend off the Babylonian advance. Under the command of Pharaoh Necho, the Egyptian army ventured through the Promised Land to help Assyria in battle. This most likely meant that Necho brought his troops along the coastal plain of Israel and then followed the main route to northern Israel and on into Syria. This meant passing through Megiddo. At which point King Josiah tried to head him off.

“After all this, when Josiah had prepared the temple, Neco king of Egypt went up to fight against Carchemish by the Euphrates; and Josiah went out against him. But he sent ambassadors to him, saying: ‘What have I to do with thee, thou king of Judah? I come not against thee this day, but against the house wherewith I have war; and God hath given command to speed me; forbear thee from meddling with God, who is with me, that He destroy thee not’” (2 Chronicles 35:20-21).

In this account, Necho says that his army doesn’t intend to disturb the kingdom of Judah. This is almost an acknowledgment that the area of Megiddo doesn’t belong to Judah, so there is no need for Josiah to join the fray. Nevertheless, considering how far afield Josiah had gone into the former territory of Israel to exert his religious dominance, perhaps he thought it was also his responsibility to dominate the territory politically. Whatever the case, Josiah attempted to stop the Egyptian army from proceeding and picked a fight with the Egyptians.

“Nevertheless Josiah would not turn his face from him, but disguised himself, that he might fight with him, and hearkened not unto the words of Neco, from the mouth of God, and came to fight in the valley of Megiddo. And the archers shot at king Josiah; and the king said to his servants: ‘Have me away; for I am sore wounded.’ So his servants took him out of the chariot, and put him in the second chariot that he had, and brought him to Jerusalem; and he died, and was buried in the sepulchres of his fathers. And all Judah and Jerusalem mourned for Josiah” (verses 22-24).

And that mourning was justified.

As the chronicler wrote, Jeremiah the prophet then wrote a lament about Josiah’s death (verse 25). He wasn’t mourning only the loss of a righteous king but also what Josiah’s sudden death meant for the demise of the entire Judahite kingdom and for his beloved city of Jerusalem. That same year, the mighty Babylonians would conquer both the Assyrians and Egyptians in battle. A few years later, Babylonians would pass by Megiddo en route to besiege that lone city on a hill—far sooner than any had expected.