On our most recent excavation, one of our volunteers had the motto: “Excavation is education.” It became her daily refrain. And while the consistency and rhythm of her phrase brought chuckles from the other volunteers, she is exactly right.

When we conduct an excavation, we expect to learn something about the site. Why else would we be digging? That’s one of the wonderful things about archaeology: You are constantly being educated; every day is an opportunity for discovery. It might not be something groundbreaking (no pun intended), but you will be provided with fresh information.

As we sift through the layers of earth, we collect material that can be used to date a site or explain its function. We often come across pottery sherds, coins or, on occasion, bullae. These are all important discoveries and certainly have their place in fulfilling the goal and purpose of each excavation. But as the late Dr. Eilat Mazar would remind those working on her excavations, what we’re most interested in discovering are the structures—the ancient walls that illustrate exactly how that particular area functioned.

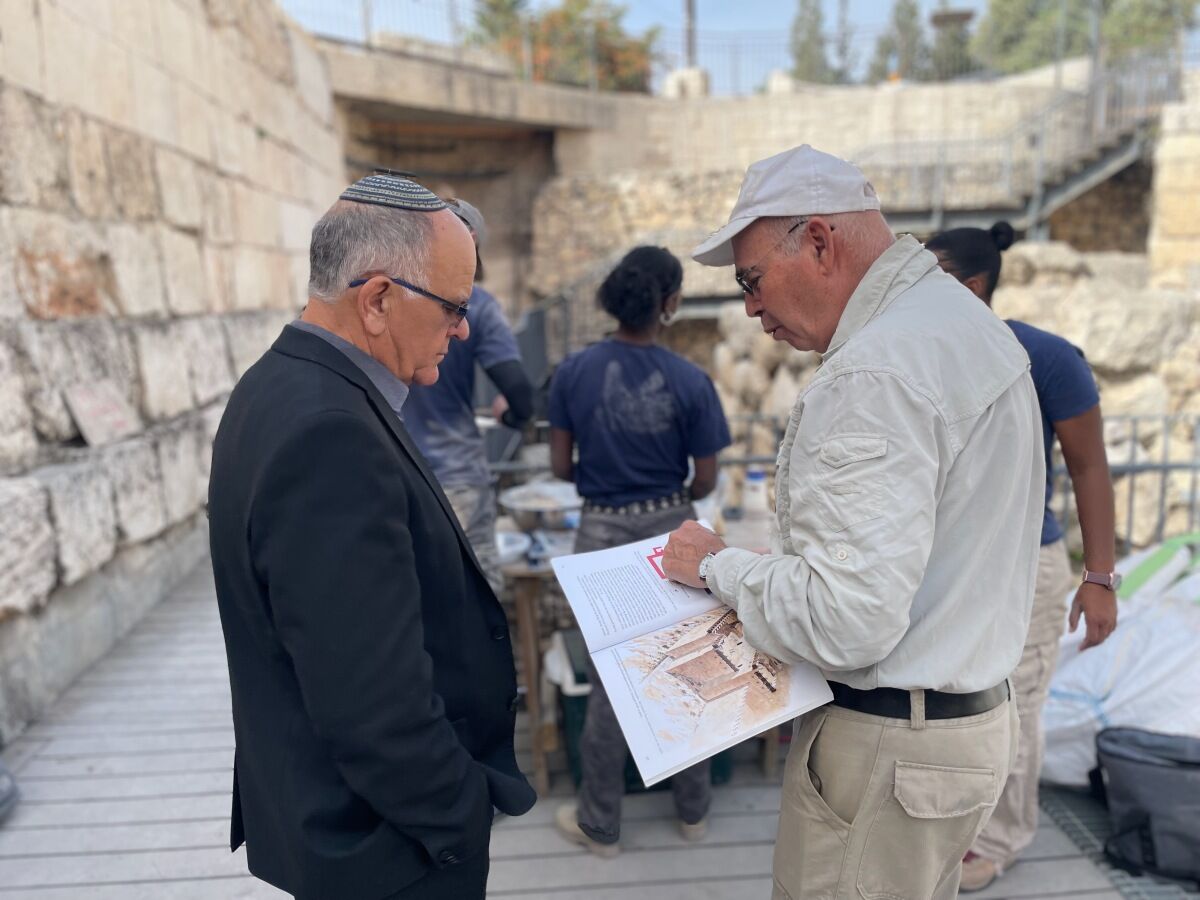

Our site this year is a perfect example of how the stones of a monumental structure speak. We learned a lot during our April season at the Ophel. It was unique: We excavated an area that has been untouched since 2010 and with a director we’ve never worked with in the field.

We went into the excavation with specific goals of what we wanted to accomplish. We had questions that we wanted answered. And while we did receive answers, the purpose of this article is not to get into all the specific findings from our excavation. We’ll first publish what we discovered in a scientific report in an academic journal. After that, we’ll publish the material in a popular format in this magazine.

For now, we’ll take a brief look at the history of the site and some of what we accomplished.

Site History

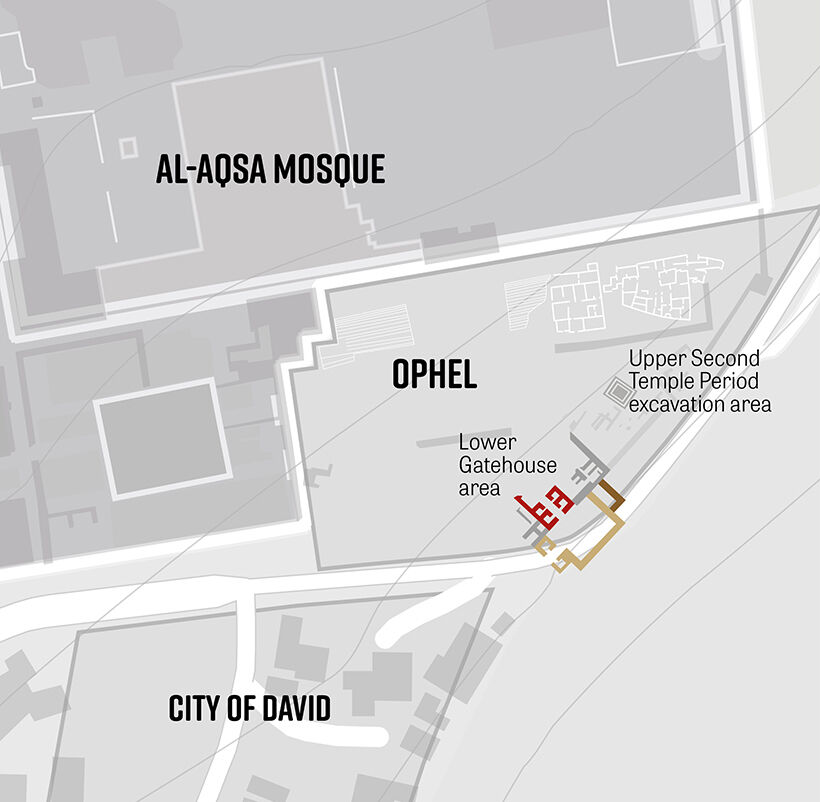

Most of our readers would be familiar with our Second Temple Period Ophel site that we excavate each summer with Prof. Uzi Leibner and Dr. Orit Peleg-Barkat. Perhaps most, however, are not familiar with the lower Ophel site (see map). Yet this was the first site we excavated with Dr. Mazar when we moved from the City of David to the Ophel in 2009.

This is an important area of the Ophel because of what Prof. Benjamin Mazar and Dr. Mazar discovered while working there from 1986 to 1987: “About 90 meters south of the Triple Gate in the southern wall of the Temple Mount compound, a monumental structure from the First Temple Period was uncovered by Benjamin Mazar. … Though only partially excavated, its highly skilled, sophisticated construction made it clear to Mazar that this was a royal structure,” Dr. Eilat Mazar wrote in her book Discovering the Solomonic Wall in Jerusalem. “[O]ur own excavations at the site in 1986–1987 revealed that the structure was in fact a gatehouse incorporated into the First Temple Period fortification line.”

In 2009, Dr. Eilat Mazar returned to the site with some of our own volunteers from Herbert W. Armstrong College to further excavate the gatehouse area. Adding the discoveries from that dig to what was found in 1986–1987, she had enough evidence to date the gate complex to the 10th century b.c.e.—the time of King Solomon.

While Dr. Mazar was confident that the Iron Age structure was a gatehouse, there has been some debate about its exact function.

That’s where this year’s excavation comes in.

Working With Purpose

Along with the City of David, the Ophel is one of the most important locations in Jerusalem—and really, one of the most important locations in all of Israel. After Solomon expanded the borders of Jerusalem outside the City of David, the Ophel became the administrative center for the nation. That means a lot of important history happened at this site.

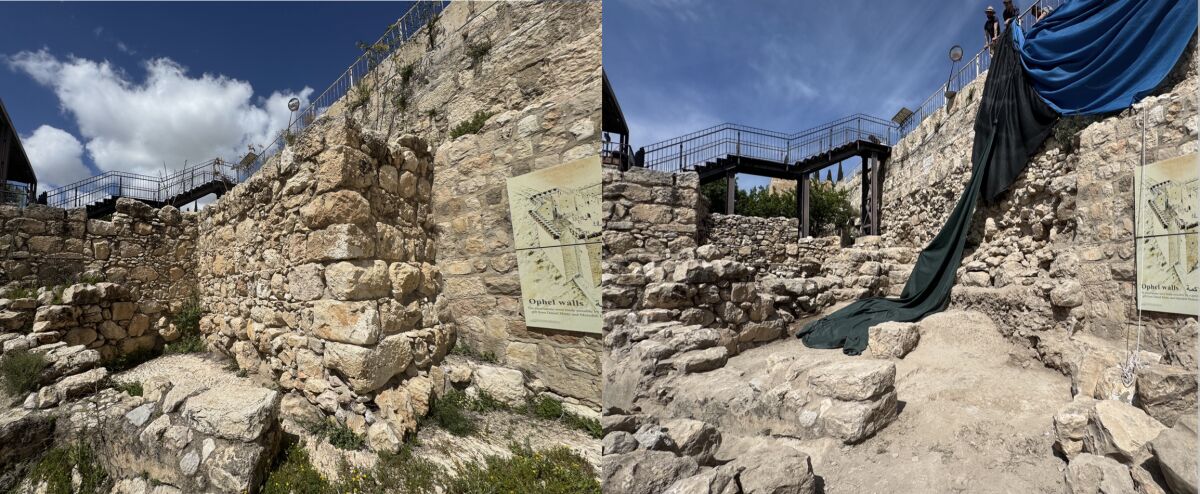

That also means it was a key target of Nebuchadnezzar’s 586 b.c.e. destruction of Jerusalem—an event that destroyed the city’s most important structures. Combine that with the fact that, over the centuries, later period infrastructure was built on top of the First Temple Period remains, and you have a conglomeration of Herodian, Byzantine and Muslim walls that obscure what is left of the Iron Age city. This was the case with our Iron Age gatehouse.

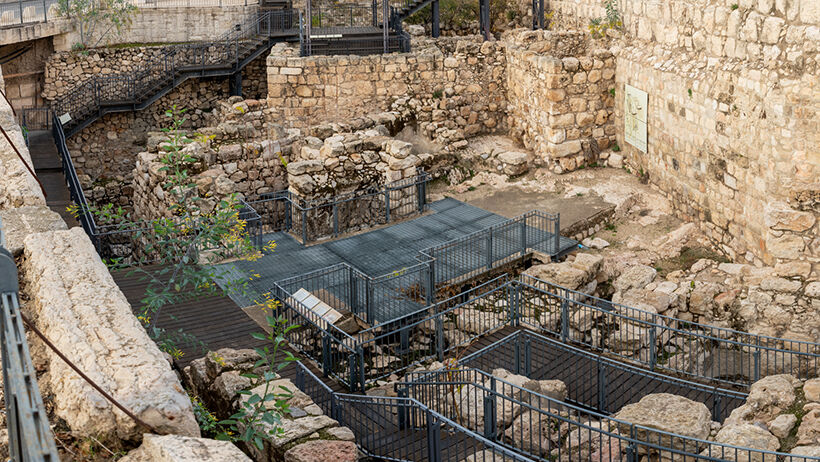

To those who knew which walls belonged to which period, the general structure of the gatehouse was obvious. But for those visiting the site for the first time, the whole area was unclear, a confusing labyrinth of walls and bedrock.

The purpose of our April 2025 excavation was to remove later-period remains—mostly Byzantine and Second Temple Period—and reveal the Iron Age remains around the gatehouse. The later-period remains are thoroughly represented elsewhere on the Ophel, but it is only here in the eastern Ophel where First Temple Period walls are preserved.

This excavation was part of a larger project we are conducting in partnership with the Israel Antiquities Authority, the Berkman-Mintz family, Hebrew University, East Jerusalem Development Ltd. and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. As Let the Stones Speak managing editor Brad Macdonald outlined in his January-February 2025 article “Another Year of Growth!”, the goal of this project is to develop the Ophel into a tourist-friendly destination, with clear and visually appealing signage, pathways and infrastructure.

As it is now, most people overlook this site because it is unclear what they are looking at. During our excavation, however, we had many visitors. People walking to the City of David or the Old City would stop, look down into our site, and ask questions; they were curious about where we were working! Some certified tour guides who stopped by said they knew nothing about the site, but after having it explained to them, they were amazed by what it contains.

We want to make it so anyone interested can understand and appreciate this important but often overlooked location. To do that, however, we first had to reveal the First Temple Period remains.

What We Did

Between April 2 and 27, nine volunteers worked on the site. The tasks varied day to day. Some were assigned to clean up the years’ worth of trash accumulation; others cleared away overgrown vegetation. The main priority was removing later-period walls and preparing the site for conservation.

This was a labor-intensive process that involved rolling stones off the top of a wall, which in some areas was 10 feet tall, onto sandbags below. The stones were then collected into one primary spot where they can then be used by conservationists to reconstruct the Iron Age structure to the highest preserved height. By the end of the excavation, we ended up with dozens of massive stones. We didn’t count the exact number, but Professor Garfinkel estimates we removed 300 tons of stones.

While there wasn’t as much unearthing involved in this dig, we still collected nearly 4,000 pottery sherds. These sherds represent many different periods—Iron Age, Roman, Byzantine and Crusader.

We’re very grateful to each of the volunteers who worked very hard over the course of the excavation to make it an incredible success. The work wasn’t easy, but each person approached every day eager to help wherever needed.

What’s Next?

Conservationists with the Israel Antiquities Authority are now working on rebuilding the Iron Age gatehouse structure to the highest preserved height. Soon, when tourists visit the site, it should be very clear what they are looking at.

We are eager to tell you more of what we learned about the gatehouse and to present this site to the general public for touring. The Ophel truly is a special location that deserves the attention it is finally receiving.

We’ll be back at our normal site this summer with Professor Leibner and Dr. Peleg-Barkat. Until then, stay tuned for more exciting updates to come!