The Prophet Jeremiah lived in Jerusalem in the late seventh and early sixth centuries b.c.e. and was in the city when it fell to King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon in 586 b.c.e.

In his book, the prophet identifies several Judean princes and court officials, all of whom either lived in Jerusalem or visited Judah’s capital. Among the Judean princes and officials listed by Jeremiah are Jehucal son of Shelemiah (Jeremiah 37:3), Gedaliah son of Pashur (Jeremiah 38:1), and Gemariah son of Shaphan (Jeremiah 36:10). Each of these individuals has been corroborated by archaeology.

However, in addition to mentioning the names of several Judean officials, Jeremiah also records the names of several Babylonian officials. “In the eleventh year of Zedekiah, in the fourth month, on the ninth day of the month, a breach was made in the city. Then all the officials of the king of Babylon came and sat in the middle gate: Nergal-sar-ezer of Samgar, Nebu-sar-sekim the Rab-saris …. Then Nebuzaradan, the captain of the guard, carried into exile to Babylon the rest of the people who were left in the city …” (Jeremiah 39:2-3, 9; English Standard Version). These three men were part of Jerusalem’s final moments—even sitting within one of its gates. They played an intimate role in the city’s dramatic collapse, but were they real?

The answer is, yes: Each of them has been revealed in Babylon’s archaeology. Names, titles and dates all match what is given in the Bible.

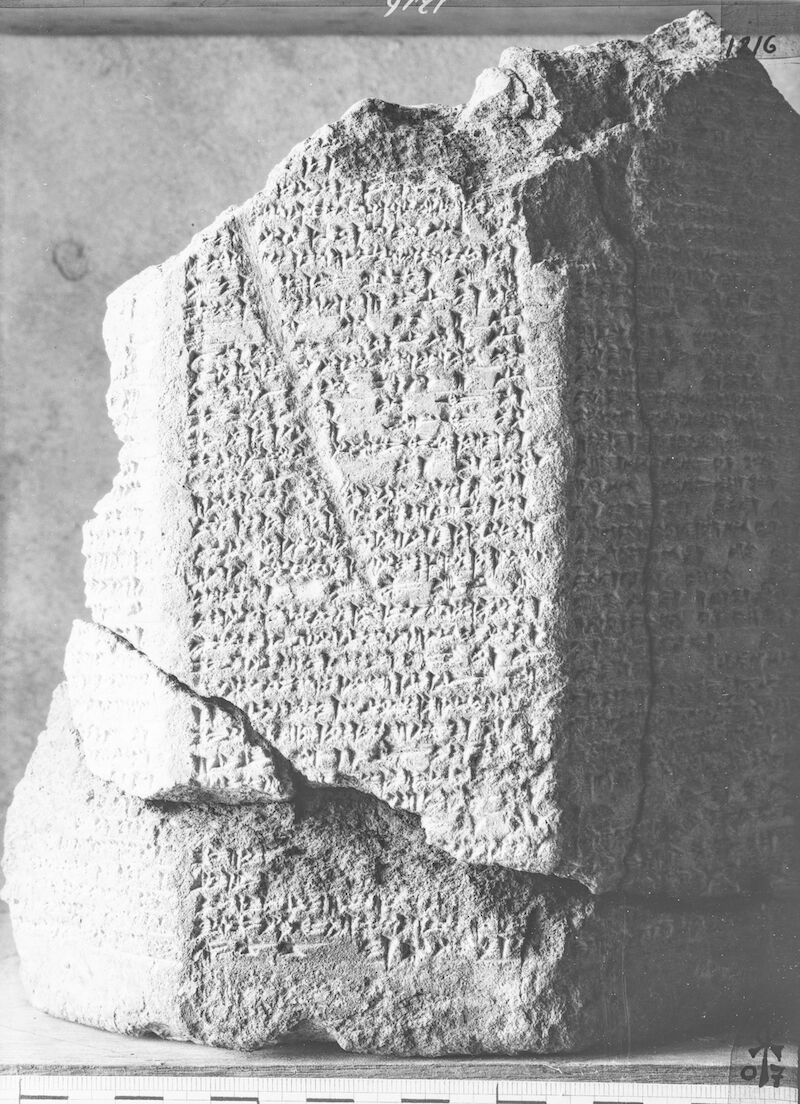

Regarding the first official mentioned in Jeremiah 39, Prof. Shalom E. Holtz wrote that his title Samgar “is likely the Akkadian word, simmagir, which, in the Neo-Babylonian period, was a title for a high official” (“The Babylonian Officials Who Oversaw the Siege of Jerusalem,” 2018). This high official is mentioned on the Nebuchadnezzar ii Prism (EK 7834), which was discovered in archaeological excavations in Babylon in the early 1900s. This Babylonian court document written around 570 b.c.e. lists more than 50 Babylonian officials, including “Nergal-sarru-usur, the simmagir.” This individual matches well with the Samgar of the Bible.

“This would be exactly equivalent to the information in Jeremiah 39:3, with the name Nergal-sar-ezer/Nergal-šarru-uṣur, followed by the title samgar/simmagir,” wrote Professor Holtz.

The next official mentioned in Jeremiah 39 is Nebu-sar-sekim the Rab-saris.

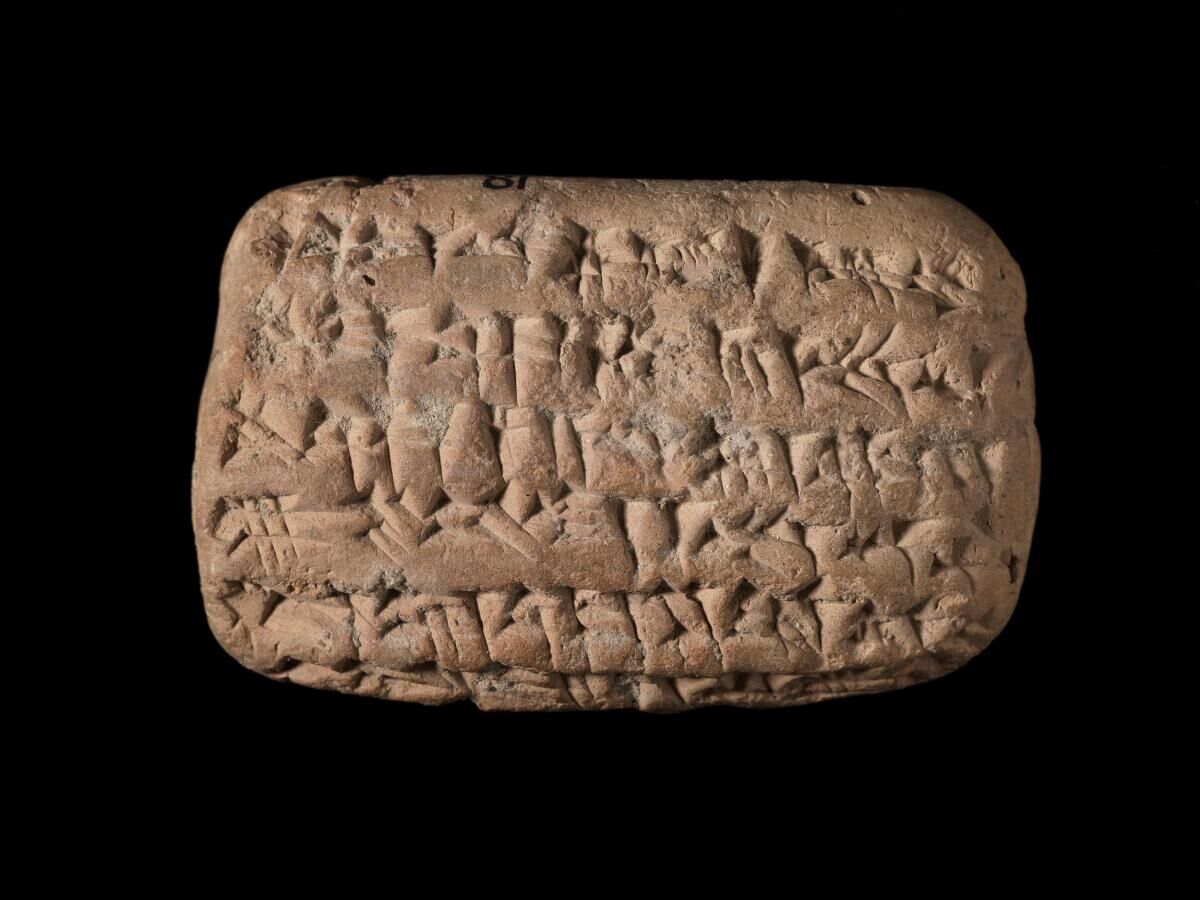

In 1920, antiquities trader Ibrahim Élias Géjou sold a unique tablet to the British Museum. This tablet (Tablet bm114789) has 11 lines of Akkadian cuneiform text and records a business transaction with an important figure: “1.5 minas (0.75 kilograms) of gold, the property of Nabu-sharrussu-ukin, the chief eunuch, which he sent via Arad-Banitu the eunuch to [the temple] Esangila …. Month xi, day 18, year 10 [of] Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon” (translation from the British Museum).

The name Nabu-sharrussu-ukin is the Akkadian form of Jeremiah’s Nebu-sar-sekim. This match went unnoticed until the tablet was reviewed in 2007 by Prof. Michael Jursa, who was cataloging Babylonian officials from cuneiform tablets. In a press release about the discovery, the British Museum said it was “a breakthrough for biblical archaeology—dramatic proof of the accuracy of the Old Testament” (The Times of London, July 11, 2007).

According to Semitic studies professor Lawrence Mykytiuk, this tablet dates to 595 b.c.e., a decade before the character is mentioned in the book of Jeremiah (around 587–586 b.c.e.).

Beyond the matching name and chronology, the title of this character has also been verified. Bryan Windle wrote, “His title, the Rab-saris, is identical to that in the biblical text (rab ša-rēši, chief eunuch in Akkadian)” (“Top Ten Discoveries Related to the Book of Jeremiah,” 2024).

This is a remarkable synchronization of the biblical text and Babylonian history. “The extreme unlikelihood that two individuals having the same personal name would have been the sole holders of this office, and within a decade of each other, makes it safe to assume that the inscription and the book of Jeremiah refer to the same person in different years of his time in office,” wrote Mykytiuk in “Eleven Non-Royal Jeremianic Figures Strongly Identified in Authentic, Contemporaneous Inscriptions” (Eretz Israel, 2016).

The next Babylonian official mentioned in Jeremiah 39 to be confirmed through archaeology is “Nebuzaradan the captain of the guard.” He led the final siege against Jerusalem (2 Kings 25:8) and organized the deportation of the remaining Jews to Babylon (Jeremiah 39:9). He is also the official who spoke to Jeremiah and allowed him to go free on the orders of King Nebuchadnezzar ii. The biblical text shows that he was the trusted assistant of the Babylonian king.

Nebuzaradan is also named on the previously mentioned Nebuchadnezzar ii Prism. On the prism, the name is recorded as “Nabû-zeru-idinna rab nuḫatimmi.” Nabû-zeru-idinna is the Akkadian equivalent to the Hebrew Nebuzaradan. Rab nuḫatimmi is a term sometimes translated as “the chief cook” but can mean something nearer to “the chief cupbearer.” It’s a name that implies he was deeply trusted by the king, as the Bible portrays.

Bible scholar Matthijs De Jong wrote that “the title of chief cook does not mean that this man cooked the king’s meals. It rather denotes a high royal functionary, someone trusted by the king, who could, as we see from the biblical texts, be entrusted with an important responsibility.” The name, chronology and function of these two mentions are all a strong match.

The discovery of archaeological evidence of three Babylonian officials from the book of Jeremiah is remarkable. It demonstrates that the book of Jeremiah accurately records history—down to the very names and titles of Judean and Babylonian officials involved in the destruction of Jerusalem.

After calling the Nabu-sharrussu-ukin tablet “a fantastic discovery” and “world-class find,” Irving Finkel, an assyriologist and curator at the British Museum, asked: “If Nebo-Sarsekim existed, which other lesser figures in the Old Testament existed? A throwaway detail in the Old Testament turns out to be accurate and true. I think that it means that the whole of the narrative takes on a new kind of power.”