Fires raged. Weapons littered the ground. People mourned. A once vibrant, peaceful city sat in utter ruin. The timeless lesson of cause and effect was on full display.

The reason for Jerusalem’s destruction, as it is recorded in the biblical text, is simple: Obedience brought prosperity and peace; disobedience brought destruction and suffering. This was a cycle that played out time and again in biblical history. Just over 100 years before, during the reign of King Hezekiah, Jerusalem had been spared complete destruction at the hands of King Sennacherib and the Assyrian army.

But by the late seventh b.c.e., there was no escaping the coming tragedy. The destruction of Judah and its magnificent capital—including the first temple—was assured. In this article, we will consider the archaeology attesting to Jerusalem’s dramatic fall to the Babylonians. First, let’s look at what biblical history records about this seminal event.

The Biblical Background

Under the leadership of King Manasseh (697–642 b.c.e.), the people descended into paganism and idolatry. Such rank rebellion only a few years after the nation was spared from being crushed by the Assyrian army meant unparalleled destruction was on the horizon.

The Bible documents God’s stern warning: “‘Because Manasseh king of Judah hath done these abominations, and hath done wickedly … and hath made Judah also to sin with his idols: therefore thus saith the Lord, the God of Israel: Behold, I bring such evil upon Jerusalem and Judah, that whosoever heareth of it, both his ears shall tingle. … [T]hey shall become a prey and a spoil to all their enemies; because they have done that which is evil in My sight, and have provoked Me, since the day their fathers came forth out of Egypt, even unto this day’” (2 Kings 21:11-15).

Judah’s fate was sealed: The nation would be destroyed and the people taken into captivity. Then came King Josiah. This king was the antithesis of Manasseh. When a copy of the law was discovered in the 18th year of Josiah’s reign (around 623 b.c.e.), the king humbled himself and led Judah in national repentance. This act of humility moved God to make a merciful promise: Judah would not be destroyed until after Josiah’s death. The punishment had been delayed, but the countdown had started.

The people relaxed. Josiah had been crowned when he was only 8 years old, and he was around 25 when this promise was made. Everyone expected Josiah to live a long life; thoughts of the nation’s inevitable destruction were out of sight and out of mind.

Then the unexpected happened: Josiah was killed in a battle against Egypt at just 39 years old.

After Josiah’s death, the Prophet Jeremiah wrote the book of Lamentations. The Talmud describes this book as a kinot, or a funeral dirge. It was representative of how the people lamented the death of Josiah, knowing what would befall the nation. “Jeremiah wrote the book of Lamentations when Judah had reached the point of no return,” writes Let the Stones Speak editor in chief Gerald Flurry. The timer had gone off—the coming siege by a foreign power was certain and inescapable.

Although Judah did not completely collapse for nearly 23 years, they were difficult years of conquest and subjugation. It didn’t help that Judah was led by lame duck kings who only exacerbated the nation’s woes.

Josiah’s son Jehoahaz reigned for three months before being taken captive by Egypt. Egypt considered Judah a tributary and set up Eliakim, Josiah’s older son, as king. Pharaoh Necho changed his name to Jehoiakim. During the reign of this king, the prophecy in 2 Kings 21 began to take shape.

The biblical account of Judah’s destruction is detailed and dramatic. But is it supported by science? In fact, a significant amount of archaeological evidence proves not only Judah’s destruction in the late seventh and early sixth centuries b.c.e., but also what led up to that destruction.

The First Siege

Egypt and Assyria were the dominant regional powers in the ninth and eighth centuries b.c.e. This changed in 605 b.c.e., when Babylon defeated their combined armies at the Battle of Carchemish. This battle is remarkable because it is attested to in both the Bible (2 Chronicles 35:20; Jeremiah 46:2) and archaeology (e.g. Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle). In this epic battle, Babylon defeated the Egyptian-Assyrian alliance and became the dominant regional power.

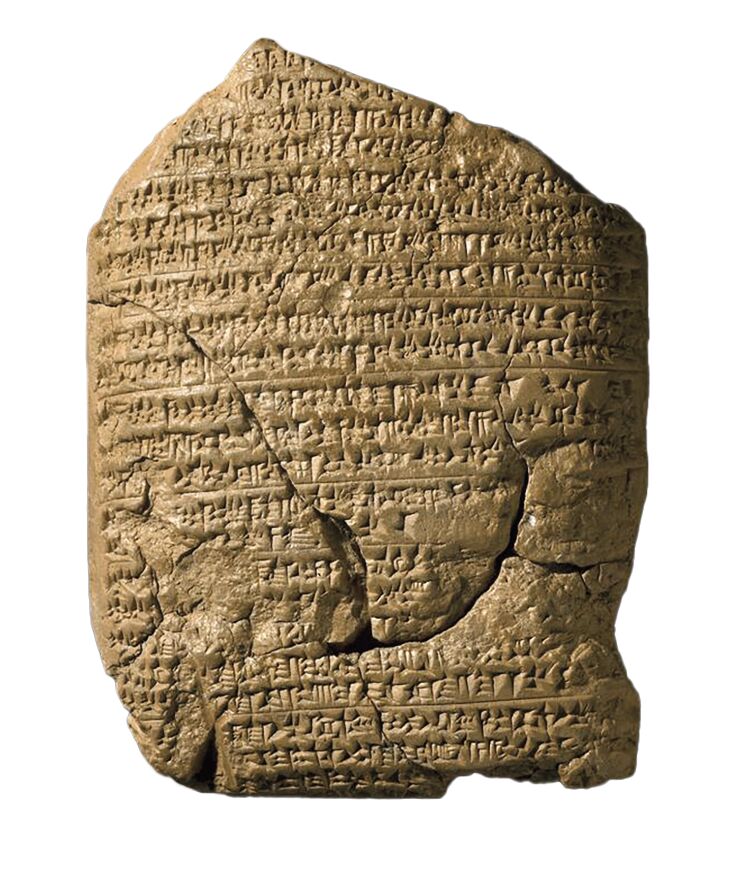

The details of this battle, including the names of the specific kings involved, are recorded on the Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle. This small inscription, discovered in 1896, is one of the Babylonian Chronicles. It provides details for the first 11 years of Nebuchadnezzar ii’s reign.

The tablet records that although Nabopolasser was the king of Babylon at the time of Carchemish, he stayed back and sent his son Nebuchadnezzar to lead Babylon into battle. Following the victory, Nebuchadnezzar received news of his father’s death and quickly returned to Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar ii’s ascension to the throne would have major consequences for Judah.

Judah was one of Egypt’s many tributaries in the region. Logically, Nebuchadnezzar’s first step after defeating the Egyptian army at Carchemish would be to make sure that each of these tributaries paid allegiance to Babylon.

The Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle records that in 604 b.c.e., Nebuchadnezzar “marched unopposed through the Hatti-land; in the month of Šabatu he took the heavy tribute of the Hatti-territory to Babylon.” “Hatti-land” and “Hatti-territory” refer to the region that includes Judah. Both the geography and chronology match the Bible’s description of Babylon’s first siege of Judah.

The book of Daniel records that around 604 b.c.e. Nebuchadnezzar marched into Jerusalem and took treasures from the temple; he also took the sons of the nobles and royal princes captive (Daniel 1:1-3). This was Babylon’s first siege of Judah.

At this time, Jehoiakim pledged his loyalty to Babylon. That commitment, however, was short-lived: “In his days Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon came up, and Jehoiakim became his servant three years; then he turned and rebelled against him” (2 Kings 24:1). After he stopped paying tribute to the empire, Jehoiakim was brought to Babylon and imprisoned (2 Chronicles 36:5-8). After 11 years, his reign over Judah ended.

The Second Siege

Jeconiah (or Jehoiachin) began reigning in Judah after his father was taken to Babylon. He reigned only three months before he was deposed during Babylon’s second siege.

The Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle records: “In the seventh year, the month of Kislîmu, the king of Akkad mustered his troops, marched to the Hatti-land, and besieged the city of Judah and on the second day of the month of Addaru he seized the city and captured the king.” This second siege took place around 597 b.c.e.

The text on the Babylonian chronicle aligns perfectly with the history recorded in 2 Chronicles 36:10. “[K]ing Nebuchadnezzar sent, and brought him [Jeconiah] to Babylon, with the goodly vessels of the house of the Lord …” (King James Version). Jeconiah was imprisoned in Babylon. (For more information on Jeconiah’s time in Babylon, read our article, “A Tablet, a King and His Rations.”)

But that is not all that Nebuchad-nezzar did during this second siege. Just as Pharaoh Necho did with Jehoiakim, Nebuchadnezzar put a king in place whom he believed would show him unconditional loyalty. This too is described on the Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle: “He appointed there a king of his own choice, received its heavy tribute, and sent to Babylon.”

Judah’s new king was Zedekiah. This king is most famous for his confrontations with the Prophet Jeremiah (see also “Jeremiah: The True Story of the ‘Weeping Prophet’”). But Zedekiah eventually stopped paying tribute to Babylon and formed an alliance with Egypt—two mistakes the Prophet Jeremiah had warned Zedekiah against. This enraged Babylon’s King Nebuchadnezzar, who set out to punish Zedekiah and destroy Judah once and for all.

Thus commenced the third and final siege of Judah.

The Third Siege

This was a troubling time for the nation. The prophesied destruction had come. City by city, Nebuchadnezzar’s forces conquered Judah. In addition to Jerusalem, the biblical text specifies that Nebuchadnezzar conquered two other fortified cities: Lachish and Azekah (Jeremiah 34:7). The fall of these two cities is dramatically revealed in archaeology.

In “Archaeology and the Fall of Judah,” Prof. William Dever wrote: “Level ii [at Lachish] witnesses a final, heavy destruction, undoubtedly in 586 b.c.e. Especially significant are the several ostraca found in the guardroom of the city gate at Lachish.”

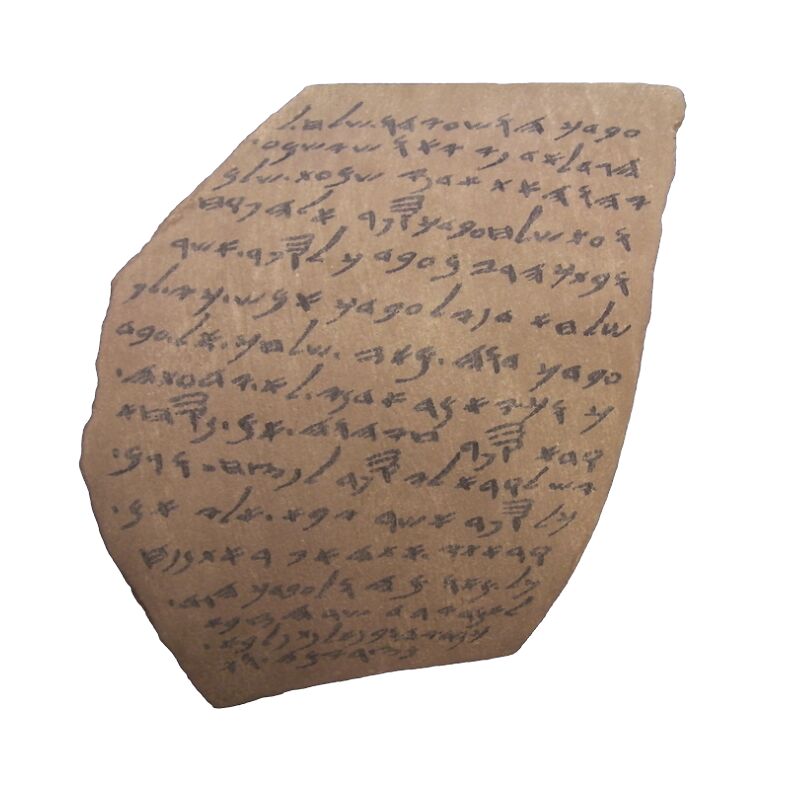

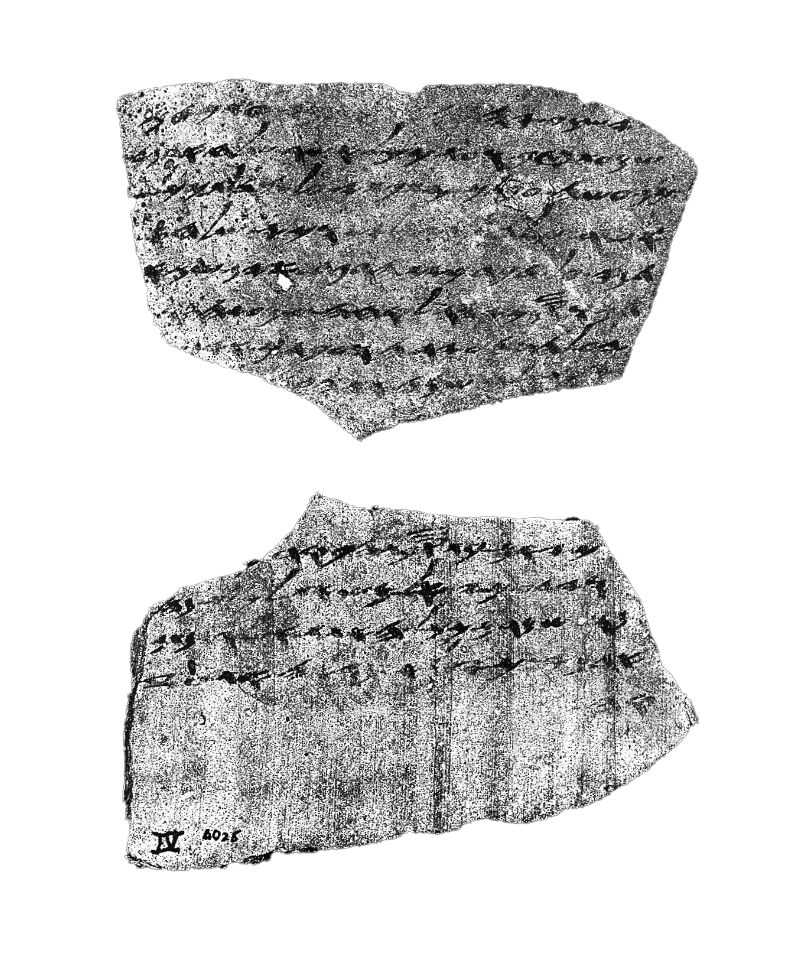

We know these ostraca as the Lachish Letters. “These important documents, written in an iron-carbon ink with a reed or wood pen, during the lifetime of the Prophet Jeremiah, in the early part of the sixth century b.c.e., are the first personal documents in pre-exilic Hebrew script found in Palestine,” Dr. Joseph Reider wrote in “The Lachish Letters.”

These letters were sent from a small outpost to Lachish. They were intended to provide the governor of Lachish with military and political information (ibid).

Letter iii is one of the most studied letters in the collection. It states: “The commander of the army, Coniah, son of Elnatan, has gone down to go to Egypt …. And as for the letter of Tobiah, the servant of the king, which came to Shallum, son of Yada from the prophet, saying ‘Beware!’—your servant has sent it to my lord.” This connects well with the account in Jeremiah 26:20-23, which describes Uriah the prophet giving a warning to Judah’s king but then fleeing to Egypt for safety; only to ultimately be sought by the king’s men and brought back to Judah. That event took place during the reign of Jehoiakim; however, these letters are recognized as being written during the reign of King Zedekiah.

Another possible interpretation is that the commander of Judah’s army was taking a contingent of men to Egypt to shore up an alliance, which the Prophet Jeremiah had warned Zedekiah against. The Prophet Ezekiel describes this in Ezekiel 17: “But he rebelled against him in sending his ambassadors into Egypt, that they might give him horses and much people” (verse 15).

Regardless of the exact interpretation of the letter, this is obvious archaeological evidence of a connection between Judah, Egypt and a prophet warning “Beware!”—all in the final days of Judah.

Letter iv has a clearer interpretation: “Then it will be known that we are watching the (fire) signals of Lachish according to the sign which my lord gave us for we do not see Azekah.” Azekah and Lachish were both hilltop fortresses; in the event of an invasion or threat, officials in these cities would light fire signals to communicate with the surrounding region. Jeremiah 6:1 mentions such a signal going up at this time (New King James Version). The fact that no signal was coming from Azekah indicates that it had already fallen—and Lachish was next.

The archaeological evidence at Lachish shows that in 586 b.c.e. it endured a city-wide conflagration; the destruction wasn’t limited to the gatehouse or fortress walls or perimeter of the city. Hebrew University professor Yosef Garfinkel has conducted several excavations at Lachish and is an expert on the site. He has written that deep within the walls of Lachish Level ii he and his team found “a massive layer of fire destruction.”

The fact that this destruction layer continued into the domestic portions of the city, far from the gate, is evidence “that the Babylonians destroyed the entire city by fire.”

In addition to the destruction layer left by the fire, Garfinkel’s team also discovered three Irano-Scythian arrowheads. This particular style of arrowhead was introduced into the region in the late seventh century b.c.e. and is known to have been used by the Babylonians on their campaigns.

Lachish was Judah’s second-most important city. It was a heavily fortified city and certainly a key focus of Nebuchadnezzar’s invasion. No city, however, was more important to Nebuchadnezzar’s plans of destroying Judah than the capital. His vengeful eyes were set on Jerusalem.

The Capital Has Fallen

One month after Nebuchadnezzar took the fleeing Zedekiah captive and killed his sons, he sent the captain of his army to Jerusalem to finish the razing of the city. “Now in the fifth month, in the tenth day of the month, which was the nineteenth year of King Nebuchadrezzar, king of Babylon, came Nebuzaradan the captain of the guard, who stood before the king of Babylon, into Jerusalem; and he burned the house of the Lord, and the king’s house; and all the houses of Jerusalem, even every great man’s house, burned he with fire. And all the army of the Chaldeans, that were with the captain of the guard, broke down all the walls of Jerusalem round about” (Jeremiah 52:12-14).

On the final day of his 1975 excavation in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem, Prof. Nahman Avigad discovered what was reported at the time to be the “first remains ever recovered of the two-year Babylonian siege which finally broke the defenses of the starving city” (“Found in Jerusalem: Remains of the Babylonian Siege,” Biblical Archaeology Review, March 1976). These remains, although monumental in importance, were some of the smallest artifacts you can find: arrowheads.

The four arrowheads were discovered under an ash layer at the base of a 2,600-year-old defense tower (ibid). One of these arrowheads was of the Irano-Scythian design.

In 2019, more of the same arrowheads were discovered during archaeological excavation of Mount Zion. Archaeologists discovered the arrowheads in the same context as a layer of ash, broken vessels, oil lamps and a piece of jewelry. Codirector and University of North Carolina–Charlotte professor Shimon Gibson said, “It’s the kind of jumble that you would expect to find in a ruined household following a raid or battle.”

The archaeologists were most excited about the unique jewelry piece they had discovered. It appears to have been an earring with a bell-shaped, gold upper portion, with a silver cluster of grapes below.

Regarding the ash layer, Gibson explained: “For archaeologists, an ashen layer can mean a number of different things. It could be ashy deposits removed from ovens; or it could be localized burning of garbage. However, in this case, the combination of an ashy layer full of artifacts, mixed with arrowheads, and a very special ornament indicates some kind of devastation and destruction. Nobody abandons golden jewelry, and nobody has arrowheads in their domestic refuse” (emphasis added throughout).

It appears the Mount Zion team is excavating within or around an Iron Age structure. While Gibson said, “I like to think that we are excavating inside one of the ‘great man’s houses’ mentioned in 2 Kings 25:9,” they have yet to excavate the building itself. Though the exact function of the Mount Zion structure is not yet known, we already have evidence of a monumental building that was destroyed during Babylon’s siege.

Building 100 Speaks

Nebuzaradan’s final siege against Jerusalem focused on destroying the city walls, the temple, the king’s palace and the houses of great men. In other words, the destruction of Jerusalem focused on wiping out the monumental structures.

One of these monumental structures has been discovered in Jerusalem’s Givati Parking Lot excavation: This is Building 100.

Archaeologists Prof. Yuval Gadot and Dr. Yiftah Shalev lead the excavation and wrote about this structure in Biblical Archaeology Review: “The Iron Age building [Building 100] recently excavated in the Givati Parking Lot section of the City of David was unique in Jerusalem’s ancient landscape. A magnificent residence and reception hall used for official ceremonies and social gatherings … reflecting the daily life of Jerusalem’s ruling elite at the end of the First Temple Period” (Spring 2024).

Building 100 is a two-story structure made of both ashlar stones and fieldstones; it is composed of three rooms (rooms A, B, C). According to a 2023 Journal of Archaeological Science report, “All three rooms were found filled with a thick layer of destruction debris, including large amounts of sediments, collapsed construction stones, artifacts and other architectural elements. … The significant presence of charred remains found in all three rooms clearly indicates that the destruction of Building 100 involved a large fire” that “was intentionally ignited ….”

Within the largest of the rooms, Room A, archaeologists discovered charred wooden beams, indicating that the roof had caved in due to the fire. Room C contained more charred wood pieces and finely crafted ivory inlays, both of which most likely came from furniture (see Amos 6:4).

The excavation team was able to date the destruction using the pottery found in the remains. Among the pottery, most notable were the rosette impressions on the storage jar handles. These impressions replaced the lmlk seals that were used during King Hezekiah’s reign. According to Israel Antiquities Authority excavation directors Ortal Chalaf and Dr. Joe Uziel: “These seals are characteristic of the end of the First Temple Period and were used for the administrative system that developed towards the end of the Judean dynasty.”

When all the evidence is put together, it’s obvious that Building 100 is one example of Babylon’s siege against Jerusalem—and its great houses.

Structural Evidence

Other structures in Jerusalem have been excavated that also point to a complete destruction at the hands of Babylon.

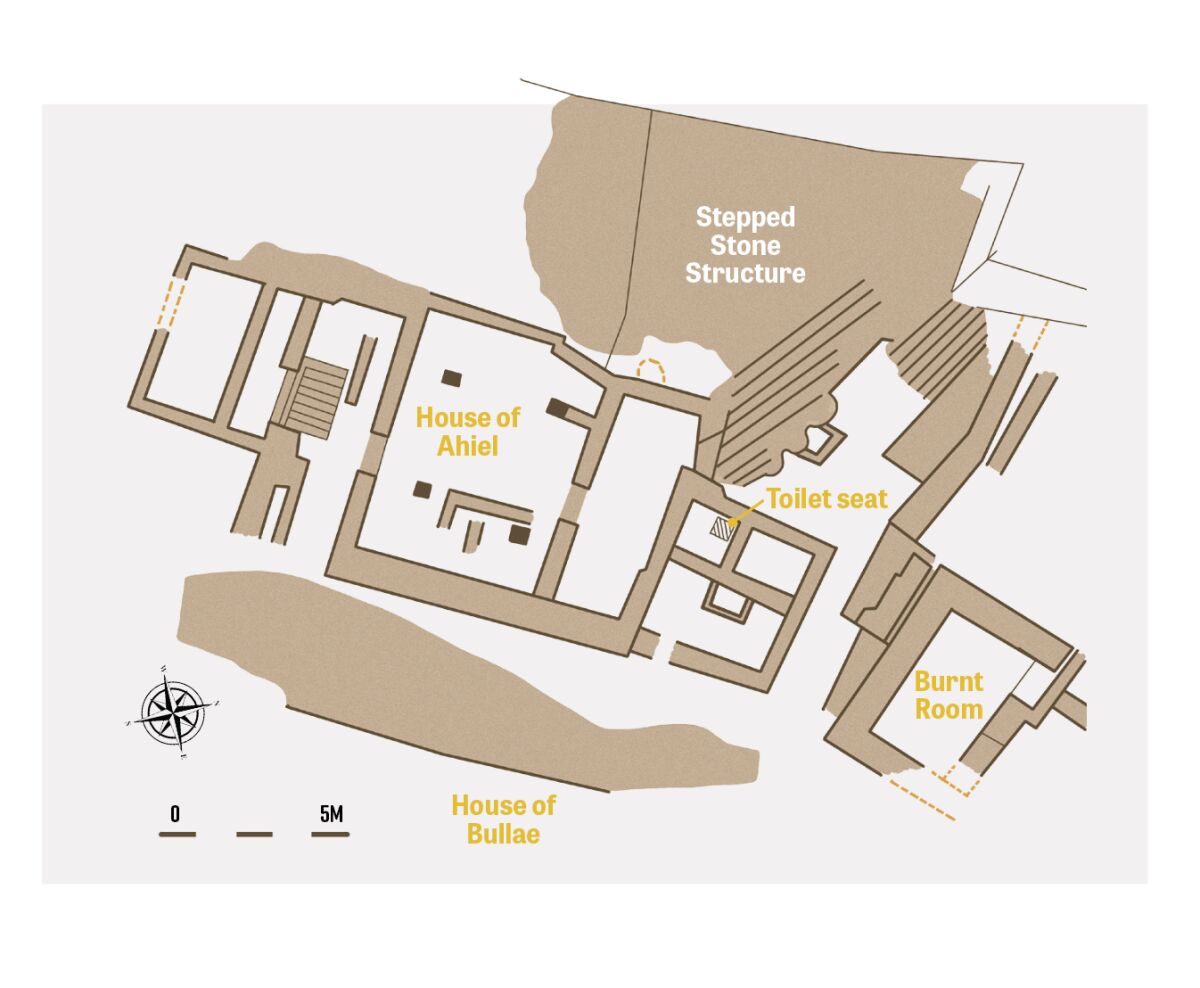

Within Stratum x of the City of David’s Area G (near the Stepped Stone Structure), Prof. Yigal Shiloh discovered three main structures: the House of Ahiel, the Burnt Room and the House of Bullae. According to Shiloh, the destruction of each of these “buildings was total. Prior to this there was a conflagration. The charred remains of wooden beams were found above the floors ….”

Within the Burnt Room and the House of Bullae, Shiloh discovered bronze and iron arrowheads, which he said “are indicative of the ‘war atmosphere’ in Jerusalem on the eve of its destruction.”

In Area E1, Shiloh discovered the Lower Terrace House and the Ashlar House. Both of these structures had destruction levels and evidence of fire. “A similar fate befell the city-wall for its entire length,” wrote Shiloh.

In each of these areas, Shiloh wrote that “[t]he evidence in the Bible … is complemented by the clear-cut archaeological evidence: the total destruction of the various structures and a conflagration which consumed the various wooden parts of the houses. … The atmosphere of war and destruction is emphasized by the quantity of weapons found scattered within various buildings ….”

When the late Dr. Eilat Mazar excavated the City of David between 2007 and 2008, her team discovered over 100 arrowheads. (To learn more about this crucial excavation, read our article, “Excavating Area G—a Time Capsule of Jerusalem’s Destruction.”)

At the Ophel, situated adjacent north of the City of David, the story is the same: During her excavations in this area, Dr. Mazar reached First Temple Period floors. In Area D, or the Royal Structure, “the first burnt floor layer began to appear. We discovered that it was not only ashes that remained on the floor, but also large pieces of broken pottery, obviously part of very large vessels that had been destroyed and burned where they stood” (Discovering the Solomonic Wall in Jerusalem).

These large vessels, or pithoi, could have stored wine, oil or date honey. As researchers restored the pieces, it became increasingly obvious that the vessels “had suffered the effects of an intense and prolonged fire, whose signs were pronounced even on the stones of the walls ….”

The structures on the Ophel and in the City of David paint the same picture: In the early sixth century b.c.e., the buildings were destroyed in a major conflagration—just as the Bible describes.

In 2021, archaeologists excavating the City of David discovered a large portion of the eastern fortress wall. The wall is 30 meters long, 2.5 meters tall and 5 meters wide and connects two previous sections of wall discovered by Dame Kathleen Kenyon and Professor Shiloh. While the wall itself did not show signs of destruction, a building attached to the wall had an ash layer and crushed pottery remains, including the telling rosette impression—evidence that it was clearly destroyed by a fire and collapsed in the sixth century b.c.e.

They also discovered a Babylonian seal against the wall. The seal bore depictions of Marduk and Nabu, two Babylonian gods. As the archaeologists explained, it’s possible it belonged to one of the soldiers, though we can’t know for sure. The inhabitants of Jerusalem were certainly steeped in pagan practices themselves—the very reason they went into captivity to begin with. But whether it belonged to a soldier or was a trinket of a Judahite, it represents a Babylonian presence in Jerusalem at this time.

The Vinedressers and Husbandmen

While it’s important to study the cities that were destroyed during the Babylonian siege, we can also learn a lot from what wasn’t destroyed. In studying destruction layers throughout Israel, William Dever came to the conclusion that “[t]he smaller towns, villages and rural areas were mostly not affected by the Babylonian takeover.”

This too fits with the biblical description of Nebuchadnezzar’s final siege against Judah. The Prophet Jeremiah wrote: “But Nebuzaradan the captain of the guard left of the poorest of the land to be vinedressers and husbandmen” (Jeremiah 52:16). This is exactly what we see from the archaeological evidence. According to Dever, Babylon took a “calculated” approach and targeted “the major centers,” leaving the countryside as a source of revenue for the empire.

One particular city Babylon left untouched was Mizpah. In fact, Nebuchadnezzar made Mizpah the new capital of the Judean province (2 Kings 25:23). He appointed a man named Gedaliah as governor over this province (Jeremiah 40:7-8). The archaeology of Tel en-Nasbeh, modern-day Mizpah, reveals that “[t]here is no destruction at the end of the Iron Age, and the site has major buildings of the sixth–fifth centuries b.c.e.” (ibid).

It’s remarkable to see the evidence of destruction within Judah—the burn layers, the arrowheads, the evidence of utter citywide conflagration. But it’s also remarkable to see the areas that were left untouched. “Jerusalem and the temple were violently destroyed; the Judean kingdom did come to a disastrous end,” wrote Dever. “Yet the remnant of the people left hope for an eventual reconstitution.”

Studying the evidence of Babylon’s siege against Judah puts cause and effect on full display. But it also gives cause for hope. God had promised the Jews through the Prophet Jeremiah that they would be permitted to return to Judah after 70 years of captivity. The vinedressers and husbandmen left behind were a reminder to the inhabitants of Judah that that promise would be fulfilled: They would return to their own land and rebuild the homes, the walls and the temple.

“And there is hope for thy future, saith the Lord: And thy children shall return to their own border” (Jeremiah 31:17).