Nebuchadnezzar ii is among the most eminent kings in history. He ruled over the Babylonian Empire when its territory spanned from the Nile River to the Persian Gulf. During his reign, he oversaw the construction of temples, ziggurats, palaces and gardens. Babylon was filled with unparalleled public works.

The Bible accurately reflects this Babylonian history. The Prophet Daniel described Nebuchadnezzar ii as the head of gold (Daniel 2:38)—a ruler and a kingdom to which all succeeding emperors and empires would be “inferior” (verse 39).

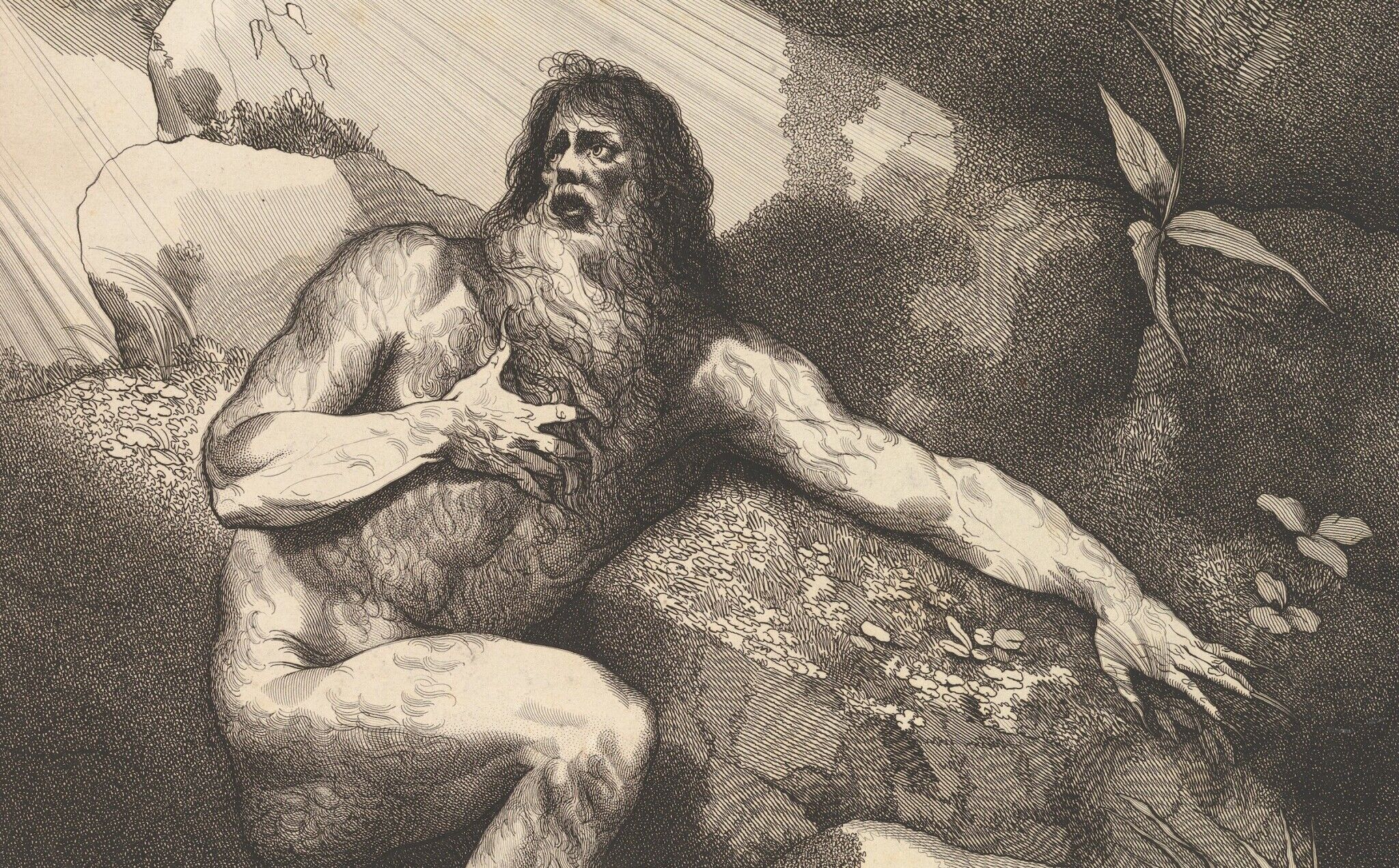

The Bible also records, however, that Nebuchadnezzar lost his mind for a time. Daniel wrote that the king was driven from the kingdom and behaved as an animal so that he might know that “the Most High ruleth in the kingdom of men” (Daniel 4:23).

It’s a powerful story, but is there any evidence?

Archaeology of a Proud King

Nebuchadnezzar ii was an amazing builder, an achievement he boasted about in both the biblical text and in inscriptions that have been discovered through archaeological excavations. The most prominent of these discoveries are the bricks of hundreds of ancient ruins bearing stamped inscriptions about Nebuchadnezzar’s works.

Sir Henry Rawlinson, sometimes called “the Father of Assyriology,” wrote: “With regard to Babylonia proper, it is a remarkable fact that every ruin from some distance north of Baghdad, as far south as the Birs Nimrud, is of the age of Nebuchadnezzar. I have examined the bricks in situ, belonging to perhaps 100 different towns and cities within this area … and I never found any other legend than that of Nebuchadnezzar (ii), son of Nabopalasar, king of Babylon” (A Commentary on the Cuneiform Inscriptions of Babylonia and Assyria).

Babylon itself was built by Nebuchadnezzar. “As far as the town of Babylon is concerned, I admit without hesitation, that it owed its origin to that king (Nebuchadnezzar ii), for the name is never once mentioned in the inscriptions anterior to the time of Nebuchadnezzar,” Rawlinson wrote. Numerous inscriptions attest to this grand constructive work. His southern palace is the most completely excavated large building from ancient Babylon; it boasts over 50 courtyards and more than 600 rooms (“Neo-Assyrian Texts From Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon,” by Olaf Pedersen).

The Bible accurately reflects Nebuchadnezzar’s self-aggrandizing as a master builder. Daniel 4:27 quotes Nebuchadnezzar, saying, “‘Is not this great Babylon, which I have built for a royal dwelling-place, by the might of my power and for the glory of my majesty?’” According to Daniel, this was Nebuchadnezzar’s final boast before being struck with madness.

The Chronology of Lunacy

Some scholars have claimed there is no chronological gap in Nebuchadnezzar’s reign viable for his period of madness. “Enough is known of Nebuchadnezzar’s 43-year reign so that it is impossible to fit in such a period of insanity,” wrote theologians Alexander Hartman and Louis Di Lella (Anchor Bible, 1978). Can we be so dogmatic? Let’s first consider the duration of Nebuchadnezzar’s madness.

“And thou shalt be driven from men, and thy dwelling shall be with the beasts of the field; thou shalt be made to eat grass as oxen, and seven times shall pass over thee; until thou know that the Most High ruleth in the kingdom of men, and giveth it to whomsoever He will’” (Daniel 4:29). Nebuchadnezzar suffered this lunacy for “seven times.” There is a lot of debate over how long this may be. Strong’s Concordance equates a time to a year (e.g. Daniel 7:25). In Aramaic, it is believed that “times,” when referring to a tree as Daniel 4 (verses 10-16), refers to the times that buds would appear on the tree: once a year. This means that Nebuchadnezzar’s madness lasted for 7 years.

Are there seven years in the secular history of Nebuchadnezzar that could match the story of Daniel 4?

Nebuchadnezzar ascended to the throne in 605 b.c.e. The next 10 years of his life are described in both the Bible and Babylonian texts. He emerges in the biblical text in 597 and 586 b.c.e. and is known to have had exploits in the intervening periods. Shortly after Jerusalem’s fall in 586 b.c.e., Nebuchadnezzar began what was called the siege of Tyre, which lasted until 573 b.c.e. Ezekiel wrote that at the end of this siege Nebuchadnezzar himself defeated Tyre (Ezekiel 26). Josephus also writes about a conquest by Nebuchadnezzar against Lebanon, Moab and Ammon in 582 b.c.e.

Between 582 and 573 b.c.e., there is a gap in both biblical and Babylonian chronology. He may have descended into insanity shortly after his Lebanon-Ammon-Moab campaign while the siege of Tyre ensued. Seven years later, he would have regained his mental acuity and finished the job he started at Tyre.

Hebrew Bible scholar Jeffrey M. Niles wrote that after seven years, Nebuchadnezzar still would have had “several weeks or months to shave, trim his nails, apologize to his wife for his beastly behavior, and to present himself at Tyre in time for its surrender sometime during his 32 regnal year. … Therefore, there is a gap in the record of Nebuchadnezzar’s reign in which the Babylonian king remained notably unaccounted for” (“Mowing Lawns in Babylon: Madness of Nebuchadnezzar and Divine Sovereignty”).

The gap of time between 572 b.c.e. and 562 b.c.e. is also conspicuously silent. After the siege of Tyre, no Babylonian documents provide details about Nebuchadnezzar’s life until his death in 562 b.c.e. It’s possible Nebuchadnezzar descended into madness during this gap. Some documents do indicate that the government continued to function during this period, but they could have easily done so under a regent or interim official. It is simply inaccurate for historians to claim there is no 7-year period in which Nebuchadnezzar was unaccounted for.

The Babylonian Record

The book of Daniel continues the story with quotations from Nebuchadnezzar himself. “‘And at the end of the days I Nebuchadnezzar lifted up mine eyes unto heaven, and mine understanding returned unto me, and I blessed the Most High, and I praised and honoured Him that liveth for ever’” (Daniel 4:31).

Does Nebuchadnezzar record this episode anywhere else? Nebuchadnezzar would not have had any self-serving motivations to proclaim his own insanity. Aside from the Bible, most ancient writings are shameless propaganda designed to boost the standing of the king and glorify his actions. The Bible is unique for describing the faults of its heroes.

Hebrew Bible scholar and archaeologist Siegfried Horn wrote: “It should not surprise us, then, if we find no corroboration of Nebuchadnezzar’s mental illness in Babylonian records. And, when we consider the humiliating nature of the affliction, the likelihood of the royal archives preserving documentation of the event seems most unlikely” (New Light on Nebuchadnezzar’s Madness, 1978). Yet despite this, there are a few records worth careful examination.

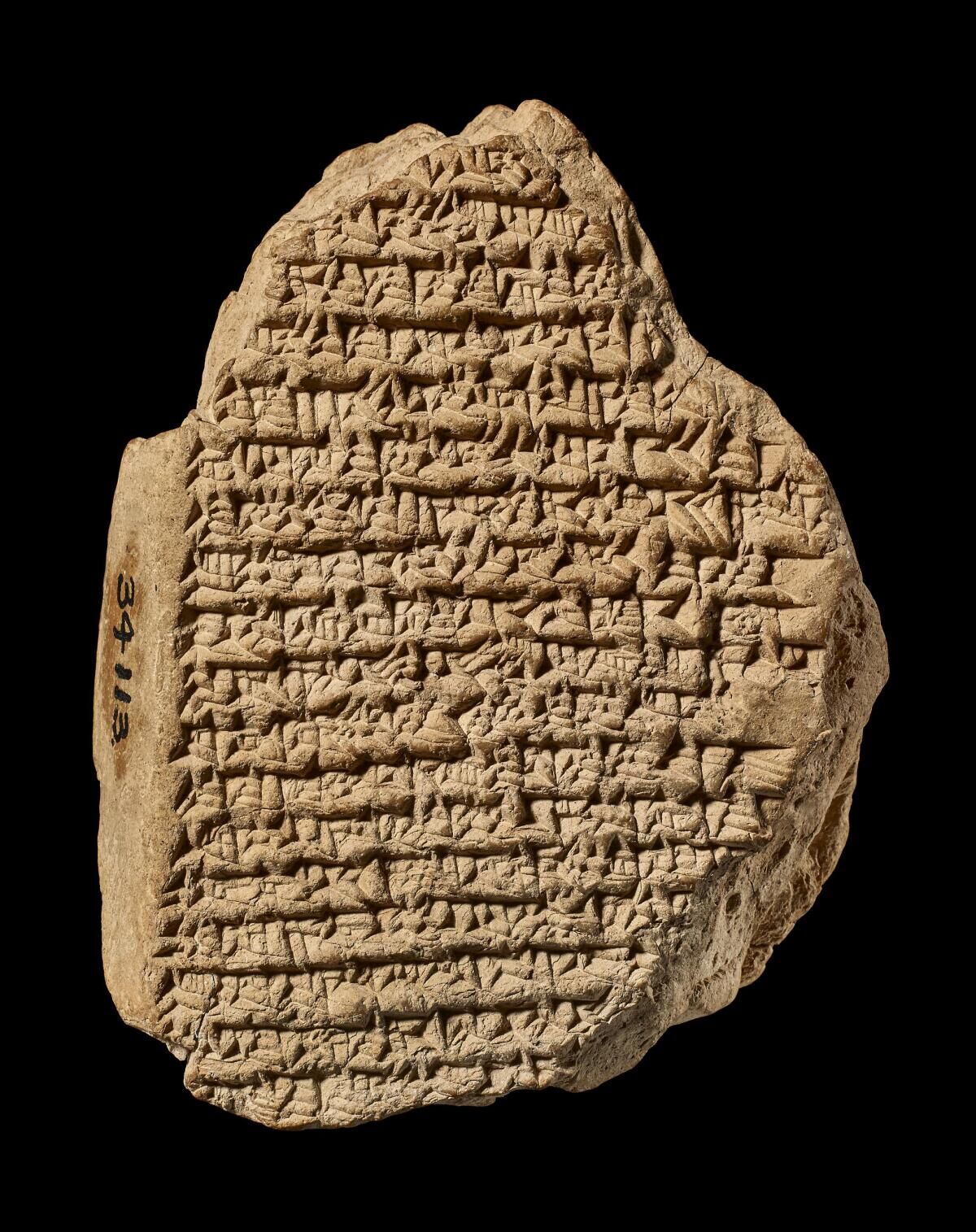

One such example is a Babylonian tablet (BM34113) that was discovered in Iraq in the 1880s by Hormuzd Rassam. It was translated and published by University of Toronto professor Albert Kirk Grayson in 1975. It is only fragmentary, but the fragments contain interesting clues that Nebuchadnezzar had a period of mental problems. The following translation is only about one sixth of what was originally on the tablet:

1) […]

2) [Nebu]chadnezzar considered

3) His life appeared of no value to [him, …]

4) [H]e stood and [took] the good road to […]

5) And (the) Babylon(ian) speaks bad counsel to Evil-merodach […]

6) Then he gives an entirely different order but […]

7) He does not heed the word from his lips, the cour[tier(s) - - -]

8) He changed but did not block […]

9) Concerning the treasure of Esagil and Babylon and securing [their foundations … ]

10) The cult-centres of the great gods they/he considered … […]

11) He does not show love to son and daughter […]

12) … family and clan do not exist […]

13) In his heart, towards everything that was abundant […]

14) His attention was not directed towards promoting the welfare of Esagil [and Babylon]

15) With his ears alert he went into the Holy Gate […]

16) He prays to the lord of lords, he raised [his hands (in supplication) (…)]

17) He weeps bitterly to Marduk, the g[reat] gods […]

18) His prayers go forth to […]

Evil-merodach was the son of Nebuchadnezzar, as indicated in 2 Kings 25 and Jeremiah 52. He was the heir apparent of Babylon and would have probably served as his father’s regent during his illness.

In “New Light on Nebuchadnezzar’s Madness,” Siegfried Horn does a brilliant job explaining this tablet in the light of Daniel 4:

Read lines 3, 6, 7, 11, 12, and Mas referring to strange behavior by Nebuchadnezzar, which has been brought to the attention of Evil-merodach by state officials. Life had lost all value to Nebuchadnezzar, who gave contradictory orders, refused to accept the counsel of his courtiers, showed love neither to son nor daughter, neglected his family, and no longer performed his duties as head of state with regard to the Babylonian state religion and its principal temple. Line 5, then, can refer to officials who, bewildered by the king’s behavior, counseled Evil-merodach to assume responsibility for affairs of state so long as his father was unable to carry out his duties. Lines 6 and on would then be a description of Nebuchadnezzar’s behavior as described to Evil-merodach. Since Nebuchadnezzar later recovered (Daniel 4:36), the counsel of the king’s courtiers to Evil-merodach may later have been considered “bad” (line 5), though at the time it seemed the best way out of a national crisis.

This tablet describes an episode that reflects no other event we know of in Nebuchadnezzar’s life except the madness of Daniel 4. Clearly, Nebuchadnezzar was having some serious mental issues. “If our interpretation of this new cuneiform text is correct,” Andrews University professor Gerhard Hasel wrote, “we have for the first time extrabiblical contemporary historical evidence that corroborates and supports the account in Daniel 4” (“The Book of Daniel: Evidences Relating to Persons and Chronology,” 1981).

Is this interpretation of the tablet completely certain? No. Should it be considered before scholars utterly reject the historicity of Nebuchadnezzar’s madness? Absolutely.

‘The Prayer of Nabonidus’

Nabonidus was the last true king of Babylon before the city fell to Cyrus the Great in 539 b.c.e. He was not a descendent of Nebuchadnezzar. Rather, he usurped the throne from Nebuchadnezzar’s grandson Labashi-marduk. He was the father of Belshazzar, the ruler of Babylon in Daniel 5.

Numerous papyrus scrolls were found in the site of Qumran dating from the second century b.c.e. One cave yielded four interesting scraps of paper now called 4Q242 or “The Prayer of Nabonidus.” Though attributed to a different king, the similarities between this text and Daniel 4 are striking.

A section of the text (translation from Fragments of the Prayer of Nabonidus, by Harvard professor Frank Moore Cross) from 4Q242 reads:

1) The words of the p[ra]yer which Nabonidus, king of [Ba]bylon, the great king, pray[ed when he was stricken]

2) with an evil disease by the decree of G[o]d in Teman. [I Nabonidus} was stricken with [an evil disease]

3) for seven years, and from [that] (time) I was like [unto a beast and I prayed to the Most High]

4) and, as for my sin, he forgave it. A diviner—who was a Jew o[f the Exiles—came to me and said:]

5) ‘Recount and record (these things) in order to give honor and great[ness] to the name of the G[od Most High.’ And thus I wrote: I]

6) was stricken with an evil disease in Teman [by the decree of the Most High God, and, as for me,]

7) seven years I was praying [to] gods of silver and gold, [bronze, iron,]

8) wood, stone (and) clay, because [I was of the opini]on that th[ey] were gods[…]

While fragmentary, this passage is still striking: A king of Babylon is afflicted with a 7-year illness cast on him by a deity and is treated by a Jewish exile—these details all match Daniel 4.

The biggest issue is that the text is clearly attributed to Nabonidus rather than Nebuchadnezzar. The names Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus were more similar in Aramaic than they sound today in English. They come from the same root word (the theophoric “Nabu”—a Babylonian deity). Interestingly, Herodotus, a Greek historian who traveled to Babylon 90 years after Nebuchadnezzar’s reign, called Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus by the same name: Labinetus. An Aramaic scribe from Qumran 300 years after Nabonidus could have easily confused these kings.

Even if this text is rightfully attributed to Nabonidus, the Bible indicates that Daniel was still a renowned theologian in the time of Nabonidus (Daniel 5:11), so this Jew from the exile was still most likely the Prophet Daniel. Several other Babylonian documents indicate that Nabonidus did suffer an illness. Regardless, this papyrus is a striking corroboration of biblical history since it postdates the writing of Daniel.

Biblical Conclusions

Nebuchadnezzar died in 562 b.c.e. He fought battles with Egypt, conquered Judah, destroyed Jerusalem, and constructed some amazing structures—all details described in the Bible and confirmed by archaeology. The Bible says that the Prophet Daniel was a high-ranking official serving in Nebuchadnezzar’s court. Daniel more than almost anyone would have known the victories and the maladies of this world-ruling king.

Modern scholarship cannot claim that the account of Nebuchadnezzar’s madness in Daniel 4 is fabricated or entirely ahistorical. In fact, there are several striking historical texts that provide corroboration that Nebuchadnezzar ii really did go mad.