Of all the ancient cities in Israel, Jerusalem is the most topographically unique. Most ancient cities—like Megiddo, Lachish and Gath—are built on a single high hill. This makes the entire tel more easily defensible. Jerusalem, however, is built on a long, narrow ridge that rises in elevation from the south to the north.

The Gihon Spring, Jerusalem’s only perennial water source, is situated deep in the valley on the southeastern part of the ridge. Both archaeology and the biblical text reveal that early Jerusalem (from the Bronze Age into Iron i) was situated beside this spring, which means the city was built on the lower southern portion of the ridge.

The situation of the early city has long created a quandary for archaeologists attempting to reconstruct the history of Jerusalem. Strategically, the city would have been vulnerable to attack from the north, where the elevation was higher. This even led a few scholars to posit that the ancient core of Jerusalem wasn’t centered around the spring but on one of the higher peaks on the northern part of the ridge. For those who believed that the city was situated farther south, as the archaeology and biblical account suggest, the question remained: Where exactly was the northern border of the original city?

Now, thanks to one monumental discovery, the calculus on Jerusalem’s ancient topography has changed. This discovery not only answers the question about the northern limits of the ancient city, but also settles the question about the original location of Jerusalem.

A Surprising New Discovery

The Givati Parking Lot excavation is currently the longest-running excavation in Israel (the massive dig began in 2007). When I first visited the site in 2006, it was still a parking lot. Today it’s an impressively deep excavation site, with preserved remains from the Iron Age all the way to the Ottoman period. The site is located on the northwestern slope of the Eastern Hill, the area of Jerusalem’s most ancient settlement.

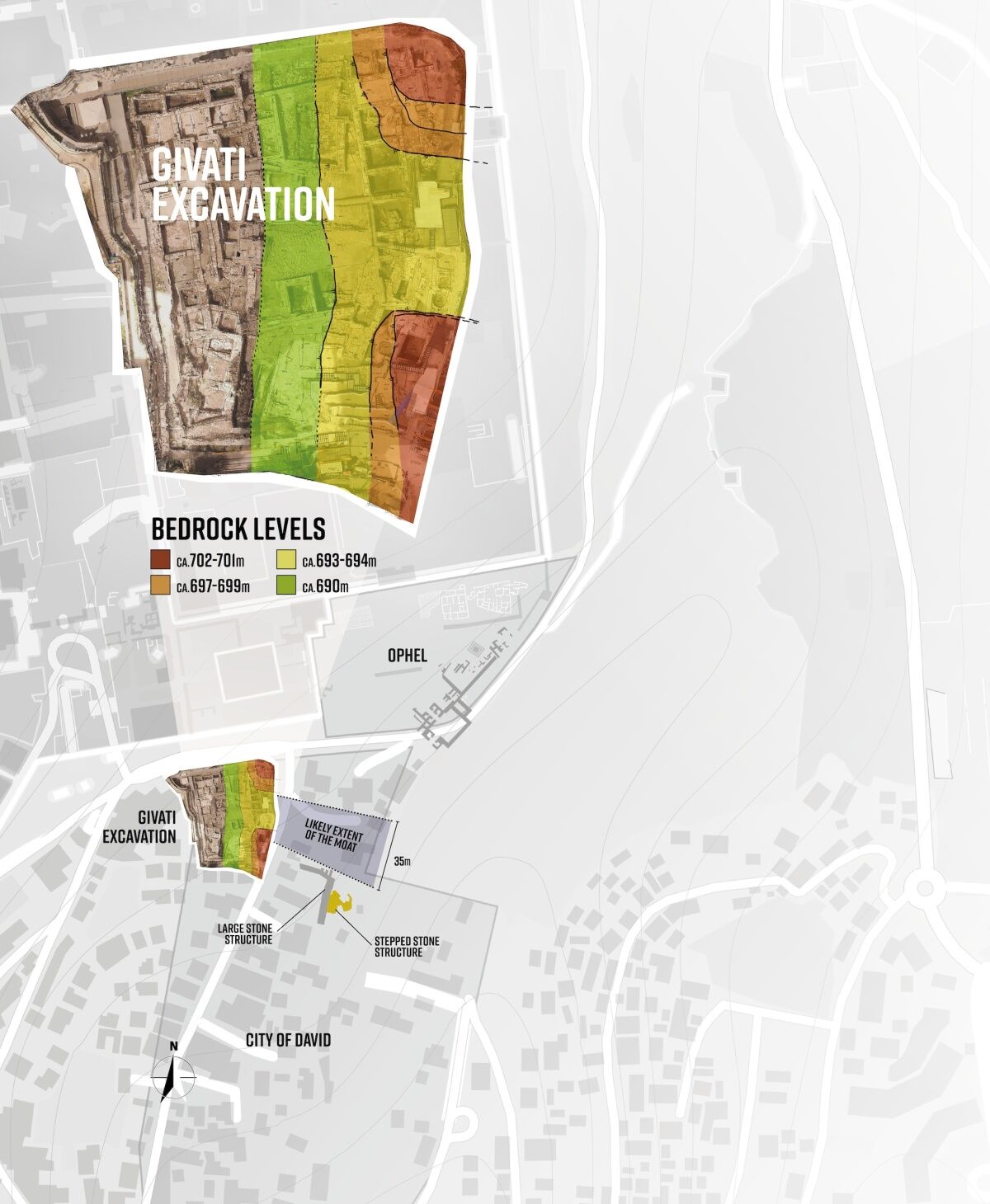

In the last few years, the excavation team from Tel Aviv University and the Israel Antiquities Authority have unearthed a man-made gorge in the bedrock. At 35 meters (115 feet) wide and 6 to 9 meters (20 to 30 feet) high, the cut section is massive. (A full description of the moat was published in the Tel Aviv University Journal in an article titled “An Early Iron Age Moat in Jerusalem Between the Ophel and the Southeastern Ridge/City of David.”)

Archaeologists have excavated the western slope of the ridge and have exposed a large cross section of the moat. While a road and residences prevent further excavation east, previous small-scale excavations conducted near the center of the ridge by Kathleen Kenyon in the 1960s and Rina Avner in 2003 revealed lower-than-expected bedrock heights. The Givati team, by combining their findings with those of Kenyon and Avner, concluded that the moat almost certainly continues across the entire width of the ridge. The excavators also believe the moat was man-made, and not a natural feature.

This is a major discovery: It means that the original City of David was at one time separated from the Ophel and Mount Moriah by a gigantic trench.

When was the moat built?

We don’t know exactly, and it is almost impossible to determine (at least for now). We can, however, identify the latest possible time that the moat was built.

The southern bedrock wall of the moat is extremely steep (it’s the deepest part of the entire feature). The gradient of the wall is so steep archaeologists believe it had to be carved (formations like this are not known to occur naturally in the Meleke rock formations in Jerusalem).

The northern slope of the moat isn’t nearly as steep. It also descends in two steps. As part of the step-down, excavators uncovered curious bedrock grooves running north-south in the same direction as the moat.

Archaeologists excavated inside three grooves and observed a thin whitish surface made of crushed limestone. Under this surface they found a stratified fill with pottery types indicative of the early Iron iia period (10th century b.c.e.) through to perhaps the Iron iia-b transition, or the late ninth century. After studying this and other stratigraphic data, the excavators concluded: “It may be safely determined that the cutting of the ditch occurred no later than the late Iron iia.” According to them, this would be the late ninth century—about 100 years after the death of King Solomon.

Note, this is the latest possible date of construction. It is probable, as the Givati team believes, that the moat was constructed long before the late ninth century b.c.e.

When was the moat filled and lost to history?

This is an easier question to answer, thanks to the mass of material found dating to the late Hellenistic Period (early second century b.c.e.) that continues all the way to the bottom of the moat. On the west side, there is also a large north-south wall built on the bottom of the moat. Previous excavators of the site dated this wall to the early second century b.c.e., around the time of Antiochus Epiphanes. However, the current excavators believe that the wall was in use during the Persian Period and must have been built earlier.

What is the purpose of this large trench that appears to have separated southern and northern Jerusalem for over 600 years?

Archaeologists can only offer educated guesses. Initially, when the city was confined to the southern part of the ridge, the moat acted as an essential defensive line. As the land lay naturally, there was nothing to stop an enemy army attacking the city from an elevated position to the north. But the bold addition of a 35-meter-wide moat with steep walls interrupted the gradual slope, giving the northern part of the city a much stronger defense.

When the city of Jerusalem expanded north, the authors suggest, the moat provided a buffer between the city’s elite occupying the Ophel area and the lowly city dwellers to the south. The division of a city along socioeconomic lines has a parallel in other cities, such as Hazor. It was once argued that this style of division was evidence of the Israelite King Omri’s handiwork. However, the authors discount the moat as an Omride feature because it likely predates his rule.

With commendable humility, the authors don’t pretend to have all the answers. They admit, for example, that we don’t know how the moat was bridged. Was there a bridge made of wood? Were there stairs going down and up? One of the authors, Dr. Yiftah Shalev, put it best in an interview with Haaretz: “The elephant is in the room. I cannot explain how everything worked, but I cannot ignore this structure, which clearly existed.”

Monumental Change in Jerusalem

Given the difficulty in precisely dating the construction of the trench, the Givati team prefers not to associate the moat with a historical or biblical personality. They do, however, associate the moat with the monumental change that occurred in Jerusalem in the Iron iia period, the period generally associated with kings David and Solomon. So while the archaeologists refrain from explicitly mentioning the united monarchy, the elephant in the room is that the moat could be the handiwork of David or Solomon.

How is the moat connected to the monumental change in architecture that occurred in Iron iia?

It needs to be considered alongside the archaeological discoveries from this same period in the areas directly northeast and southeast of the ditch, both of which were excavated by the late Dr. Eilat Mazar of Hebrew University.

First, as the Givati report notes, there’s the “monumental complex” discovered on the Ophel over the past 15 years, which includes what Dr. Mazar believed to be a 10th-century city wall. Although they take the view that some of the large buildings on the Ophel can possibly be dated a little later than Iron iia, they note the early Iron iia dating of the “massive constructional fill” that supported a large Ophel structure.

Second, there are the Iron iia remains discovered immediately southeast of the trench, in the northernmost part of the City of David. The most important feature in this area is the Stepped Stone Structure, situated about 15 meters (50 feet) south of the proposed eastern side of the moat. Measuring over 20 meters (66 feet) tall, the Stepped Stone Structure is by far the largest man-made feature from the Iron Age ever discovered in Israel.

We know too, thanks to the work of Eilat Mazar, that the Stepped Stone Structure functioned as a retaining wall for a monumental building on top of the ridge. That upper building, technically known as the Large Stone Structure but designated by Dr. Mazar as King David’s palace, dated to the time period of King David’s building program in Jerusalem (2 Samuel 5).

While the Givati team avoided the debate over the Large Stone Structure, it clearly accepted Dr. Mazar’s dating of the structure: “We share the commonly accepted view that it was constructed during the very late Iron i or the early Iron iia and continued to function in its original form into the late Iron iia or early Iron iib …. [T]he remains … provide evidence for the presence of a public building south of the barrier through the Iron iia.” In short, it was constructed around the time of King David.

The construction of the monumental moat needs to be considered alongside the construction of these two monumental structures, the Stepped Stone Structure and Large Stone Structure. Were these three epic features built at the same time and by the same ambitious builder? Or were they built over the course of the expansion of the city over two or three generations? It’s difficult to know for certain, at least for now. Nevertheless, as the Givati report states, “The Iron iia was a time of major building activities, which went hand in hand with massive landscaping projects.”

Then, in a statement reminiscent of the late Dr. Mazar, they write: “All of these projects may not have taken place simultaneously, but they are part of the same royal mindset that dramatically changed the urban landscape of Jerusalem and can be placed, generally speaking, in the formative movements of Iron Age Jerusalem—i.e. the end of the Iron i until the beginning of the Iron iib.”

This is a noteworthy and admirable admission from the team at Tel Aviv University and the Israel Antiquities Authority, archaeologists who do not typically support the notion of an early monarchy construction in Jerusalem. Granted, if we paired their archaeological dating with the biblical kings, the window of time discussed by the archaeologists includes a handful of monarchs after David and Solomon. Nevertheless, kudos to the team for boldly connecting their moat discovery with the other monumental discoveries of Iron iia Jerusalem.

Possible Historical Reconstructions

With no construction date and only a portion of the moat revealed, the Givati team refrained from integrating the scarp into a broader chrono-historical reconstruction. And they didn’t make any connections to the biblical text. Does the Bible say anything about a moat in Jerusalem? And can we, using the biblical text and archaeology, develop a plausible model?

Perhaps. First, the discovery of the moat fits extremely well with the progression of Jerusalem’s expansion from south to north as discussed in the Bible during the same time period.

The Bible—paired with geography, history and archaeology—describes the expansion of the city from the end of Iron i through to the end of Iron iia. This period covers the city’s transition from Jebusite to Israelite rule, through the dissolution of the united monarchy, and stops sometime in the ninth century, depending on which archaeologist you speak to. Thus, we are working with about 150 years of history.

2 Samuel 5 is a key chapter describing the history and expansion of Jerusalem at this time. Immediately following David’s coronation over the northern tribes of Israel and the creation of the united monarchy, David’s men took Jerusalem from the Jebusites. Israel’s soldiers penetrated the city probably through some type of water shaft or gutter, indicating that the spring was accessible within the walls of the Jebusite city. Furthermore, a much earlier Middle Bronze Age fortification around the spring and associated water tunnel system shows that the earliest city had a border as far north as the line of the Gihon Spring. We know too that, at least initially, David dwelt in the fortress city of Zion (the city of the Jebusites), which he renamed the City of David (verses 6-9).

After taking Jerusalem, David went to work developing the land adjacent north of the city. “And David dwelt in the stronghold, and called it the city of David. And David built round about from Millo and inward” (verse 9). This verse implies that David lived inside the former Jebusite city while he was expanding the city in the only direction possible—north, up the ridge.

Note the word “Millo” in verse 9. There are many theories about the “Millo,” what it was and where it was located. The word has the connotation of a filling. Regarding its situation, the most recent theory posits that it was a tower surrounding the Gihon Spring deep in Kidron Valley. Alternatively, it would be tempting to look at this new moat as perhaps related to the Millo. Certainly, at some point, the moat was filled. But considering the moat appears to have remained unfilled through the period of Israelite rule in Jerusalem, it is unlikely to be associated with the Millo.

Many archaeologists believe the Millo refers to the Stepped Stone Structure. Both the Stepped Stone Structure and the Large Stone Structure date to the period in which David began to reign in Jerusalem (the transition from Iron i to Iron iia). Furthermore, while the Stepped Stone Structure is often understood to be a retaining wall, it could be more accurately described as a massive fill of uncut boulders shoring up a huge void in the bedrock along the eastern edge of the ridge. These massive boulders are hidden from view, behind the outer stepped facade of the structure, making it easy to overlook the “fill” nature of the Stepped Stone Structure.

In 2008, as a supervisor under Dr. Mazar on her City of David dig, I entered a tunnel that ran behind the Stepped Stone Structure. In some sections, the distance between the bedrock cliff and the facade of the Stepped Stone Structure was roughly 15 meters (50 feet), indicating the monumental nature of the rock fill. The fill area is certainly large enough to be given the landmark title “Millo.” Perhaps the fill used behind the Stepped Stone Structure was the rock quarried to create the moat.

When David finished the Millo, he constructed his palace with the help of the king of Tyre. As Dr. Mazar noted, after studying 2 Samuel 5:17, the palace was built on higher ground than the original Jebusite fortress:

“[A]ll the Philistines went up to seek David; and David heard of it, and went down to the hold [fortress].”

Given that both the Stepped Stone Structure and the Large Stone Structure date to the period when David conquered Jerusalem, it’s logical to conclude that David’s palace is the Large Stone Structure. As Mazar’s excavations proved, the Large Stone Structure was built on an open area (no earlier structures were found on the site, although there was an accumulation of earth on the bedrock, up until the Iron i period).

Perhaps the moat was constructed after the Philistine invasion, with David realizing the need for a more defensive position.

According to the biblical text, King Solomon was responsible for expanding Jerusalem northward on the ridge. If the moat already existed, certainly, an expansion into the wider Ophel Hill would once again create a situation where the new northern border of the city would be under threat. Such an elaborate expansion of the city onto the other side of the moat would at least temporarily leave the new part of the city vulnerable to attack.

However, as the biblical text relates, the Solomonic era was one of peace and tranquility, which would have allowed for construction outside of the city’s previous defenses. It was during the first 20 years of that peace that King Solomon created a new royal acropolis on the Ophel, which included his new palace, new armory, the temple and a new city wall that connected the new “City of Solomon” to the City of David, at which point the moat would have lost its original function as a defensive fortification (1 Kings 3:1).

This biblical description of Jerusalem’s Iron i to Iron iia expansion matches remarkably well with the archaeological data presented in the recent Givati Parking Lot report. Naturally, more archaeological excavation is needed to confirm or deny such a reconstruction.

But for now, congratulations to the Givati team not only for their incredible work discovering the moat, but for their fair and accurate analysis and reporting of the excavation data. With the discovery of the moat at the northern reaches of the City of David, a new dimension of Jerusalem’s epic history during the age of the early biblical kings of Judah has been revealed!