Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Philistines

The word “Philistine” is a rather degrading term in the English language—search a thesaurus, and you’ll find parallel terms like “ignoramus,” “primitive,” “uncultured,” “tasteless.” The ancient Philistines, oftentimes archenemy to the Israelites, were certainly a violent people. Yet as archaeological discoveries have now revealed, the Philistines were, in fact, a cultured nation with extremely skilled craftsmen. While knowledge of the Philistines through archaeology is still comparatively sparse, let’s look at what has been unearthed thus far and compare it with the biblical record.

Origins

The Bible indicates an Aegean origin for the Philistines—describing them as coming from the “country [island] of Caphtor,” which was possibly Crete, Cyprus, or some other Mediterranean area (Amos 9:7; Jeremiah 47:4; Deuteronomy 2:23). Archaeology has provided evidence for the Aegean origins of the Philistines—there are unmistakable similarities between Philistine and Aegean pottery, burial practices, diet, gods, weaving weights and cooking hearths. Interestingly, the name Philistine has been proposed as a form of the Greek term phyle histia—meaning “tribe of the hearth.” The ancient Israelites are known to have used ovens for cooking, while the Philistines instead preferred their unique, Aegean-style hearths.

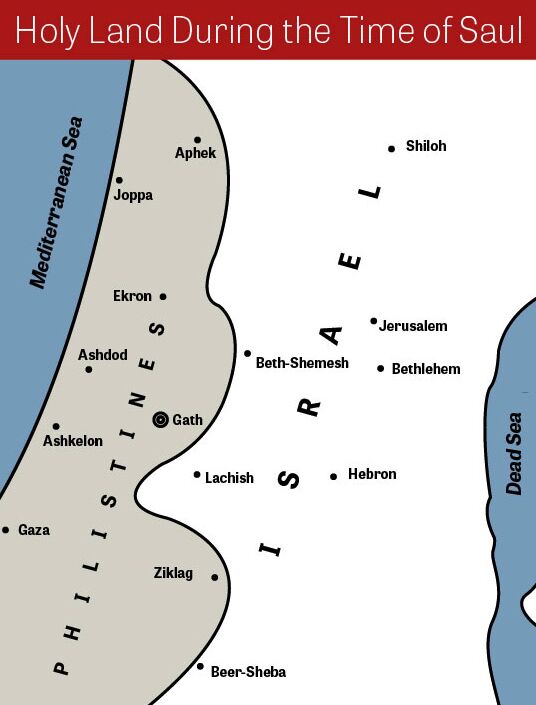

The Bible’s first mention of their presence in the Holy Land dates back to the 19th century b.c.e., during the time of Abraham. The earliest archaeological records of the Philistines (pronounced Plishteem in Hebrew) are found in Egyptian inscriptions. These records list the Peleset peoples as having come from the sea and attacked the Egyptian mainland around the 12th century b.c.e., before being beaten back and settling into the eastern coast of the Levant, alongside Israel. This was likely one of several Philistine migratory “waves” to the Middle East—during the earlier time of Abraham, certain of their ancestors would have already established a smaller Philistine nation-state along the edges of the Holy Land.

Early History

The first biblical mention of the Philistines is in Genesis 20 and 21. Abraham had been living in the land of the Philistines, and his wife, Sarah, was taken in by the Philistine King Abimelech to be his wife. Abimelech was not aware that Sarah was already a married woman—a fact that God revealed to the Philistine king in a dream. Sarah was subsequently released, and Abimelech granted Abraham a great many gifts and approval to live wherever he pleased within the Philistine land. “God is with thee in all that thou doest,” he later told Abraham (Genesis 21:22). Abraham then covenanted that he would not deal falsely with Abimelech or his descendants. Thus began, quite unusually, peaceful and very positive relations between the early Philistines and the Israelite forefathers. Isaac himself knew the Philistine king of his day (Genesis 26), and lived within the land during a famine. Over time, however, Isaac began to grow significantly in power and wealth, worrying the Philistines. The king subsequently requested that Isaac leave their land. Isaac obliged.

By the time of the Exodus, the Philistines were known for their savage, warlike nature. In fact, the reason the Israelites crossed into the Promised Land by taking the long way around was because of the Philistines: God specifically wanted Israel to avoid contact with the fierce nation (Exodus 13:17) and thus prevent any desire for the Israelites to return to Egypt. (Of course, the rebellious Israelites still found a plethora of excuses to return anyway.) By the time the Israelites had entered Canaan and their leader Joshua was nearing death, God instructed him that the Philistine land still had yet to be conquered (Joshua 13:1-3).

Based on archaeological depictions, the Philistine soldiers were tall, clean-shaven men who wielded straight swords and spears, and wore breastplates and short kilts. The first serious battle recorded between the Philistines and Israel is mentioned briefly in Judges 3:31. Some time around Israel’s captivity to the Moabites, the Philistines had evidently oppressed the Israelites in some shape or form. “And after him was Shamgar the son of Anath, who smote of the Philistines six hundred men with an ox-goad; and he also saved Israel.”

Samson and the Philistines

One of the better-known stories of the Philistines is in relation to Samson. These events occurred around the 12th century b.c.e.—about the same time that Egypt was facing the invasion by the sea peoples (including the Philistines). During this period, the Philistines conquered the Israelite city Gezer and established themselves as powerful oppressors over the wider Israelite population. “And the children of Israel again did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord; and the Lord delivered them into the hand of the Philistines forty years” (Judges 13:1). To release Israel from that oppression, God raised up from the tribe of Dan the incredibly strong Samson.

There are a couple of interesting archaeological points that can be made of the Samson account. Judges 14 records that he wrestled and killed a lion with his bare hands on his way to the Philistine city of Timnath. Not far away from where this incident would have happened, in the city of Beth-Shemesh, a small stone seal dating to Samson’s time period was found, depicting a man with a lion. The imagery, location and dating of the find have led to speculation that it is a link to Samson’s killing of the lion.

Toward the end of his life, Samson was enticed by Delilah, had his hair cut, and he lost his God-given strength. As a result, he was captured, had his eyes put out, and he became a Philistine slave and showpiece. During celebrations of his capture in a temple of the god Dagon, Samson was led by a young boy between two central support pillars of the temple. After praying for strength, he forced the pillars apart, causing the temple to crash down, killing the reveling Philistines.

The construction feature of two central supportive pillars has remarkably been found in archaeology. A temple with two central pillars was discovered at the Philistine city of Gath (identified as the modern site Tel es-Safi). The same was found at Tel Qasile (a Philistine port city). This must have been a known design element for Philistine temples. And both sets of pillars would have been close enough for a tall man to spread himself between.

Samson personally killed thousands of Philistines over the course of many various struggles. One theory is that Samson was the inspiration for the legendary Greek strongman Hercules (both killed a lion with their bare hands, both met their demise with a lover, etc.). Could the Greek legend have been passed down through the Philistines’ Greek/Aegean descendants, or perhaps through Samson’s seafaring Danite tribe? (Judges 5:17).

Our next mention of the Philistines in biblical history is during the time of a young Samuel. The Philistines fielded a large army against the Israelites, and slaughtered about 34,000 of them in a stunning victory (1 Samuel 4:3, 10). What was even more stunning was that they captured the ark of the covenant, bringing it back to Philistine territory as a war trophy. However, this led to a world of trouble for the Philistines. Placing it before their god Dagon resulted in the idol being found prostrated before the ark the next morning. Setting Dagon back upright, the priests found him on the ground smashed in pieces the following morning. Furthermore, a deadly plague struck throughout the Philistine land wherever the ark was transported. Finally, the ark was returned to the Israelites. The Philistines tried soon after to conquer the Israelites again, but their army was wiped out during a ferocious thunderstorm (1 Samuel 7:10). Several battles later ensued under the reign of King Saul.

David and Goliath

This is undoubtedly the most famous account of the Philistines: the battle between the small, young underdog, David, and the towering giant, Goliath. The Philistines had gathered themselves against the Israelite army at the Valley of Elah. Their champion, Goliath, would periodically emerge from the ranks of Philistine men in order to denigrate the Israelite forces and challenge an Israelite soldier to one-on-one combat in order to determine which nation would become subservient to the other. (Interestingly, this method of deciding a battle continued through Greek history, as described by the Iliad.) The faithful David killed the giant with a sling, then cut off his head. The Israelites chased down and slaughtered the fleeing Philistine army.

Even here, archaeology has much to add to this account. A fortress where the Israelite forces most likely were based for this battle has been found. And while no remains of the giant have yet been found, something can be said at least for his name. Goliath was from Gath. Two inscribed names have been found on pottery at the site (dating to the 10th century b.c.e.), bearing a similar linguistic link to Goliath—Alwat and Wlt. Of course, our Anglicized version of “Goliath” is much different from the original rendering—pronounced in Hebrew as Galyat. These names all show Indo-European roots rather than Semitic roots like the Canaanite and Hebrew names. This further confirms the distant Mediterranean origins of the Philistine peoples.

Goliath’s hometown Gath was certainly able to accommodate people of large stature. In excavations during the summer of 2016, a massive city wall and huge entry gate were discovered at the city. According to the site’s director, the gate is one of the largest ever found in Israel. David himself would have been familiar with the gates of Gath—while on the run from Saul, he sought refuge “incognito” in the Philistine city. Upon realizing the Philistines suspected who he was, David, fearing for his life, feigned madness, drooling and scratching marks into the city gate (perhaps this was the very gate found at Tel es-Safi!). David ended up escaping with his life. Thus far, only the top section of this city wall and gate at Gath/Tel es-Safi has been exposed.

Gath is also listed in 2 Samuel 21:15-22 as the home to four other giants, all of whom were conquered by the Israelites during the time of David.

Continuing History

Multiple wars continued between the Israelites and the Philistines, yet relations weren’t always terrible. In fact, while David was still on the run from Saul, the ruler of Gath gave him and his men the territory of Ziklag as their own (1 Samuel 27:6). Ownership of this land would continue under the subsequent kings of Judah. Still, numerous battles against the Philistines ensued throughout the reign of David.

During the reign of the righteous Judean King Jehoshaphat, the Philistines brought presents and tribute (2 Chronicles 17:11). Yet under his evil son Jehoram, the tables turned and the Philistines (among other nations) made inroads into Judah, reaching as far as the “king’s house” and taking captive his wives and sons (2 Chronicles 21).

Excavations at Tel es-Safi have revealed evidence that during this late ninth century b.c.e., after the death of Jehoram, King Hazael of Syria came and destroyed Gath in a massive siege—the earliest known siege-system in the world. A large trench had been dug around the city, 2.5 kilometers long, 8 meters wide and 5 meters deep. This powerful attack of Gath is recorded in 2 Kings 12:18: “Then Hazael king of Aram went up, and fought against Gath, and took it; and Hazael set his face to go up to Jerusalem.”

Judahite King Uzziah’s eighth-century b.c.e. reign once more saw Israelite victory over the weakened Philistines—this king inflicted heavy damage on Gath’s walls, among other cities. Around this time, a massive earthquake also struck throughout Israel, as recorded in Amos 1:1. Archaeological evidence for this earthquake has been found all over the Levant, including at Gath. Geologists have estimated it at a magnitude 8.2.

During the reign of Uzziah’s evil grandson Ahaz, the Philistines began once more invading and conquering Jewish cities. The Philistines, by this point, had come under Assyrian dominance. Inscriptions from Assyria show us that the Philistines were invaded around 800 b.c.e. by King Rimmon-nirari and 70 years later by King Tiglath-Pileser (the same time that Tiglath-Pileser was conquering the northern kingdom of Israel).

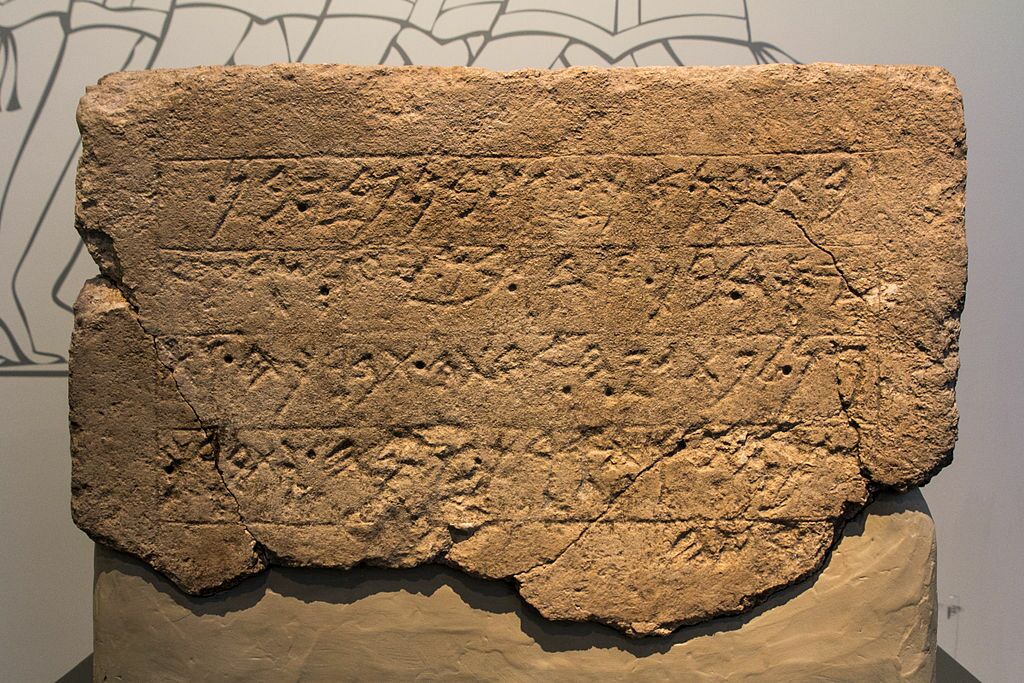

Dating to the following seventh-century b.c.e., a large stone tablet was discovered at Ekron. Significantly, it mentions the name of the city Ekron, along with a lineage of five rulers. One of the rulers mentioned is Achish—the Philistine ruler of Gath during the time of David was also named Achish (1 Samuel 21:10). This would have been a familiar Philistine name, and like Goliath, Alwat, and Wlt, it is not Semitic. One proposal is that it is related to the word “Achaean” (meaning Greek, or specifically Achaean Greek). Assyrian records confirm two of the Philistine leaders on this stone as well, pointing to the heightened Assyrian interests in (and conquests of) the land of the Philistines during this time period.

Destruction and Disappearance

One of the last chronological biblical references for the Philistines is in Jeremiah 47, where the prophet foretells the nation’s destruction by a power out of the north. This is exactly what happened: History records that as the southern kingdom of Judah faced destruction at the hand of Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar, so too did the Philistines. The Philistine land was conquered around 605 b.c.e., and from that point on the warring nation largely disappears from view. Based on Nehemiah 13:23, at least some Philistines of Ashdod survived the invasion and married certain of the Jews. What happened next to this small remnant of surviving Philistines remains a mystery.

Ironically, while the people themselves have disappeared, there is one last controversial vestige of the Philistines that has firmly remained: the territorial name Palestine. Derived from the Philistines’ name, Palestine’s first known use to describe the entire Holy Land was during the fifth century b.c.e., by the Greek historian Herodotus. It would make sense that the name would be first preserved through Greek history—considering the Philistines’ own Aegean origins. Later, in the second century c.e., after crushing the Jewish Bar Kochba Revolt, the Romans officially adopted the name Palestine in order to try to remove the Jewish link to the land.

And so even to this day, conflict continues between the Palestinians and the Israelites (although today’s Palestinians are not physical descendants of the Philistines). The territory that once was the western Philistine state is now the independently controlled Palestinian territory—and even preserves the name of one of the five chief Philistine cities, Gaza.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Assyrians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Babylonians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Canaanites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Egyptians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Hittites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Kushites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Moabites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Persians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Philistines

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Phoenicians