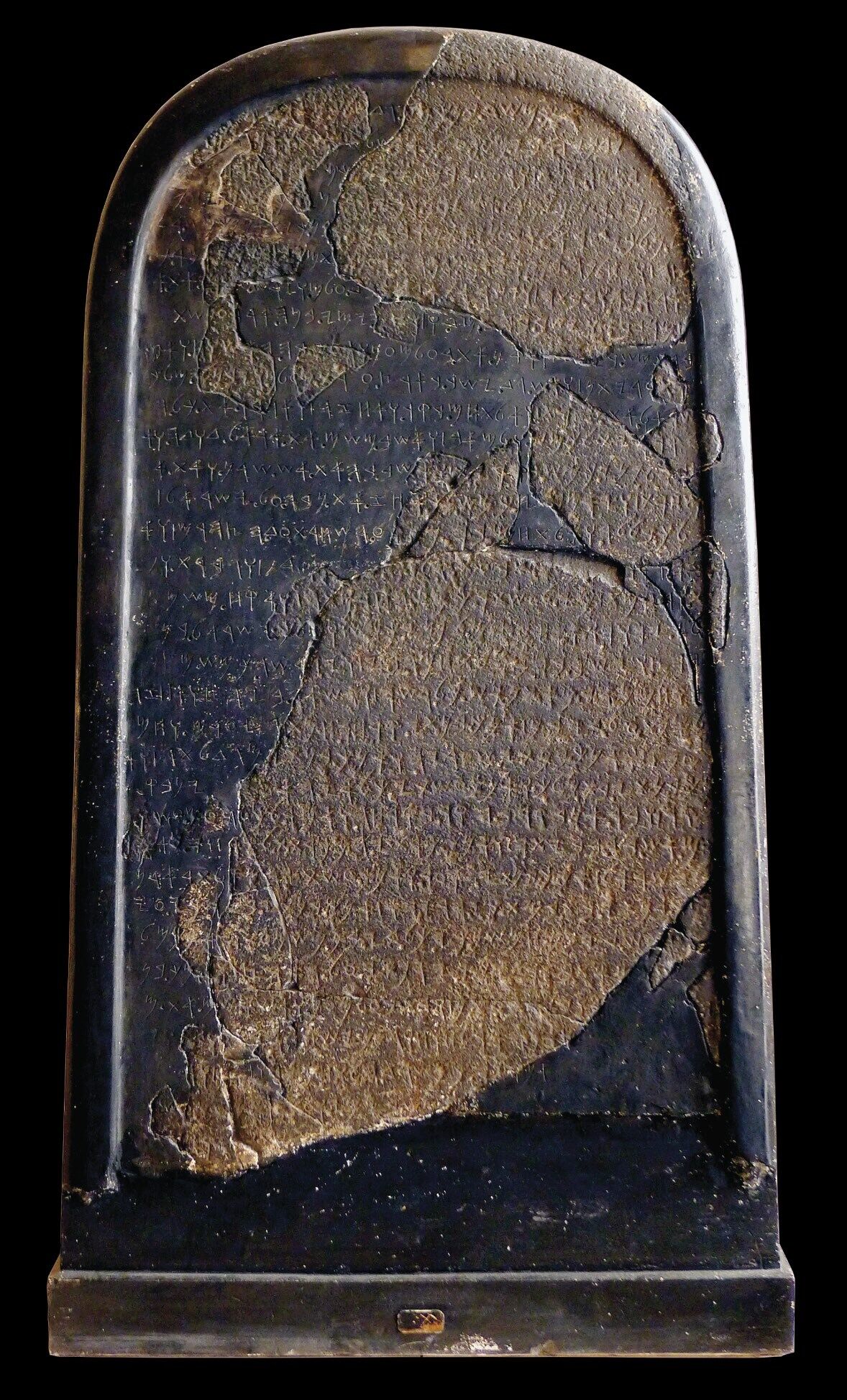

The Mesha Stele (or Moabite Inscription) is a victory relief belonging to the ninth-century b.c.e. Moabite King Mesha. The text on the stele pairs with the biblical account recorded in 2 Kings 3.

This once complete inscription was found in Jordan by local Bedouin and became known to French archaeologist Charles Clermont-Ganneau in 1868. In 1869, Arab intermediaries were sent to the camp to make a “squeeze,” a papier-mâché schematic copy of the impression. Not long after the copy was made, the stele was smashed. The majority of the Mesha Stele was reproduced, thanks largely to Clermont-Ganneau’s “squeeze.” The stele is currently on display in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

In 1992, French epigrapher André Lemaire announced a new reading for Line 31 of the inscription. He claimed that Bet David or “house of David” was the best reading of a part of the inscription. For decades this reading was met with some serious skepticism. However, with the arrival of advanced imaging technology in recent years, the reading of “house of David” has become all but certain according to some scholars, including Prof. Michael Langlois.

In late April, we interviewed Professor Langlois about his research on the inscription and the oft debated topic of King David’s historicity. Here is an excerpt from that interview. This text has been edited for clarity.

Brent Nagtegaal [BN]: Thank you for your time. Let’s get to the meat of the controversy over this inscription, the infamous Line 31. Maybe you could start by telling us about the debate and why there is difficulty in reading this line specifically.

Michael Langlois [ML]: Sure. The difficulty lies in the fact that the stone was broken, so there are a number of pieces that are missing. But before the stone was broken, a squeeze was made of the stone itself. Today we have the squeeze; it is in Paris. And it was the basis used to reconstruct the stone. If you look at the stone today in the Louvre Museum, you will see ancient pieces and also some modern reconstruction.

BN: What do you mean by squeeze?

ML: Well, you take some kind of thin sheet that looks a bit like plaster and basically you apply it over the stone. You wait till it dries, and when it’s dry, you can take it off, leaving an imprint of the inscription. So that’s the idea of a squeeze. … And we have the squeeze, but the squeeze, again, is not perfect. This is because the young boy who made it had to leave before it was dry.

Already in the late 19th century there were a number of proposed readings for the inscription, including one by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau in France, among others. When it came to Line 31, no one agreed on what letters should be read at the end of the line. … So you have a number of possible combinations. But no one thought that one of the possible combinations read “house of David.” This was suggested first by another French scholar, André Lemaire, in the 1990s, just before the discovery of the Tel Dan inscription (which is clearly inscribed with the phrase “house of David”). So the discovery of the Tel Dan Stele confirmed that “house of David” was a possible reading on the Mesha Stele. But somehow a number of people refused to accept this reading.

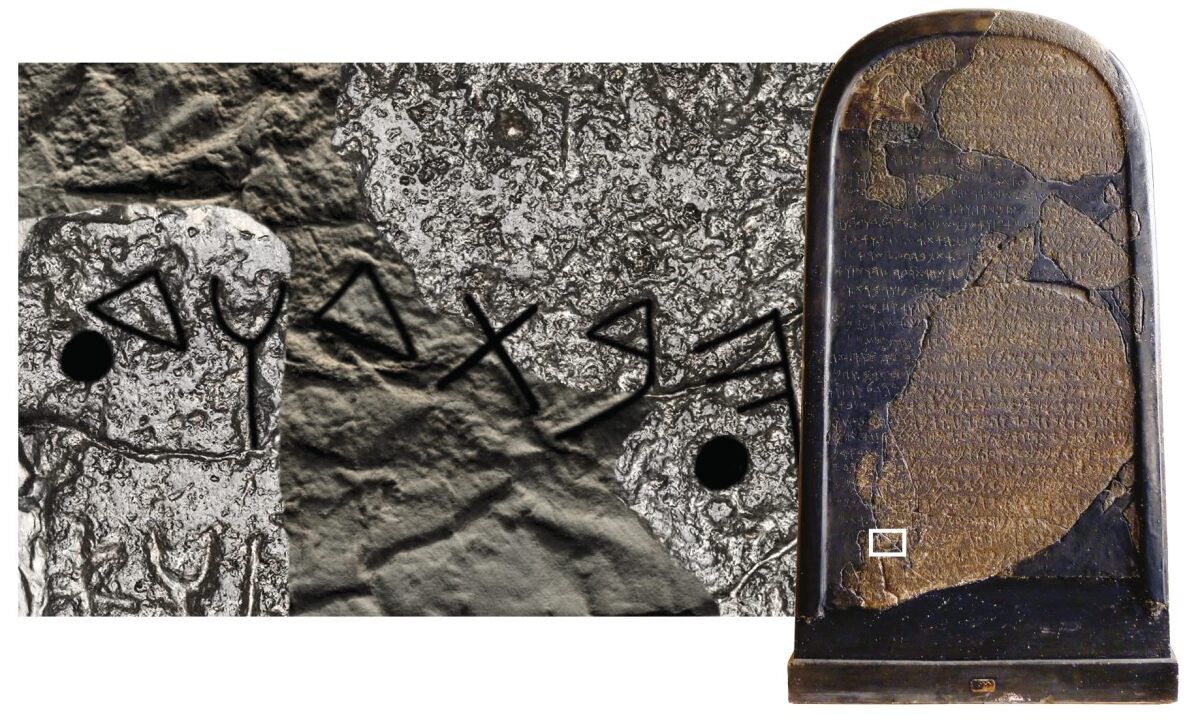

Then when we celebrated the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the Mesha inscription in 2018, I decided to use modern techniques, especially Reflectance Transformation Imaging (rti), to see if I could get a better reading of Line 31 and other lines. When I did that [and restudied the text], I concluded that the only two possible readings that made sense in the context and with the shape of the lines were either Bet David, which means the “house of David,” or Ben David, which is “son of David.” Either way, this text designated the king that was ruling at the time, either calling him a descendant of King David or someone from the house of David, which means the dynasty of David.

BN: I want to take you to a paper that was written five years ago by Israel Finkelstein, Nadav Naaman and Thomas Romer: “Restoring Line 31 in the Mesha Stele, the House of David, or Biblical Balak,” where they suggested it said Balak instead of anything related to David. Did you know about what they were saying or was it just happenstance that it came out as your research was coming out?

ML: No, I didn’t. In 2018 I published a paper presenting my findings with the Mesha inscription, and this is around when their paper was published. I didn’t have time to properly respond to their paper. But I thought that my own analysis was quite conclusive and that I didn’t need to respond to their paper in too much detail.

To make it simple, they made a very, very bad mistake. They looked at the stone itself, and a part of the stone that is reconstructed—that is, they looked at the modern plaster that they put on the stone. They studied the stroke on the modern plaster and said, Look, there is a stroke that says it’s the end of the sentence. One of the elements of the syntax on the Mesha inscription is that sentences are separated by a vertical stroke, which is quite unusual even at the time.

So this is their main mistake: They think that this vertical stroke is part of the stone, but actually it’s part of the modern reconstruction. You can easily see this if you go to Paris or even if you look at pictures of the stone. For this part of the inscription, you have to look at the squeeze (not just the stone)—this is what I did.

I’m a mathematician by training, so I do think systematically. I looked at every possible stroke, every possible letter, every possible combination. And really, Balak is not one of them. There is no natural reading of Balak.

Also, I think it’s interesting that the scholars who complain that we want to read biblical names everywhere outside of the Bible are doing the same thing. Balak is not mentioned anywhere outside the Bible. It’s almost as if they would rather read any name except David.

Following their own line of argument, I could say, Well, as far as I’m concerned, Balak never even existed. He’s a purely fictional character because he’s only mentioned in the Bible. I’m not saying that’s what I’m saying, but this is the typical argument by minimalists who would, you know, disregard any biblical character if they’re not mentioned outside the Bible.

Anyway, they would prefer to read the name Balak, of a character that is only mentioned in the Bible once, rather than what the shape of the letters leads us to conclude. And again, when I read the letters, I didn’t try to read only David. I looked for every possible reading, as you can read in my paper.

I did my best to come up with possibilities other than David. I didn’t try to push for reading David, but that’s the only possible reading. So I was really sad about their paper. And actually, my paper was released shortly after the publication of their paper. They hadn’t consulted with me before they published their own paper. This is unfortunate, because I had the rti photographs that I could have given them. We could have shared our research. I even spoke to one of the people from their team—a student who had been working with them—and I told him this, and even he felt bad. He told me, “I know you’re right. But they wouldn’t listen.” It’s sad.

BN: It doesn’t help that every one of these authors prior to publishing this paper had been on crusade against David. I’m reminded of Prof. Yosef Garfinkel’s excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa and when it was revealed that it was a 10th-century b.c.e. site. Everyone agreed that it’s a 10th-century site, which is the time period of King David. But then many said it could not belong to David and suggested several ethnicities. First it was a Philistine site, then Canaanite, and then an ethnicity we’d never heard of. It could be anything but Judah. And then somebody said, OK, it’s not King David. It’s actually King Saul. This is what you experienced. As a last resort, some scholars will accept it could be a biblical character, just as long as it’s not David, or a figure from the Davidic dynasty.

ML: Yes, that’s a very good example. I remember reading that too.

We’re trying to do solid scholarship and to look at the facts. But again, even when the Tel Dan inscription was published and it was known to say “house of David,” the skeptics had plenty of other explanations. But really, this is a common phrase. It’s the phrase that designates the dynasty of this king. We have this phrase in Akkadian inscriptions, in other inscriptions from the same time period, with other kings from other kingdoms. If this phrase is associated with the kingdom of Damascus or any other place, it’s completely fine; no one will question it.

But there are tensions just because we are talking about Jerusalem and King David. If it were any other place, any other name of any other king, it would be OK. It would be fine.

This is where I see that people are not objective. It’s indicative of the fact that people really don’t want it to be David. They want to find an excuse for it not to be David when, you know, I’m just doing science and that’s what the facts tell me.

I mean, you don’t have to believe everything the Bible says about David. I mean, the faith is something different. Right? I’m not trying to convince people to become believers or anything like that. But for me, it is a fact that there was a kingdom called Judah and then a capital city named Jerusalem, and there was a dynasty, and King David was remembered as the founder of this dynasty. You don’t have to believe the story of David and Goliath. But please don’t remove David completely out of the picture just because you don’t want him to be there. You know, if he’s here, he’s here, and that’s it.

BN: When you reexamined the Mesha Stele using the new technology, you were able to see something no one else had seen. You were able to identify a dot. Why was this important?

ML: Yes, it’s only a dot, so you could say it’s a small contribution. But again, syntax is important. And we talked earlier about those vertical strokes that separate sentences. Dots separate words. I found this dot, which is, again, very helpful to see how many letters you have in that word. So … that’s why I was able to say, you have dalet, vav, dalet—and then the dot, which tells you it’s the end of the word. It’s important because without a dot, you can split words differently.

So the fact that there is this dot is key because it tells us that it is the end of a word. And again, if you don’t have that many words that end with vav, dalet; if you have a dalet before, then the only possible reading is David. So sometimes the minor details are important.

In the Bible, it tells you that if you add or remove a single letter, it makes a difference. In that case, I would say it’s similar to what you read in the Bible; even the tiniest dot makes a big difference. And it was key in the present case.

BN: This is where the Tel Dan Stele connects. Because there is a dot before the Bet, and then there’s a dot after the final dalet of David. You discovered basically the same syntax on the Mesha Stele.

What do your epigrapher colleagues think of your reading? Are they reticent to give their opinion, or have we reached a point of consensus where many agree the Mesha Stele says “house of David”?

ML: Well, I would say that, first, there aren’t that many scholars who are able to discuss those topics because it’s quite technical. There are not that many people who work on ancient Hebrew and Aramaic epigraphy. So there are not that many people I can talk to. But yes, most of them are convinced. I showed the pictures. Some of them wanted me to show them the rti imaging.

Again, I didn’t think it was such a strong [remarkable] discovery, since we have the Tel Dan inscription, which is very clear. So I don’t think my contribution is that big because, for me, it was already clear that we have the “house of David” on the Tel Dan inscription. But of course, the fact that it’s mentioned a second time, at the same time period, is very interesting.

It’s interesting too because it’s written by people from abroad—the king of Moab [the Mesha Stele], the king of Damascus [the Tel Dan Stele]. Those people do not want us to believe in the Bible or to believe in the God of the Bible. They are enemies. They are actually enemies of Israel. And from these inscriptions we see that even the enemies knew at the time that whoever is ruling in Jerusalem is of the house of David. So it tells us a lot about the fame and the fact that there’s a clear hierarchy and dynasty in Jerusalem that is known even to the neighbors, even to the enemies. So in that regard, I think it’s quite interesting that we would have two mentions of the house of David at about the same time.

BN: Yes, I think it’s fascinating. Thank you so much for sticking with it and just going where the scientific evidence led you.