Touring the Bible at Madrid’s National Archaeological Museum

Many centerpieces of Europe’s grand archaeological museums are artifacts uncovered in Middle Eastern expeditions. Blockbuster artifacts like the Louvre’s Code of Hammurabi or the British Museum’s Cyrus Cylinder were not found in the countries they reside in today, but are from the mysterious Orient. Spain’s National Archaeological Museum (Museo Arqueológico Nacional, or man) is different. Its focus is not on exotic relics from Egypt or Iraq, but on local objects from the Stone Age to medieval Islamic rule.

Considering biblical archaeology generally refers to the lands of the Bible (namely the Middle East), one would think man would be an unlikely place to find biblical artifacts. That is what I thought when I visited the museum in May. After all, while the territory we now call Spain is referenced a handful of times in the Bible, the Iberian Peninsula is on the other side of the known world from the Holy Land. However, I was wrong.

Spanish history has a surprising connection to the Bible—and the local artifacts in Spain’s archaeological museum can affirm this. While there aren’t any artifacts like the Mesha Stele or Sennacherib’s prisms, there are plenty of artifacts reflecting general cultural practices that correlate with those described in the Bible.

The Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology has written on the extensive collections of the British Museum and the Louvre. Now, it’s time to explore the history at Madrid’s National Archaeological Museum.

From Tartessos to Tarshish

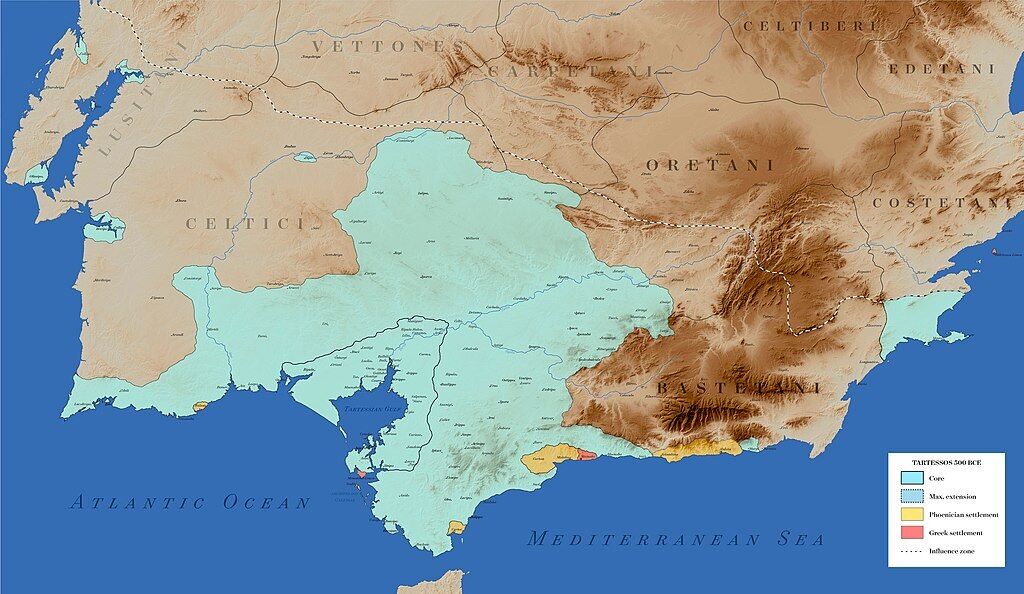

The museum’s collection starts with displays from Spain’s “prehistoric” and Bronze Age civilizations. Compared to the eastern Mediterranean (the land of the Bible, as well as places like Egypt and Greece), Spain has relatively little to show for these periods. But in the Late Bronze Age, we start to see the development of an enigmatic civilization in Spain’s southwest. This would be the land of Tartessos.

Herodotus wrote in the fifth century b.c.e. that Tartessos was past the Pillars of Hercules, in southwestern Spain (The Histories, Book 4, 152). Strabo, writing in the first century b.c.e., claimed the Greek underworld Tartarus was named after Tartessos on account of Tartessos being the furthest westerly point of the known world. He also wrote that the region around Tartessos, and Spain in general, was very plentiful in silver and other wealth (Geography, Book 3, 2.11-13). Both historians state the Greeks and Phoenicians discovered and settled “Iberia,” including Tartessos (Histories, Book 1, 163; Geography, Book 3, 2.13). This description fits remarkably well with the Bible’s description of a mysterious occidental land called Tarshish.

Genesis 10:4 describes Tarshish as an affiliated people of Javan (the biblical name for the Greeks). 2 Chronicles 9:21 specifies that Tarshish was a zone of Phoenician colonization under Hiram (“Huram”), king of Tyre and an ally of Israel’s King Solomon. The chronicler writes that the “ships of Tarshish” would import “gold, and silver, ivory, and apes, and peacocks” to the Middle East, suggesting not only that Tarshish was a source of wealth, but that it had proximity to Africa. (Where the peacocks fit in, if this is an accurate translation, is anybody’s guess. But, perhaps surprisingly, there is a variety of peafowl found in Central Africa.) Jeremiah 10:9 specifies silver trade as a Tarshish specialty. According to Jonah 1:3, when Jonah was trying to flee God’s commission to go to the city of Nineveh in northern Iraq (northwest of Israel), he found a ship sailing to Tarshish, implying that Tarshish was about as far in the opposite direction as one could get from Nineveh (compare with Jonah 4:2). That Jonah was able to get a ship from Joppa (modern-day Tel Aviv) to Tarshish so easily may imply there was regular traffic between Tarshish and the Levant.

Thus, Tartessos is a good fit for biblical Tarshish.

The Warrior Stelae

Strange stelae, dating to the Late Bronze Age, were discovered in southwestern Spain. These stelae depict various warrior figures, sometimes shown wearing a horned helmet, or equipped with other instruments of war, such as swords, spears and shields. Over 100 of these stelae have been discovered.

In one such stele, the warrior is shown with a Mediterranean-style chariot. The image, however, is erroneous: The wheels should not be placed on the axis. Archaeologists suspect whoever designed the stele never saw a chariot for himself. In other words, the motifs of the stele have influences from abroad—specifically, from the east. The stele was found in the Cáceras province, closer to Madrid and the center of the country, rather than the southern coast.

It is important to note that “Bronze Age” means different years in different parts of the world. It is generally defined as between the time from mass production of bronze objects to mass production of iron objects. In the Middle East, the Bronze Age is generally dated from about 3000 b.c.e. to 1200 b.c.e. But in much of Europe (including Spain), the Bronze Age isn’t considered to have ended until well into the first millennium b.c.e.

Scholars date these “warrior” stelae to the ninth and eighth centuries b.c.e. (900–700 b.c.e.), the time immediately after Kings Solomon and Hiram would have been on the scene (mid-900s b.c.e.). Many skeptics of the biblical account believe the Phoenicians did not start colonizing Spain until several centuries after Solomon, beginning around the year 800 b.c.e. The warrior stelae show cultural influence with the rest of the Mediterranean world potentially as early as a century before that. And considering the iconography would have been familiar to the ancient Iberians before the stelae were set up, the stelae could imply an even earlier cultural exchange. The fact that some of the stelae were found so far inland suggests how pervasive this influence would have been.

Meanwhile, stelae depicting similarly-designed horned figures have also been found in the Mediterranean. A stele found in Bethsaida in northern Galilee, dated to the mid-to-late eighth century b.c.e., is the only example found in the Holy Land. But two similar stelae have been found in southern Syria, and one in Harran in southern Turkey. Scholars estimate these stelae are supposed to depict some sort of Levantine pagan deity.

The Gods of Phoenicia

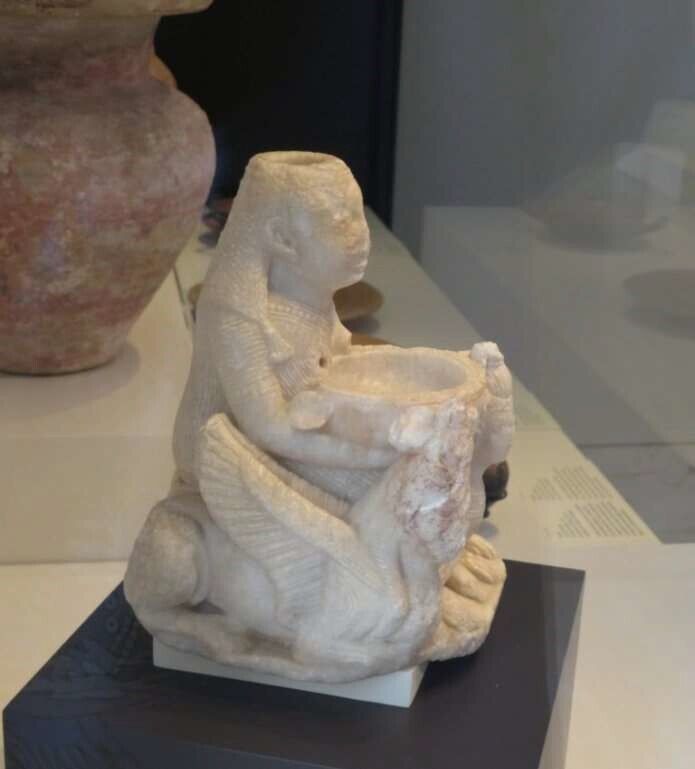

As time progresses into the first millennium b.c.e., Phoenician influence in southern Spain becomes more obvious. Among the most obvious evidences of colonization are idols and other religious objects relating to the Phoenician pantheon. These include the so-called “Lady of Galera,” identified as the goddess Astarte (referred to as “Ashtaroth” in Judges 2:13 and elsewhere). The small sculpture is made of alabaster and dates to the eighth century b.c.e. 1 Kings 11:5 specifies “Ashtoreth” (a variant spelling) as “the goddess of the Zidonians,” or the inhabitants of Sidon—another major Phoenician city-state. Archaeologists believe the Lady of Galera was originally made in a Syro-Phoenician workshop, imported to Spain, and eventually deposited in an Iberian tomb in the late fifth century b.c.e. near Granada.

Also exhibited at Madrid’s archaeological museum are several representations of Astarte’s notorious consort: Baal. The thunder god of the Canaanites, Baal is the pagan deity whom God perennially corrects Israel for following (i.e. Numbers 25:3; Deuteronomy 4:3; 1 Samuel 12:10). 1 Kings 16:31 links Baal worship with Israel’s Phoenician-born queen, the infamous Jezebel. This figurine is thought to represent Baal syncretized with the god Reshef.

Baal and Astarte were worshipped throughout the Levant. But Tyre’s most prominent god was a local one. Melqart (whose name means “king of the city”) was the patron deity of Tyre. According to World History Encyclopedia, “Melqart was considered by the Phoenicians to represent the monarchy, perhaps the king even represented the god, or vice versa, so that the two became one and the same.” In Ezekiel 28, God instructed the Prophet Ezekiel to chide with the king of Tyre for claiming he is a god, “sit[ting] in the seat of the gods” (verse 2; Revised Standard Version).

Such religious influence shows what the Phoenicians brought to Spain. But what did they come to receive? The Bible’s account of Solomon’s trade networks tells us that Tarshish was a source for, among other commodities, precious metals. “And all king Solomon’s drinking-vessels were of gold, and all the vessels of the house of the forest of Lebanon were of pure gold; silver was nothing account of in the days of Solomon. For the king had ships that went to Tarshish with the servants of [Hiram]; once every three years came the ships of Tarshish, bringing gold, and silver” (2 Chronicles 9:20-21).

The Gold of Tarshish

Some of the most exquisite objects found in ancient Tarshish are various examples of goldwork. Golden candlesticks pictured below are believed to represent a deity related to trees. They date from between the eighth and seventh centuries b.c.e. and were found near Seville.

A golden belt discovered in a funerary trove depicts a hero (identified as Melqart) fighting a lion, along with the characteristic Phoenician sphynx. Like some of the warrior stelae, this belt was found far inland.

The Bible mentions Solomon hiring Phoenician craftsmen and utilizing Phoenician supplies in constructing God’s Temple in Jerusalem. Gold isn’t mentioned as a commodity he requested from the Phoenicians, per se. Yet gold was a vital part of the Temple: “And the whole house he overlaid with gold, until all the house was finished; also the whole altar that belonged to the sanctuary he overlaid with gold” (1 Kings 6:22). The Bible states that King David had gold collected before Solomon’s reign (1 Chronicles 22:14). Considering Israel’s trade links with Tyre, it is logical that some of this gold could have come from Tarshish.

Shekels of Silver

With Phoenician business came Phoenician business practices. Historians believe the first official minted currency in the ancient Mediterranean was in sixth century b.c.e. Lydia (modern-day Turkey). This would have been well after the time of Hiram and Solomon. Hacksilver proceeded minted coins. The silver’s value was based on the weight of the collective hoard of silver fragments. For example, in Genesis 23:16, Abraham purchased a plot of land for 400 shekels, a shekel being a unit of weight roughly equivalent to 9 grams.

Spain’s National Archaeological Museum displays the “Driebes Hoard,” found just outside Madrid. According to the museum, the hoard of hacksilver was hidden in the late third or early second century b.c.e. by the Carpetani, a pre-Roman Celtic group in the Iberian Peninsula. The hoard shows that hacksilver was still being used well into the first millennium b.c.e.

As society developed during what we call “classical antiquity,” the use of hacksilver gave way to coins and official currency. Meanwhile, as the Phoenician heartland in modern Lebanon fell subject to foreign rulers, the colonies in the western Mediterranean banded together to form a new civilization: ancient Carthage. Based in North Africa, the Semitic-speaking Carthaginians controlled much of southern Spain until the Roman conquest.

Like their contemporary Greeks and Romans, the Carthaginians minted their own coins. But old habits apparently die hard. Spain’s archaeological museum has several examples of their currency—a silver coin they called a “shekel.”

The Pozo Moro Monument

The man’s centerpiece is the Pozo Moro Monument, a massive sixth century b.c.e. mausoleum constructed with ashlar stones and covered in religious iconography, originally found disassembled in a necropolis near Valencia. The structure may have had a second story and may have been as much as 10 meters (about 32 feet) tall. Much of the current edifice is reconstructed. Scholars are divided as to whether it was built by Phoenicians or native Iberians. But the mausoleum certainly has Near Eastern influence.

One of the most intriguing reliefs is on the sixth row of the monument’s east side. Depicted on the right of the following image is a monster or demon of some sort holding a knife. Directly in front of him is a small figure on a pedestal interpreted as a child ready to be sacrificed. On the left of the image is another supernatural being with a child in a bowl, apparently about to be devoured. Child sacrifice was one of the grislier sins God condemned the Israelites for partaking in. Deuteronomy 18:10 forbade the Israelites from “[making] his son or his daughter to pass through the fire,” meaning to sacrifice to a pagan god. Verse 9 states that such a practice was among “the abominations of those nations [in the land before the Israelites].” This included the Phoenicians.

Another relief on the west side depicts a goddess with stylistic similarity to the Egyptian sky goddess Hathor. Behind her wing is a tree with a curiously curved top.

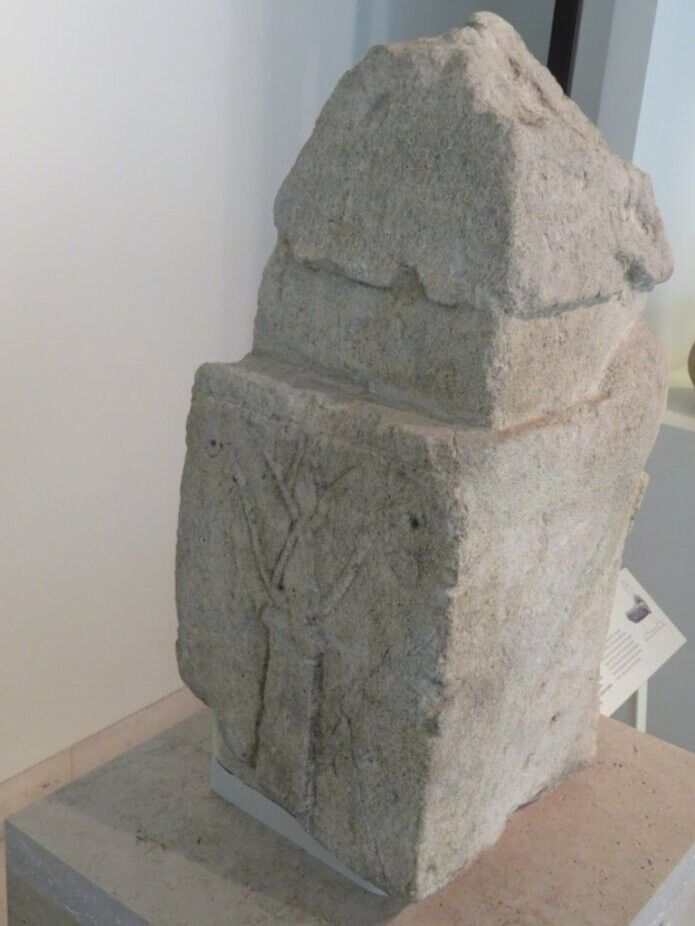

Compare with the man’s fifth century b.c.e. funerary stele from Andalusia: A motif similar in design to the tree on the Pozo Moro Monument is found on the back of the stela. The man identifies this symbolism as representing a “tree of life.”

Trees with a curved top evidently were common themes in Phoenician art. At the “Large Stone Structure” (an Iron Age settlement in ancient Jerusalem identified as the palace of King David), a similarly designed column capital was discovered by Kathleen Kenyon in 1963. These so-called “proto-Aeolic” capitals have been found all over the Levant. But the Bible lists Hiram’s Phoenicians as the constructors of David’s palace (2 Samuel 5:11). The Phoenicians evidently brought their artistic tastes with them when they sailed to Spain.

Biblical Archaeology in Spain

Pagan idols and human sacrifice may not be the most inspiring aspects of biblical archaeology. But Spain’s National Archaeological Museum collection illustrates a remarkable truth: Spain—on the other side of the known world from Israel—would probably be the last place anybody would expect to find significant biblical archaeological remains, yet so much of early Spanish history can be explained by using the Bible. Many of the objects in the man’s collection would probably be hard to interpret otherwise.

The Bible is a book primarily about the people of Israel. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be used to explain history—even foundational history—in other parts of the world. The displays at the Museo Arqueológico Nacional demonstrate this. And in this sense, even if the history displayed points to aspects of the past not particularly admirable, the Bible becomes a great unifier of mankind. In this sense, the Bible becomes the foundational text of many more civilizations than meets the eye. This includes the Spanish.