Sisera v. Deborah: Evidence for the Biblical Account

It’s one of the great (albeit lesser-known) conflicts of the Bible—and a rare one in that it features leading female protagonists: Deborah and Jael (Yael in Hebrew).

During the period of the judges, Israel had fallen victim to the Canaanite King Jabin and his mighty commander Sisera, who exerted a 20-year reign of oppression over the Israelites. Under the guidance of the Prophetess Deborah, the commander Barak led 10,000 Israelites against Sisera’s force of 900 iron chariots and a vastly superior number of troops. The Israelites defeated the Canaanites, and the fleeing Sisera was killed in his sleep by Jael, who drove a tent peg through his head. The full story is recounted in Judges 4-5.

It is certainly a dramatic account. And along with several other early biblical accounts, it is often dismissed as fictional. But is there any material evidence on the ground for it? This article begins our new series on the evidence for the conflicts in the book of Judges. Let’s examine the text in detail, alongside several relevant discoveries.

Historical Context

“And the children of Israel again did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord, when Ehud was dead. And the Lord gave them over into the hand of Jabin king of Canaan, that reigned in Hazor; the captain of whose host was Sisera, who dwelt in Harosheth-goiim.” (Judges 4:1-2). Biblical chronology roughly places this Canaanite subservience and ensuing battle sometime around the late 13th century b.c.e. Here we are introduced to Israel’s oppressor: the Canaanite king of Hazor, Jabin.

This name is noteworthy in that Jabin is also the name of a Canaanite king of Hazor during the 15th- to 14th-century b.c.e. invasion of Canaan during the days of Joshua. Some have wondered if the stories are somehow mixed up and conflated. But a discovery has shed light on the matter. As Prof. Douglas Petrovich writes (emphasis added):

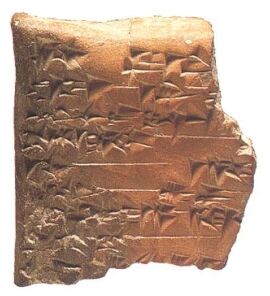

The tension [with regard to the “Jabin” question] dissipates, however, once the reader understands that the term “jabin” is not the name of the king, but rather is a royal, dynastic title. [T]he use of this ancient name dates back to the Mari archives of the 18th century b.c.e., where Yabni-Adad is mentioned as the king of Hazor [“Yabni” is the exact Mari equivalent of the biblical Hebrew “Yabin,” which is anglicized to “Jabin”]. The proposal of a dynastic use of “jabin” for the king of Hazor in both Joshua and Judges thus has sufficient merit ….

Thus we have a precedent established for the use of the title Jabin for Canaanite kings at Hazor.

As excavations at this city have revealed, Hazor would have been a logical place for a powerful Canaanite dominion over a broad territory of Israel. Joshua 11:10 reveals that “Hazor beforetime was the head of all those kingdoms [of Canaan].” This was the chief Canaanite seat of authority. Excavations have confirmed that during this time period, Hazor was the biggest city in the region, with an estimated population of around 20,000 inhabitants within the upper and sprawling lower city (still largely unexcavated).

Sisera’s Chariots

Jabin’s captain, Sisera, was stationed in a place named “Harosheth of the Gentiles.” He commanded a jaw-droppingly powerful force of “nine hundred chariots of iron.” This kind of strength in the region is laughable—until the historical context is considered.

First, Harosheth. The late archaeologist Prof. Adam Zertal linked this location to the modern site of Ahwat, in northern Israel. During his excavations there (1993–2000), the team uncovered a Bronze Age city dating to the 13th to 12th centuries b.c.e. Within a structure known as the “Governor’s House,” the archaeologists discovered a broken bronze chariot linchpin, molded to depict a female face wearing chariot wheel earrings. Such linchpins would keep the chariot wheel from coming off the axle. Ancient artwork (such as below) show that such ornate linchpins would typically adorn the chariots of high-ranking individuals.

The “chariot” setting is further emphasized when considering the wider historical context of this period.

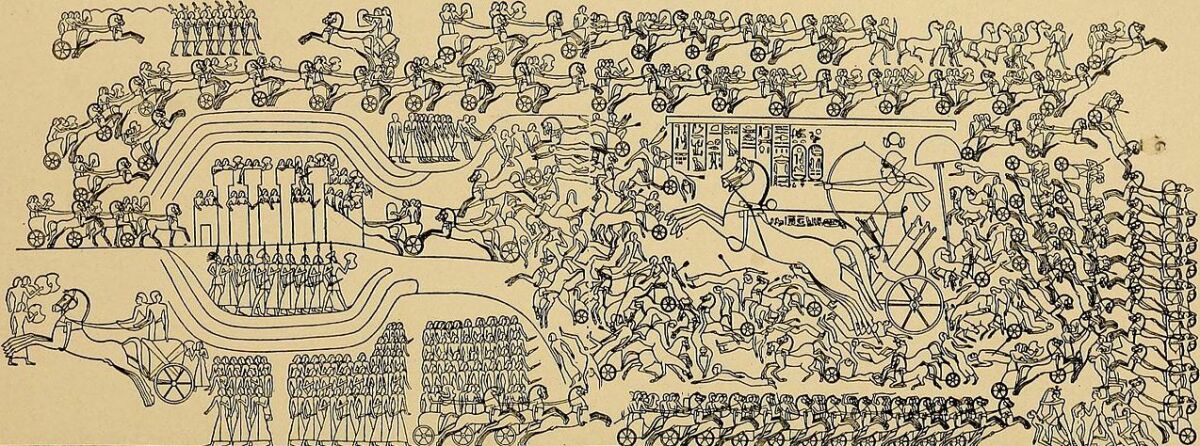

The Battle of Kadesh, fought between the Egyptians and the Hittites in the 13th century b.c.e. at the modern-day border of Lebanon and Syria, is the “best documented battle in all of ancient history.” Inscriptions relating to this battle contain the earliest known information (outside of the Bible) about battle formations and military tactics. It also happens to be known as the largest chariot battle ever fought. The Egyptians wielded a force of around 2,000 light, nimble chariots against a Hittite force of heavy chariots, with force estimates varying wildly from 2,500 to 10,500.

The outcome of the battle, dated circa 1275 b.c.e., is still actually debated—due to the fact that most of our understanding of it comes from biased Egyptian sources. The battle did end with a peace treaty, but both sides claimed victory. Scholars believe that the Egyptians secured more of a “victory” in morale from the battle, but in practical terms the Hittites were the real victors—continuing to possess and dominate the region following the Egyptian departure. It is unclear how much territory Egypt continued to control north of Canaan.

This battle would account for a never-before-seen flush of chariots in and around this contested region surrounding Canaan. And this is what we see in the biblical account of Sisera’s troops—perhaps several decades after the Battle of Kadesh: a military leader commanding a massive force of 900 chariots.

There is plenty of debate about the identity of Sisera himself—from the name being Hittite to being Egyptian. Professor Zertal speculates that Sisera might have been part of the Mediterranean “Sea Peoples” force known as Sherden or Sherdana, possibly originating from the island of Sardinia. Zertal points out that the architecture of Ahwat (Harosheth of the Gentiles?) resembles that found in Sardinia. The Sherden are known for fighting against the Egyptians, but the pharaoh also reportedly used them as mercenaries in his fight at the Battle of Kadesh.

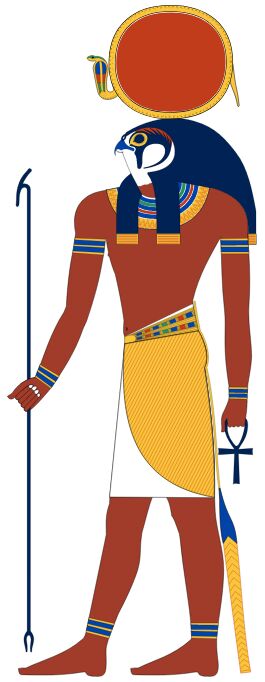

One suggested meaning behind the captain’s name is the Egyptian title “Ses-ra,” meaning “servant of Ra.” Ra was one of the four Egyptian chariot divisions used at Kadesh; perhaps Sisera was a Sherden mercenary fighting in this division.

The biblical description of Sisera’s “iron chariots” would favor the heavy Hittite chariots. As such, perhaps this leader came into possession of the many Hittite chariots that were reportedly abandoned during the battle. We can only speculate. Still, the wider picture of a massive biblical chariot army fits perfectly with this specific historical period.

The Battle

The battle between the two forces took place at Mount Tabor, an imposing hill in the north of Israel, at the end of the Jezreel Valley. God commanded Barak, through the Prophetess Deborah, to take 10,000 Israelite soldiers up the mount and draw Sisera’s troops toward him and the River Kishon.

Barak refused to go without Deborah. “And she said: ‘I will surely go with thee; notwithstanding the journey that thou takest shall not be for thy honour; for the Lord will give Sisera over into the hand of a woman.’ And Deborah arose, and went with Barak to Kedesh” (Judges 4:9).

Sisera rallied his men and chariots to the nearby River Kishon, and Barak attacked from the height advantage, charging down the mount. “And the Lord discomfited Sisera, and all his chariots, and all his host, with the edge of the sword before Barak; and Sisera alighted from his chariot, and fled away on his feet” (verse 15). The chariots, evidently bunched up and hemmed into a tricky position, were overcome by the Israelite troops.

The fleeing, weary Sisera eventually came to the tent of a Kenite chief named Heber, where his wife Jael was at home. (The Kenites and Israelites were allied; however, there was also an alliance of peace between this Kenite household and Jabin—verse 17). Seeking safety, Sisera entered the tent and asked Jael for protection. Jael gave the captain a bottle of milk, hid him, and after he was sound asleep, took out a hammer and tent peg and skewered him through the temples into the ground. “And, behold, as Barak pursued Sisera, Jael came out to meet him, and said unto him: ‘Come, and I will show thee the man whom thou seekest.’ … So God subdued on that day Jabin the king of Canaan before the children of Israel” (verses 22-23).

Currently, no excavations have taken place to reveal the site of the battle itself. However, related evidence is elsewhere. “And the hand of the children of Israel prevailed more and more against Jabin the king of Canaan, until they had destroyed Jabin king of Canaan” (verse 24). Jabin, of course, was established at the powerful fortress of Hazor. In order to utterly defeat Jabin himself, ruling for 20 years from the site, an assault on Hazor must have been necessary. And dating to this same time period—the late 13th century b.c.e.—is a thick layer of burning and destruction. The city had clearly been overthrown by someone, and the utter destruction described in verse 24 matches the nature of the destruction found at Hazor.

Song of Deborah

Following the biblical description of the battle is the “Song of Deborah.” Judges 5 describes, in poetic form, additional details in the story, given by Deborah and Barak. They praise certain Israelite tribes that assisted in the effort to overthrow Jabin, and they condemn those that didn’t. And there are a number of interesting speculative tidbits.

In verses 6-8, they bemoan the previous state of the land—poverty, oppression, idol worship—not a “shield or spear seen among forty thousand.” This perfectly sums up the status quo found at Iron i sites all across Israel. Archaeologists excavating “judges”-period Israel often categorize their finds as Canaanite, or proof against an early, biblical Israelite establishment. Some scholars even claim that the 13th-century b.c.e. destruction layer found at Hazor represents Israel’s “conquest” of Canaan, because the earlier material culture is so poor, or reflects a “Canaanite” status quo. Actually, these discoveries reinforce the biblical account. (Plus, a destruction layer at Hazor, dating some 150 years earlier, matches with the biblical chronology of the Israelite conquest of Canaan.) Israel, throughout the period of the judges, was repeatedly brutalized, oppressed, downtrodden and harassed by the prevalent Canaanite colonies (Judges 3:1-7). This was especially the case during this period under the rule of Jabin: “the highways ceased … The rulers ceased in Israel, they ceased” (Judges 5:6-7). The view that the Israelites were simply Yahweh-worshipers is overly simplistic: This passage of scripture, and numerous others, highlight Israel’s affinity for pagan gods.

Verse 19 of Deborah’s song reads, “The kings came, they fought; Then fought the kings of Canaan, In Taanach by the waters of Megiddo ….” This is a peculiar passage: Who were these kings fighting? Could this be a reference to an earlier “battle of kings”—the major Battle of Kadesh between the regional superpowers led by kings Muwatalli ii and Ramesses ii? And could the aftermath of this conflict have led to some kind of vacuum filled by fighting Canaanite kings, eventually filled by King Jabin, who subsequently oppressed the land for 20 years, allied with the regional chariot-commander Sisera?

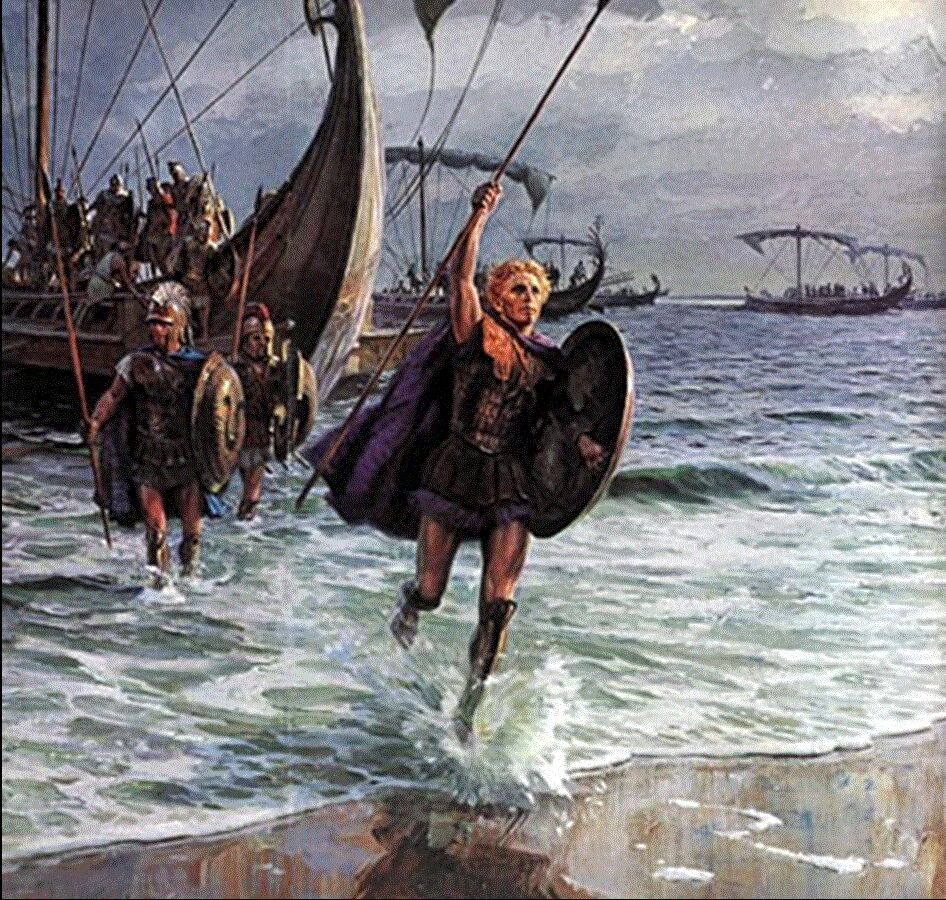

One of the tribes condemned for not joining Israel’s fight was the tribe of Dan. “And Dan, why doth he sojourn by the ships?” Deborah asked (verse 17). This small sentence reveals an otherwise unknown detail about the Danites: They were a seafaring tribe. They were otherwise occupied in their ships, rather than helping their fellow Israelites in this battle. And at this same time period, there is attestation to a similarly named, similarly cultured sea-faring group occupied elsewhere “in their ships.”

The Trojan War has long been seen as a simple mythical account, largely propounded by Homer, but archaeological excavations over the past century have been challenging that assumption. The battle—which chronologically occurred around this same time period (circa late 13th century b.c.e.)—was fought by numerous different Mediterranean tribes against Troy/Ilios (identified as the modern site of Wilusa). One significant group contributing to the fight was a sea-faring force known as the Danaoi (also Danaan). The Danaoi/Danaan have been linked to a mysterious Levantine people called the Denyen. Late archaeologist Prof. Yigael Yadin posited that these were one and the same as the tribe of Dan. Remains from the “capital city” of the Danites, Tel Dan, show heavy Greek-Mycanaean influence (and there are numerous material and textual links between the Danite and Mycenaean worlds). Could the biblical Danites, preoccupied “on their ships” in the late 13th century, have been the Danaoi on their ships in the late 13th century b.c.e.—engaged in military matters elsewhere, rather than assisting their fellow embattled Israelites?

An interesting detail in the “Song of Deborah”: The battle of Tabor is unique in that angels are described fighting alongside the Israelites. “They fought from heaven; the stars [biblical symbolism for angels] in their courses fought against Sisera” (verse 20; hence, the imagery in the famous cover-art of Luca Giordano).

One of our readers lives in a house overlooking this site of battle. She wrote to us, noting the swampy nature of the Jezreel Valley and the wild-flowing Kishon River in and around the winter time—the rainy season. As such, it would have made the most sense for Sisera to bring out his chariot force during the summer months, when the ground was dry and compact, and the river a comparative trickle. The Kishon River is mentioned directly following the passage about heavenly help in battle:

They fought from heaven, the stars in their courses fought against Sisera. The brook Kishon swept them away, that ancient brook, the brook Kishon. (Judges 5:20-21)

It would thus appear that a sudden, miraculous, unseasonal downpour played a major role in the defeat of Sisera and his heavy iron chariots—the Kishon bursting its banks and bogging down the chariots into a helpless melee. This would also help explain why Sisera dismounted from his ordinarily swift chariot, and fled on foot (4:15).

Continuing in her song, Deborah continues to describe Sisera’s mother pining for her son, waiting for him to return to her. Deborah: “Through the window she looked forth, and peered, The mother of Sisera, through the lattice: ‘Why is his chariot so long in coming? Why tarry the wheels of his chariots?” (verse 28).

This “lady in the window” is a repeated theme in the Bible and in archaeology. The same imagery is found in the story of Jezebel (2 Kings 9:30). It is depicted in different ways in ancient art form, but most famously in a set style of engraved ivories, including an example found at the Israelite capital Samaria and a Phoenician example found at the Assyrian capital Nimrud. This form depicts a woman with Egyptian-style hair, in a motif probably connected in some form to the goddess Astarte, or Ishtar (worshiped heavily throughout the Levant).

“So perish all Thine enemies, O LORD; But they that love Him be as the sun when he goeth forth in his might. And the land had rest forty years” (Judges 5:31). So concludes the “Song of Deborah.”

The Body of Evidence

Archaeology has not proved the existence of the individual characters themselves: Deborah, Barak, Jael, Sisera and Jabin. But the wider biblical account fits beautifully with the evidence from the historical period:

- A predominant Canaanite influence across Israel,

- Worship of Canaanite idols throughout the land,

- The largest-recorded chariot battle in history occurring just north of the Holy Land—fitting right behind the biblical account of a force of 900 chariots in the region,

- Evidence for the presence of royal chariots at the city of Ahwat,

- Evidence for Hazor’s dominance as a chief Canaanite city,

- Evidence for the Hazorite title “Jabin,”

- Evidence for the destruction of this city, at the time period of the biblical overthrow of Jabin,

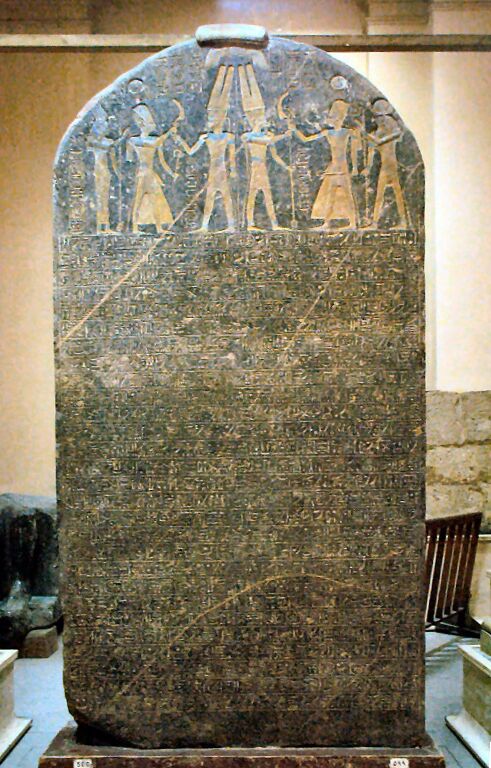

- And evidence for Israel’s eventual rise in national standing, following this oppressive period—with the reference to the nation by the Pharaoh Merneptah on his stele, circa 1205—and the transition into Iron iia period of the kings of Israel (circa 1000 b.c.e.).

The period of the Israelite kings, from circa 1000 to 586 b.c.e., is well attested to in archaeology. But now, we also have an emerging body of evidence for the nation of Israel’s earliest history in the Holy Land: the tumultuous, lesser-known—but fascinating and formative—period of the judges. A bloody period intended to highlight the pitfalls of relativism and following one’s own moral compass. As the book concludes and summarizes in Judges 21:25: “In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did that which was right in his own eyes.”

Articles in This Series:

Othniel v. Chushan-Rishathaim: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Ehud v. Eglon: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Shamgar v. the Philistines: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Sisera v. Deborah: Evidence for the Biblical Account