Genesis 14: Uncovering the Bible’s World War I

The Battle of Megiddo, fought between Pharaoh Thutmose iii and Canaanite city-states circa 1482 b.c.e., is often described as the “first battle in history.” This isn’t true, of course. This is simply the earliest battle for which details are widely accepted as reliable by scholars.

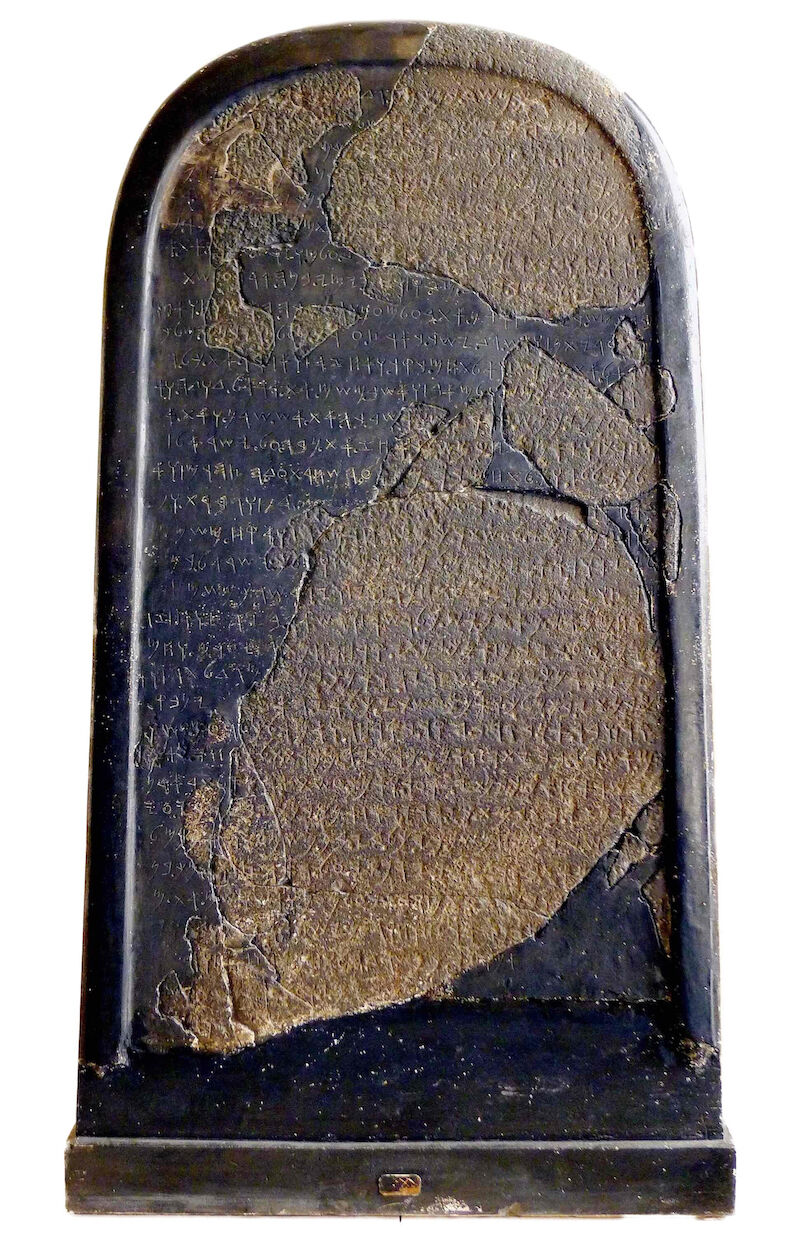

Yet there is another account of a battle centuries earlier—a battle for which we have comparatively detailed information, including the identities of multiple nations and the names of 13 different leaders. It is a battle for which we have detailed campaign maps, including routes of attack, escape and topographical challenges; particulars about guerrilla tactics and intervention; conflict resolution and distribution of spoils. There is even a description of familial relations and household organization. All of this information is contained in 340 words of ancient Semitic text—the translation of which equates to around 600 words in English. (By way of comparison, this text is nearly seven times the length of that preserved on the Tel Dan Stele and around a third longer than that of the Mesha Stele.)

For many scholars, there’s just one “problem” with this account: It is found in the Bible. Not only that, but in the most historically “suspect” book of them all—Genesis.

Bible scholar Mary Jane Chaignot summarized this skepticism towards Genesis 14 as an account “almost monotonous in its detail of names and places, none of which can be verified by outside biblical sources. That makes scholars nervous. … [I]t raises many unnerving questions about the historicity of the whole chapter. Like, maybe it really isn’t true, after all” (“Genesis 14: Abraham and the Four Kings”; emphasis added throughout).

While some historical and archaeological particulars are lacking, this assessment could not be further from the truth. There is in fact a strong body of evidence, not only for the general geopolitical situation at the time of this conflict but also the identity of several of the antagonists themselves.

In this article, we’ll review the “real” first world war—the epic “Battle of Nations” recorded in Genesis 14—and the extraordinary evidence for it.

Overview

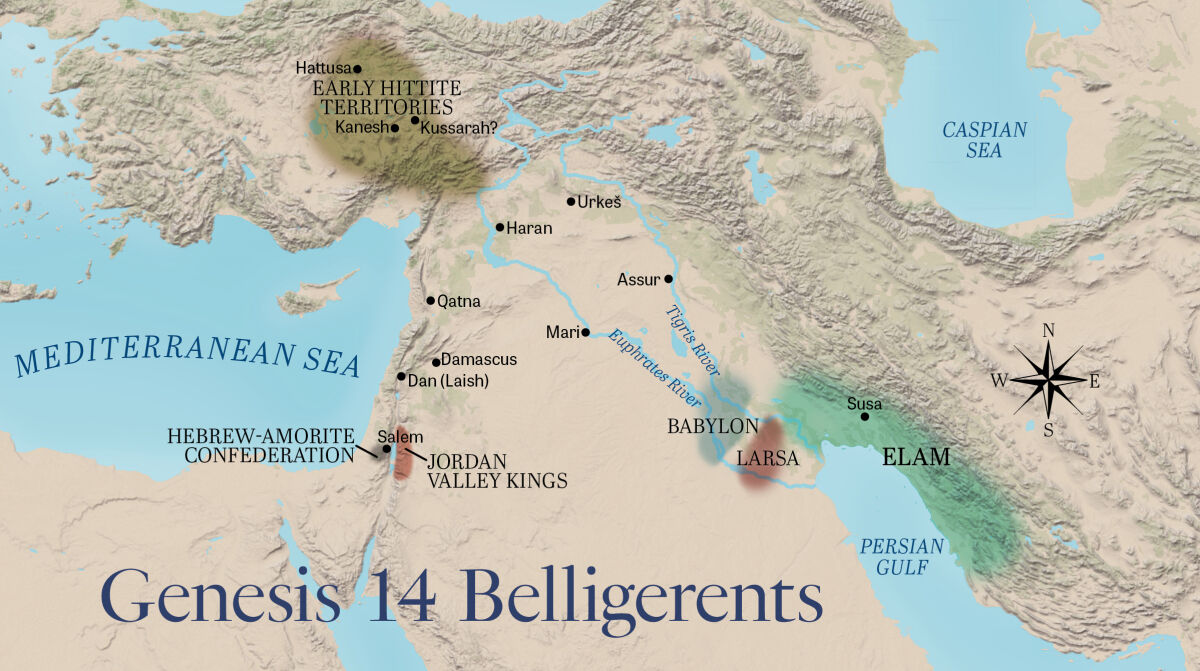

The Genesis 14 account takes place within the lifetime of Abram, during the early part of his sojourn in Canaan. The chapter begins by describing a coalition of four powerful polities, led by the Elamite king Chedorlaomer. This king advances against a rebel alliance of five city-states located in the Jordan Valley-Dead Sea region.

The Bible describes the four-king eastern axis as handily defeating the five-king Transjordanian bloc and carving for themselves an even wider path of destruction throughout the Southern Levant. Among the spoils of war gleaned from the lavish city of Sodom was Abram’s nephew Lot, including his family and possessions.

When Abram heard of Lot’s capture, Genesis 14:14 says that he rallied “his trained men, born in his house, three hundred and eighteen, and pursued as far as Dan” (a city called Laish during Abram’s time—Judges 18:29). From there, Abram’s forces attacked the invaders in guerrilla fashion by night, routing the armies on their return journey up into Syria, and ultimately forcing the release of the captured booty and slaves. “And he brought back all the goods, and also brought back his brother Lot, and his goods, and the women also, and the people” (Genesis 14:16). The chapter concludes with a description of Abram’s triumphant return and his exchanges in the “King’s Vale” with Melchizedek (king-priest of Salem) and Bera (king of Sodom).

Situating the Conflict

In investigating the historicity of the account, we must first establish the time frame of these biblical patriarchs. This can often be the most controversial issue, but we shall see, based on the convergence of evidence, where the best fit lies.

In previous articles, we have dated the biblical patriarchs to the first half of the second millennium b.c.e., with the patriarch Abraham on the scene between the 20th to 18th centuries b.c.e. This dating is based on what is often referred to as an “early Exodus” and “short sojourn” model (see our articles “What Is the Correct Time Frame for the Exodus and Conquest of the Promised Land?” and “When Was the Age of the Patriarchs?”). Without wading into this debate here, others may derive the same general chronological conclusions from the relatively popular “late Exodus” and “long sojourn” model.

Chronologically, this befits the archaeological evidence for what is known as the Middle Bronze ii period (circa 2000–1550 b.c.e.). For example, many of the cities mentioned in the Abrahamic narratives are known archaeologically to have come into existence during the early-to-middle part of this Middle Bronze ii period (cities such as Jerusalem, Hebron, Shechem and Damascus).

Though others following differing chronological schemes have attempted alternative proposals (particularly proponents of an early Exodus-long sojourn model, thus putting events in the late third millennium b.c.e.), we will see that it is squarely within this Middle Bronze ii period—around the 19th to 18th century b.c.e.—that we see a confluence of the full weight of historical data.

First, let’s take a look at the key antagonist: the Elamites.

Elam-Led Juggernaut

“And it came to pass in the days of Amraphel king of Shinar, Arioch king of Ellasar, Chedorlaomer king of Elam, and Tidal king of Goiim, that they made war with Bera king of Sodom, and with Birsha king of Gomorrah, Shinab king of Admah, and Shemeber king of Zeboiim, and the king of Bela …” (Genesis 14:1-2). It is not immediately clear from these verses who led the coalition. One might assume it is the first-listed king, Amraphel. Actually, the names of the rulers are listed here in alphabetical order. It is not until verses 4-5 that the leader of this axis is revealed: “Twelve years they [the Jordan Valley kings] served Chedorlaomer, and in the thirteenth year they rebelled. And in the fourteenth year came Chedorlaomer and the kings that were with him ….”

Chedorlaomer, king of Elam—a distant polity located on the eastern shores of the Persian Gulf in modern-day southern Iran—was clearly the key consolidating player in this account. While the other names are each listed twice, Chedorlaomer’s is mentioned five times in Genesis 14, and the second, non-alphabetical listing of names (verse 9) leads with Chedorlaomer. In two instances in this chapter, the three other kings are described as being “with him.”

This scene, in which a dominant Elam forms an axis with nearby powers, is precisely reflected in history. Historians refer to it as the “Elamite Conquest” period.

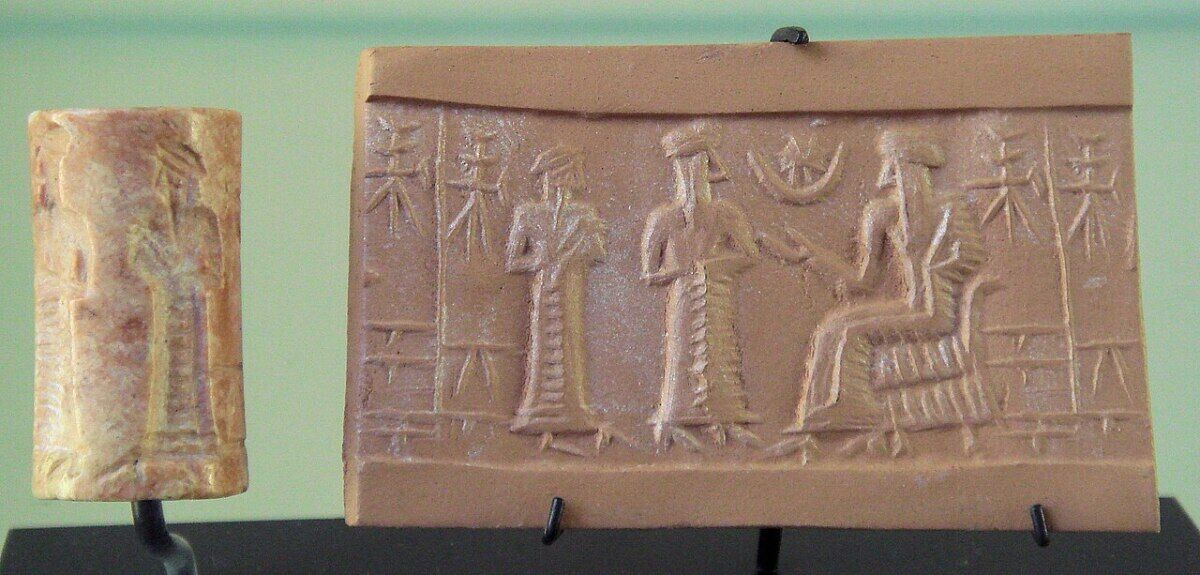

Archaeological evidence shows that around 2000 b.c.e. Elam sacked Ur and effectively ended the dominance of the Sumerian kingdom. Elam was catapulted to new heights of power, primarily during the rich Sukkalmah (“Grand Vizier”) dynasty (beginning circa 1900 b.c.e.). Elam’s diplomatic, commercial and military interests at this time extended as far east as India and as far west as the Levant. Goods from both ends of the spectrum have been discovered at Elam’s capital, Susa, aptly illustrating Genesis 14:4—the flow of Levantine goods to the other side of the Persian Gulf.

“Elam became one of the largest and most powerful of the western Asian kingdoms with extensive diplomatic, commercial and military interests both in Mesopotamia and Syria,” writes historian Trevor Bryce. “Its territories extended north to the Caspian Sea, south to the Persian Gulf, eastwards to the desert regions of Kavir and Lut, and westwards into Mesopotamia” (The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia).

Late Egyptologist Prof. Kenneth Kitchen summarized the Elamite-centric geopolitical reality behind Genesis 14 in his 2006 magnum opus On the Reliability of the Old Testament:

[I]t is only in this particular period (2000–1700 b.c.e.) that the eastern realm of Elam intervened extensively in the politics of Mesopotamia—with its armies—and sent its envoys far west into Syria to Qatna. Never again did Elam follow such wide-reaching policies. So in terms of geopolitics, the eastern alliance in Genesis 14 must be treated seriously as an archaic memory preserved in the existing book of Genesis.

Kitchen adds that “from circa 2000 to 1750 (1650 at the extreme), we have the one and only period during which extensive power alliances were common in Mesopotamia and with its neighbors. Alliances of four or five kings were commonplace and modest then.”

Under this early second-millennium b.c.e. Elamite umbrella, let’s consider the names of the kings in question—starting with the ruler of Elam.

Chedorlaomer, King of Elam

Although the name Chedorlaomer is not (yet) known outside of the biblical account, it does bear the hallmark of an authentic Elamite ruler. The first part of the name, Chedor- (-כדר, the Hebrew of which might be more closely transliterated as Kdur-) corresponds to the well-known Elamite name-element Kudur- (alternately Kutir-). This is a name-element born by several Elamite rulers, including of the Sukkalmah period.

The second part of the name, -laomer, is a perfect match with Lagamar—an underworld deity, whose name means “merciless.” The Hebrew (לעמר-) is an even closer match to this name than the English reveals, bearing within it a Semitic guttural consonant sometimes transliterated as a g, thus alternatively rendering it -lagomer. The third-century b.c.e. Septuagint Greek translation of Chedorlaomer’s name renders it as such: Χοδολλογομορ (Khodollogomor).

Therefore, Chedorlaomer is a perfect representation of the name Kudur-Lagamar—a strikingly apt name for an Elamite ruler, meaning “Servant of Lagamar.”

As far as etymology goes, we have the mark of authenticity. But what about the lack of a known Elamite ruler by this name? To Assyriologist Dr. Stephanie Dalley, this is “not surprising, since there were several concurrent Elamite leaders in that period,” who “are often referred to by their title, ‘grand vizier,’ rather than by name” (The City of Babylon: A History, c. 2000 B.C.–A.D. 116, 2021).

What, then, of the other named rulers? Can they be positively identified?

Arioch, King of Ellasar

The second-listed ruler in Genesis 14:1 is Arioch, king of Ellasar. There is debate regarding this king and his territory. Nevertheless, there is an identically named individual ruling over a similarly named polity that I believe to be the correct fit (an identification that, up until more recent decades, was taken for granted): Eriaku, king of Larsa.

Elam’s subjugation of Ur resulted in more than just the establishment of Elam as a regional superpower; it also allowed the development of the “Isin-Larsa” kingdom. This small kingdom initially began in the city of Isin but was later overthrown and established in the city of Larsa. The Larsa state, located in lower Mesopotamia (modern-day southeastern Iraq), existed for only 150 years, primarily during the 19th century b.c.e. The final ruler of the Larsa kingdom before its collapse was Rim-Sin i.

Rim-Sin was his Akkadian name. His Sumerian name has long been identified as Eriaku—thus in name, period and place, Eriaku of Larsa would be a striking match for Arioch of Ellasar. So striking, in fact, that in early scholarship it was common to equate Rim-Sin i with the biblical Arioch. Examples include Prof. Ira Maurice Price’s 1904 tome Some Literary Remains of Rim Sin (Arioch), King of Larsa and Assyriologist Dr. William Muss-Arnolt’s assessment of this king “whom science is wont to identify with the Arioch (Eri-Aku), king of Ellasar, mentioned in Genesis chapter 14” (“Recent Archaeological Documents,” 1906).

Tidal, King of Goiim

What of Tidal, king of Goiim? Goiim is a Hebrew word simply meaning “nations” or “peoples” (as in many English translations). This individual has long been posited as Hittite, or “proto-Hittite,” due to the linguistic parallel of his name with that of several later Hittite rulers, beginning with the 15th-century b.c.e. Tudhaliya i.

Actually, Tudhaliya i is not the first Anatolian ruler to bear this name. Peake’s Commentary notes, “Certain is the name of Tidal (Hebrew, Tidh’al), which appears in Ugarit as tdghl, [corresponding to the] Hittite Tudkhaliya and Tudkhul’a in the Spartoli texts …. This name is common in the Cappadocian texts of the 19th century b.c.e. and appears frequently among the names of Hittite kings and nobles in later centuries.”

Dalley adds in her 2021 publication: “New evidence for identifying Tidal, long recognized as an abbreviation for the Hittite royal name Tudhaliya, is found on a clay tablet from the pre-Hittite Assyrian merchant colony at Kanesh. He was a ‘chief cupbearer,’ which is a title for a military leader. At that time, Kanesh was conquered by Pithana, king of the unidentified city Kuššara, home to the ancestors of the earliest Hittite kings” (op cit).

Even the rather more obscure territorial title for this biblical Tidal/Tudhaliya is appropriate. Kanesh itself is especially notable as a multicultural, multilingual location—and more generally, the reference to “peoples” or “nations” (Goiim) is befitting of the “fractured nature of political power in Anatolia in the 19th and 18th centuries b.c.e., according to archives of Assyrian merchants in Cappadocia” (Kitchen, “The Patriarchal Age: Myth or History,” 1995; see also Sidebar 1, at the end of this article). Kitchen further noted that the name Tidal/Tudhaliya “is a fair equivalent of the ‘paramount chiefs,’ ruba’um rabium, known in Anatolia in the 20th–19th centuries, or as chief of warrior groups” (On the Reliability of the Old Testament).

We come now to the final ruler of our four-nation axis—the one mentioned first in Genesis 14:1, but whom I have intentionally reserved for last. For it is this individual, I believe, who brings it all together—the key that unlocks the historical picture behind the Genesis 14 account—a king whose identity, in the words of Professor Price, has been “quite definitely determined.”

Amraphel, King of Shinar

The 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia entry for “Amraphel” states: “The identity of the name has long been a subject of controversy among Assyriologists …. [Eberhard] Schrader was the first to suggest that Amraphel was Hammurabi, king of Babylon, the sixth king in the first dynasty of Babylon. This is now the prevailing view among both Assyriologists and Old Testament scholars.” Muss-Arnolt refers to him outright as “Hammurabi, the Amraphel of the Old Testament” (op cit).

Suffice it to say, this is not the case in modern scholarship—academics are much more reticent to directly equivocate historical individuals with their biblical counterparts. Still, the identification of Hammurabi as Amraphel is relatively common and not without reason.

Shinar is well known as cognate with Sumer—the ancient name for Babylon, a polity located at this point in time northwest of Larsa. And as for the name of this king—despite looking somewhat more different in English, it is a similar approximation to the Hebrew name אמרפל, more closely transliterated as ‘Amrapil. Note further that the common spelling Hammurabi is alternately rendered Ammurapi—consonantly, the names are a match, except for the final Hebrew consonant “l.”

Various explanations have been offered for the presence of this final consonant. I believe the following from Assyriologist Marc Van De Mieroop may provide the best answer to this question (though he is not here addressing the subject of Amraphel’s identity):

Hammurabi … was praised in ways that were unusual for kings of his dynasty. Perhaps the highest esteem awarded him was his inclusion among the gods during his lifetime. He is called the god Hammurabi, the good shepherd, in one song …. At the same time people named their children after Hammurabi. The name Hammurabi-ili, meaning ‘Hammurabi is my god,’ appeared, something unparalleled in his dynasty. The references to Hammurabi as a god were probably inspired by a southern tradition, where regularly kings were deified during their lifetime” (King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography).

The above-mentioned song comes from “the former kingdom of Larsa where the scribes still had the habit to write the name of the king with the divine determinative,” writes Rients de Boer. “Hammurabi himself declares in a royal inscription that he put his name in the mouths of the people so that they would proclaim it daily ‘as that of a god’” (“‘Hammurabi-Is-My-God!’: Basilophoric Personal Names and Royal Ideology During the Old Babylonian Period”).

The name Amraphel, then—i.e. Hammurabi-il or Ammurapi-il—may therefore be reflective of the variant “deified” name of this ruler.

The Majesty of Hammurabi

Of all the early kings of Babylon, Hammurabi is arguably the most well-known and consequential. The primary copy of his legal text, the “Code of Hammurabi,” is housed at the Louvre; a replica of it is housed at the United Nations headquarters in New York City. Hammurabi’s portrait adorns the U.S. Capitol building’s House Chamber, right next to that of Moses—one of 23 marble reliefs of prominent law-administrators in history. Hammurabi is known for leading Babylon out of relative obscurity as a minor kingdom to significant heights of power.

He is also the central figure around which early chronology moves. High chronology, which I generally prefer, places Hammurabi’s 42-year reign in the 19th century b.c.e. The more popular middle chronology places his reign in the early 18th century b.c.e. For those keeping track, high chronology is a better fit with the Masoretic chronology of the Hebrew Bible (namely, with respect to the 480 years between the Exodus and building of Solomon’s temple in 1 Kings 6:1); alternatively, the middle chronology is a closer fit to the Septuagint variant (which gives 440 years in 1 Kings 6:1—see here for more detail).

Without bogging down into different schemes, we have different plausible chronological scenarios (i.e. 19th or 18th century b.c.e.) but the same triangulation of three out of our four antagonist kings:

- Amraphel of Shinar as Hammurabi of Sumer/Babylon

- Arioch of Ellasar as Eriaku/Rim-Sin i of Larsa (contemporary with the first half of Hammurabi’s reign)

- Tidal of Goiim/Peoples as Tudhaliya of Kanesh (also contemporary with Hammurabi)

This leaves Chedorlaomer (Kudur-Lagamar) of Elam as the sole unidentified exception; nevertheless, again, this name-type and polity fits neatly within the same time period, during Elam’s Sukkalmah dynasty.

What of the Defendants?

Can anything be said for the other side—Bera of Sodom, Birsha of Gomorrah, Shinab of Admah, Shemeber of Zeboiim and the king of Bela?

Not really. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is far less material evidence for the Jordan Valley-Dead Sea region rulers during the second millennium b.c.e. Archaeologically, we do know of the existence of multiple Jordan Valley cities on the scene during this time; however, we know almost nothing about any of these rulers. To this end, it is telling that even the biblical account itself, while naming each of the kings several times in the account, never identifies the king of Bela by name.

Additionally, when it comes to the names of the leaders of Sodom and Gomorrah—Bera and Birsha—these names seem to exhibit wordplay, something common in the Bible for unsavory characters. In the words of Prof. Ronald Hendel: “The personal names of King Bera (בֶּרַע; bera) of Sodom and King Birsha (בִּרְשַׁע; birsha) of Gomorrah are symbolic—they mean ‘with evil’ (בְּרַע; bera) and ‘with wickedness’ (בְּרֶשַׁע; beresha), revealing their bad moral character” (“Abraham Defeats Chedorlaomer, the Proto-Persian King”).

It is impossible to know whether these names are entirely symbolic or a wordplay on a similar-sounding original name—something apparent with respect to several other biblical figures, such as Nimrod, Cushan-rishathaim, Ishbosheth, Mephibosheth and Jerubbesheth.

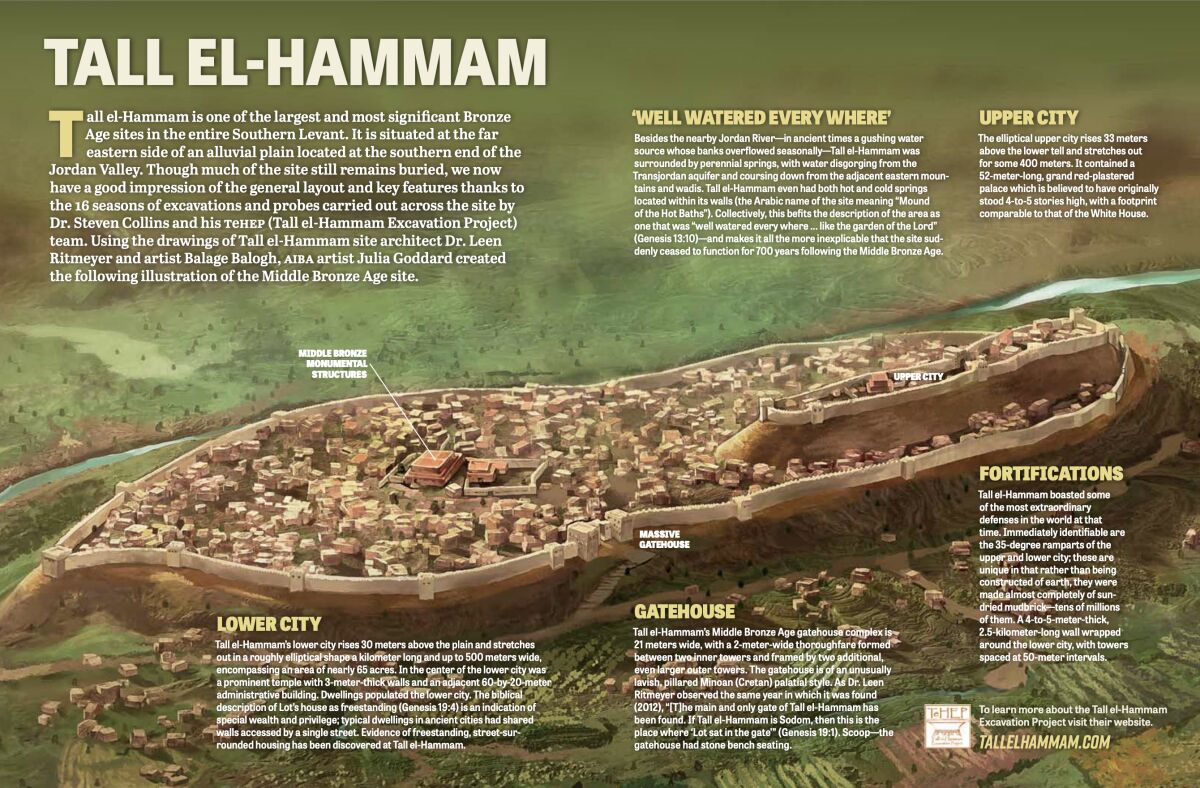

The less-than-flattering naming of these kings is unsurprising, given the following account of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (Genesis 18-19). As an aside, in our broader chronological scheme, this fits well with the destruction of Tell el-Hammam—a key candidate for Sodom, whose demise is dated by the excavators to somewhere between the 18th and 17th centuries b.c.e.

Reconstructing the Historical Landscape

Setting the Jordan Valley kings aside and focusing strictly on the antagonists, and in light of the above information, I would concur with Dalley that the Genesis 14 account best “links with foreign rulers early in the reign of Hammurabi.” This is based on Arioch/Eriaku’s reign overlapping the first part of Hammurabi’s reign and the fact that Amraphel/Hammurabi is a junior partner in the Genesis 14 account (led by Elam).

The early years of Hammurabi’s reign have been described as internally “peaceful” and concentrated on the development of his relatively minor state during a time of Elamite dominance. “Elam was strong and rich, however, and it seems to have been respected and feared by all,” writes Van De Mieroop. “The ruler could intervene in local Babylonian matters, impose his wishes and adjudicate disagreements … the kings [of lower Mesopotamia] seem to have acknowledged the Sukkalmah as a very important ruler whose authority superseded their own. When they quarreled, they hoped for the latter’s support to enforce their claims,” even going so far as to address the Elamite ruler as “father” (op cit).

Rather strikingly, in light of the Genesis 14 account, the Elamite ruler also has the armies of Babylon and Larsa at his beck and call. One order from the Elamite king written to Hammurabi reads: “I have decided to start a campaign …. Mobilize your elite troops.” To which Hammurabi replies: “As you have written to me, my army is ready and available for your attack. The moment you attack, my army will leave to assist you” (arm xxvi/2 no. 362). Similar correspondence was had with Rim-Sin i, ruler of Larsa—remarkably paralleling the Genesis 14 account of the Elamite ruler’s access to the neighboring armies of Shinar and Ellasar.

Some 25 years into Hammurabi’s reign, however, a dramatically different picture to the former time of cooperation “suddenly” emerged. Elam turned on certain of the Mesopotamian city-states, with a plot to pit Rim-Sin’s and Hammurabi’s armies against one another. These kings, instead, united to defeat Elam, an effort that was successful; Hammurabi was frustrated, however, with a lack of contribution from Rim-Sin’s forces and subsequently turned on Larsa, conquering the kingdom and ending Rim-Sin’s dynasty.

What could have caused such a “sudden” collapse of alliances—this turning on one another and complete upheaval of the status quo? Could it have been sparked by reversals of fortune during joint campaigns elsewhere—perhaps of the sort recorded in Genesis 14?

In all this, there is a final coalition in Genesis 14 that we have not yet considered.

Abram and the Amorites

You’d be forgiven for thinking that nothing relating to the patriarch Abram/Abraham has ever been discovered. This common assumption has been popularly spread on social media and even across large mainstream media platforms. The New Yorker, for example, published the following in 2020: “In the long war over how to reconcile the Bible with historical fact, the story of David stands at ground zero. There is no archaeological record of Abraham or Isaac or Jacob. There is no Noah’s ark, nothing from Moses. Joshua did not bring down the walls of Jericho …” (Ruth Margalit, “Built on Sand: In Search of King David’s Lost Empire”—see here for a response to this particularly jarring article).

Something can be said for Abram, though. The 10th-century b.c.e. Karnak inscription of Pharaoh Sheshonq i/Shishak mentions a series of locations in the southern Levant, one of which is named “The Field of Abram.” Though it is impossible to determine from the inscription exactly where this “field” is located, it nevertheless would be a logical fit with the only “field” mentioned multiple times in relation to Abram—that of Mamre, where Abram is stationed at the time of the Genesis 14 account (verse 13).

There’s more: The name Abram has also been found on no less than five separate Babylonian documents dated to the 19th century b.c.e., unearthed in Dilbat (just south of Babylon proper) and first published in 1909. These documents reference a certain individual named Abarama (variously spelled Abamrama or Abamram). “With the loss of mimmation, this would be represented in a consonantal text as אברם,” wrote Prof. John van Seters—precisely the Hebrew spelling of Abram (Abraham in History and Tradition, 1975). While this name apparently belongs to a different individual (based on the different name of his father—see Sidebar 2 for different texts potentially relating to Terah), at a minimum it backs up the biblical use of this name during the period in question.

Of Abram, Genesis 14:13 supplies a key piece of information: “And there came one that had escaped, and told Abram the Hebrew; for he dwelt in the plain of Mamre the Amorite, brother of Eshcol, and brother of Aner: and these were confederate with Abram” (King James Version). The New English Translation describes these Amorites as “allied by treaty with Abram.” (Other verses at least allude to Abram’s association with the Amorites—e.g. Genesis 15:16; Ezekiel 16:3, 45; see here and here for more detail.)

The continuing verses of Genesis 14 describe Abram rallying his expansive workforce of 318 men to pursue the withdrawing armies. An oft-overlooked aspect to this is that Abram was joined in his pursuit by his Amorite “confederates.” This is not only inferred by the particular biblical attention drawn to this alliance but is highlighted explicitly at the end of the chapter (verse 24).

What is interesting in light of all this is the fact that Hammurabi himself was an Amorite—part of what is known as the Amorite First Dynasty of Babylon.

One can’t help but wonder: Is it more than just coincidence that at the end of it all, the only eastern polity that would go on to not only survive but also thrive would be the Amorites—while Elam’s realm crashed and burned? Could it be that in the “defeat of Chedorlaomer and the kings who were with him” (verse 17; New King James Version), Chedorlaomer’s drafted Amorite forces were left comparatively spared by Abram’s own Amorite alliance—returning home to assert themselves as the dominant power in Mesopotamia?

The Rest Is History

Some may consider this to be overtly speculative. Yet despite certain missing details, the level of data that converges around the early part of Hammurabi’s reign has led some scholars to take seriously the notion of a historical backdrop to the Genesis 14 account at this time.

One such scholar is the octogenarian Dr. Dalley, who speaks from rare firsthand experience about the shifting academic perspectives on this biblical account. “Over half a century ago many scholars thought that there were references to Babylonian history in the Hebrew book of Genesis 14:1-16, including the garbled names of kings known from cuneiform texts in the time of Hammurabi,” she writes. “A reaction then arose, dominating the subject and solving the problems by simply rejecting them.

“However, as many more texts became available, particularly those excavated at Mari, a return to the earlier view was suggested by Jean-Marie Durand …. Finds of cuneiform texts at Hazor, Megiddo and Hebron indicate knowledge of Babylonian there” (op cit).

The end result? “The apparent identification of names found in cuneiform texts of Hammurabi’s time, and the episode in Genesis, as already suggested by Durand in 2005, has been strengthened by subsequent research.”

Sidebar 1: Josephus’s ‘Assyrians’

In the main article, the Elamites are emphasized as the key antagonist force (Genesis 14:4-5). The first-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus, however, characterized this alliance as “Assyrian” (Antiquities of the Jews, 1.9-10). Yet the Bible makes no mention of the Assyrians at this juncture; instead, it emphasizes the Elamites.

This biblical picture parallels the historical one at this point in time—one not only of Elamite dominance but also comparative Assyrian weakness (corresponding to its lack of biblical mention). This was during the early part of the Old Assyrian Period (circa 2025–1364 b.c.e.), in which Assur was a relatively minor city-state led by a titular governor, rather than a “king.”

Why, then, did Josephus stylize the antagonist forces as “Assyrian”? Notably, he nowhere mentioned any of the other national terms found in the Bible (e.g. Elam, Shinar, Ellasar). It may be that his generic reference to the antagonists as “Assyrian” reflects a broad-brush Mesopotamian designation for the forces.

Yet there may be at least some substance to Josephus’s identification—specifically, in relation to Tidal “of nations.” Note the above-mentioned military leader Tudhaliya of Kanesh—the site of a well-established Assyrian merchant colony. Josephus called the Genesis 14 antagonists Assyrian “commanders.” At least in the case of Tudhaliya—as a military commander within a key location long linked to Assyria—there may be some substance to Josephus’s identification.

Sidebar 2: Is This Abram’s Father, Terah?

Abram is well-known for his migration from “Ur of the Chaldees” (Hebrew, “Ur-Kasdim”) to Canaan. Less well-known is the fact that his father, Terah, initially led his family on this journey (Genesis 11:31), before stopping partway to settle in Haran. It seems evident that Terah’s family had met with violence in Ur, which claimed the life of one of his sons (verse 28)—something expounded upon in Jewish tradition.

A candidate for this origin city of Ur-Kasdim is Urkeš, along Syria’s northeastern border with Turkey. A number of inscriptions have been found dating to the 19th or 18th century b.c.e. (depending on the chronology followed), relating to a prominent official in this city named Terru. This “man of Urkeš” had fallen out of favor with the general population. His plight is relayed in a series of letters to King Zimri-Lim of Mari—another contemporary with the early part of Hammurabi’s reign. “A couple of times I have had to save myself, escaping death,” Terru wrote to Zimri-Lim, lamenting the public hatred for himself (arm 28 44bis).

Could the beleaguered Terru of Urkeš be one and the same Terah of Ur-Kasdim? For more on the striking parallels, see “Has Abraham’s Father, Terah, Been Discovered?”